Food-waste dyes bring colour to mycelium leather by Sages and Osmose

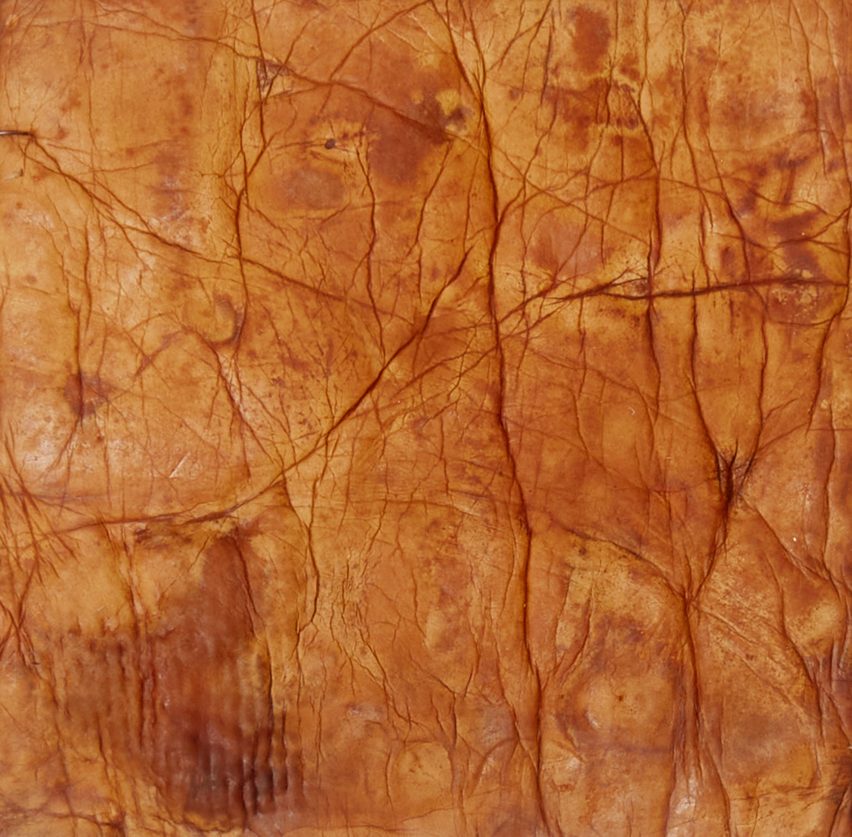

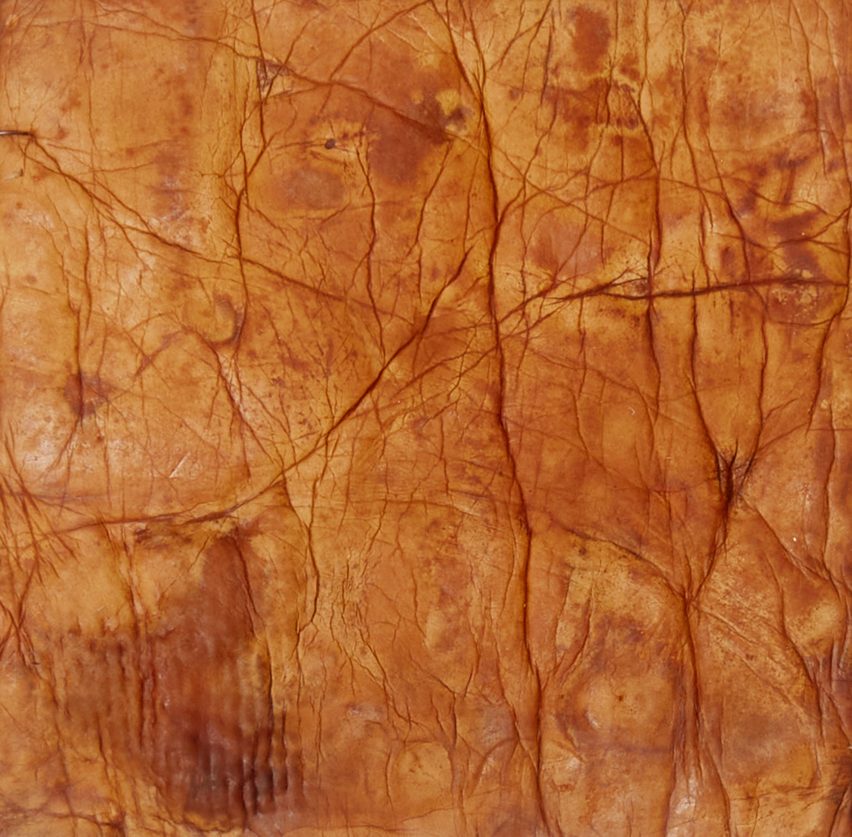

Two British materials companies, Sages and Osmose, have collaborated to dye sheets of mycelium with natural food waste, mimicking the appearance of tanned leather and suggesting a colourful future for the biomaterial.

Osmose is a company making a leather alternative from mycelium – the fibrous underground root network of mushrooms – while Sages makes natural dyes from food waste such as avocado pits, blueberries, red cabbages and onion skins, which are normally applied to textiles.

The two believe they’ve achieved a world first with their collaboration, combining two emerging areas of sustainable material development to colour mycelium without resorting to petroleum-based synthetic dyes, thereby keeping the product non-toxic and able to biodegrade safely in soil.

“There are lots of different types of vegan leather alternatives to traditional leather but the majority of them use either synthetic colourations or they use plasticisers, so they’re non-biodegradable,” said Sages CEO Emily Taylor.

“We wanted to explore an option where we could have a fully biodegradable leather that has also been coloured in a biodegradable and sustainable manner,” she continued.

Companies that prioritise biodegradability have offered mycelium in its natural shades of white and brown or black, which Osmose CEO Aurelie Fontan says is much easier to achieve naturally.

“I think the challenge for mycelium leather was that the offering just wasn’t there in terms of aesthetic,” she said. “When you’re presenting for brands and you’re like ‘we can only do brown’, it’s a little bit boring for them.”

“The colour sector is somewhere where you can develop your USP, essentially, which is why working with Sages is so interesting,” Fontan added.

Osmose and Sages have created tan-coloured mycelium sheets using avocado waste, which Sages sources from an importer and guacamole factory in Milton Keynes, where tens of tonnes of leftover pits and skins are produced each week.

It was a new area for both companies, as the food waste dye takes differently to mycelium leather than it does to the usually cellulose-based textiles that Sages has worked with.

The duo collaborated with materials science researchers at the UK’s Cranfield University on the project, for which the researchers focused on how to transfer and fix the dye to the material using “green chemistry” – an area of chemistry that aims to cut out hazardous substances.

In this case, the researchers sought to replace the formic acid and fluorinated acids that are often used in tanning to dissolve the polymers of the leather so it can be infused with dye. Instead, the team developed a method, which they say is significantly less toxic.

After working with Cranfield University, Sages and Osmose expanded the experiment and trialled other waste streams such as blueberries and onion skins to see what colours they could get, producing mycelium swatches in shades of violet and bordeaux.

Taylor and Fontan say they are trying to develop a process for mycelium that is akin to leather tanning, where both colour and durability properties are added in one or two steps. Their equivalent, they say, would be to dye and waterproof the material at the same time.

Osmose’s focus now is on developing a waterproof coating for their mycelium that, like the dye, is bio-based, non-toxic and able to biodegrade safely in soil. This is notoriously a challenge for plant-based leather alternatives, which almost always rely on a protective synthetic coating.

“It’s really hard to design a solution that fits all materials, which is basically what everyone is struggling with,” said Fontan. “Someone might have pineapple leather and they have their own coating but it doesn’t mean it’s going to work on mushroom and so on.”

Unlike some companies, however, Osmose says it does not want to bring a product with a non-biodegradable coating to market.

“If you’re doing a composite, it will not biodegrade at the end of life, which is compromising all the good work that you’ve been doing before that step,” Fontan said.

Mycelium is one of the most popular emerging leather alternatives. It has already appeared in luxury goods such as a bag by Hermes, clothing by Stella McCartney and trainers by Adidas.