Net-Zero vs Passive House: What are the Similarities and Differences?

Have you ever wondered what the difference is between a net-zero house and a passive house? They’re both buzzwords in the green industry. But also appear in the mainstream news and the speeches of politicians. Gaining in popularity, it’s good to be aware of the differences. In some cases, it’s the smallest of details. But these different approaches to building can have a big effect on cost, comfort, true sustainability, environmental savings, and much more. We’ll explain the differences so that you can make an informed decision on which type of green building to pursue when designing or renovating your own home. We’ll also share how our family approached our first net-zero solar home renovation project, and how we kept costs to a minimum.

What is a Net-Zero Energy Home?

A net-zero home produces as much energy on an annual basis as it consumes. Design and engineering usually involve off-the-shelf energy-efficient technology and renewable energy sources, such as solar panels, to reach zero net energy use throughout the year. It may not necessarily be completely engineered to use the lowest energy possible, but if it produces enough to make up for those shortcomings, it could be considered net-zero.

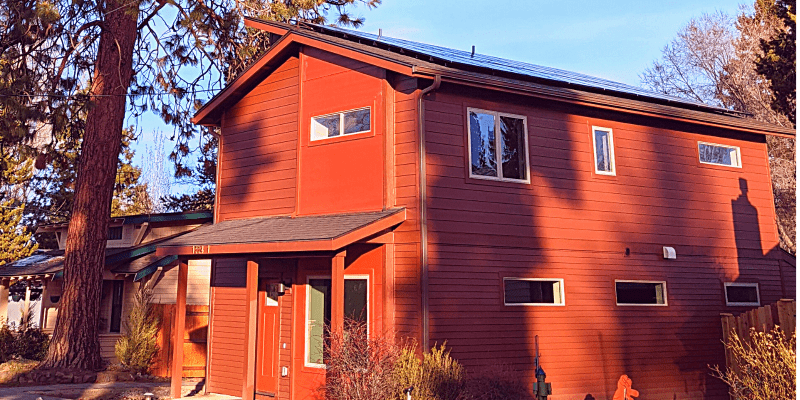

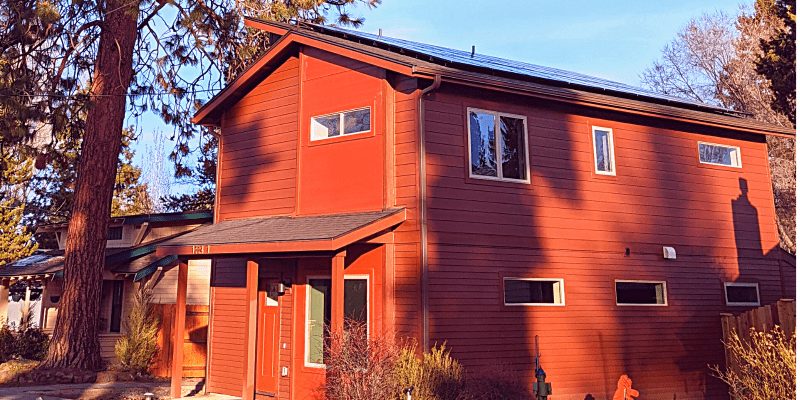

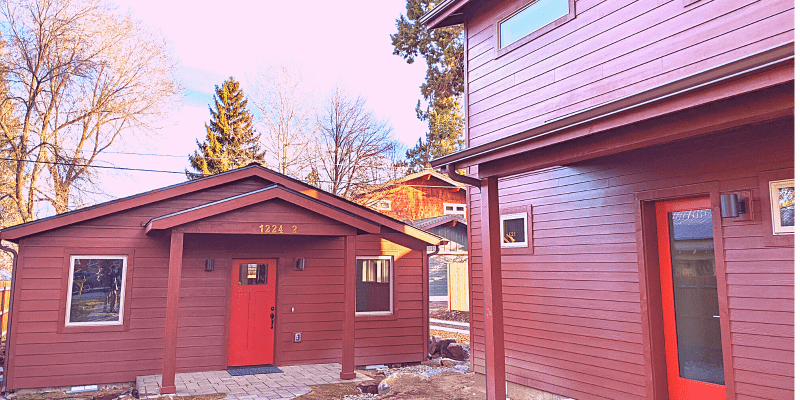

Our own affordable net-zero home renovation project in Cape Coral, FL.

Our own affordable net-zero home renovation project in Cape Coral, FL.

(See more at Our First Net-Zero Solar Home Renovation (And How We Did It) – Attainable Home)

What Is a Passive House?

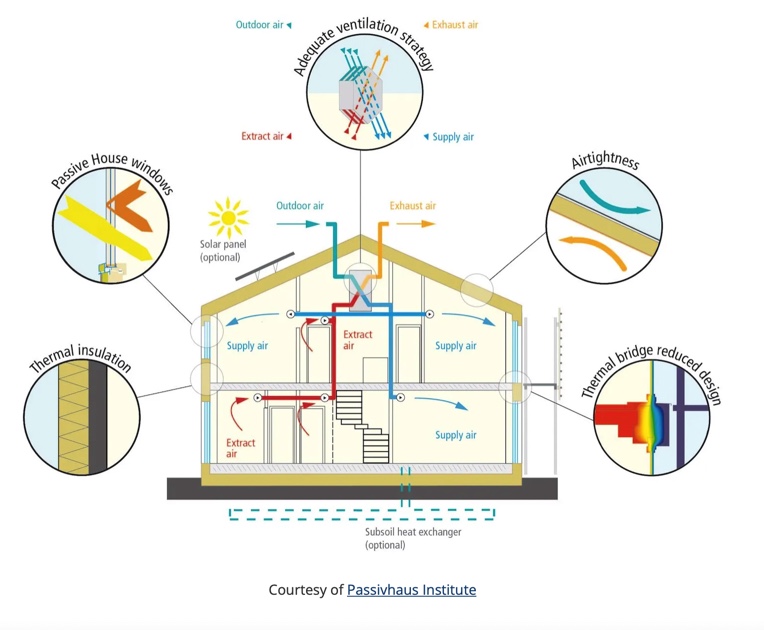

You’ll find many definitions on the web. But most agree that a passive house has highly engineered energy efficiency and stringent design standards while using environmental factors, such as passive solar, to keep energy use as low as possible. It’s a voluntary standard to achieve comfort, affordability and the lowest ongoing environmental impact possible. Here’s how the Passive House Institute defines a passive house: “Passive building comprises a set of design principles used to attain a quantifiable and rigorous level of energy efficiency within a specific quantifiable comfort level.” Another way to describe it is that it “optimizes gains and losses” based on climate. You can learn more at Passive House U.S.

What Similarities Do These Homes Share?

The good news is both are extremely more energy-efficient and sustainable than an average house. And it doesn’t even have to cost that much more either.

Passive houses and net-zero homes share much in common. Both types of homes aim to make sure that their energy consumption is as close to zero as possible.

There are many differences in how they accomplish this, but for the most part, both passive and net-zero houses follow similar principles.

Common Characteristics of Both Net-Zero and Passive Homes:

None of these are requirements, but all energy-efficient homes, regardless of the label, usually aim to have most or all of these characteristics:

- The building envelope is as air-tight as possible within budget. If you can control the air inside and prevent air leakage, the mechanical systems run less.

- Elimination of thermal bridging when possible. A thermal bridge is a component in the house that acts as a thermal conductor between the inside and outside of the house, such as window and door frames.

- High-performance energy-efficient windows.

- Thick and continuous insulation through the entire building envelope. Insulation acts like a blanket around your house (similar to your to-go coffee mug that keeps your coffee warm for longer).

- Mechanical ventilation that keeps air healthy and fresh. Because your building envelope is so tight, the air inside your home has nowhere to go. You must move that stale indoor out and bring fresh air in from the outside while retaining the heat using an energy recovery ventilation system.

- Efficient mechanical systems and appliances. Things like HVAC, your hot water heater, washer, dryer, refrigerator, stove, dishwasher, and others must be energy efficient. But perhaps more importantly – they must be designed correctly for the home. If systems are too big or small for their actual workload, they can work overtime and burn out.

- Some use of shading. Ideally, you have shading on the roof that is optimized to let the warm sun in through the winter (when the sun is lower in the sky) and shade for the windows in the summertime.

- Renewable energy. Even with energy-efficiency measures and stringent passive house standards, you may still need to generate some power to get to net-zero. This is where solar energy, small wind turbines, geothermal, or perhaps small micro hydropower might come in. We did a whole article on solar alternatives if you’re interested in learning more about that.

The major difference between passive and net-zero homes is that Passive House’s stringent standards for insulation, air sealing, and use of passive solar reduce the energy needs of the building to the point that very little solar may be needed to get to net zero. On the other hand, net-zero homes have less stringent standards and may require more solar to get to zero.

How Much Do These Energy Efficient Homes Cost?

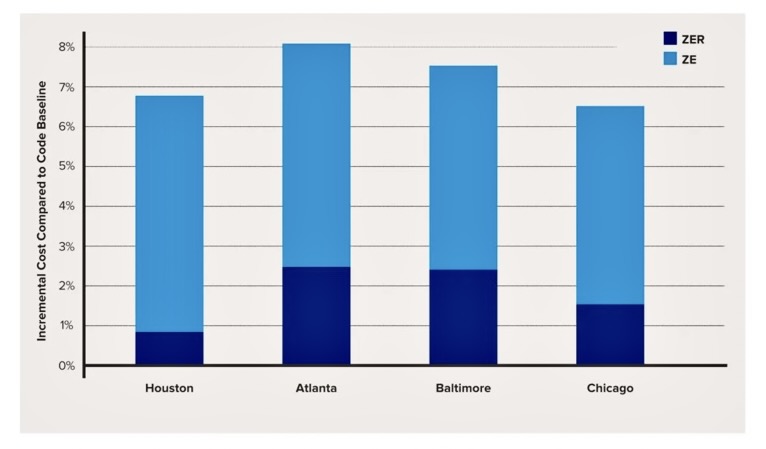

Many factors contribute to the total cost, so it’s hard to say exactly. The best graph we’ve found appears in Rocky Mountain Institute’s 2019 report, “The Economics of Zero-Energy Homes,” which shows that net-zero homes only cost about 6-8% more than traditional homes.*

Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain Institute study entitled The Economics of Zero-Energy Homes

Similarly, according to the Passive House Institute US, a passive house typically costs 5-10% more than a typical home. For the net-zero home renovation we did (see below), the efficiency measures and solar energy costs equate to 6.8% of the final appraised home value, so nearly dead-on with RMI’s findings.

A Case Study – Our Attempt at a Net-Zero Home Renovation

I wanted to create the most affordable net-zero home renovation I could muster. The goals were clear and deliberate:

- Keep the total cost under the median average home price of the area.

- Ensure that it could rent for 10-15% above all ownership costs, including long-term maintenance. This is because things change in life and I wouldn’t be forced to sell in a down-market.

I was aware of the Passive House concept before starting, but my goal was to get to net-zero as affordably as possible. The reality is, unless you’re building from the ground up, a Passive House design is difficult to implement because most existing homes would require extensive renovation to meet Passive House standards.

My approach was to use energy and financial models to go after the lowest hanging fruit. This created the freedom to let the spreadsheets tell me what to do on the project. This is house-specific, so each project is different.

Going After The Lowest Hanging Fruit – A Surprising Example

The house had a 2007 13 SEER HVAC system. Naturally, I thought that I must replace it to achieve net-zero. As it turned out, while doing the energy and financial modeling, that wasn’t the case. In my location, at least on this house, with my electric rates, and a Florida climate, adding more solar panels on the house cost less than upgrading to a new higher SEER HVAC system. By going after the cheapest and most effective energy-saving measures possible, the overall project was a success and not as big a hit on the wallet. With this approach – even with this being my first renovation ever – the total efficiency and solar energy costs equated to 6.8% of the final appraised home value, in line with the studies mentioned above.

Power for the Electric Car, Too

As a bonus, the 9.38KW solar system could, in addition to powering my home, produce enough power to drive a Tesla Model 3 for 10,000 miles per year. At the rate that my current system is producing, it is turning out to be more like 12-14,000 miles per year.

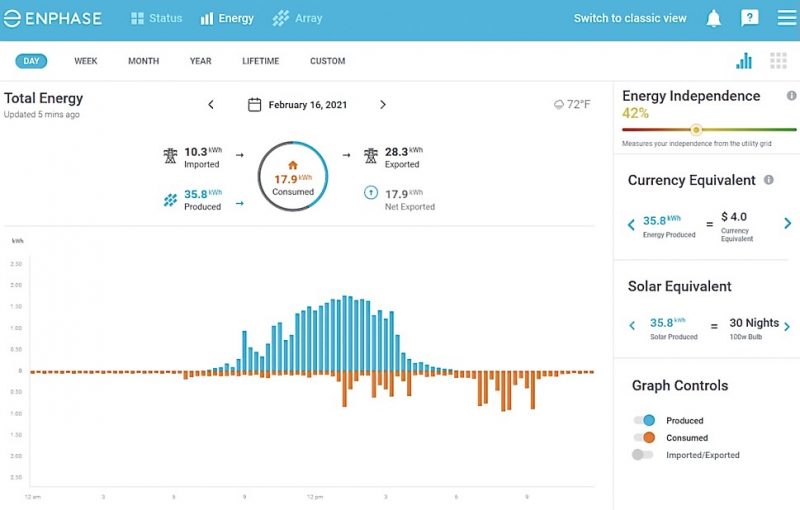

Here’s a picture from our Enphase Enlighten app, showing solar production in blue and home usage in orange throughout

the day.

Conclusion

Although there are differences between Passive House and net-zero home standards, the end goal is nearly the same – to use as little energy as possible on a net basis.

The exciting thing is that these approaches are growing so much in popularity and have world governments behind the concept to boot. The technology is getting cheaper, the building science is getting better, and the overall economic picture makes it much more affordable to build or renovate homes more efficiently on a grand scale.

While there are so many variables with all of this, just know that there are plenty of ways to meet the goals of using less energy, reducing carbon, and building more efficiently, whether it be a passive house, net-zero, or any other way you are able to get there.

Founder | Attainable Home

Original Article Posted on AttainableHome.com

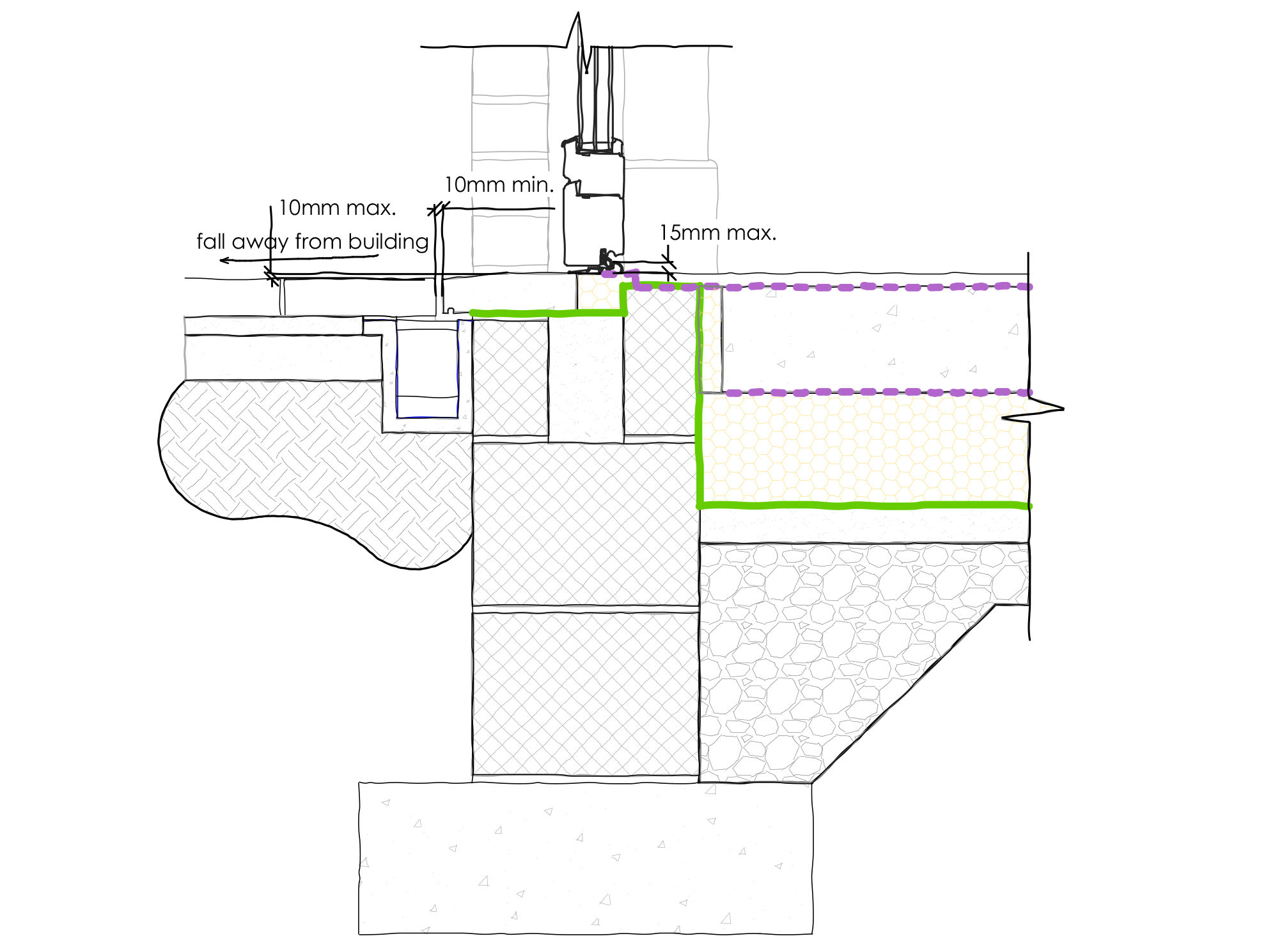

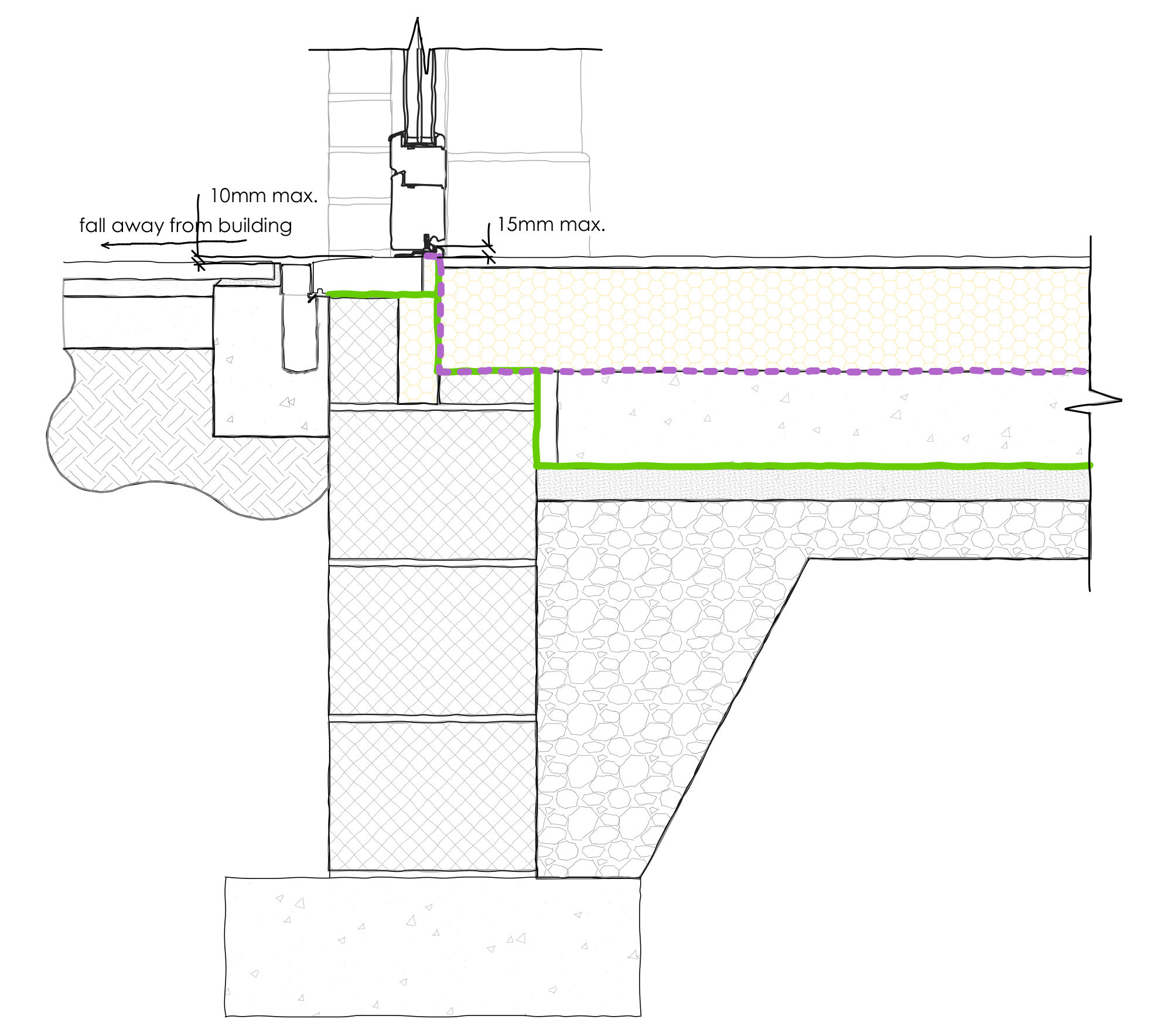

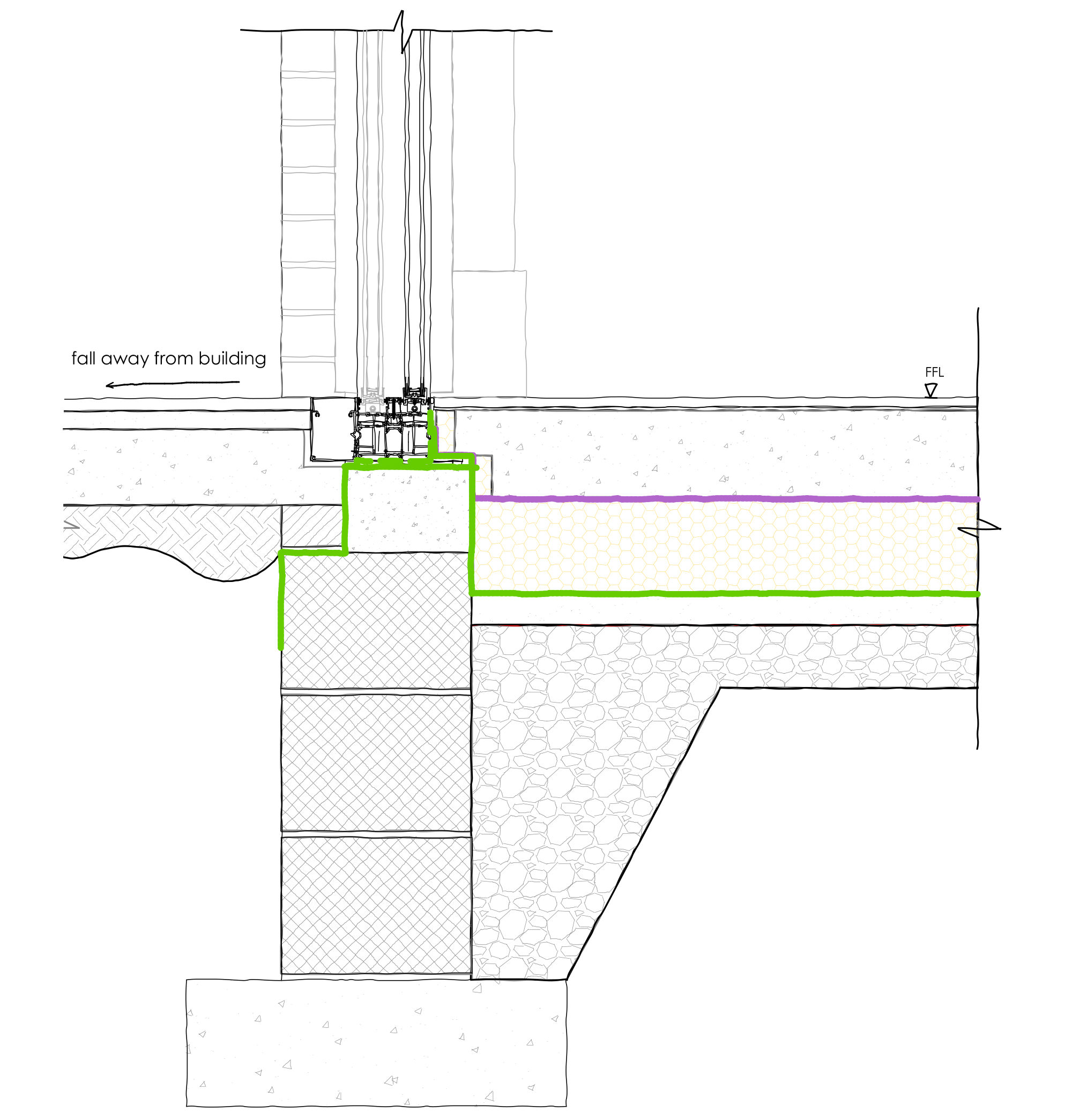

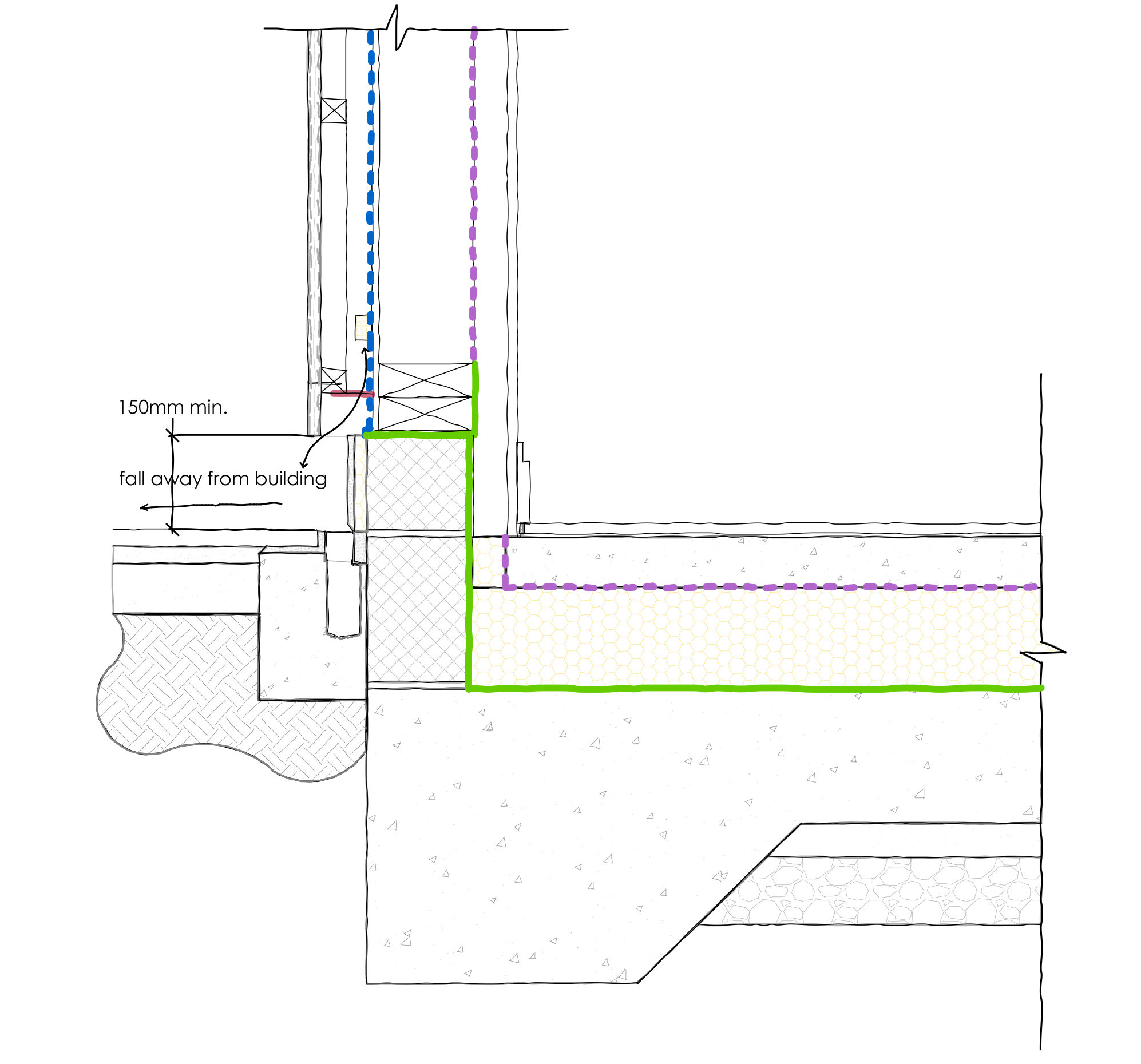

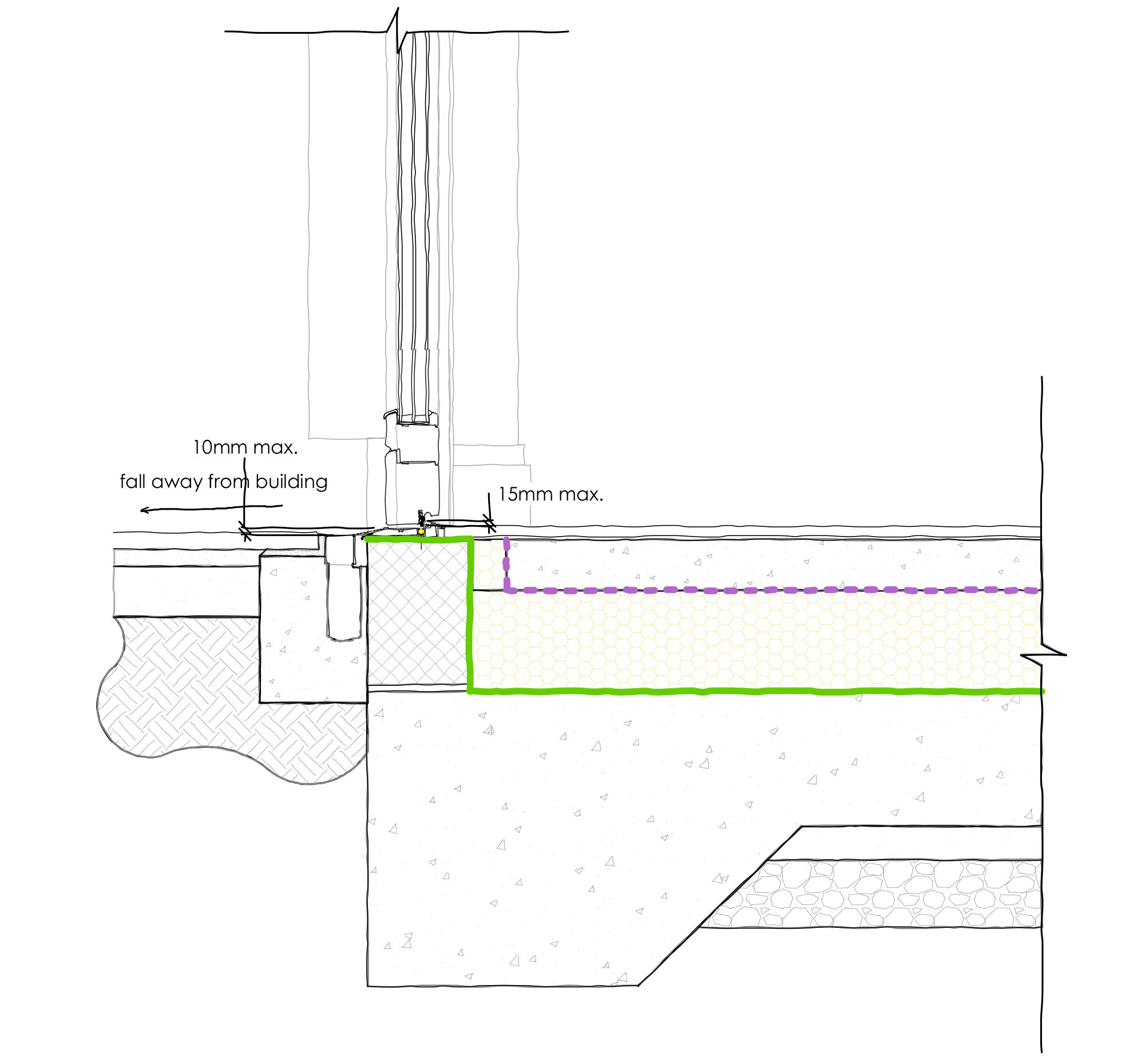

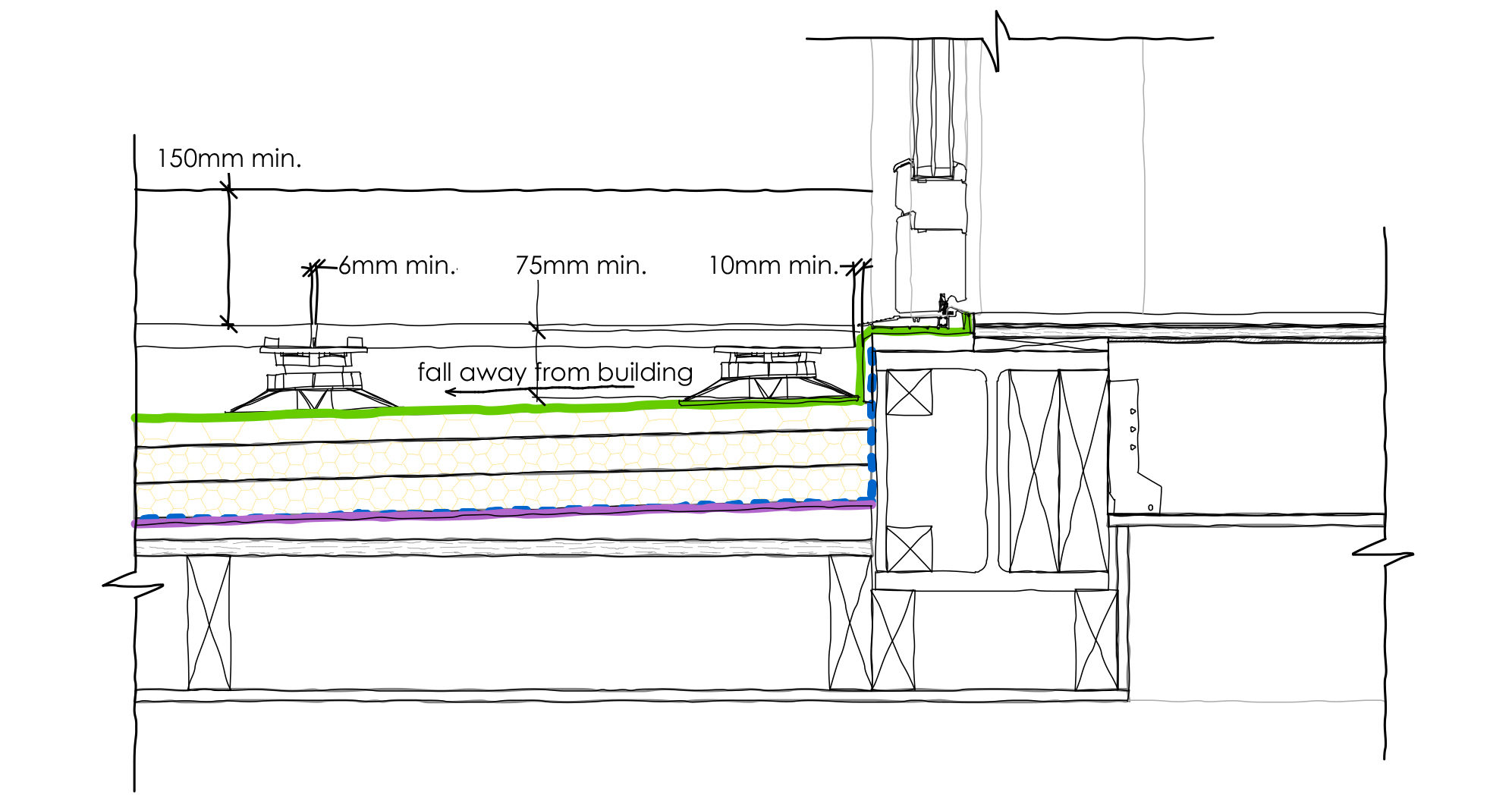

When designing a level threshold onto a raised terrace or balcony, even more care needs to be taken to assure that water does not enter the building fabric.

When designing a level threshold onto a raised terrace or balcony, even more care needs to be taken to assure that water does not enter the building fabric.