Architizer’s new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.

COVID-19 has left many office buildings half-empty in city downtowns across the United States, and as vacancies rise, commercial property values drop. The demand for office space might not rebound to pre-pandemic levels as some observed have augured.

Banks, city governments and property management companies fear the severity of the situation and its potentially dismal economic consequences. At the same time, the housing shortage is becoming a major problem for many cities. Could empty office buildings be the remedy to the housing crisis? What does it take to convert office buildings into housing?

One would think that the idea of converting office buildings into residential would presumably face little-to-no opposition and be promoted by cities and planning authorities as a possibility to mitigate the housing shortage and activate districts. It could be a win-win situation if not for the red-tape bureaucracy — local building and zoning regulations — and the technical difficulties, including structural, energy/mechanical, accessibility and fire safety upgrades, among other requirements. These requirements limit the number of vacant office buildings that could potentially be converted into residential use.

Zoning Regulations

There is no general rule for turning office space into housing, and each building must comply with local building and zoning regulations. Zoning rules vary, but they often share the common purpose of separating occupancies — i.e. separating residential from commercial use. For this specific reason, it is difficult to change the use of an existing building, and developers wanting to undertake such a task will have to apply for a variance, which may face opposition before it is granted. Difficulties don’t end here. In addition to zoning regulations, building codes will influence redevelopment projects.

Generally, building codes applied to residential projects are considerably different from those that apply to office buildings. Adapting an existing structure to a new use will involve the cooperation of different agencies to address the complexities that come with the change of occupancy use. But given the extraordinary situation where on the one hand, we have thousands of vacant office square footage and, on the other hand, an urgent housing shortage, it would make perfect sense to relax these regulations and try to solve both problems. City authorities have in their hands the opportunity to make change recommendations in city zoning regulations. In this respect, New York’s Mayor Eric Adams has been encouraging modifications to zoning and building codes to spur the office-housing transformation.

8899 Beverly Boulevard by Olson Kundig, Los Angeles, California | Image by Nils Timm.

For the time being, zoning and building regulations make it hard for office buildings to be turned into a different use, especially into residential, simply because the requirements for one are so different from the other. Let’s look at some of the specific requirements to turn an office building into housing: Light and ventilation are perhaps the most critical factors that play into the equation.

Light and Ventilation Requirements

One crucial requirement is that habitable spaces need to be provided with a minimum amount of light and ventilation. Oddly, pre-air-conditioning-era office buildings are potentially better suited to office-to-housing transformation. Their size and configuration were dictated by the necessity to provide offices with light and ventilation. When air-conditioning and fluorescent lighting became characteristic features of the office environment, the narrow, rectangular footprint of the typical office building — and its U-, L-, C, and E-wing variations — could expand to larger floor plates filled with rows of offices that no longer needed a window close by. That is when things got complicated for the office-to-housing transformation. The distance from the center of the building to an exterior wall is often so great — even when the center is formed by a circulation and utility core — that it is impossible to create an effective layout where all the units have windows.

Adding to this problem is the type of building envelope. The interiors of modern office buildings are, for the most part, sealed behind curtain walls. To comply with the light and ventilation rule required in residential buildings, the entire glass skin needs to be replaced with a system that incorporates operable windows.

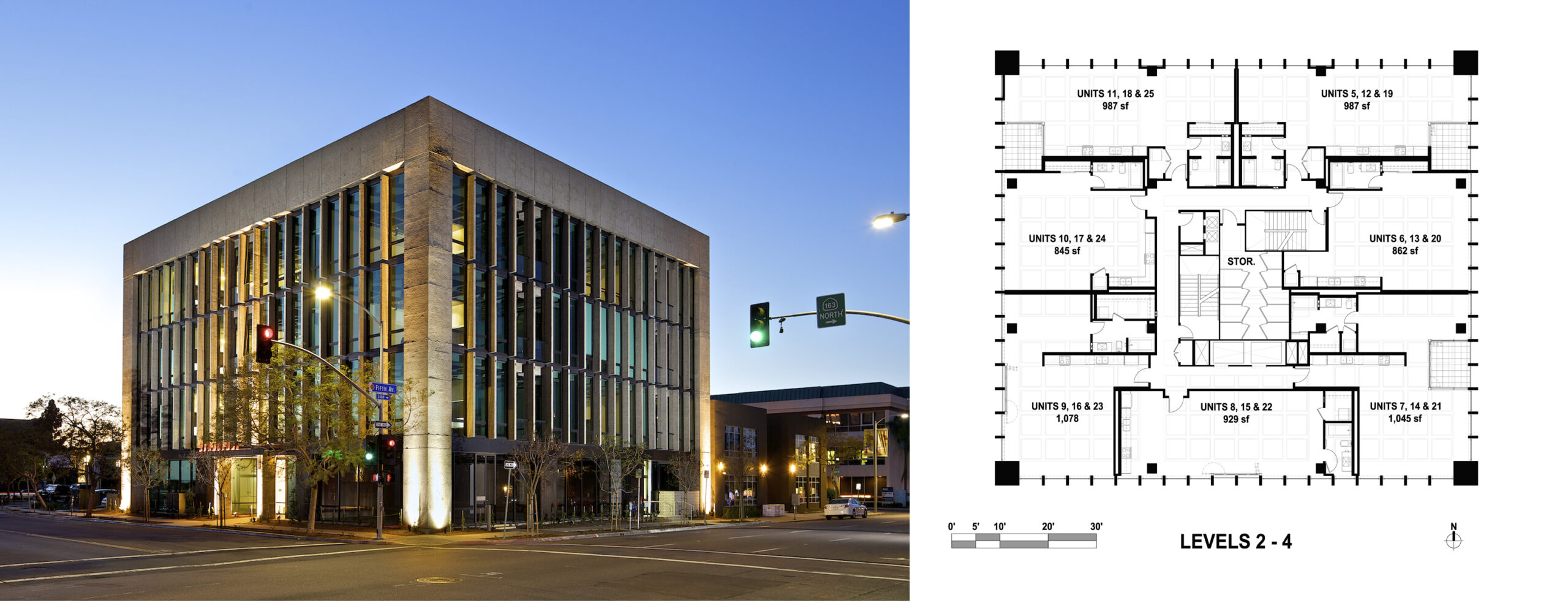

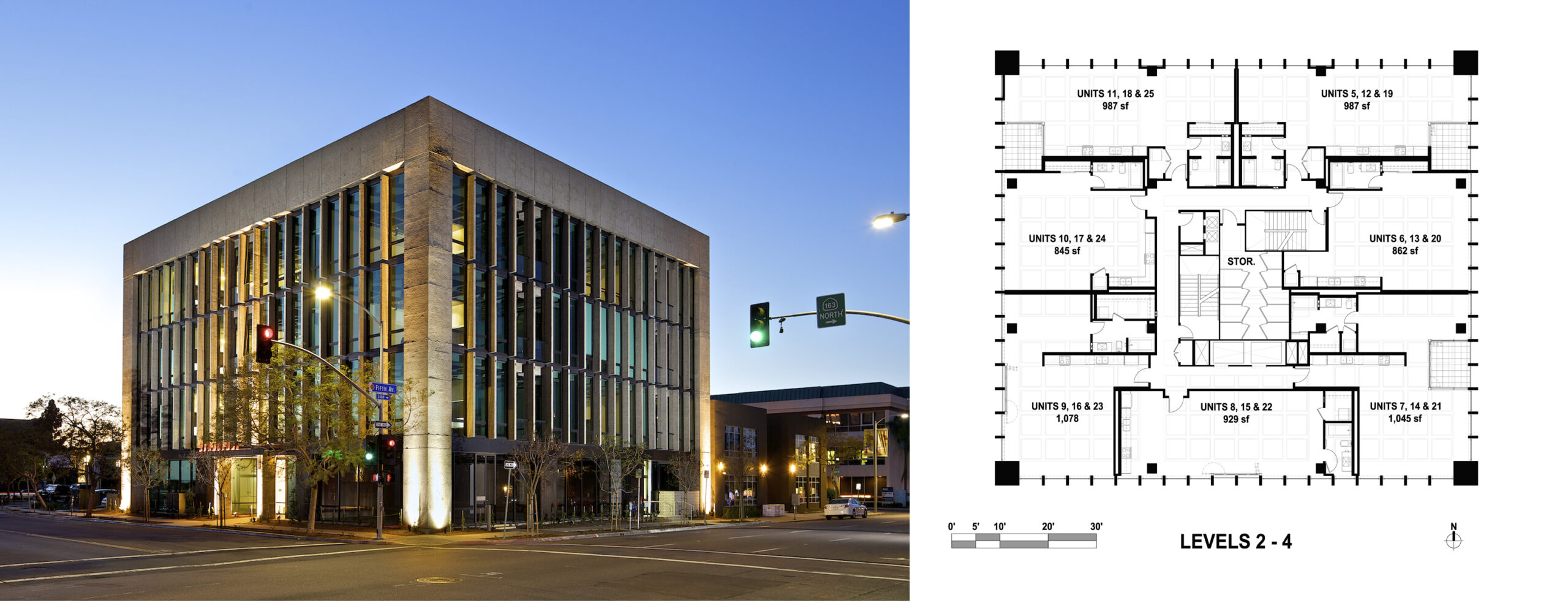

The Structure Lofts by H2 | Hawkins + Hawkins Architects, Inc. San Diego, California | Image by Brent Haywood.

Other factors, including the configuration of the structural grid and the window location, impact the viability of office-to-housing conversion projects and dictate the layout and size of the rooms in new apartments. Above, the Hawkins + Hawkins Architcts‘ office building-turned-apartment complex shows the typical floor plan for all levels above the ground floor with units around a circulation and storage central core. The open plan of all the units allows for natural light to reach every corner.

The design reimagines a four-story, modern office building that served as San Diego’s Blood Bank for nearly 40 years. Offering panoramic views of the city skyline, a central park and a bay, the building inspired the conversion to loft apartments. The goal was to create expansive, energy-efficient living units through adaptive reuse while preserving a landmark. The interior structural elements such as the concrete floors and coffered ceilings, were exposed to create a clean, industrial look. Single-glazed windows were replaced with energy-efficient, dual-glazed, floor-to-ceiling vinyl windows; and new, energy-efficient mechanical and electrical systems were installed.

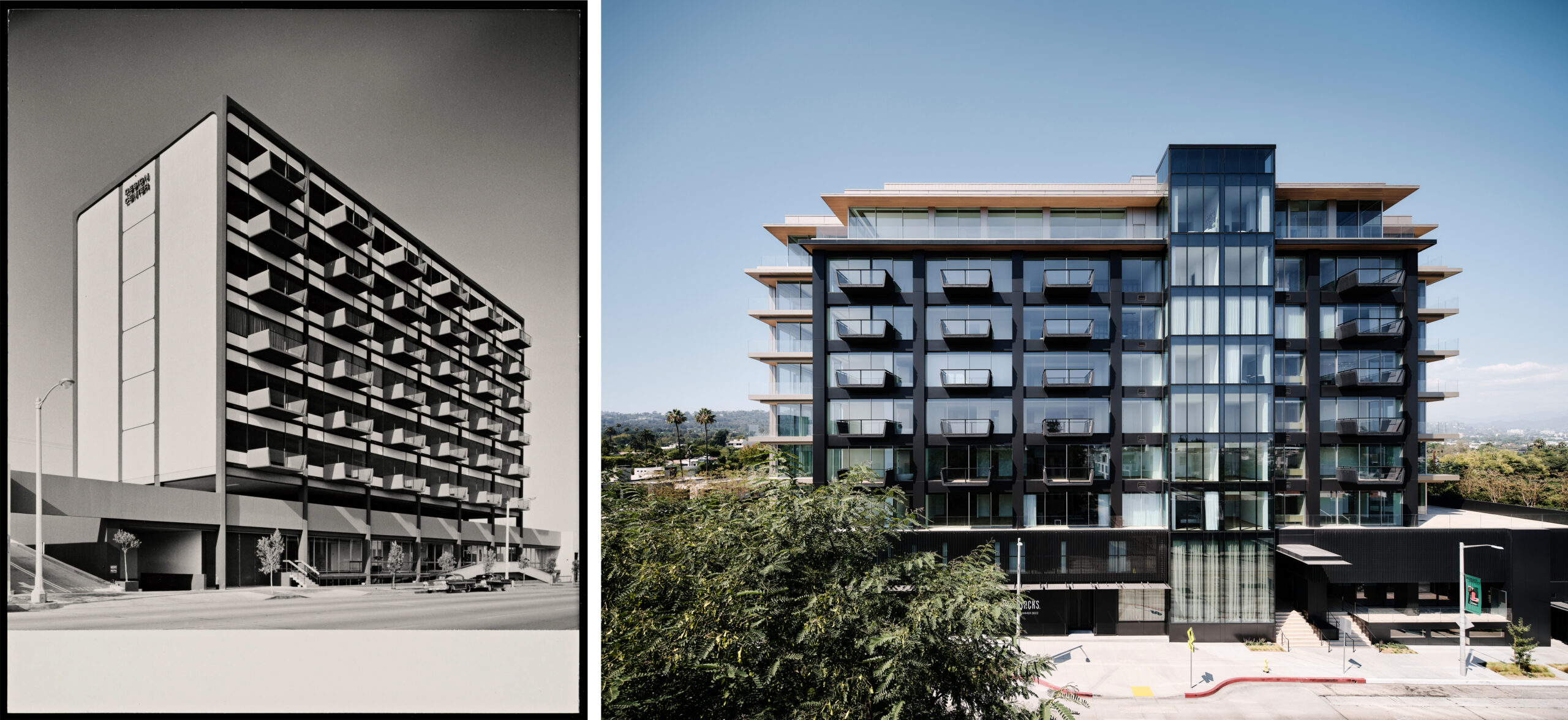

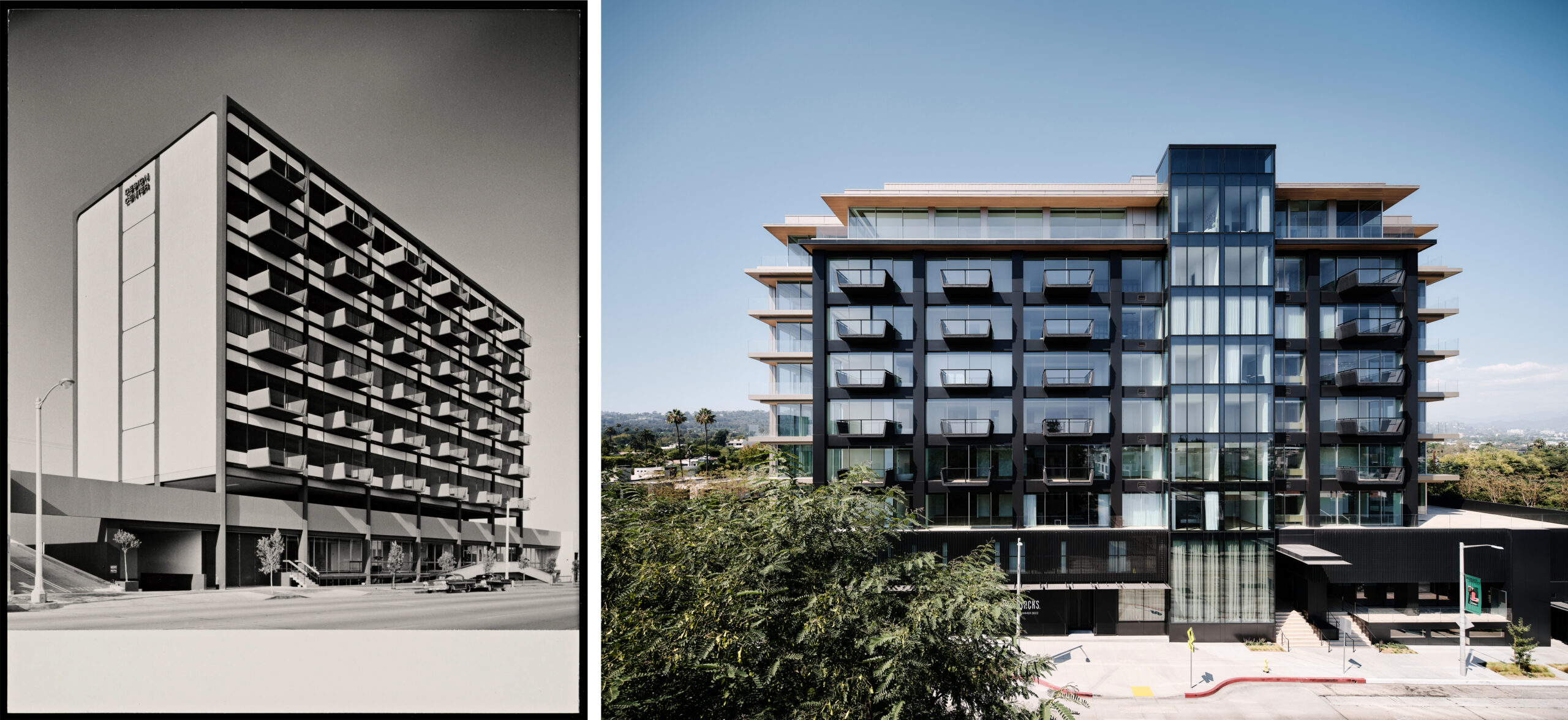

The International Design Center, originally designed by Richard Dorman in 1964 (left) and 8899 Beverly Boulevard by Olson Kundig, Los Angeles, California | Image by Joe Fletcher (right).

8899 Beverly Boulevard by Olson Kundig, Los Angeles, California| Images by Joe Fletcher.

Here is another office-to-housing redevelopment example. The International Design Center, originally designed by Richard Dorman in 1964, is located in today’s heart of West Hollywood’s vibrant arts and design district in Los Angeles. Olson Kundig‘s redevelopment design maintains the building’s original integrity while transitioning its function to a 48-unit luxury condo complex.New additions are set back from the structure to acknowledge the building’s form. The upper levels contain a mixture of one-, two-, three- and four-bedroom units, fifteen of which are designated market rate. Private amenities on the lower level include a residential lobby, fitness room and an adjacent pool area. The building’s new design highlights indoor-outdoor connections through a generous use of glass while maintaining the building’s original concrete balconies. The updated façade incorporates a shutter system to control shade and privacy. Roof terraces on the new penthouse level extend livable areas outdoors, opening to views of West Hollywood and the Hollywood Hills beyond.

Are Large Office Buildings Doomed?

8899 Beverly Boulevard by Olson Kundig, Los Angeles, California | Images by Joe Fletcher.

The way office buildings are designed factors in the suitability for office-to-housing transformation, and for now, large office buildings offer a hornet nest of unsolvable technical difficulties after factoring in cost, profitability and physical limitations. The amendment of local zoning and building regulations is critical to facilitate the redevelopment of offices into homes. In the most extravagant — and extraordinarily expensive — cases, developers can allow their imagination to run wild: carve out portions of a building to create outdoor terraces that bring light and air into otherwise windowless apartments or blow up holes in the floor plates to run lightwells. Mix-use occupancy could be an option worth exploring. In this case, fire separation and exits would be challenging issues that would need to be addressed.

Office-to-housing redevelopment costs can be exorbitant, and most certainly, such projects would only be viable when offered as luxury apartment buildings. At this rate, the office-to-housing redevelopment projects will probably have little positive impact on the housing shortage, at least for now. Code relaxation and economic incentives to allow these conversions to take off are urgently needed.

Architizer’s new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.