According to the The International Energy Association, “Heat pumps, powered by low-emissions electricity, are the central technology in the global transition to secure and sustainable heating.” Why? As rooftop solar panels, community solar, and utility-scale renewable energy expand, the incredible efficiency of heat pumps will free us from fossil fuels and help propel the way to zero carbon.

Heat pumps have been around for decades in the form of air conditioners and refrigerators, so the technology is mature and already cost competitive. The Inflation Reduction Act will bring tax credits, 30% off the cost of installation, bringing the technology within reach of even more families and property owners.

And best of all, heat pumps provide better comfort, using a more constant flow of heat compared to the on/off blast of a 3000° natural gas furnace. Heat pumps run smoothly, without temperature swings, and they filter and move more air through the house.

Whole house heat pumps

Similar to a furnace or central AC system, whole house heat pumps pump heat throughout your home via ductwork. For homes with existing ducts, this can be an easy change out of a fossil fuel –burning furnace for a heat pump.

The ducted, whole house heat pumps come in constant speed and variable speed. Constant speed heat pumps (also called single– or dual-stage heat pumps) run at only one or two speeds. They either run at full blast or they’re off, nothing. These often feature a lower upfront cost, but higher operational costs. And they usually require some type of backup (electric-resistance or gas) heating system, because they will struggle to work efficiently below 20° or 30°F. You’ll recognize a constant speed heat pump by the fan on the top of the outdoor unit, looking like a classic air conditioner box.

Variable speed heat pumps run at different speeds, modulating up and down to maintain the target temperature. They run a lot, but at lower energy levels and are overall more efficient. They will cost more upfront, but many work well in much colder temperatures. Thus, all cold climate heat pumps run at variable speeds.

Compared to the on/off blast of constant speed heat pumps, variable speed models run more quietly at lower speeds. You’ll see a more vertical looking outdoor unit with a fan on the side rather than the top. Variable speed units can be used with both ductless and ducted heat pump systems.

In 2021, we replaced an ancient gas furnace on one side of a Cleveland, OH, duplex. This whole-house, variable-speed heat pump provides heating and cooling under highly variable weather conditions. Because it’s used for short-term rentals, we keep it at a comfortable 72° all year. This all-electric arrangement on this side of the duplex costs far less to operate than the gas side.

- Ductless system with variable speed heat pump. Image courtesy Mitsubishi.

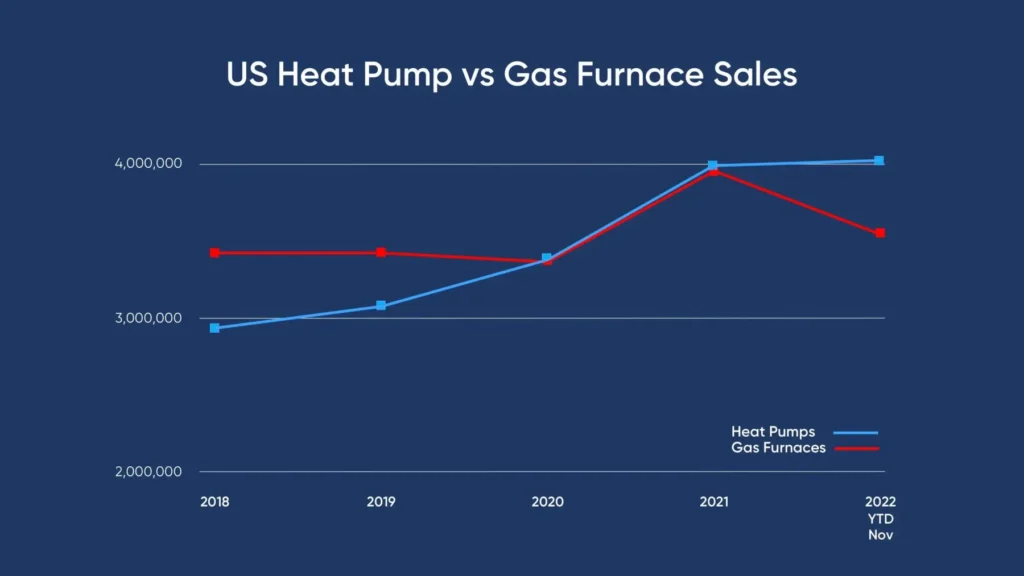

- Source: Air Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute data and Electrify Now.

Ductless heat pumps

As their name implies, ductless heat pumps don’t use ducts to distribute heat. Instead, they rely on indoor units (aka “heads”) installed in the wall, linking directly to an individual outdoor condenser; similar to a window or wall air-conditioning unit. This means that no conditioned air is escaping through leaky ducts, nor are ducts exposed to sunlight or unconditioned space. So ductless installations are most efficient.

Ductless heat pumps are logical for any space without ductwork. And they offer efficiency, economic, and environmental advantages over a central ducted heating system. All DHPs use variable speed technology. One downside is that you need to install a head on an exterior wall wherever you want heat; or provide backup electric-resistance heaters for rooms that don’t (or can’t) have a head

In our home in Portland, OR, heat pumps have kept our family warm for over a decade, since we removed our gas furnace. We also gained some square footage in our garage, which we have converted to an accessory dwelling unit.

The home came with baseboard electric heat in bedrooms and bathrooms, in addition to the central furnace. We now have two heat pump “heads” in the living room and master bedroom, and we use the backup electric-resistance heat very occasionally in the other rooms. This hybrid approach reduced our capital costs and costs us incredibly little to run. Our energy bills are only 20% of the national average!

How will they propel us to zero?

A heat pump uses refrigerant to capture heat and then moves that heat into (heating) or out of (cooling) your house. In the winter they pump heat from outside (even from cold air) to the inside, and in summer, they reverse. Here in Portland, and other places across the globe, climate change is bringing a greater need for cooling. A heat pump is, essentially, a super-efficient, reversible air-conditioner that you can use year-round.

Heating currently accounts for nearly half of all the energy used in homes. For heating, heat pumps are three to five times more efficient than fossil fuels, and save 50% on electric bills compared to electric resistance systems. They will heat everything, from air to water to laundry, and where they’re powered solely by renewable energy, they produce zero operating carbon.

Heat pumps are therefore key to decarbonization. As they are becoming more widely available, more contractors are becoming familiar with how to size, install, and maintain them. Of the 41% of US homes that use electricity for heating, only a quarter of those (13 million) use efficient heat pumps. But in 2021, heat pump sales surpassed gas furnaces, in the US, for the first time.

Whether it’s ducted or ductless, in Oregon or Ohio, modern ranches or old craftsman duplexes, our family has used the mighty heat pump to stay warm, save money, and do our part to solve the climate crisis. So while heat pumps might not get as much love, they rank up there with solar panels and electric vehicles as crucial technologies that will decarbonize our lives without sacrificing modern comforts. Let’s get heat pumped up and put one of these amazing machines in every home ASAP.

This article springs from an post by Naomi Cole and Joe Wachunas, first published in CleanTechnica. Their “Decarbonize Your Life,” series shares their experience, lessons learned, and recommendations for how to reduce household emissions.

The authors: