Atomic Architecture: Nanotechnology and Building Sciences

Send us a photo. Tell us a story. Win $2,500! Architizer’s 3rd Annual One Photo Challenge is underway with a Main Entry Deadline on June 24, 2022! Start your entry for architecture’s biggest photography competition here.

Architecture is designed across scales and mirrors developments in science and research. Investigating matter on atomic, molecular and supramolecular scales, the field of nanotechnology has now started informing architectural design. In turn, structures for building sciences and research have rapidly expanded. As architects and designers are taking on this typology in public and private sectors alike, the study and evolution of nanotechnology mirror broader developments in how sciences are flourishing.

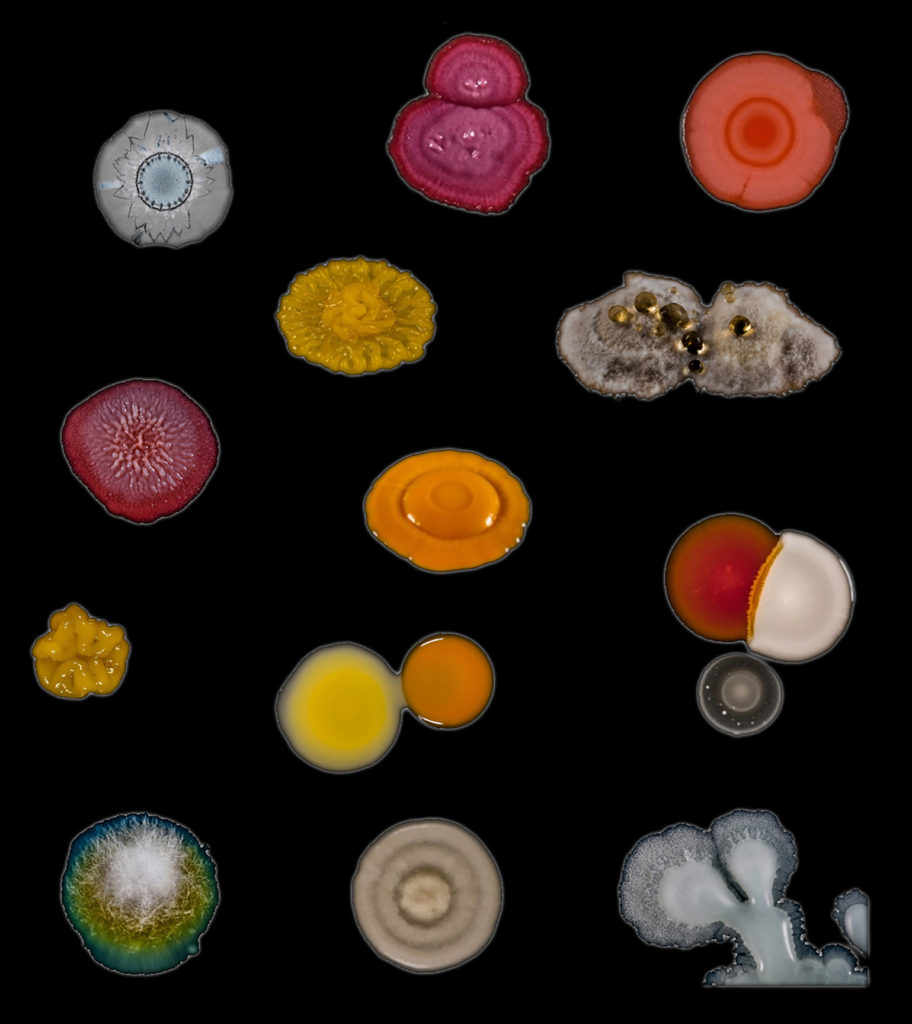

Combining science, engineering, and technology conducted at the nanoscale, the field focuses on a scale of 1 to 100 nanometers. At such a small scale, nanomaterials, begin to exhibit unique properties that affect physical, chemical and biological behavior. By manipulating matter, nanotechnology can create new structures, materials, and devices. Taking a closer survey into the design of structures and buildings for nanotechnology and research, the following collection of projects explores what atomic architecture looks like today.

Krishna P. Singh Center for Nanotechnology by WEISS/MANFREDI, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Krishna P. Singh Center for Nanotechnology by WEISS/MANFREDI, Philadelphia, PA, United States

As the university’s first cross disciplinary building, this nanotech research facility was designed to encourage the collaboration, exchange and integration of knowledge that is the core of this emerging field. The facilities will combine the resources of both the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the School of Arts and Sciences.

Defined by a new central campus green, the building ascends as a spiral of research, reaching its highest elevation at the forum, a meeting space that cantilevers over the quad and opens to views of both the city and campus. A new multi-level crossroads, the center is a significant step toward signaling the University’s leadership in the emerging field of nanotechnology.

National Nanotechnology Park by Arch International Pvt Ltd., Homagama, Sri Lanka

National Nanotechnology Park by Arch International Pvt Ltd., Homagama, Sri Lanka

The Nanotechnology Center of Excellence forms the epicenter of a National Nanotechnology Park that is a result of SLINTEC’s aims to create an ideal space for ‘thinking’. The campus will be a key feature within the ‘knowledge hub’ development plan in Homagama, creating a unique opportunity to house research, incubation and technology commercialization in an area that aims to draw both the public and private sectors.

Elements of all scales and sizes within the architectural language have been used in order to depict the relationship with nanotechnology as well as geometries that are closely involved in the sciences.

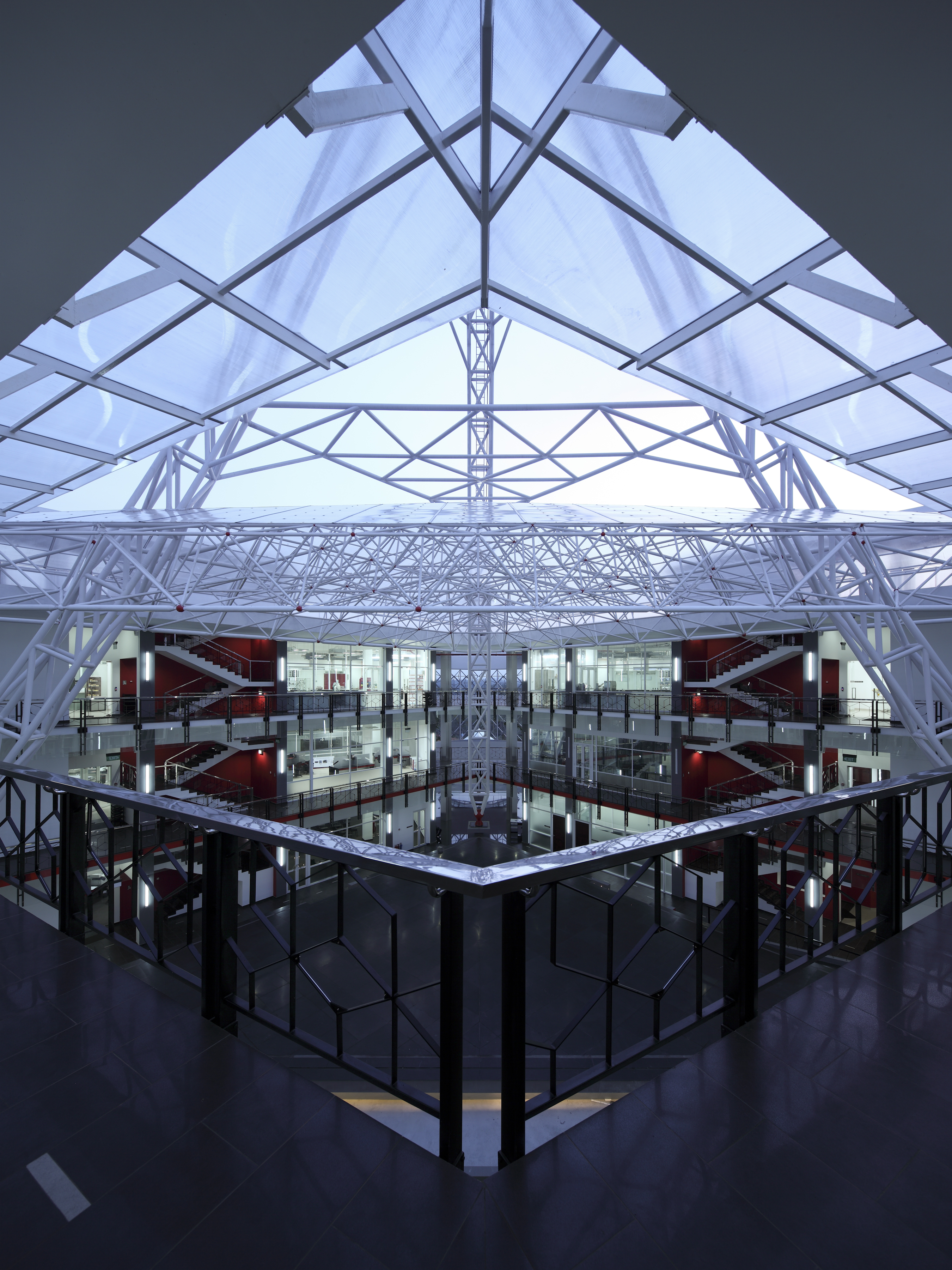

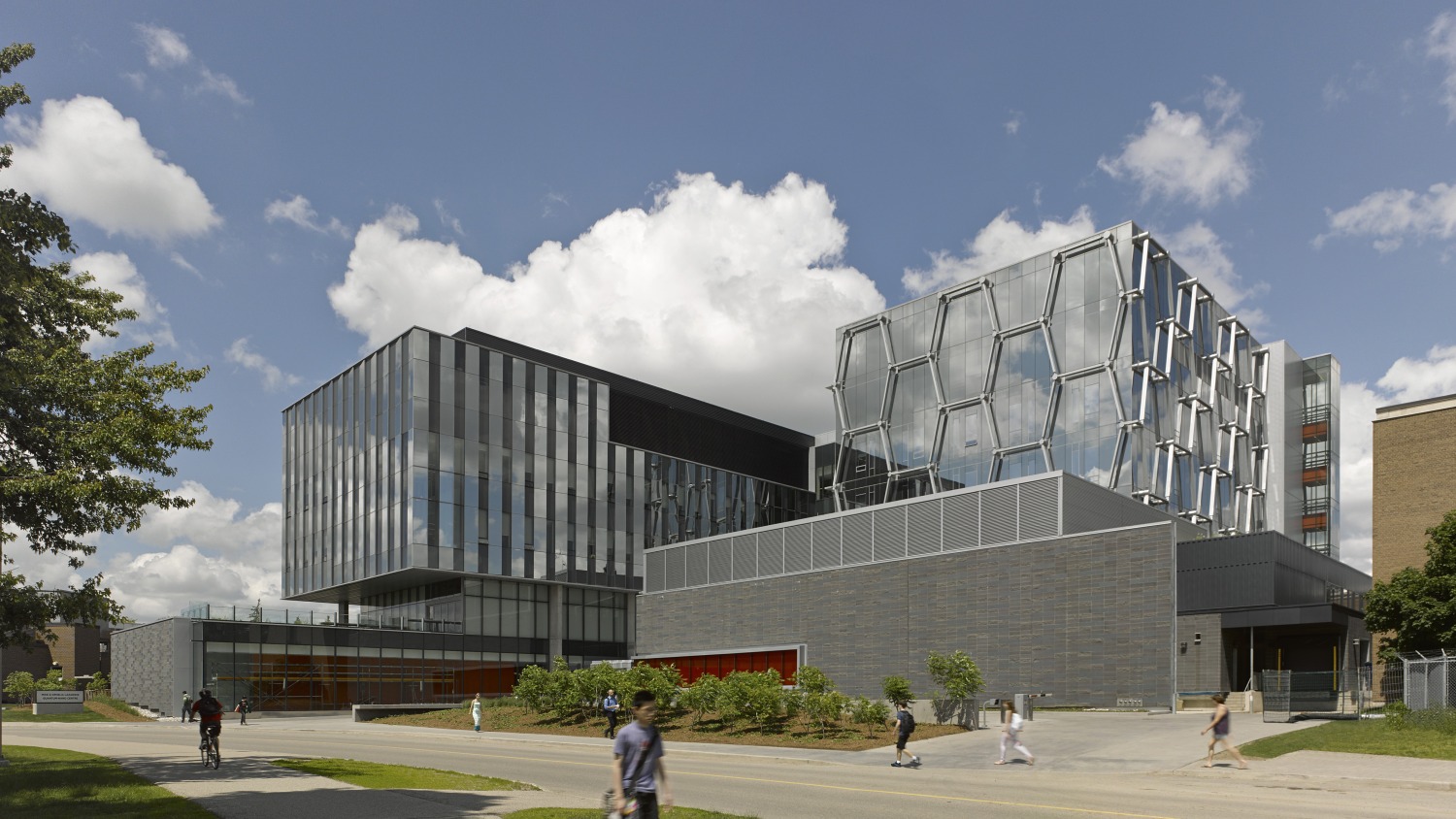

Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano Centre by KPMB Architects, Waterloo, Canada

Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano Centre by KPMB Architects, Waterloo, Canada

The Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano is a showcase for Canadian innovation and industry in the fields of quantum computing and nanotechnology. The social components of the facility in the form of atria, mind spaces and collaborative areas manifest the original goals to attract and inspire the brightest minds in the world. At the official opening, Stephen Hawking, world-renowned physicist and partner with the University of Waterloo since 1999, described the design as a work of “architectural genius”.

New Center for Manufacturing Innovation by Brooks + Scarpa Architects, Monterrey, Mexico

New Center for Manufacturing Innovation by Brooks + Scarpa Architects, Monterrey, Mexico

Located in Mexico’s Research Park for Technical Innovation (PIIT), a science and technology park, which is a partnership between government, universities and the private sector to seek economic growth through technical innovation. The sprawling campus is host to more than 50 research centers devoted to R&D as well as the development of technology innovation in nanotechnology, biotechnology, mechatronics and advanced manufacturing, information technology, clean energy and advanced materials development. The iconic saw-toothed roof is inspired by the geometry of old factories and the surrounding Monterrey Mountains.

Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation by EDGE Studio, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation by EDGE Studio, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

The University of Pittsburgh decided to expand and renovate Benedum Hall, the circa 1968 home for the Swanson School of Engineering on their main Oakland campus. The original limestone clad modernist tower and separate auditorium buildings, with their inflexible and non-daylit concrete block labs and offices and out of date classrooms, had become obsolete as the school’s focus shifted to the 21st century collaborative disciplines of nanotechnology, bioengineering and materials research. The University desired a more flexible facility that was conducive to inter-departmental collaboration, and that could help attract the best and brightest research faculty and students from around the world.

La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science by Lyons, Melbourne, Australia

La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science by Lyons, Melbourne, Australia

This new research centre is a world-class facility for molecular science, biotechnology and nanotechnology research, teaching and learning. The 6 story facility provides approximately 11000m² of learning space – both wet and dry labs – on the lower 3 levels, and 18 research labs on the upper floors. It contains research groups in life sciences (biochemistry and genetics), physical sciences (chemistry and physics), and applied sciences (pharmacy) and teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in these areas through the School of Molecular Sciences.

Send us a photo. Tell us a story. Win $2,500! Architizer’s 3rd Annual One Photo Challenge is underway with a Main Entry Deadline on June 24, 2022! Start your entry for architecture’s biggest photography competition here.

Villa Vals by SeARCH, Vals, Switzerland

Villa Vals by SeARCH, Vals, Switzerland

Khyber Ridge by Studio NMinusOne, Whistler, Canada

Khyber Ridge by Studio NMinusOne, Whistler, Canada

House D by PAUHOF Architekten, Austria

House D by PAUHOF Architekten, Austria

Sheltered Villas by A&M Architects, Karpathos, Greece

Sheltered Villas by A&M Architects, Karpathos, Greece

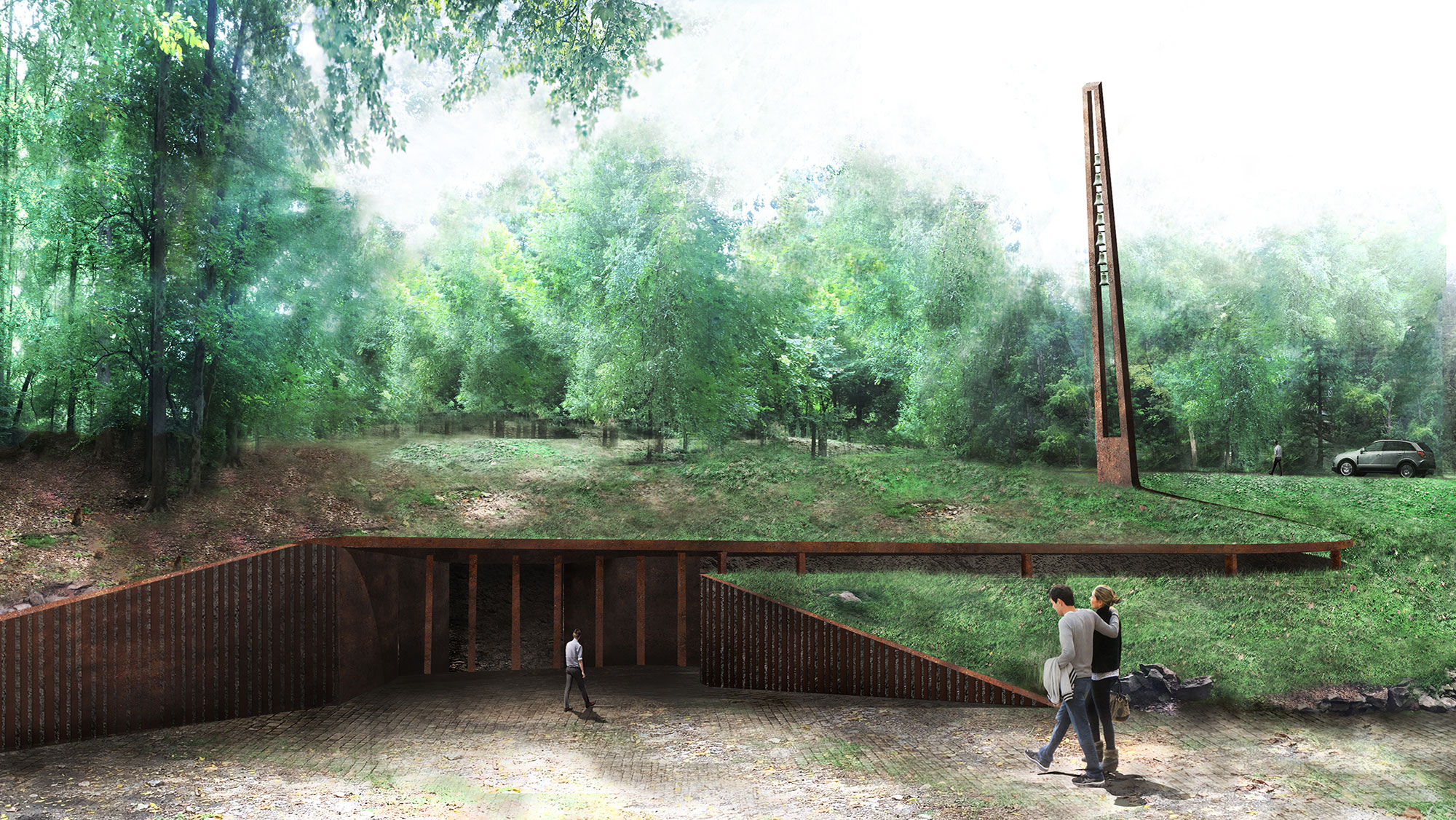

Ebenezer Chapel by Vilalta Studio, Raleigh, North Carolina

Ebenezer Chapel by Vilalta Studio, Raleigh, North Carolina

House in Chihuahua by Productora, Chihuahua, Mexico

House in Chihuahua by Productora, Chihuahua, Mexico

Åre Solbringen by Waldemarson Berglund, Åre, Sweden

Åre Solbringen by Waldemarson Berglund, Åre, Sweden

The core of a kitchen setup is always the counter or island. Today’s homeowners are looking for surfaces that are utilitarian without compromising the overall aesthetic. Plain surfaces with flushed drawers, concealed joints and even hidden electric stoves or sinks are making rounds on social media and in homes.

The core of a kitchen setup is always the counter or island. Today’s homeowners are looking for surfaces that are utilitarian without compromising the overall aesthetic. Plain surfaces with flushed drawers, concealed joints and even hidden electric stoves or sinks are making rounds on social media and in homes. No perfect counter is complete without the right stove. A recessed stovetop not only makes the kitchen seem more spacious but also makes movement and cleaning easier. Traditional burners can come with the headache of cleaning out grime and spillovers and using burner covers can mar the clean look of a kitchen.

No perfect counter is complete without the right stove. A recessed stovetop not only makes the kitchen seem more spacious but also makes movement and cleaning easier. Traditional burners can come with the headache of cleaning out grime and spillovers and using burner covers can mar the clean look of a kitchen. The next step in assembling a minimal kitchen is finding the perfect sink — one that stands out but also blends in. Fewer seams and streamlined fittings can help prevent excess soap and grime buildup and also create the appearance of more room. In line with these needs, designers are now moving away from traditional metal sinks and opting for stone or ceramic options that are more geometric and modern.

The next step in assembling a minimal kitchen is finding the perfect sink — one that stands out but also blends in. Fewer seams and streamlined fittings can help prevent excess soap and grime buildup and also create the appearance of more room. In line with these needs, designers are now moving away from traditional metal sinks and opting for stone or ceramic options that are more geometric and modern. In addition to pots, pans and utensils, displayware is also becoming increasingly popular in kitchen décor. From ornate flower vases to decorative signs and stands, there are options for every kitchen aesthetic. Forust recently developed a 3D printing system that uses wood waste to craft home goods. The sustainable Vine range, designed by fuseproject, includes a vessel, bowl, basket and tray — all of which can be used for a variety of schemes ranging from whimsical cottagecore to minimal monochrome. These pieces are made up of 3D-printed rods that twist and come together to create curved forms without any adhesives. Their simple and versatile design language makes them an easy option to add some warmth to simple spaces.

In addition to pots, pans and utensils, displayware is also becoming increasingly popular in kitchen décor. From ornate flower vases to decorative signs and stands, there are options for every kitchen aesthetic. Forust recently developed a 3D printing system that uses wood waste to craft home goods. The sustainable Vine range, designed by fuseproject, includes a vessel, bowl, basket and tray — all of which can be used for a variety of schemes ranging from whimsical cottagecore to minimal monochrome. These pieces are made up of 3D-printed rods that twist and come together to create curved forms without any adhesives. Their simple and versatile design language makes them an easy option to add some warmth to simple spaces.