Judging is now underway for the 10th Annual A+Awards Program! Want to earn global recognition for your projects? Sign up to be notified when the 11th Annual A+Awards program launches.

The word “modernity” was coined by the French poet Charles Baudelaire, who used it to describe the “fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis.” In his 1867 essay “The Painter of Modernity,” Baudelaire exhorts artists to reject classicism and embrace the flickering, tragicomic life of the streets. He argues that the modern artist must become a flaneur, or connoisseur of urban life, if they hope to produce work that is vital and alive.

Watercolor and ink sketch by Constantin Guys (1802 – 1892). Baudelaire named Guys the ultimate “painter of modernity” due to the interest he took in city crowds.

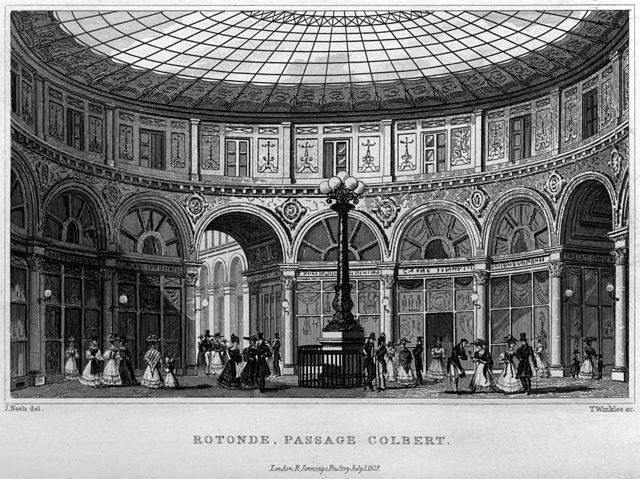

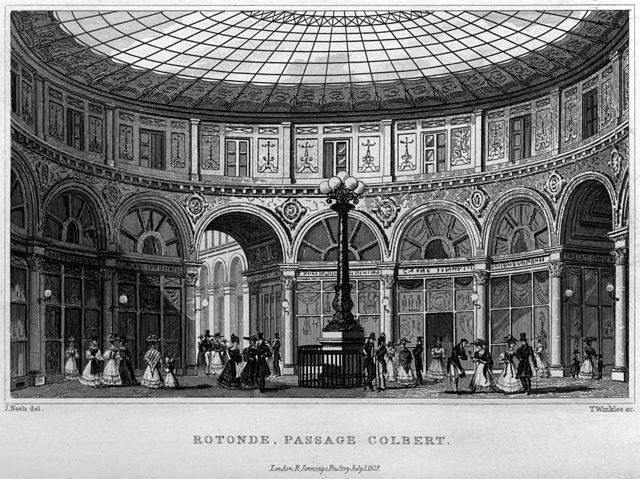

For Baudelaire, the quicksilver newness of modernity was made possible by architecture, by the way his fellow Parisians moved through built spaces. And the most interesting built spaces in Baudelaire’s Paris were the arcades. Constructed in the first half of the 19th century, the Paris arcades were covered walkways that housed various shops, newsstands and cafes. With vaulted ceilings made from glass and iron, the arcades offered an elegant respite from the grime and noise of the city street. In guidebooks to Paris from the time period, the arcades were always listed as a major attraction.

The philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin believed the arcades were the most important architectural form of the century. In his unfinished masterpiece, The Arcades Project, written between 1927 and 1940, Benjamin attempts to reconstruct Baudelaire’s Paris using an experimental method, assembling thousands of textual fragments into a kind of collage. His goal was not simply to write a historical narrative, but to bear witness to the birth of modernity. The result is a fascinating meditation on the dialectical relationship between architecture and history — a subject that is just as relevant today as it was in Benjamin’s time.

1831 engraving of the rotunda at Galerie Colbert. Along with the nearby Galerie Vivienne, Galerie Colbert was one of Paris’s largest and most famous arcades.

The most unique aspect of The Arcades Project is its structure. The book opens with a series of impressionistic but otherwise conventional essays, establishing the historical period with overviews of subjects such as the origin of the arcades, the history of the Paris Commune, and Baron Haussmann’s dramatic redesign of Paris between 1850 and 1870, in which many of the arcades were destroyed to make way for the wide boulevards and uniform city blocks that define the city as we know it today. After these sections, however, things take a more radical turn.

The majority of the text is comprised of pieces that Benjamin calls “convolutes,” which are textual fragments that he collected through his vast reading on the period. Quotations from newspapers, letters and academic texts are placed alongside the author’s own reflections. The fragments are ordered by an alphabetical system, with the letters corresponding to different topics. For example, section A concerns the arcades; B is about fashion; and C, Ancient Paris and the Catacombs. Some of the sections combine topics in an idiosyncratic way, such as D, which covers both boredom and Nietzsche’s concept of “Eternal Return.” A number of fragments are cross-referenced, corresponding to more than one letter, which allows readers to see how these different ideas relate to each other, like points in a web or constellation.

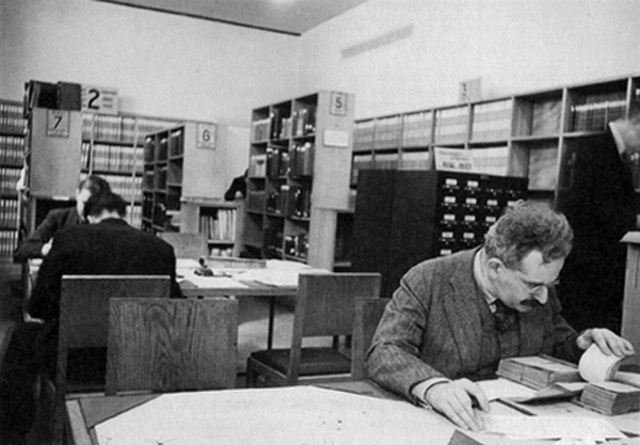

When Walter Benjamin wasn’t strolling through the arcades, he spent most of the 1930s in Paris’s public libraries and archives.

All told, The Arcades Project isn’t written so much as constructed, like a building. The ordering system of the convolutes resembles the directory of a massive shopping mall. Readers of this book do not follow a narrative or argument, but move through a kind of endless exhibition. They enter into the period, discovering it for themselves.

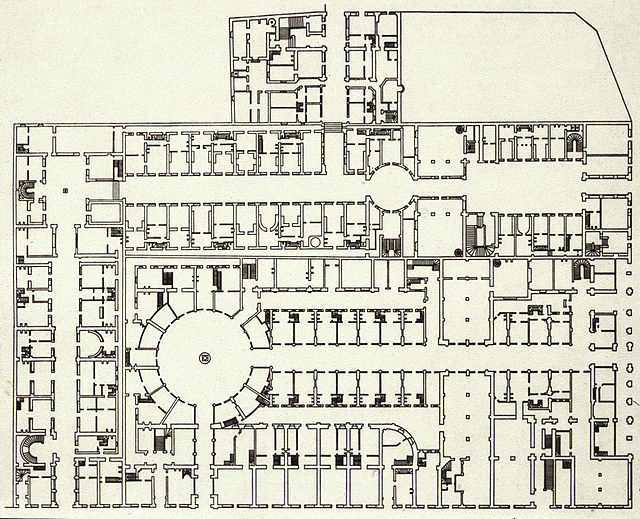

The book begins with a note that the majority of the Paris arcades were built in the “decade and a half after 1822.” Readers learn that the arcades were made possible by the “boom in the textile trade” and “the advent of building in iron.” This was long before Baron Haussmann’s transformation of Paris. The arcades really belong to an earlier era, before the Second Empire, before even Baudelaire.

As Benjamin explains, Paris in the 1820s was a filthy, crowded, “subterranean” city, prone to outbreaks of cholera and revolution. And yet the arcades, which were open to the public, were glittering modern spaces, temples of the new religion of consumerism. At their entrance were boot scrapers, simple iron tools built into crevices in the wall that visitors would use to scrape the city muck off the soles of their shoes, a type of ritual cleansing.

Galerie Colbert in 1900

It was in the arcades that the flaneur, Baudelaire’s archetypal city wanderer, could contemplate the crowd as an aesthetic spectacle. Urban life, in its messiness and variety, now had an elegant stage on which it could be observed.

The iron and glass ceilings of the arcades suggested that these spaces were harbingers of a utopian future. As Benjamin points out, the only other place city dwellers were likely to encounter this type of construction was in exhibition halls such as the Crystal Palace, in which new technologies were often debuted. New technologies were introduced in the arcades as well. Benjamin notes that “they are the scene of the first gas lighting.”

Passage Verdeau today. This was one of Benjamin’s favorite arcades to visit as it was home to dozens of bookstores and antique shops. Built in 1847, it was one of the last arcades to be constructed.

In a fascinating paragraph, Benjamin argues that the appearance of “the new” always draws the imagination back to “elements of prehistory, that is of a classless society.” A dream about the future is always also a wish to recover what one has lost. Benjamin believes it is no coincidence that socialist thinking — especially of the utopian variety — exploded in France at the same time that the arcades appeared. Charles Fourier’s famous phalanstery, his scheme for a self-contained, egalitarian living and working community, was essentially “a city of arcades,” Benjamin argues. It was the arcades that showed Fourier that variegated human activities could be organized under a single roof.

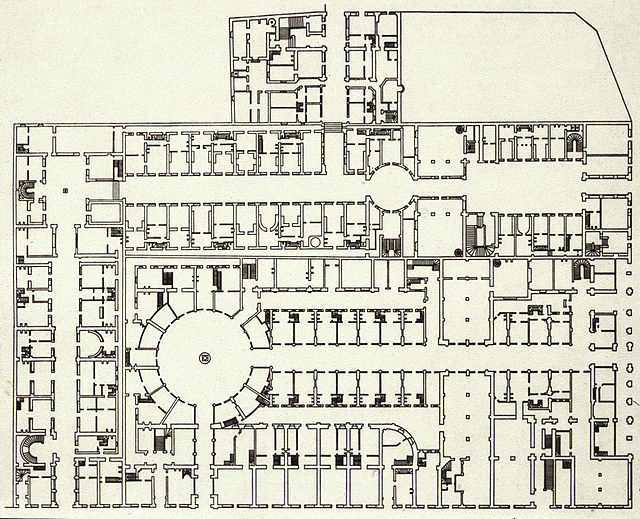

1826 floor plan of Galeries Colbert and Vivienne

When Benjamin mailed his early drafts of The Arcades Project to colleagues, many found it baffling. Why give all this attention to 19th century shopping malls? How was this relevant at a time when fascism was on the move all across Europe? Walter Benjamin was a German Jew and a committed Marxist. When he wrote The Arcades Project, he was living in France as a political exile. And yet, he believed that the best use of his time and talent was to investigate the conditions that gave rise to modernity, especially the emergence of the commodity form. Here, he felt, he would uncover the deep roots of fascism, and perhaps better understand how it could be resisted.

Writing under the shadow of Nazism, Benjamin understood modernity differently than Baudelaire had. He had mixed feelings about it, or to use his terminology, he approached it “dialectically.” While modernity offered new possibilities for freedom, in the end it had created the conditions for fascism. Without modern technology, the Nazi regime would never have been able to exercise the level of destructive control that they did. Even the spectacle of the crowd, which Baudelaire had celebrated as a symbol of diversity, was menacingly transfigured into an image of uniform state power in the Nazi propaganda films of Leni Riefenstahl. The crowd, like so much else, had been engineered for totalitarian ends.

When Walter Benjamin sat down to write his book, the spectacle of the urban crowd had been transformed into something menacing and authoritarian.

Something had obviously gone very wrong with modernity. What was it? This is the question Benjamin asks in The Arcades Project. Importantly, he doesn’t seek to answer it, at least not in any direct way. What he does instead is try to bring Baudelaire’s Paris to life with his collage method. His hope is that these juxtapositions of facts, quotations, and speculative commentaries will cause a “dialectical image” of the period to “flash up” in the reader’s mind, allowing them to see things that cannot be described in a straightforward way: the diverted hopes and buried possibilities of the period.

The Arcades, as a site of commerce, played an important role in the history of the commodity form. This uncanny photo of a Parisian storefront was taken by the street photographer Eugene Atget in the early 20th century.

Benjamin saw the modern world as a kind of dream, or “phantasmagoria,” in which the true relations between people are obscured by capitalist ideology and commodity fetishism. The arcades, then, were the earliest dream factories, a spectacle of consumption in which the actual history of the objects on display, and the labor that went into producing them, was deliberately concealed.

Visitors to the arcades were encouraged to think of themselves as consumers, maybe even flaneurs, but never as exploited workers. While the form of life Baudelaire celebrated produced flashes of revolutionary possibility, in the end it had lulled the masses into a false consciousness, preventing them from taking hold of their own destiny.

The goal of The Arcades Project was to snap readers out of the capitalist dream so they could resist the fascist nightmare. Like Freud, Benjamin believed that one needed to descend into the murky depths of the past in order to recover the insights they needed to move forward. If there is one sentiment that runs through the project, it is hope — hope of a desperate sort.

Galerie Vivienne in 1905

In 1940, Walter Benjamin died at the age of 48 in Portbou, Spain while in police custody. He was fleeing Nazi-occupied France when he and his companions were arrested by Spanish authorities, who told them that they would be deported back to France the following day. Believing he would be sent to a concentration camp, Benjamin took a deliberate overdose of morphine in his prison cell. However, the next day his companions were all released and allowed to continue on their journey to America. If Benjamin had held on just one more day, he could have traveled with them.

The tragic story of Benjamin’s death is often told with the suggestion that it carries a poignant lesson. However, I never understood what that lesson was supposed to be. So in lieu of commentary, I am simply going to leave it here, as Benjamin would have, as a stray piece of the historical puzzle.

Walter Benjamin’s work remains an important resource, not only for philosophers and cultural critics, but for architects. Architects today would do well to think about cities the way Benjamin did, as living collages that place the present in conversation with the past. If architects studied Benjamin, they would learn to see their projects not as stand alone entities, but as points of light within a vast, ever-shifting constellation.

Judging is now underway for the 10th Annual A+Awards Program! Want to earn global recognition for your projects? Sign up to be notified when the 11th Annual A+Awards program launches.

In her preface, Kloter highlights a key disparity in numbers: “In its 2020 annual report, the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) revealed that 50% of the 26,977 students enrolled in NAAB-accredited architecture programs – B. Arch, M. Arch, and D. Arch– were female. This is a number that has been improving since the 1970s, yet the percentage of women who obtained their architect license, achieve upper management positions, become partners and own architectural firms have not increased at the same rate as men have. To date, data from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) 2021 NCARB by the Numbers report shows that only 24% of the 121,997 registered architects in the United States are female.”

In her preface, Kloter highlights a key disparity in numbers: “In its 2020 annual report, the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) revealed that 50% of the 26,977 students enrolled in NAAB-accredited architecture programs – B. Arch, M. Arch, and D. Arch– were female. This is a number that has been improving since the 1970s, yet the percentage of women who obtained their architect license, achieve upper management positions, become partners and own architectural firms have not increased at the same rate as men have. To date, data from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) 2021 NCARB by the Numbers report shows that only 24% of the 121,997 registered architects in the United States are female.” Kloter’s book contains a wealth of practical advice to balance home and work life, as well as powerful motivational tools to instill belief in women, encouraging them to embrace their capabilities to be renowned architects and incredible mothers. The following quotes provide a teaser for the words of wisdom that you can find throughout the book:

Kloter’s book contains a wealth of practical advice to balance home and work life, as well as powerful motivational tools to instill belief in women, encouraging them to embrace their capabilities to be renowned architects and incredible mothers. The following quotes provide a teaser for the words of wisdom that you can find throughout the book: