Jet Geaghan is an Architect based in Woods Bagot’s Sydney studio. For Jet, every building should be conceived with purpose, expertise and wit. Clarity of communication is fundamental to his work, whether it be in a design gesture, construction detail, or cultural testimony.

Artificial Intelligence is the Frankenstein’s creature of the digital era. The possibility of the invention surpassing the inventor beguiles our collective imagination – conjuring emotions as far-ranging as hope, trepidation and even fear. Unnerving reports of a Google chatbot displaying sentience in June plays on our conscious, forcing us to consider the ramifications of an AI that fears us as much as we fear it.

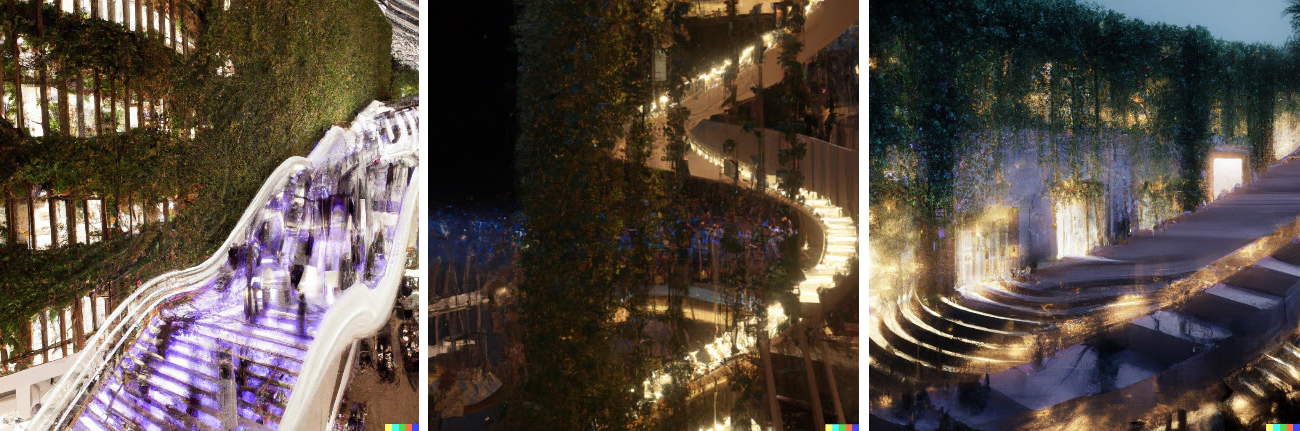

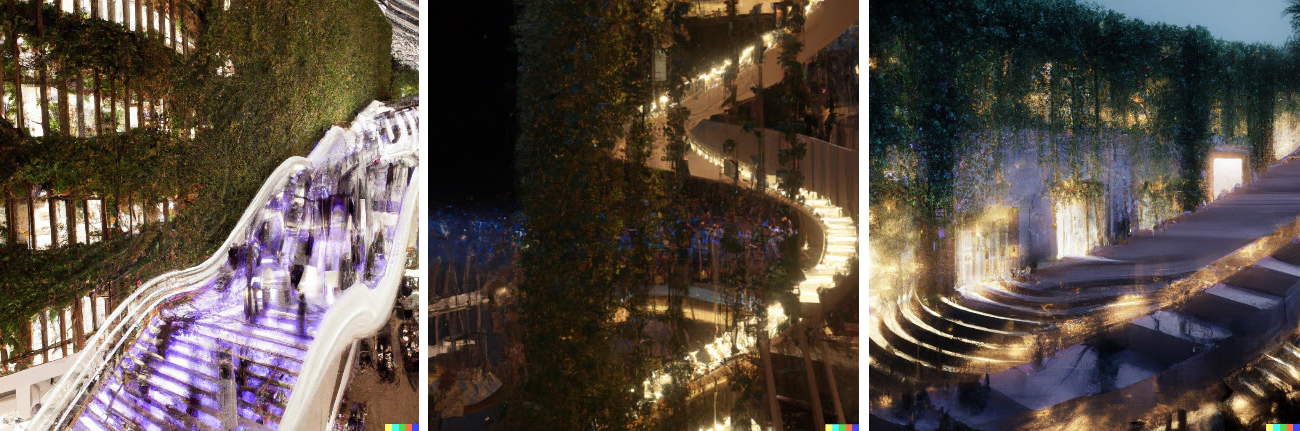

The quickening pace of AI’s development is both alarming and exciting, fuelling speculation about our own obsolescence. It once seemed irrefutable – even amongst the pioneers of machine intelligence – that only humans could create art. Now, image generation AI like DALL E-2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion use machine learning neural networks to create original, breathtakingly realistic images from a text description that would look as at home on a gallery wall as they would as concept images in an architectural bid (see fig.1).

These algorithms challenge humanity’s ownership of creativity as we know it, but they do not herald the designer’s last days. Instead, AI will be harnessed as a powerful tool that (1) allows for time better spent and (2) unlocks new dimensions of creative ideation. Both functions will synthesize the role of the designer towards a more productive, augmented future.

Time Better Spent

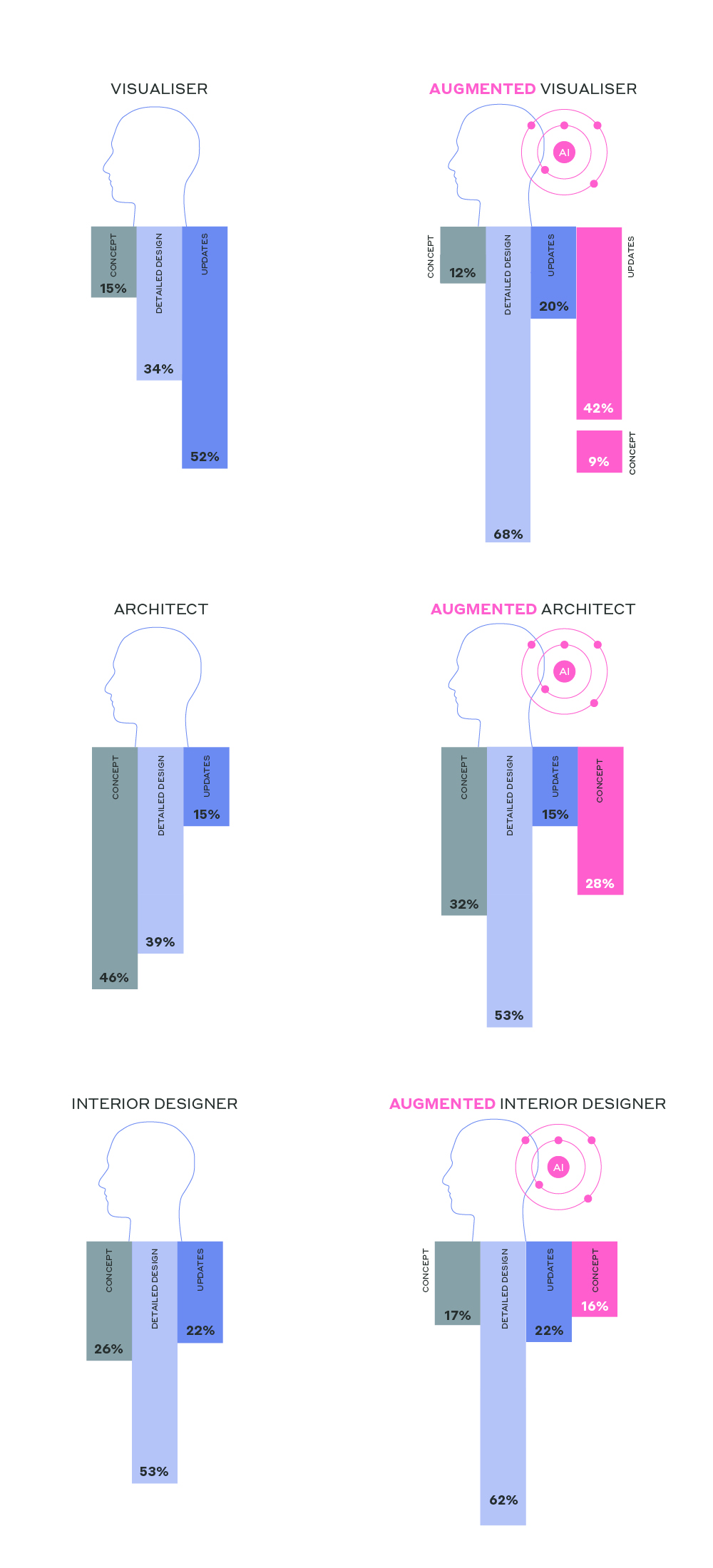

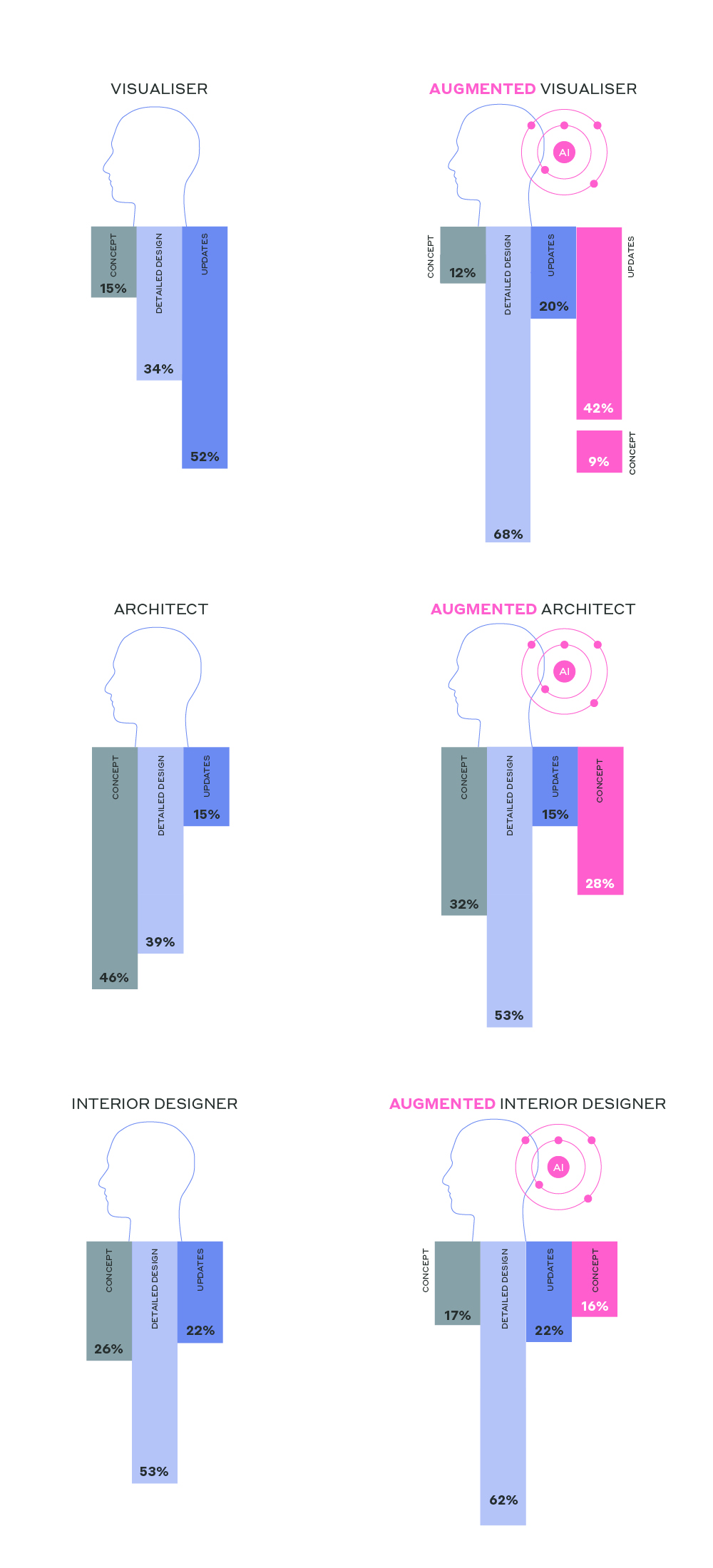

Using real data from Woods Bagot timesheets over the period of one year, this diagram postulates the gains in productivity that AI could provide by automating repetitious tasks across different project phases. The time freed up could be funneled back into meaningful design tasks – resulting in better use of resources and better outcomes for clients and end users.

The history of technological advancement is defined by massive leaps forward that have seen time-consuming, repetitive processes automated, fundamentally changing what humans can produce. AI continues this tradition by rapidly becoming more affordable and higher performing. Stanford University’s 2022 AI Index Report shows that the cost to train an image classification system has decreased by 63.6%, while training times have improved by 94.4% since 2018. The result of the swift development of AI is that designers – hired for their creative reasoning and expertise – could be freed from the bonds of mundane tasks.

These were developed with DALL-E 2 in a 20-minute timeframe, using variations around the prompt ‘feature lobby staircase with soft background lighting at night.’ Rather than generating a design, AI generated images help to quickly explore mood, materiality and character for early concepts.

In our inexorably visual world, AI like DALL E-2, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney streamline the image-making process. Today’s design concepts are expected to be communicated with photorealism and multi-dimensional dynamism for clients or buyers to assess. For designers, image production is a painstakingly meticulous and lengthy process, requiring precision and ingenuity in equal parts. Image generating AI, which produces beautiful visuals in minutes, dampens these pressures.

Even the smallest amendment to existing imagery can take many hours in human hands. With careful design supervision, an algorithm can produce sketch-like illustrations of space and mood in minutes. Here is an image of an abandoned power station placed next to an image of that space reimagined with DALL-E 2 as a contemporary hotel reception celebrating its industrial history.

These new tools give designers a speedy visual foundation on which to build an aesthetic, while still allowing them the depth of inquiry and emotional reasoning pivotal to the development of strong design concepts. The process of drawing a design unveils as many problems as it does solutions – image generating AI allows designers to arrive at the problem-solving stage quicker.

Unlocked Creative Ideation

AI presents a radical new method for exploring ideas that are liberated from the distraction and friction of architectural realities. Through these new methods of discovery, we see creativity redefined as something shared with AI.

Visions of New York City in an alternate future, created with DALL-E 2 (left) and Midjourney (right).

Unembarrassed and unencumbered by accepted strictures, image generating AI tests the bounds of convention by producing limitless possibilities. Though more whimsical than workable for now, these fresh visual takes on design briefs see AI push creative ideation – creating room for the unexpected. By providing DALL-E 2 with a number of text prompts we’re able to see a New York City in an alternate future – its iconic brownstone and leafy Central Park reimagined in entirely novel configurations.

This exploration challenges human assumptions of creative authorship, reframing it as something shared with AI. Though the ruling has since been overturned, the Australian Federal court’s 2021 decision to permit AI systems to be named as the inventor on Australian patent applications is a strong indicator of this incoming overhaul of our understanding of creativity.

Designers develop new ways as well as new things. The future will see designers explore the potential of using AI to improve working processes – unburdening their talent for exploration of ideas, testing, decision making and evaluation. Visualisation tools are already used for testing the success of different materials or geometries before committing to their application, or to measure variables like acoustics, daylighting and airflow. As it develops, AI of this ilk can clarify these judgments – making for easier decision making and better built outcomes.

Here is a photograph of the 275 Kent Street redevelopment, Sydney. Below is a DALL-E 2 interpretation of the key parameters of the brief.

What this comparison illustrates is that, while compelling, this tool cannot digest important factors like context, functionality or human experience. AI imagery cannot replace the understanding, inquiry and decisions of a designer.

AI’s capacity for the testing of ideas is demonstrative of how it will revolutionize workflow and electrify the creativity of design practitioners. Yet it is the directing and evaluating of ideas that requires human judgement to drive the preferred outcome. Design is decision-making, and that remains inherently human.

An Augmented Future

The evolution of AI and design move in tandem. Rather than be replaced, the next generation of designers will be collaborators with AI. This necessitates a new skillset: the adaptive reasoning to evaluate and synthesize the work of machines and a fluency in the computational logic that underpins AI creativity. The designers of the future will focus on creative investigations that require appraisal, interpretation, and sophisticated empathy – such as how a building connects with its site, the cultural ramifications of manufacture or construction, the lived experiences of inhabitants, communities and visitors and the ongoing strain on climate, ecologies and finite resources.

The role of designers has always evolved as new instruments have emerged, but the vitalness of a distinctly human judgement to wield these instruments remains the throughline. To deliver empathetic, reasoned designs, AI needs the human-hand. Likewise, for unrestrained ideation and visual streamlining, delegating to AI will become a necessity in the competitive architectural marketplace. This reciprocal relationship that makes AI a tool that will develop alongside its trade, not one that will leave it behind.

How can architecture be a force for good in our ever-changing world? During Future Fest, we’ll pose this question to some of the world’s best architects. Launching in September, our three-week-long virtual event will be 100% free to attend. Register here!