Send us a photo. Tell us a story. Win $2,500! Architizer’s 3rd Annual One Photo Challenge is underway with an Early Entry Deadline on May 27, 2022! Start your entry for architecture’s biggest photography competition here.

Not everyone is happy with Day’s End, David Hammons’s massive but easy-to-miss sculpture on New York’s West Side waterfront, which stands squarely across the street from the Whitney Museum of American Art. In a diplomatic yet skeptical piece in ArtReview, critic Evan Moffitt writes that the sculpture raises “uncomfortable questions” about the legacy of New York’s piers, which were once a clandestine meeting point for the city’s queer community, and are now home to jogging paths and wine bars for the one percent.

The implication is that this sculpture, an 18 million dollar Whitney commission, is just the latest example of “gentrifier art.” This fact is particularly irksome to Moffitt because Day’s End is being sold as a memorial to an earlier, grittier incarnation of the city. The Whitney’s official press materials prominently mention the LGBTQ history of the long-since demolished Pier 52, which Hammons’s sculpture resurrects in ghostly outline. For Moffitt, there is a stark contradiction between the marginalized social history that the Whitney is claiming to venerate, and the role the museum has played in transforming the Meatpacking District into a gilded playground.

The sculpture at sunset. Photo by Elvert Barnes.

“The new Day’s End… is a product of immense physical and bureaucratic resources, a framework that is perfect and unchanging,” Moffitt writes, referring to the tremendous amount of legwork that went into ensuring that the sculpture’s slender beams could withstand the changing tides of the mighty Hudson. “This is less reflective of a flaw in Hammons’s design than of how impossible it is to incise a landscape so thoroughly policed and privatized.”

This line of argument is taken further by Kathleen Langjhar in The Architect’s Newspaper, who writes that Hammons’s work “selectively engages” with history, and that much of the praise that greeted the sculpture’s 2021 opening, including from The New York Times, is rooted in “a general attitude that sees culture as an unmitigated good, a solvent for cleansing the wrongs of the past.” On this reading, Day’s End is not just another example of gentrification art, but a cunning attempt to disguise the violent process of displacement that gave rise to the sanitized Meatpacking District we know today.

Like the sculpture itself, these critiques raise more questions than they answer. For one, what is Day’s End actually about? What is it claiming to memorialize, exactly, and on whose behalf? If the Whitney is discussing this work in a self-serving way – and of course they are – does this necessarily define what the work is in itself?

There seems to be more going on here than meets the eye. For one thing, why did Hammons, who has spent almost six decades refusing to cooperate with major art institutions like the Whitney, suddenly make an exception in order to create this work? Given everything we know about Hammons, who has spent his career using the tactics of conceptual art to advocate for the Black community, it seems unlikely that he did it to advance the interests of art museums and property developers. And given the mercurial brilliance of his body of work, it is also hard to see him as a dupe.

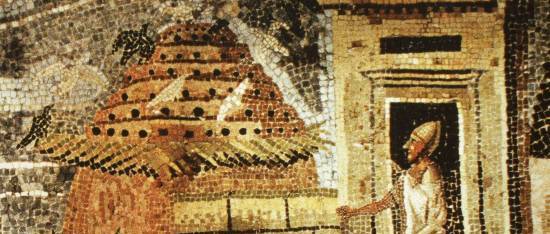

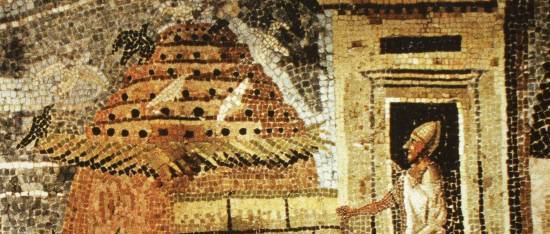

According to David Hammons and Whitney director Adam Weinberg, the initial inspiration for Day’s End was not gentrification, queer history, or any of the other topics that have dominated discussion of the work, but rather the previous artwork that once stood on the site: Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural intervention, which was also titled Day’s End. In 1975, the self-described “anarchitect” cut a large opening on the river-facing facade of the Pier 52 shed, transforming the abandoned pier into a kind of observatory or makeshift cathedral. (Matta-Clark was reportedly inspired by the shed’s resemblance to early Christian basilicas). At “day’s end,” golden light would pour into the gritty space, a glimpse of heaven in the midst of a postindustrial hell. It stood for just three years before the shed was demolished in 1978, the same year that Matta-Clark passed away from pancreatic cancer at age 35.

The fact that Hammons had Matta-Clark in mind when he conceived the piece, and not the pier’s history as a nexus of queer culture, has troubled a number of commentators. It turns out that Matta-Clark resented the presence of the LGBTQ community on Pier 52. Although Matta-Clark had no more right to the space than they did – his installation was created without permits, under cover of night – he padlocked the entrances to the shed while he was working on his piece. He described the frequent visitors to the space as “menacing characters,” part of a “sadomasochistic fringe,” and complained that their presence detracted from the power of his work. While Matta-Clark was interested in reclaiming the dark, abandoned corners of New York for art, he had little time for the people who had already found a use for these spaces. Moffitt complains that Hammons’s piece, by memorializing Matta-Clark, “contributes to the hagiography of a homophobe.”

Ironically, while Matta-Clark may not have liked the LGBTQ subculture that thrived alongside the original Day’s End, his work lives on in public memory in large part due to the work of photographer Alvin Baltrop, a gay, African-American artist who lovingly documented sunbathers on the piers in the 70s. The very community Matta-Clark resented is, it seems, responsible for the long afterlife his installation has enjoyed.

This is the kind of irony that Hammons appreciates more than his critics do. Moffitt bristles at the fact that the plaque adjoining Day’s End mentions Matta-Clark and not Baltrop or the history of cruising at the piers, claiming that these omissions amounts to violent erasure. But as Jacques Derrida would note, every attempt to commemorate or conserve is simultaneously an act of erasure. If this is violence, it is a kind of violence that is inscribed in the essence of signification itself. It would be impossible to encompass the entire history of the piers in the space of a plaque.

Of the work, Hammons has said “a great tailor makes the fewest cuts.” Photo by Elvert Barnes

By leaving the form of the sculpture radically open, Hammons’s work speaks to the impossibility of his critics’ demand – that is, the impossibility of an objective monument. Every monument is a “cut” in the historical record, privileging some elements over others. The best one can do is create a space for discussion. And Hammons’s Day’s End, in echoing the architectural form of Pier 52, literally does this – that is, it creates space. That is all it does, really. Its form is an outline. As Hammons noted when discussing the piece, “a great tailor makes the fewest cuts.” Without speaking to it directly, Hammons’s Day’s End provoked a discussion about the queer history of the piers. That history – and other histories, yet unmentioned – is simply part of the work, regardless of the intentions of its patrons and creators. The work exceeds the Whitney, and exceeds Hammons.

Throughout his career, David Hammons has explored the mystic power of objects and materials. He once said that he spends “85 percent” of his time on the streets, observing his environment and gathering inspiration. His most enduring works are made from discarded materials, from garbage. He has created art from liquor bottles, hair, felled telephone poles, garbage bags, and even snow.

While Hammons’s work is deeply political, it is never didactic. Take his famous 1986 installation, Higher Goals. Working out in the open, on the streets of Brooklyn, Hammons decorated felled telephone poles with bottle caps. He then fixed basketball hoops to the top of the poles and placed them upright again. The hoops stood 20 to 30 feet in the air, far higher than any player could comfortably reach. “It takes five to play on a team, but there are thousands who want to play,” Hammons explained “Not everyone will make it, but even if they don’t, at least they tried.”

With brutal clarity, this piece illustrated the way fame is dangled in front of Black youth, a means of keeping marginalized communities complacent with false hope. And yet, there was more to it than that. The intricately decorated hoops also spoke to the resilience of the Black community, how the youth still dare to dream even in desperate circumstances. Looking up at the sculptures, one wonders what could happen if that energy could be channeled somewhere else.

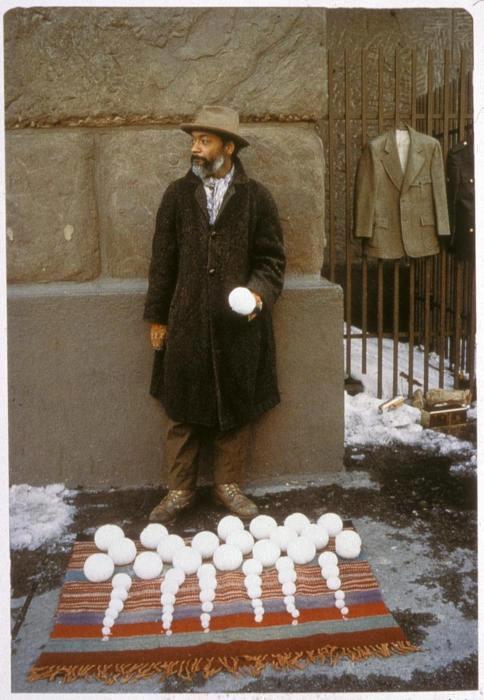

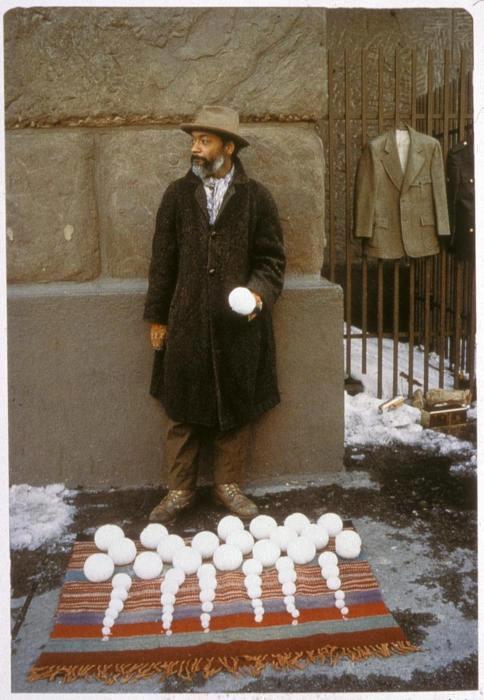

Another example of a work by Hammons that defies easy interpretation is his Bliz-aard Ball Sale in 1983. This performance piece was deceptively simple. Hammons literally sold snowballs on the side of the road. Perfect snowballs, made with expert care and available in different sizes. At one level, this whimsical performance was a commentary on capitalism’s ability to turn anything into a commodity. It was a joke. But in another sense, there was something beautiful about the snowballs, their delicacy and ephemerality. By selling them, he was offering customers a taste of their childhood, a tactic not unknown to marketers. There is an art in marketing, the work suggests. Perhaps it is a dark art, but it is an art all the same.

“[ H ] David Hammons – Blizaard Ball Sale (1983)” by Cea. is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Day’s End is another Hammons work that is mischievous in its undecidability. It certainly is an homage to Gordon Matta-Clark, an artist who Hammons never crossed paths with, but who shared Hammons’s interest in art’s power to transform forgotten spaces and materials. But it pointedly does not resemble Matta-Clark’s installation. There is no half-moon in the new Day’s End, no play of light and shadow. The sculpture simply points to its original context, and in doing so has provoked a lively debate over the legacy of a small part of the waterfront that, previously, no one thought about very much.

If Hammons’s Day’s End is a monument at all, it is a very non-traditional one. In bolder moments, one could even call it an “anti-monument.” The work advances no specific narrative, presenting only a frame for contested histories.

Cover photo by Elvert Barnes

Send us a photo. Tell us a story. Win $2,500! Architizer’s 3rd Annual One Photo Challenge is underway with an Early Entry Deadline on May 27, 2022! Start your entry for architecture’s biggest photography competition here.

Microlibrary Warak Kayu by SHAU, Semarang, Indonesia

Microlibrary Warak Kayu by SHAU, Semarang, Indonesia

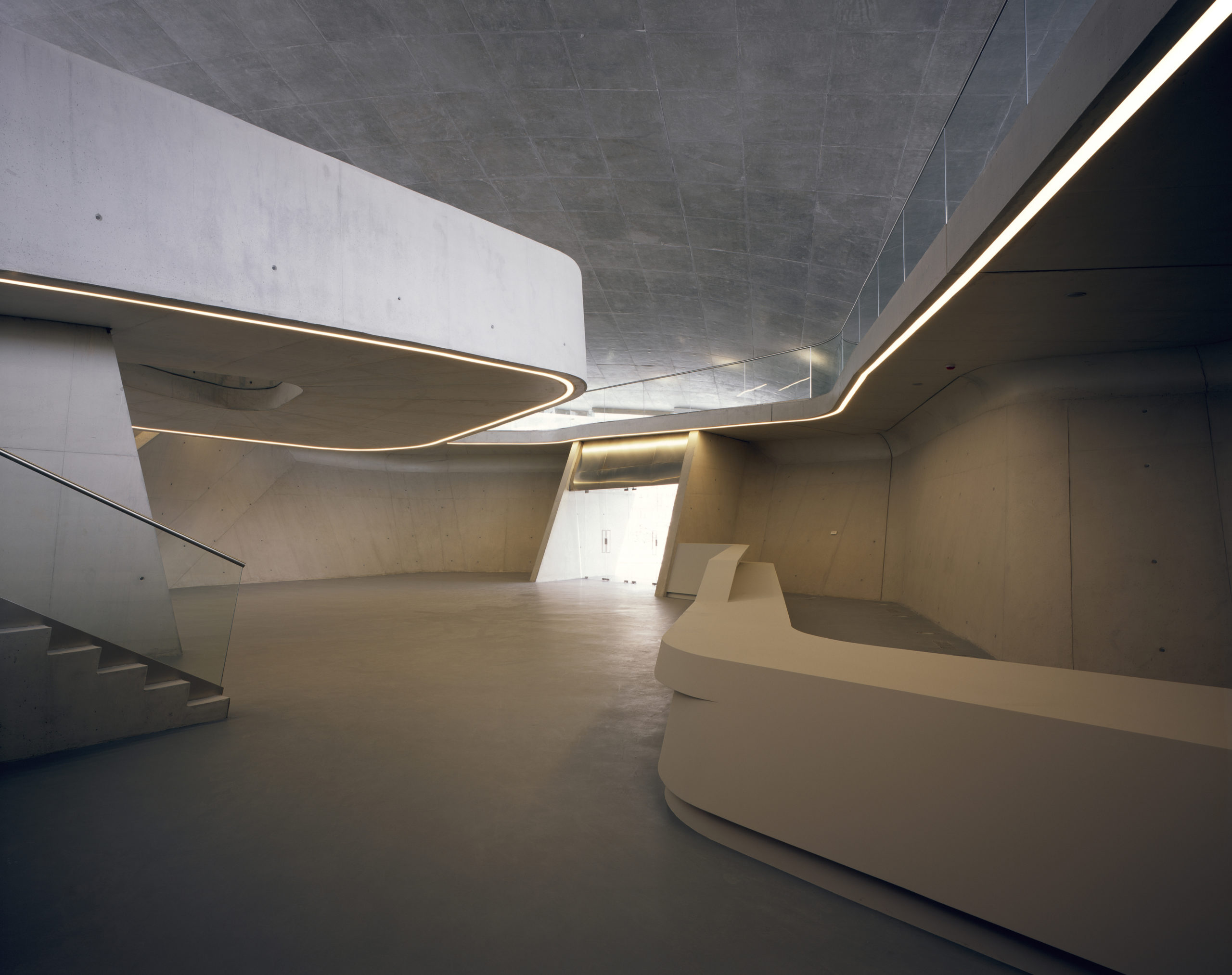

City Lounge of Zhongshan Road by The Design Institute Of Landscape & Architecture China Academy Of Art CO.,LTD, Jiaxing, China

City Lounge of Zhongshan Road by The Design Institute Of Landscape & Architecture China Academy Of Art CO.,LTD, Jiaxing, China

Microlibrary Bima by SHAU, Bandung, Indonesia

Microlibrary Bima by SHAU, Bandung, Indonesia

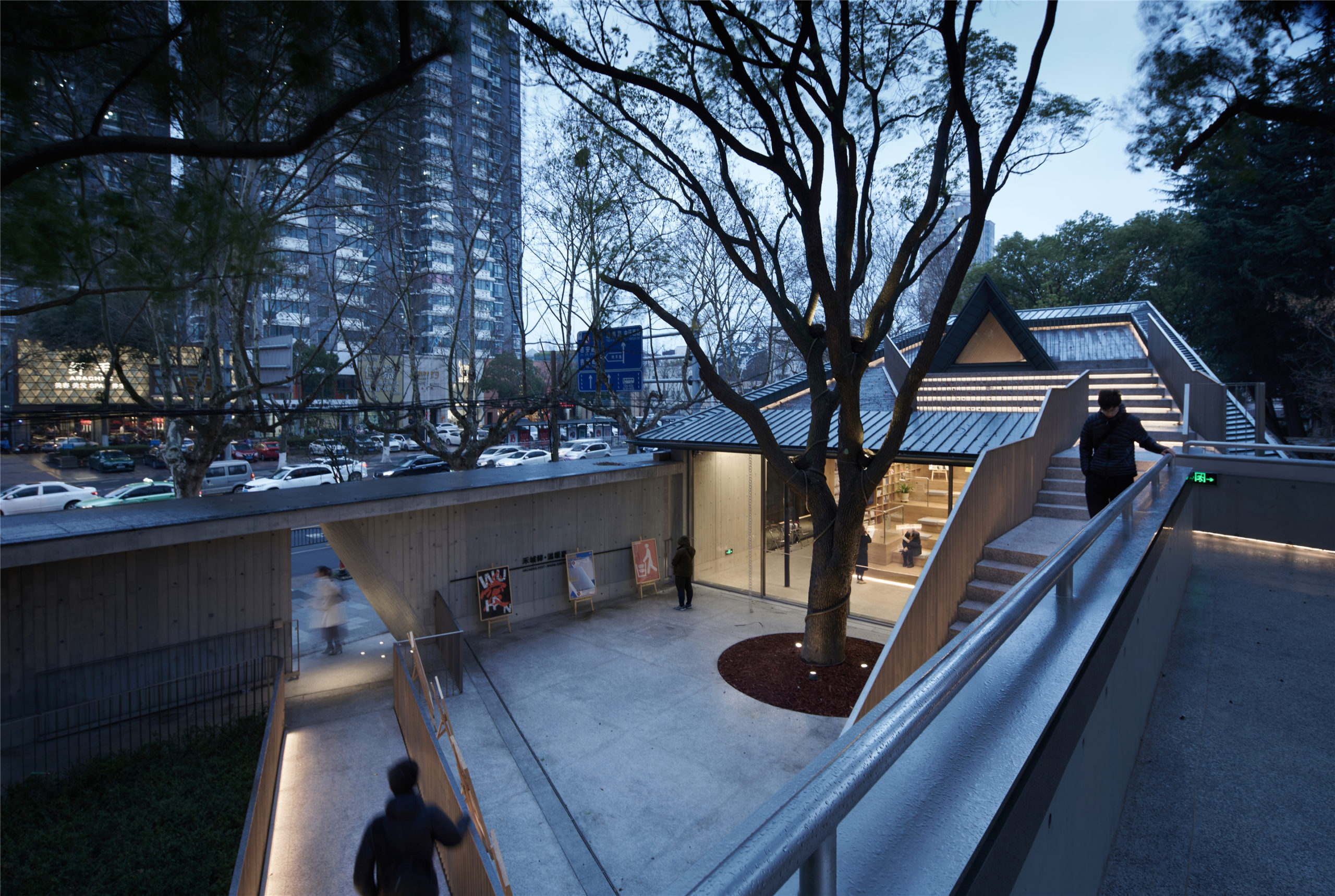

Readers’ House by Atelier Diameter, Beijing, China

Readers’ House by Atelier Diameter, Beijing, China

The Quarter for Jewish Culture Festival by BudCud, Kraków, Poland

The Quarter for Jewish Culture Festival by BudCud, Kraków, Poland

Mobile Library by ArchiWorkshop, Seoul, South Korea

Mobile Library by ArchiWorkshop, Seoul, South Korea

VAC-LIBRARY by Farming Architects, Hanoi, Vietnam

VAC-LIBRARY by Farming Architects, Hanoi, Vietnam

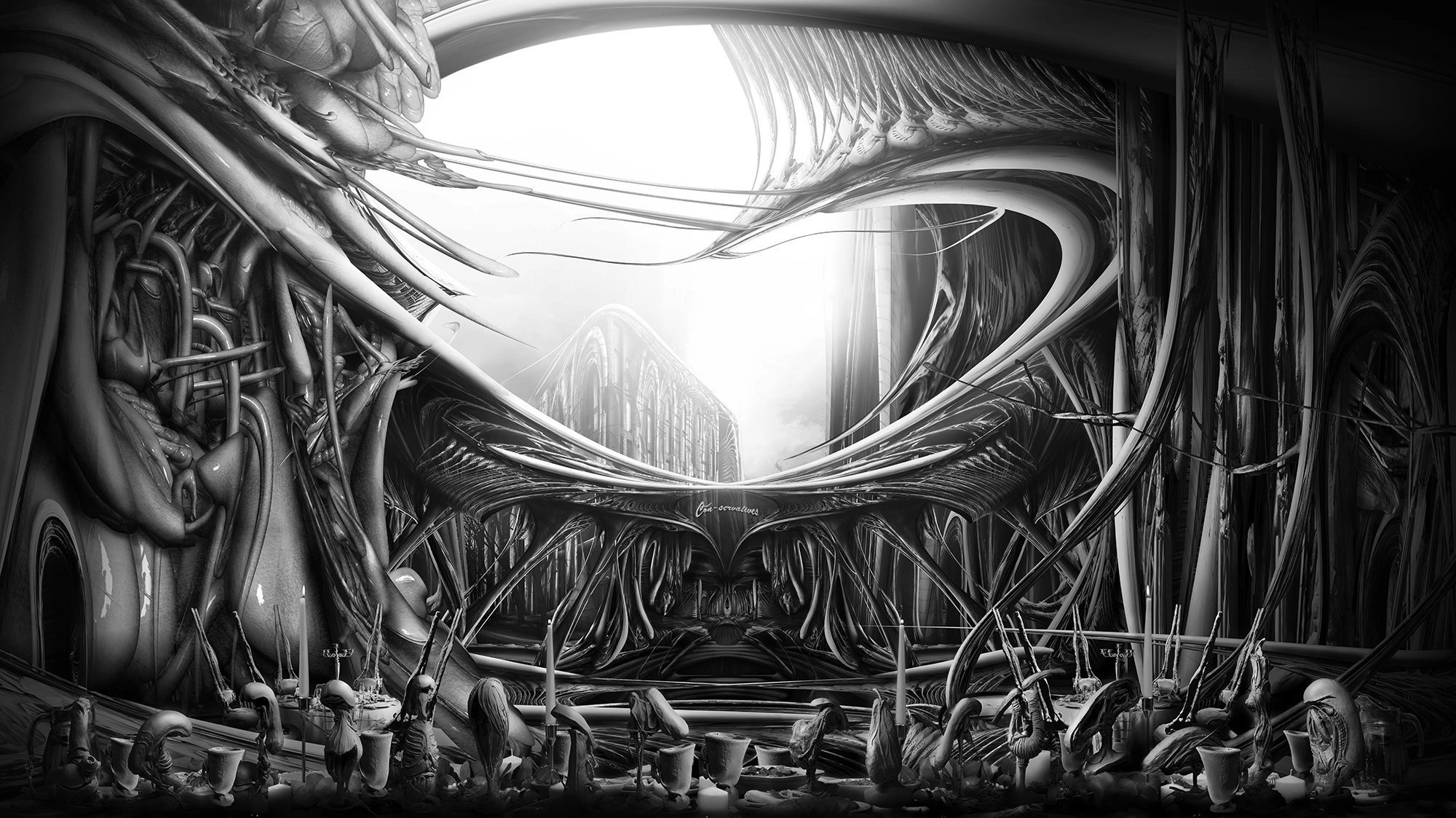

Paul Keskeys: Congratulations on your success! What does winning the 2022 One Rendering Challenge mean to you?

Paul Keskeys: Congratulations on your success! What does winning the 2022 One Rendering Challenge mean to you? What were the primary challenges of conceiving your work, from forming the idea to the actual physical process of rendering?

What were the primary challenges of conceiving your work, from forming the idea to the actual physical process of rendering? Did you use your usual techniques and software for creating this rendering? If you tried something different, how did that go?

Did you use your usual techniques and software for creating this rendering? If you tried something different, how did that go?

What one tip would you give students and architects looking to win next year’s One Rendering Challenge?

What one tip would you give students and architects looking to win next year’s One Rendering Challenge?

In her preface, Kloter highlights a key disparity in numbers: “In its 2020 annual report, the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) revealed that 50% of the 26,977 students enrolled in NAAB-accredited architecture programs – B. Arch, M. Arch, and D. Arch– were female. This is a number that has been improving since the 1970s, yet the percentage of women who obtained their architect license, achieve upper management positions, become partners and own architectural firms have not increased at the same rate as men have. To date, data from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) 2021 NCARB by the Numbers report shows that only 24% of the 121,997 registered architects in the United States are female.”

In her preface, Kloter highlights a key disparity in numbers: “In its 2020 annual report, the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) revealed that 50% of the 26,977 students enrolled in NAAB-accredited architecture programs – B. Arch, M. Arch, and D. Arch– were female. This is a number that has been improving since the 1970s, yet the percentage of women who obtained their architect license, achieve upper management positions, become partners and own architectural firms have not increased at the same rate as men have. To date, data from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) 2021 NCARB by the Numbers report shows that only 24% of the 121,997 registered architects in the United States are female.” Kloter’s book contains a wealth of practical advice to balance home and work life, as well as powerful motivational tools to instill belief in women, encouraging them to embrace their capabilities to be renowned architects and incredible mothers. The following quotes provide a teaser for the words of wisdom that you can find throughout the book:

Kloter’s book contains a wealth of practical advice to balance home and work life, as well as powerful motivational tools to instill belief in women, encouraging them to embrace their capabilities to be renowned architects and incredible mothers. The following quotes provide a teaser for the words of wisdom that you can find throughout the book: