Australian student invents affordable electric car conversion kit

Australian design student Alexander Burton has developed a prototype kit for cheaply converting petrol or diesel cars to hybrid electric, winning the country’s national James Dyson Award in the process.

Titled REVR (Rapid Electric Vehicle Retrofits), the kit is meant to provide a cheaper, easier alternative to current electric car conversion services, which Burton estimates cost AU$50,000 (£26,400) on average and so are often reserved for valuable, classic vehicles.

Usually, the process would involve removing the internal combustion engine and all its associated hardware, like the gearbox and hydraulic brakes, to replace them with batteries and electric motors.

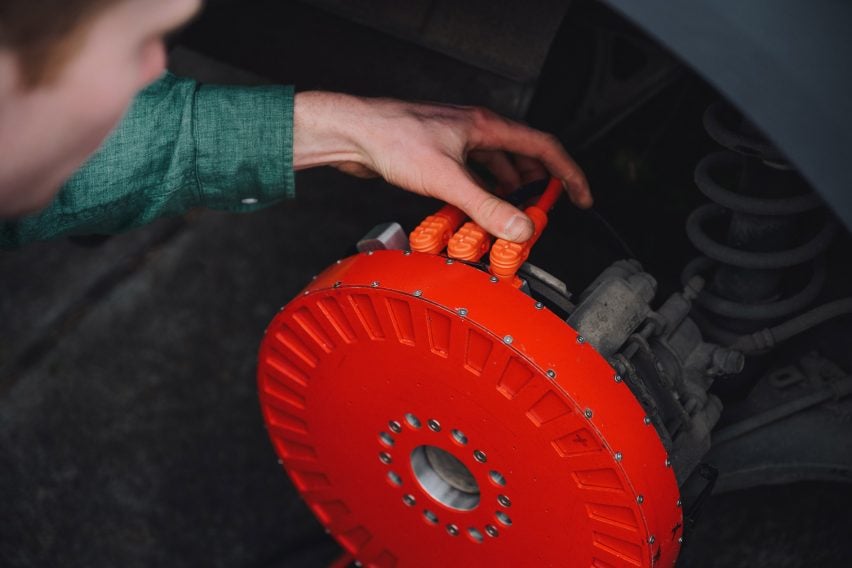

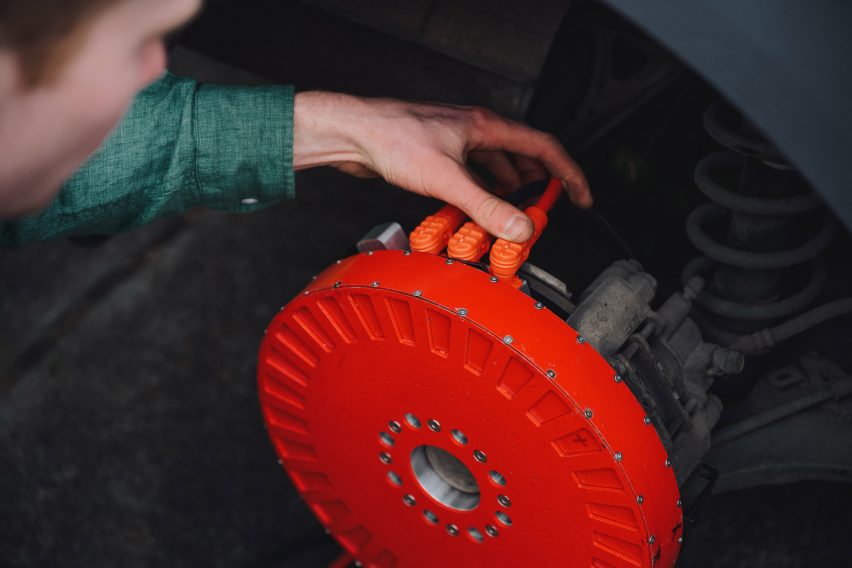

With REVR, those components are left untouched. Instead, a flat, compact, power-dense axial flux motor would be mounted between the car’s rear wheels and disc brakes, and a battery and controller system placed in the spare wheel well or boot.

Some additional off-the-shelf systems – brake and steering boosters, as well as e-heating and air conditioning – would also be added under the hood.

By taking this approach, Burton believes he’ll be able to offer the product for around AU$5,000 (£2,640) and make it compatible with virtually any car.

Burton is a bachelor’s student in industrial design and sustainable systems engineering at RMIT University in Melbourne but has worked on REVR largely outside of his course.

The spark for the project came a few years ago when he and his dad started thinking about converting the family car, a 2001 Toyota that Burton describes as well-built and reliable.

“But it’s just not really something you can do get done,” he told Dezeen. “It’s super expensive and it’s not really accessible.”

Burton wanted to find an affordable solution for others in his position while helping to reduce the emissions associated with burning petrol as well as manufacturing new electric vehicles, which are estimated to be even higher than for traditional cars.

With REVR, people should be able to get several more years of life out of their existing cars.

The kit would transform the vehicle into a hybrid rather than a fully electric vehicle, with a small battery giving the car 100 kilometres of electric range before the driver has to switch to the internal combustion engine.

However, in Burton’s view, this is where people can get “the most bang for their buck” with few changes to the car but major emissions reductions.

“You can’t fit a huge battery in a wheel well but we wager you won’t need one,” said Burton. “While people drive a lot, especially here in Australia, on average they drive 35 kilometres a day and it’s mostly commuting.”

“This distance would require only a five-kilowatt-hour battery, and we can put three times that in the wheel well.”

Burton used the motor modelling packages FEMM and MOTORXP to develop the design of his motor, which sees the spinning part, called the rotor, placed between a vehicle’s disc brakes.

The stationary part, or stator, is fixed to existing mounting points on the brake hub.

Borrowing a trick from existing hybrid vehicles, the kit uses a sensor to detect the position of the accelerator pedal to control both acceleration and braking.

That means no changes have to be made to the car’s hydraulic braking system, which Burton says “you don’t want to have to interrupt”.

While the design is in its early stages, the concept was advanced enough for the jury of the James Dyson Award for exceptional student design to pick the project as the national winner in Australia.

The international prize winner from the 30 included countries will be announced on October 18.

Burton plans to use the AU$8,800 winnings from the national award to buy a small CNC machine and the specialist materials that are required to build a working prototype, building on a previous non-working prototype made in RMIT’s workshop.

He says he has “a stretch goal” of converting a million cars with REVR and is interested in working with partners in the automotive industry. But he is also critical of its lack of investment in retrofitting to date.

“It’s like with repairability, industry is so against that,” Burton told Dezeen. “They love the whole planned obsolescence thing.”

“Ultimately, to retrofit goes against their profit margin because it extends the usefulness and the lifetime of their products. I think that’s why there’s retrofitting companies out there but they’re still largely reserved to classic cars. It’s just so expensive to do.”

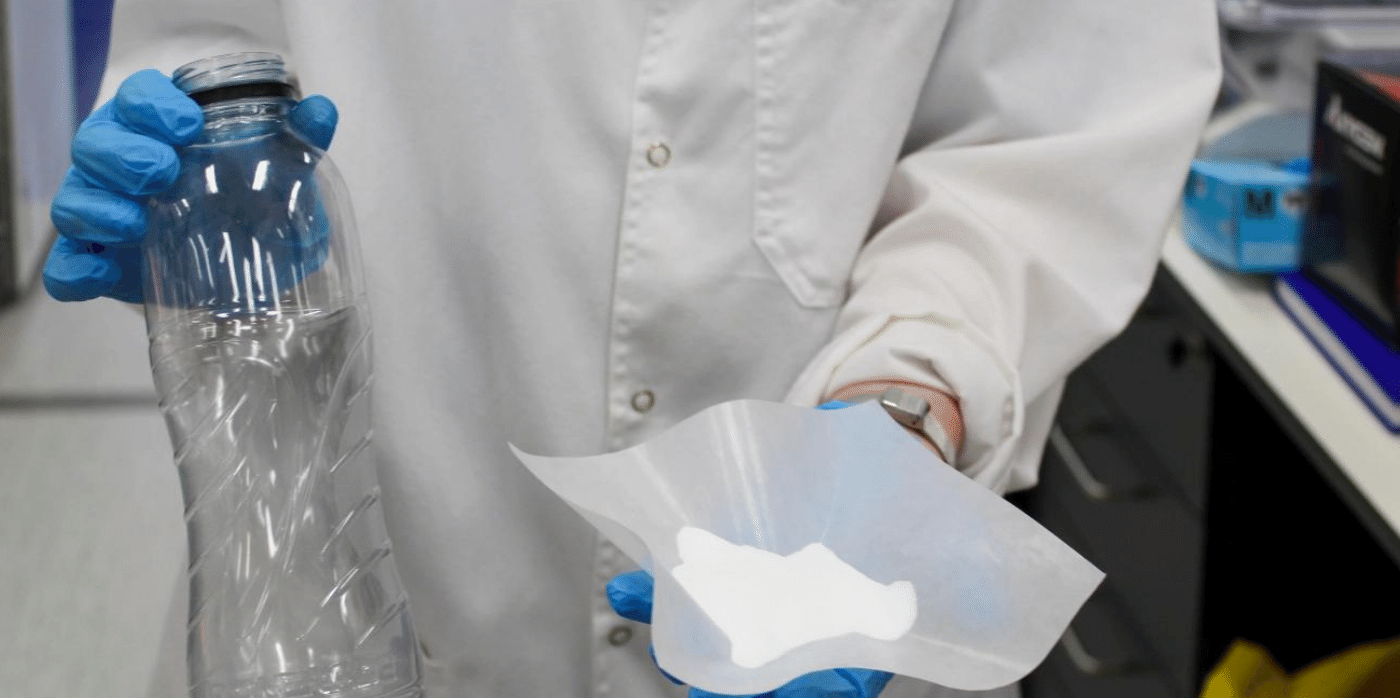

Previous winners of the James Dyson Award include an infection-sensing wound dressing created by students from the Warsaw University of Technology and a fish-waste bioplastic by British designer Lucy Hughes.