Concrete will remain the world’s dominant construction material over biomaterials such as timber as the world transitions to net-zero, claims GCCA chief executive Thomas Guillot.

The second most widely used material on the planet after water, concrete is produced by a massively polluting industry that accounts for around seven per cent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions. For comparison, aviation is responsible for closer to two per cent.

However, Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA) chief executive Guillot argues the focus should be on reducing the carbon footprint of concrete rather than seeking to replace it.

“Concrete is really the backbone of all modern society”

“If you look around us, concrete is really the backbone of all modern society,” he told Dezeen. “So it’s easy to say we get rid of cement, but the reality is that everywhere we look for infrastructure, for schools, for roads, for development, cement is there. The world needs cement.”

“So the question is now: if this material is fundamental to the world, then we are custodians as an industry of that material, and as much as we need concrete, we need us to bring net-zero concrete to the world,” he continued.

“The core of our priority is to bring net-zero concrete to the world in the next decades.”

Many sustainable building campaigners argue that to keep global temperature rises under control, concrete must increasingly be swapped out for carbon-sequestering biomaterials, especially timber.

But Guillot believes that his organisation’s vision for a net-zero concrete product will remain the building material of choice for most construction projects, in favour of timber or direct concrete alternatives like hempcrete.

“There are substitutes of concrete,” said Guillot. “The problem is the volume of the use of the material on the scale that concrete is used around the world. So what material can substitute concrete really?”

“You say some of these technologies are better, fine,” he added. “Put a price on carbon and let the market compete, and then we’ll see what is the most effective material,” he said in reference to the GCCA’s call for widespread market-based carbon pricing.

“I’m taking the bet: concrete has a future in a regulated world that says CO2 has a cost and you need to price it.”

The GCCA describes its mission as helping the concrete and cement industry transition to net-zero by 2050.

Its website features multiple fallacy-versus-fact-style articles pouring doubt on the suitability and sustainability of timber as a construction material while extolling the benefits of concrete.

But Guillot denies that his organisation is anti-wood.

“We are not against any type of materials,” he said. “I am definitely not the one that will start to bitch on wood or things like this, because that’s not the point, that’s not my role, honestly. We want to use our energy in trust-forming our materials, not bitching on others’ materials.”

Instead, he claims, the GCCA is seeking a “fair comparison” between the merits of concrete and timber.

“We need to use all the materials we have, but we need to have a fair understanding and we should be candid in front of the reality of what wood is,” he argued.

“We have an issue with deforestation, right? Try to scale using wood in core elements in line with deforestation, in line with mono types of forestry, biodiversity etcetera, etcetera, just try to map that.”

“We are not here to defend an old industry”

The GCCA’s membership includes huge corporations like HeidelbergCement and Cemex, plus more than 40 national cement associations.

It represents 80 per cent of the world’s cement manufacturing capacity outside of China, as well as some Chinese companies including CNBM, which produces around 500 million tonnes of concrete each year. China alone pumps out more than half the world’s concrete and cement.

The GCCA frequently cites the statistic that three-quarters of the infrastructure that will exist in the world by 2050 has yet to be built.

To enable that to happen, it argues, concrete will be crucial. However, Guillot insists the GCCA is not interested in “protecting the status quo”.

“We are not here to defend an old industry,” he said.

“We are not protecting the status quo. We are defending a tremendous – is it a revolution, an evolution? I don’t know, I can’t qualify it today – but we are defending a tremendous change of our industry.”

“We are habitants of the planet, and we totally understand that we are custodians of that material [concrete] and that we need to change things.”

And he concedes that the world will need to find a way to use less concrete and cement.

“We are not saying that it’s concrete and only concrete; there are things out there that will help, including reducing the quantity of material use,” he said. “I say we have to use that material in a more frugal manner.”

“We have to use concrete in a more frugal manner”

Guillot worked in the industry for 20 years before being appointed to lead the GCCA in 2021.

Last year, the body launched a 2050 net-zero roadmap, in what Guillot claims was a “first for the industrial sector”.

Its vision for net-zero concrete seeks “CO2 optimization at each place of the value chain”, according to Guillot.

That includes using concrete more efficiently with the help of 3D printing in construction and better design, plus more accurate measuring of cement brought to market – which is currently often sold by the bag.

It also involves adopting recipes for cement that use less of the high-carbon base material clinker, with the GCCA supporting research exploring clay cement as an alternative to the standard Portland cement.

“Circularity is also an important element,” added Guillot. “I mean how much you can reuse the concrete itself, the recycling of concrete, the recycling of cement. Some of our members have put on the market some cement which has up to 20 per cent of circular material inside.”

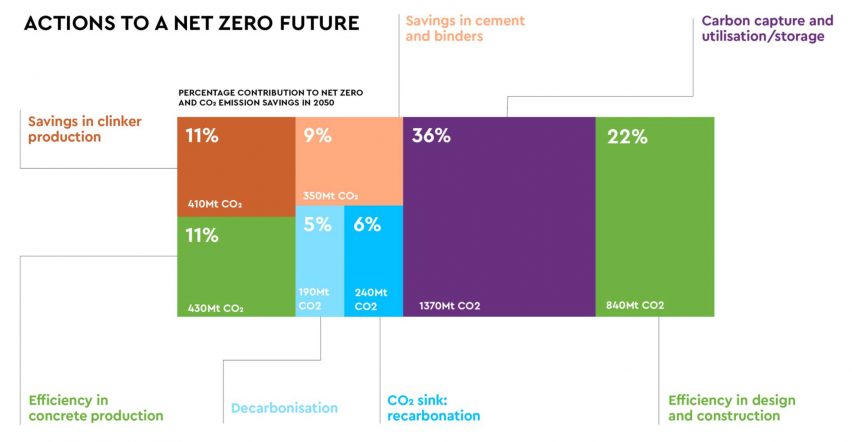

By reducing clinker-related emissions, producing and using concrete more efficiently and transitioning to renewable electricity, the GCCA believes that the concrete industry can cut its total global carbon dioxide emissions – currently 2.5 billion tonnes a year – by 64 per cent.

The remaining 36 per cent, the single biggest element in its net-zero roadmap, relies on carbon capture at cement plants.

“The technology exists, just it is not applied to cement conditions yet”

Industrial carbon capture involves capturing CO2 from factory flues using machines, which can then be stored or utilised for other purposes. At least 35 carbon capture plants are currently planned by GCCA members, though none are yet fully operational.

“All our members are working on that, making the technologies happen, working on innovation to make sure that this is coming,” said Guillot.

“The technology exists, just it is not applied to cement conditions yet, so this is about to be proven,” he claimed.

Some experts believe that carbon capture will form a major part of the world’s transition to net-zero.

Others – including Cambridge University engineering professor Julian Allwood – have argued that the novel materials and carbon capture technologies being explored by industry cannot be scaled up fast enough to decarbonise all of the world’s concrete production by 2050.

The GCCA’s roadmap calls the 2020s “the decade to make it happen” – the period in which it hopes the industry can develop carbon-reducing technologies to roll out between 2030 and 2050.

It had an active presence at the recent COP27 climate summit. One of its main asks is for governments, which represent a large proportion of global demand for cement, to “stop buying high-carbon concrete” according to Guillot.

“You need to create demand for low-carbon material so that these materials can flow, can have its own market,” he said.

Instead of binding targets, which it argues would place firms in some countries at a disadvantage, GCCA members are required to set their own sustainability objectives that increase in ambition year-on-year.

“Judge us on action”

The body’s recently released one-year action and progress report said that the latest available data showed its members had reduced their net CO2 emissions per tonne of cement by 22 per cent between 1990 and 2020.

However, research by the CICERO Center for International Climate Research found that the industry’s overall CO2 emissions have risen dramatically over the same period due to an increase in production.

“Judge us on action,” said Guillot. “We will be relentlessly working on getting people in motion to the transformation.”

“That’s the essence of this association, the GCCA – we need to accelerate the net-zero transition. This is our headache, this is our life motive, and I’m waking up at night saying ‘how do we do that quicker?'”