Colour-changing facade material could help to heat and cool buildings

Researchers from the University of Chicago have invented a cladding material that changes colour to help with heating or cooling and could be retrofitted to improve buildings’ energy efficiency.

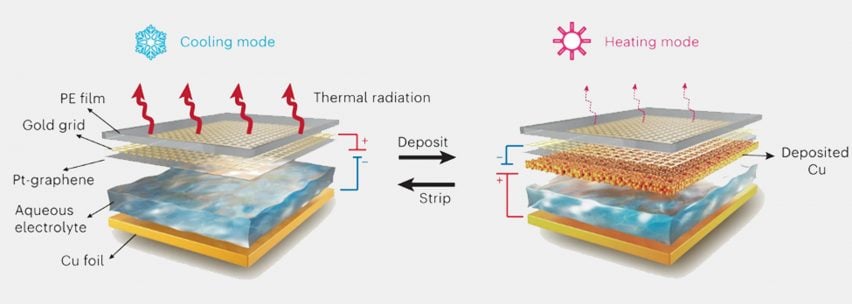

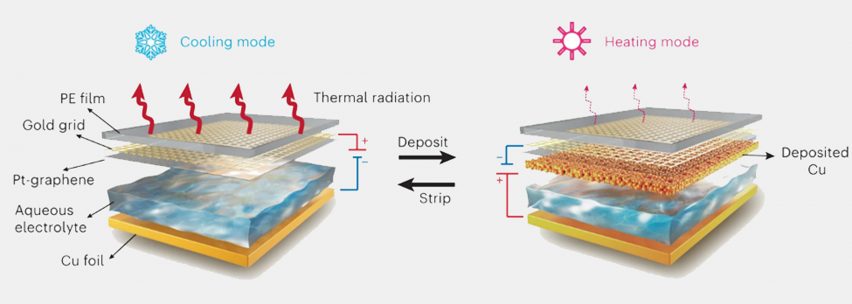

The composite material consists of several different layers including copper foil, plastic and graphene, and based on the outside temperature can change its infrared colour – the colour it appears under thermal imaging.

At the same time, it also changes the amount of infrared heat it absorbs or emits from the building. On hot days, the material appears yellow under thermal imaging, indicating that it is emitting more heat, while on cold days it appears purple because it is retaining that heat.

When used on a facade – for example in the form of shingles – the material could potentially reduce the need for heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) and lower a building’s overall energy consumption.

“We’ve essentially figured out a low-energy way to treat a building like a person; you add a layer when you’re cold and take off a layer when you’re hot,” said materials engineer Po-Chun Hsu from the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, who led the research.

“This kind of smart material lets us maintain the temperature in a building without huge amounts of energy.”

Cladding responds to temperature like a chameleon

The University of Chicago describes the material as “chameleon-like” because it can change its colour in response to the outside temperature.

At a chosen trigger temperature, the material uses a tiny amount of electricity to either deposit copper onto a thin film or strip it away.

This chemical reaction effectively transforms the material’s central layer – a water-based electrolyte solution – into solid copper. The low-emitting copper helps to retain heat and warm the interior of a building, while the high-emitting aqueous layer keeps a building cool.

The layer of water-based electrolytes also helps to make the material non-flammable, and the researchers describe the switching process from metal to liquid and back again as “stable, non-volatile, efficient and mechanically flexible”.

“Once you switch between states, you don’t need to apply any more energy to stay in either state,” said Hsu. “So for buildings where you don’t need to switch between these states very frequently, it’s really using a very negligible amount of electricity.”

Material could reduce energy consumption by eight per cent

As part of their study, published in the journal Nature Sustainability, the researchers also created models to test the energy savings that could be achieved by applying their material to buildings in 15 US cities, representing 15 climate zones.

In areas that experienced a high variation in weather, they found the material could save 8.4 per cent of a building’s annual HVAC energy consumption on average. At the same time, the material relied on just 0.2 per cent of the building’s total electricity for its operation.

As it stands, building construction and operations account for nearly 37 per cent of global carbon emissions, most of which is attributed to building operations including lighting, heating and cooling.

To slash these emissions, the material could be used to retrofit poorly insulated or historic buildings and improve their energy efficiency, as the researchers suggest it would be more convenient to install than insulation.

However, several of its components – including the monolayer graphene and gold microgrid used as transparent conductive layers – are currently still expensive and complicated to manufacture.

The researchers have so far created only six-centimetre-wide patches of the material but imagine assembling them like shingles to form larger sheets.

With the watery layer active, the material is a dark white colour, which turns a coppery brown when the copper layer is active.

But the material could also be tweaked to show different colours by adding a layer of pigments behind the transparent watery layer.

Another approach to keeping buildings cool is to paint them white. For this purpose, researchers at Purdue University recently developed the “whitest paint on record”, which reflects 98 per cent of sunlight.

Images courtesy of Hsu Group.