MoMA exhibition examines history of environmental architecture

The Museum of Modern Art in New York has opened an exhibition focused on the relationship between environmentalism and architecture in the 20th century.

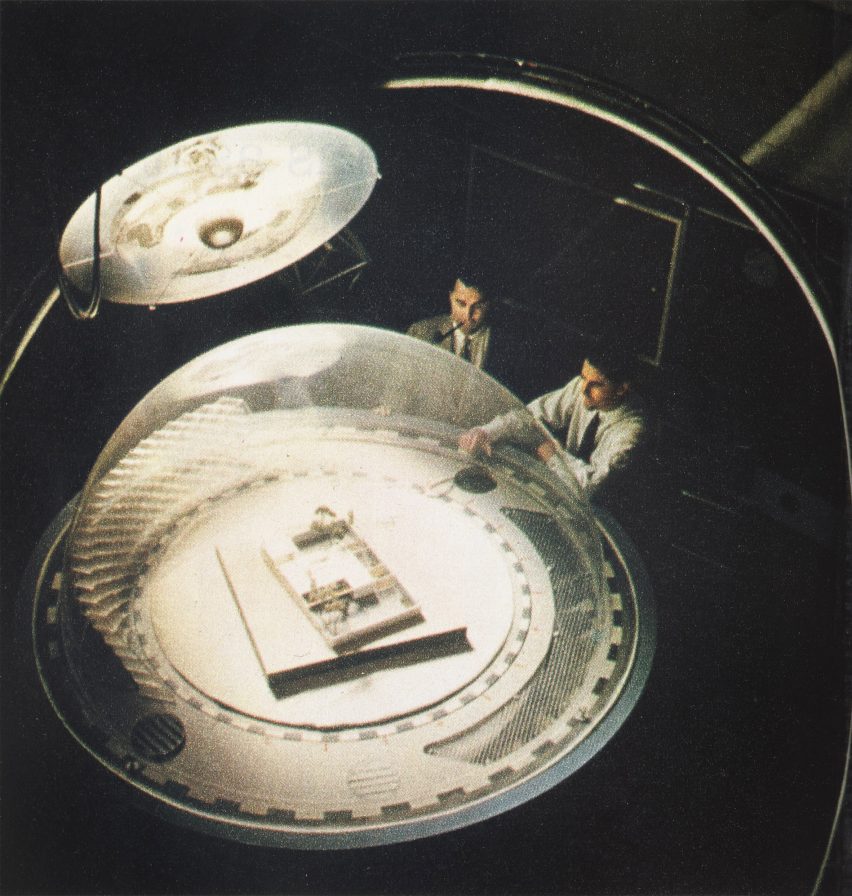

The exhibition, called Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, details work – built and conceptual – produced during the 20th century and features a number of drawings, photographs, models and interactive elements.

Organised by the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) recently established Ambasz Institute, it is was created to expose the public to strains of thinking, including some that are relatively unknown to the broad public.

“The aim is to have, for the first time in a major museum, a platform where the fraught relationship between architecture and environment can really be discussed and researched and communicated to a wider public,” exhibition curator and Ambasz Institute director Carson Chan told Dezeen.

The show is largely historical, focusing mainly on the work done in the 1960s and ’70s, when environmentalist themes were being exposed to the general public on a massive scale, evidenced by the popularity of ideas like those in Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring.

However, precursors to that moment, such as work by early twentieth-century modern architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, with his organic architecture, and Richard Neutra’s “climate-sensitive architecture”, were also included.

Chan told Dezeen that this historical focus was presented to orient contemporary audiences to the roots of current movements.

“A lot of ideas have changed from that moment, half a century ago,” he said. “The show is looking at how far we’ve come from that moment, but also look at what we can learn from that moment to trying to understand where people were coming from, why they kind of the ambitions they had, why they wanted to do things, the things they wanted to do,” he continued.

“Assessing that moment is a big part of the show.”

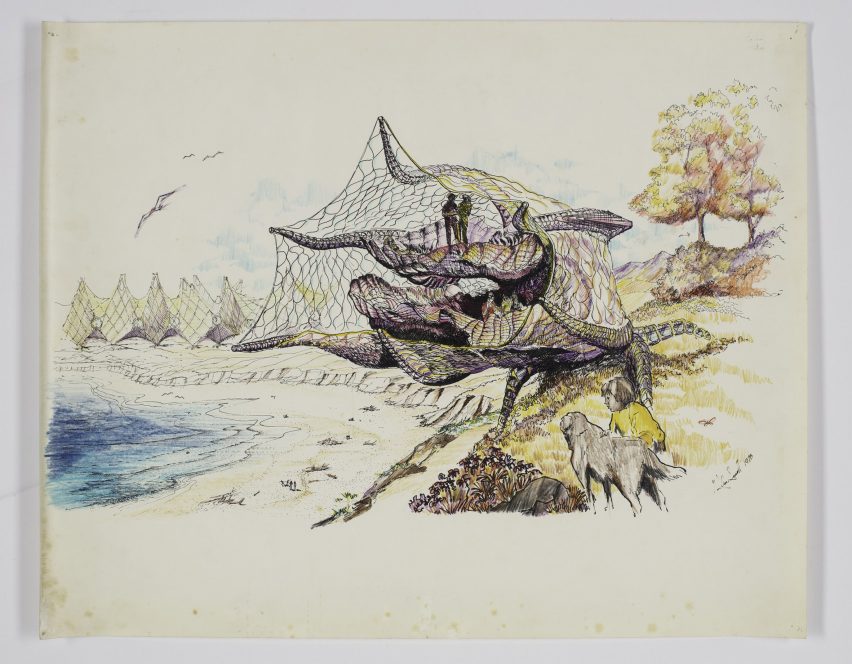

The works include a number of highly conceptual architectural projects such as American architect Buckminster Fuller’s proposed dome over Manhattan, Glen Small‘s sci-fi-inflected Biomorphic Biospheres and Malcolm Wells‘s underground architecture. The paintings of contemporary architect Eugene Tsuii also demonstrated biomorphic forms.

These works imagined radical infrastructures that accounted for changing environments and growing populations

The exhibition also included built work including Michael Reynolds‘s waste-built Earthships and the New Alchemy Institute‘s self-sufficient ark buildings, as well as the tree-covered works of Argentine architect Emilio Ambasz, after whom the MoMA’s aforementioned institute was named.

There were also works of radical cartography that served to show the complexity of the landscape. These included American academic Ian McHarg’s detailed ecological maps of the Delaware Upper Estuary, which showed data-driven layers of ecological features such as soil conditions and sun conditions.

However, Chan was careful to note that these understandings of environments predated the environmental movement.

“Doing research or producing knowledge about the environment – or as I call it, producing ecological knowledge about the environment – did not start in the ’60s and ’70s,” he said. “There are communities of Indigenous people that have been tending to the land for generations.”

“The Delaware River Basin is the ancestral homeland of the Lenape people who possessed this very knowledge already. And we could have received it from them if they weren’t displaced in the first place,” he continued.

“Making structures requires money and requires people to be proximate to power. And so this is one reason why historically we haven’t seen a lot of structures by people of color, and by women.”

The inclusion of these groups mainly focused on activism. For example, a protest against a proposed dam on ancestral land by the Yavapai people showed how the stoppage of landscape-altering super projects is in itself a kind of architecture.

“Subtracting is also a way of making architecture,” said Chan.

In addition to the images and models in the exhibition, the curators also included a number of small audio devices that included commentary from contemporary architects and designers such as Jeanne Gang and Mai-Ling Lokko, aimed at contextualising the historical work.

The Ambasz Institute was created to promote environmentalism in the architectural field and besides exhibitions, it will also carry out a number of community outreach projects and conferences.

Other exhibitions that examine architectural history include an exhibition showcasing the history and work of Vkhutemas, a Soviet avant-garde school of architecture at the Cooper Union in New York City.

The main image is of Cambridge Seven Associates’ Tsuruhama Rain Forest Pavilion, courtesy of MoMA.

Emerging Ecologies is on show at MoMA from 17 September 2023 to 20 January 2024. For more exhibitions, events and talks in architecture and design, visit the Dezeen Events Guide.