Shipping and the UN SDGs

In March 2021, the global supply chain faced a crippling blockage. One of the largest vessels in the world, a container ship called the Ever Given, had become lodged in the Suez Canal after struggling through high winds and a dust storm. The resultant disruption to shipping lanes backed up hundreds of cargo ships and laid bare the importance of shipping for the world economy.

Shipping is the overwhelming method of transport for global trade as it is far cheaper than air freight, albeit slower. In fact, the OECD reports that around 90 per cent of traded goods are carried over the waves. And maritime trade volumes are set to triple by 2050.

Sea freight has less of an environmental impact than transporting cargo via aeroplanes. Aeroplanes emit 500 grammes of carbon dioxide per metric tonne of freight per kilometre of transportation, while transport ships emit only 10 to 40 grammes. Nonetheless, shipping faces a key sustainability challenge: its reliance on low-quality petroleum-based bunker fuel. This results in emissions of both CO2 and harmful air pollutants. Add to this the more localised impact of water, acoustic, and oil pollution, and it is clear that change is required in the industry as humanity tackles the existential issues of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Despite the challenges, the shipping industry can play an important role in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. And maritime innovators around the world are showing how this is possible.

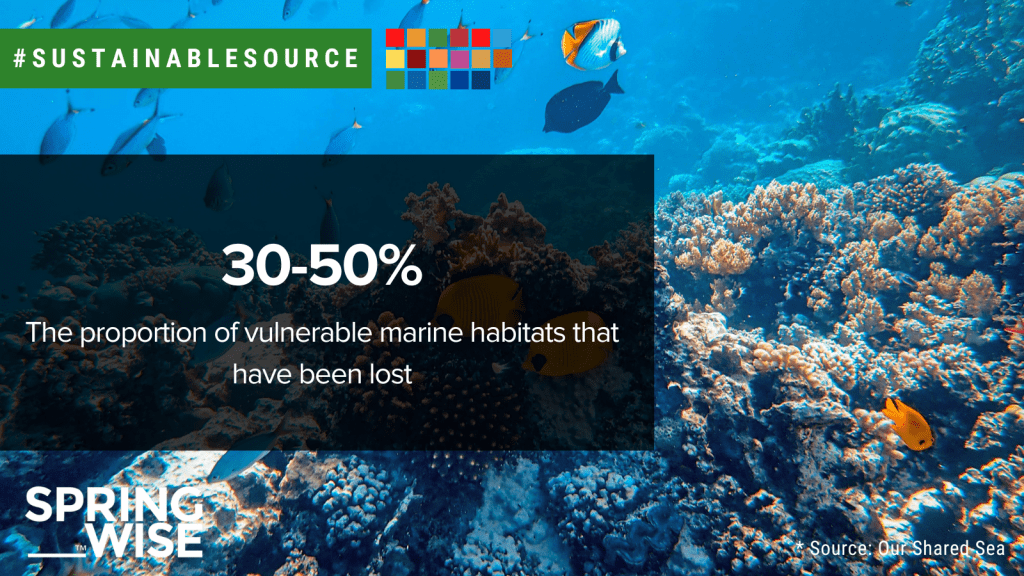

SDG 14 Life under water

The SDG that shipping has the most obvious role to play in delivering is SDG 14, which calls for action to preserve life under water. The marine environment is under threat from a range of human activities from overfishing to the introduction of invasive species. But one key issue is plastic pollution, with an estimated 11 million tonnes of plastic entering the ocean each year.

Ships are responsible for a proportion of marine plastic litter, but the vast majority of ocean plastic actually originates on land. And the shipping industry can play a positive role in tackling the problem. For example, technology group Wärtsilä and shipping company Grimaldi Group, have developed a microplastic filtration system for ships. The new filter makes use of the open-loop scrubber system installed on most ocean-going vessels. Elsewhere, shipping giant Maersk is lending ships to environmental non-profit the Ocean Cleanup. This organisation uses giant floating barriers to tackle the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

SDG 7 Affordable and clean energy

Fossil fuels remain the primary energy source for the shipping industry. In fact, shipping uses four million barrels of oil per day, equivalent to four per cent of global oil production. Decarbonising ship propulsion is a challenge, and the International Chamber of Shipping acknowledges that alternative fuels are not currently available at the scale required for widespread decarbonisation.

Nonetheless, innovators in the industry are busy exploring alternative energy sources. Montreal-based global shipowner The CSL Group, for example, recently completed the world’s longest-running trials of B100 biodiesel on marine engines. And, in terms of the industry’s land-based operations, Ports of Stockholm has announced plans to install hydrogen fuelling stations for its trucking vehicles by 2025. Longer-term, maritime shipping startup Fleetzero is developing smaller, electric-powered ships that use a battery-swapping system to improve efficiency. Hydrogen and ammonia are also being considered as potential fuels for powering shipping vessels.

SDG 8 Decent work and economic growth

The shipping industry is a major source of employment and an important contributor to GDP across the globe. In fact, there are estimated to be 1,647,500 seafarers serving on internationally trading merchant ships.

Innovators are working to maximise the industry’s economic contribution by making it more efficient. For example, predictive intelligence startup Windward is developing technology to better analyse shipping data in order to reduce financial risk on the high seas. And Omani startup Cubex global has developed a blockchain-enabled marketplace to optimise empty cargo space.

SDG 9 Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

SDG 9 calls for innovation to develop quality, reliable, sustainable, and resilient transborder infrastructure to support economic development. In the case of shipping, this comes in the form of solutions that optimise trade routes and technology to streamline the running of ships themselves.

Logistics technology firm Portcast is using AI-powered predictive analysis to save shippers and customers money by shortening trips and reducing emissions. Meanwhile, Dutch maritime company Port Liner is providing us with a glimpse of the future of shipping with all-electric, fully autonomous cargo barges designed for the popular Rotterdam-Antwerp-Duisburg shipping corridor.

SDG 13: Climate action

Shipping accounts for 2.5 per cent of CO2 emissions, so decarbonising maritime trade will be important as countries aim to reach net zero. As discussed above, one of the biggest challenges is weaning the industry of its reliance on fossil fuels as an energy source. But beyond, alternative fuels and batteries, innovators are exploring other ways to reduce the impact of shipping on the climate.

French company Airseas has developed a parafoil sail—known as the Seawing—that is designed to be installed on cargo ships to reduce fuel consumption. The 500-square-metre Seawing is designed to deploy automatically, rising up above the ship’s deck to grab the steady, strong winds at heights of 200 metres above sea level. Elsewhere, US startup Carbon Ridge has developed technology to capture CO2 emissions from ship engines and store them in solid form, preventing them from entering the atmosphere.

Words: Matthew Hempstead

Want to know more about a specific SDG? Why not download our full SDG report published with our partner edie.

In a former armaments factory on the Brooklyn waterfront, Montreal-based stone supplier Ciot has a new home designed by Bando x Seidel Meersseman. The beautiful slab gallery is unrecognizable from its past life, with a bright and meticulous showroom and gallery gaining an air of drama and sophistication under its mono-chromatic refurbishment.

In a former armaments factory on the Brooklyn waterfront, Montreal-based stone supplier Ciot has a new home designed by Bando x Seidel Meersseman. The beautiful slab gallery is unrecognizable from its past life, with a bright and meticulous showroom and gallery gaining an air of drama and sophistication under its mono-chromatic refurbishment.

South 2nd is a surprising addition to an existing single-story American ranch house. The new 900-square-foot building is connected to the current house through an adjacent link and contains home offices on the ground floor and a further bedroom and bathroom suite above.

South 2nd is a surprising addition to an existing single-story American ranch house. The new 900-square-foot building is connected to the current house through an adjacent link and contains home offices on the ground floor and a further bedroom and bathroom suite above.