Buildings “biggest lever” for improving global resource efficiency says UN

The built environment is the fastest-growing consumer of materials in the world – but it also offers the most potential for improvement according to Julia Okatz, advisor on the UN’s landmark Global Resource Outlook.

Making buildings and neighbourhoods more efficient could reduce the global need for raw materials by 25 per cent by 2060, the International Resource Panel (IRP) report found, while slashing energy demand and emissions by 30 per cent.

“Built environment patterns are the single most important determiner of a country’s emissions,” Okatz told Dezeen.

“[Firstly] because of its direct impacts, because of heating and all the climate impacts embodied in materials, but also because of its impact on people’s behaviour,” she continued.

“The built environment isn’t just concrete use, it has all these other implications on energy use, so it is probably the biggest lever overall.”

The need for carefully considered buildings that reduce resource use while maintaining or even improving inhabitants’ quality of life presents an exciting opportunity for architects to take more control of the planning process, Okatz argues,

“I think architects would be one of the major benefitting industries in this scenario,” she said.

“We need less mass deployment of inefficient options and much more architectural design. So I think for architects, it’s actually a growth agenda.”

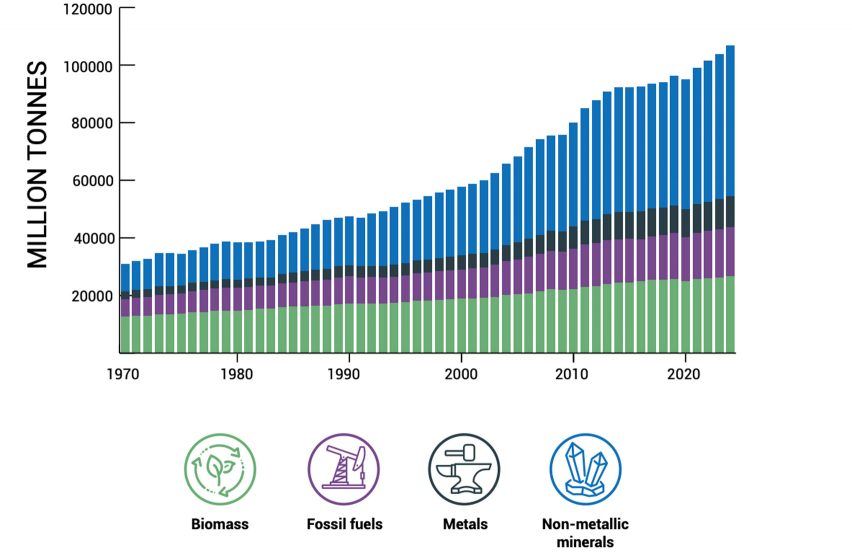

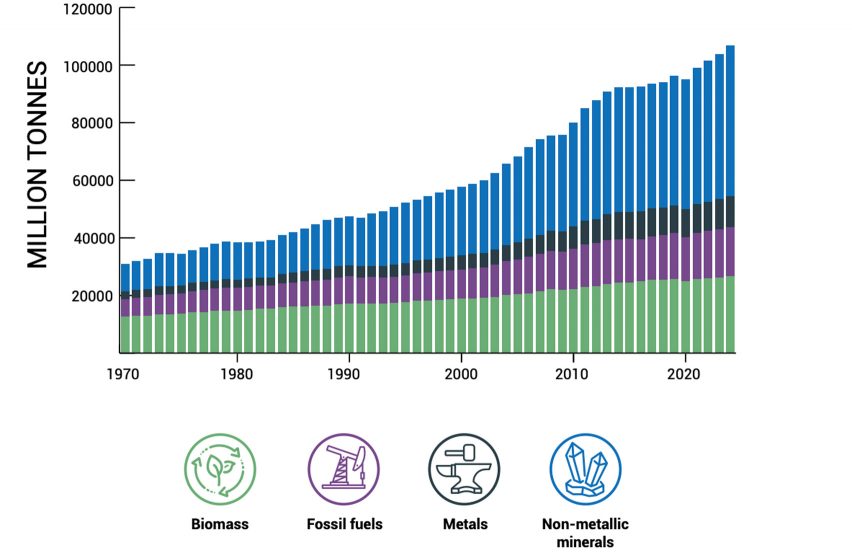

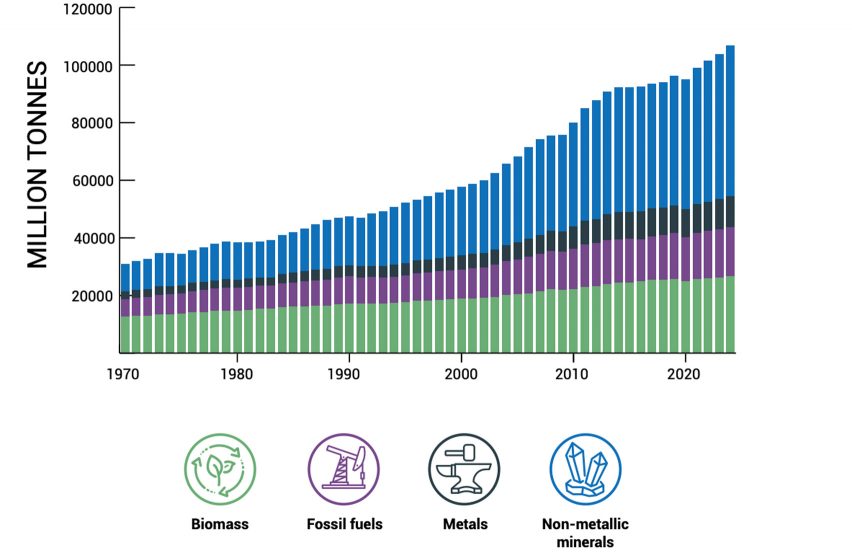

Resource use tripled in the last 50 years

Launched during the sixth session of the UN Environment Assembly this month, the 2024 Global Resource Outlook is the IRP‘s latest review of the world’s resource use since the last edition of the report was published in 2019.

Our “insatiable use of resources” has tripled over the last 50 years, the latest report found, and is now responsible for over 55 per cent of global emissions and 40 per cent of air pollution impacts, making it the “main driver” of the planetary crisis.

While environmental impacts are escalating, the economic and wellbeing benefits brought by our increasing use of the Earth’s resources have stagnated – and in some cases even declined

Left unchecked, material extraction looks set to rise by a further 60 per cent by 2060, compounding these negative impacts.

Buildings and construction are chief among the four sectors responsible for this increase, according to the Global Resource Outlook. “The built environment globally is the fastest growing material consumer,” said Okatz, who is the “right hand” of IRP co-chair Janez Potočnik and the director of natural resources at consulting firm Systemiq.

But the report also outlines an achievable path by which the industry could reduce its use of raw materials by 25 per cent by 2060, while helping to deliver “global prosperity”.

“You can lift a lot of those people now living in poverty onto a level of really good quality of life in a really efficient way if – and this is the important if – high-income countries also get a lot more efficient,” Okatz said.

Single-family homes “bad urban design”

Concrete makes up the biggest and fastest-growing chunk of the built environment’s material demand.

Sand, gravel, limestone and other “non-metallic minerals” used to make concrete account for half of all materials extracted globally and around half of the industry’s entire climate footprint, according to the Global Resource Outlook.

More efficient structural design – making use of innovations such as vaulted flooring and clever formwork – can reduce concrete use per building by around 30 per cent, Okatz estimates.

And switching to low-carbon concrete or biomass-based alternatives like timber can help to mitigate some of the adverse environmental impacts.

But perhaps the biggest and most undervalued solution highlighted in the report lies in changing what kind of buildings are built – not just how they are constructed, according to Okatz.

“About 50 per cent of residential construction in Europe is single-family homes and, to be honest, that’s just bad urban design,” she said.

“It’s also not particularly future-proof because demand might still be quite high now but the overall trend, largely, is people moving into city centres and wanting to be less car-dependent,” she added.

“So we think a lot of that will basically be a bad investment beyond 20 years from now, even if it wasn’t resource inefficient.”

Architects can lead the charge

Instead, the data suggests we need more “medium-density” residential buildings, which require fewer resources to build and operate while offering a superior quality of life compared to more dense developments.

“In a European context, the average is to say something like six-unit houses are probably best,” Okatz said. “Because it still allows people really good green space access and good noise insulation, all of these things. But it’s quite efficient.”

Following the example of Belgium’s De Sijs project (top image) and Virrey Aviles Street housing in Buenos Aires (below), making these kinds of dwellings more aspirational and attractive presents a key opportunity for architects, according to Okatz.

“Architects and great design should be valued more because everyone can do a boring single-family home but not everyone can do an amazing six-unit community living space,” she said.

“What good architecture can do to slightly denser living – to me that is where I would see architects really leading the way,” Okatz continued.

“To say: if you do it right, this is how amazing life can be in these kinds of set-ups so people don’t even want to live in their own little thing anymore because it’s lonely, inefficient and expensive.”

The top image of the De Sijs housing project in Belgium is by Stijn Bollaert.