Mexico City community centre has blue-tinted concrete walls

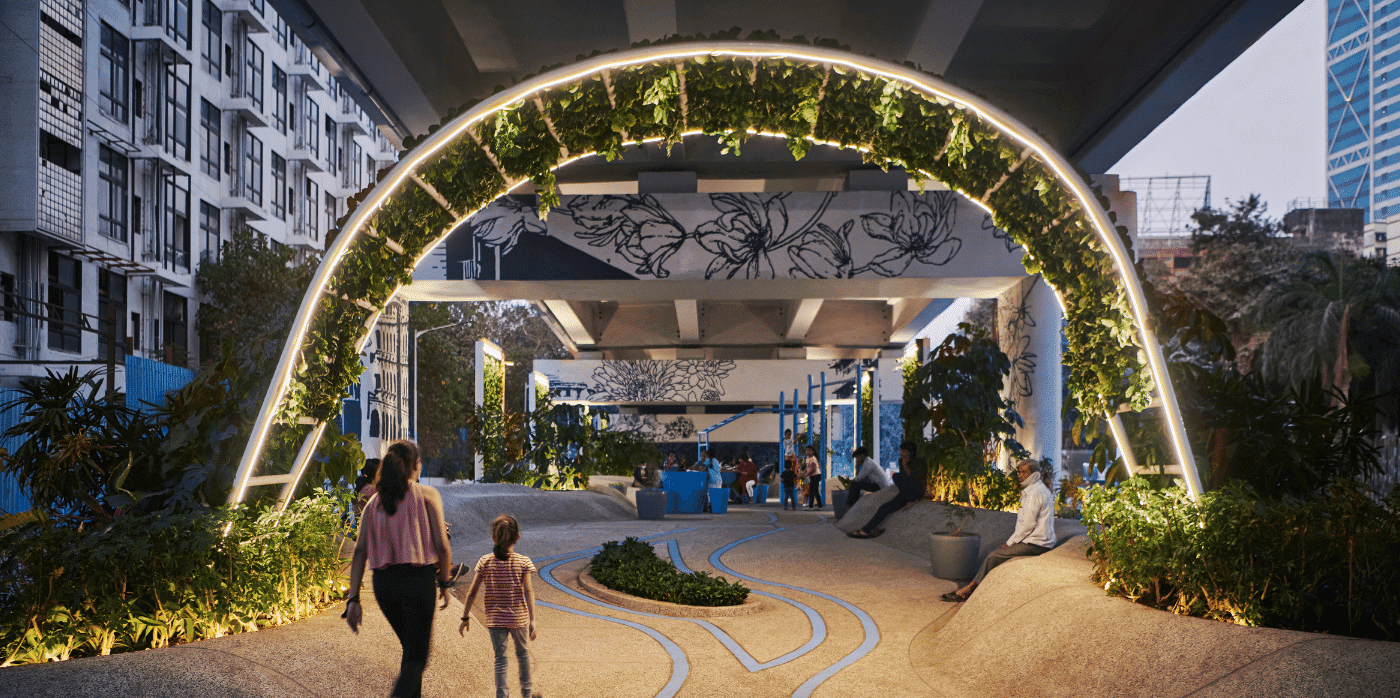

Design firms WORKac and Ignacio Urquiza Architects have created a multi-level, concrete community centre in an underserved neighbourhood that is meant to “promote the regeneration of social life”.

The building by New York’s WORKac and local studio Ignacio Urquiza Arquitectos – officially called PILARES Lomas de Becerra — is located in a hilly area and rises up from a dense intersection surrounded by active streets.

Located in Mexico City’s Lomas de Becerra neighbourhood, the building was created as part of a government initiative called PILARES, which stands for Points of Innovation, Freedom, Art, Education and Knowledge.

For a slender, irregularly shaped site, the team devised a multi-storey facility that encompasses 5,059 square feet (470 square metres).

“In appearance, the volume is simple and compact, with a strong character that confirms its presence as a public building,” the team said.

Walls are made of concrete – a material chosen for its construction and structural efficiencies, as well as its thermal and aesthetic qualities, the team said. The concrete was dyed blue, a decision informed by the vibrant colours found in the surrounding area.

Launched in 2018, the PILARES programme aims to create opportunities for residents in underserved areas.

“Each PILARES building is designed to support various kinds of classes and workshops in support of skill building, as well as bringing cultural programming, learning opportunities, and safe spaces for leisure and cross-generational gathering to each neighbourhood,” said New York’s WORKac.

“The sites selected for their construction create new landmarks in the urban fabric, enabling the population to identify them as community meeting centres that promote the regeneration of social life.”

Mexico City’s government enlisted local and international design studios to create 26 facilities under the programme.

Buildings are meant to respond to the local context and follow programming guidelines developed through extensive community engagement.

The team tried to reflect the community and its values in the architecture.

“The use of colour in Mexican architecture is an element that has been transformed and reinterpreted in the hands of many artists and architects across generations,” the team said.

The building is fronted by a plaza that is shaded by pre-existing trees.

Part of the ground floor is sliced away to form an angled, glazed entry wall, which helps “the transition between exterior and interior spaces”, the team said.

“The diagonal opening on the ground floor provides clear and free-flowing pedestrian routes in every direction, inviting users to walk around the plaza and enter the building,” the team said.

Inside, the building contains three split levels, all of which are connected by a central staircase. Rooms are designed to be fluid and adaptable.

“This flexible approach leaves open the possibility for changes to the programme over the lifetime of the building and allows it to freely evolve and adapt,” the team said.

WORKac and Ignacio Urquiza Architects have designed a second PILARES building, in the borough of Azcapotzalco, that follows a similar design vocabulary.

Other PILARES buildings include a community centre in Iztapalapa by Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura that features a series of bridges, walkways and exterior staircases.

The photography is by Arturo Arrieta and Ramiro del Carpio.

Project credits:

Architect: WORKac and Ignacio Urquiza Architects (IUA)

Team: Amale Andraos, Dan Wood, Ignacio Urquiza Seoane, Michela Lostia di Santa Sofía, Eder Hernández, María del Mar Carballo, Ana Laura Ochoa, Anet Carmona, Noé García, León Chávez, Fernando Tueme, Sacha Bourgarel

Interior design and lighting: WORKac, IUA and APDA

Structure and engineering: BVG (César Barquera, Eduardo Barquera); Ecomadi

Landscape: Genfor Landscaping (Tanya Eguiluz)

Development: Mexico City government and ZV Studio (Carlos Zedillo)

Digital visualizations: Israel Levy

Client: Mexico City government

The first Long Beach library was founded in 1896 in a room adjoining the City Council office. Three years later the library moved into City Hall next to Pacific Park, and in 1909, a new Carnegie library opened near the location of the present Main Library. In 1915 Pacific Park was renamed Lincoln Park.

The first Long Beach library was founded in 1896 in a room adjoining the City Council office. Three years later the library moved into City Hall next to Pacific Park, and in 1909, a new Carnegie library opened near the location of the present Main Library. In 1915 Pacific Park was renamed Lincoln Park.

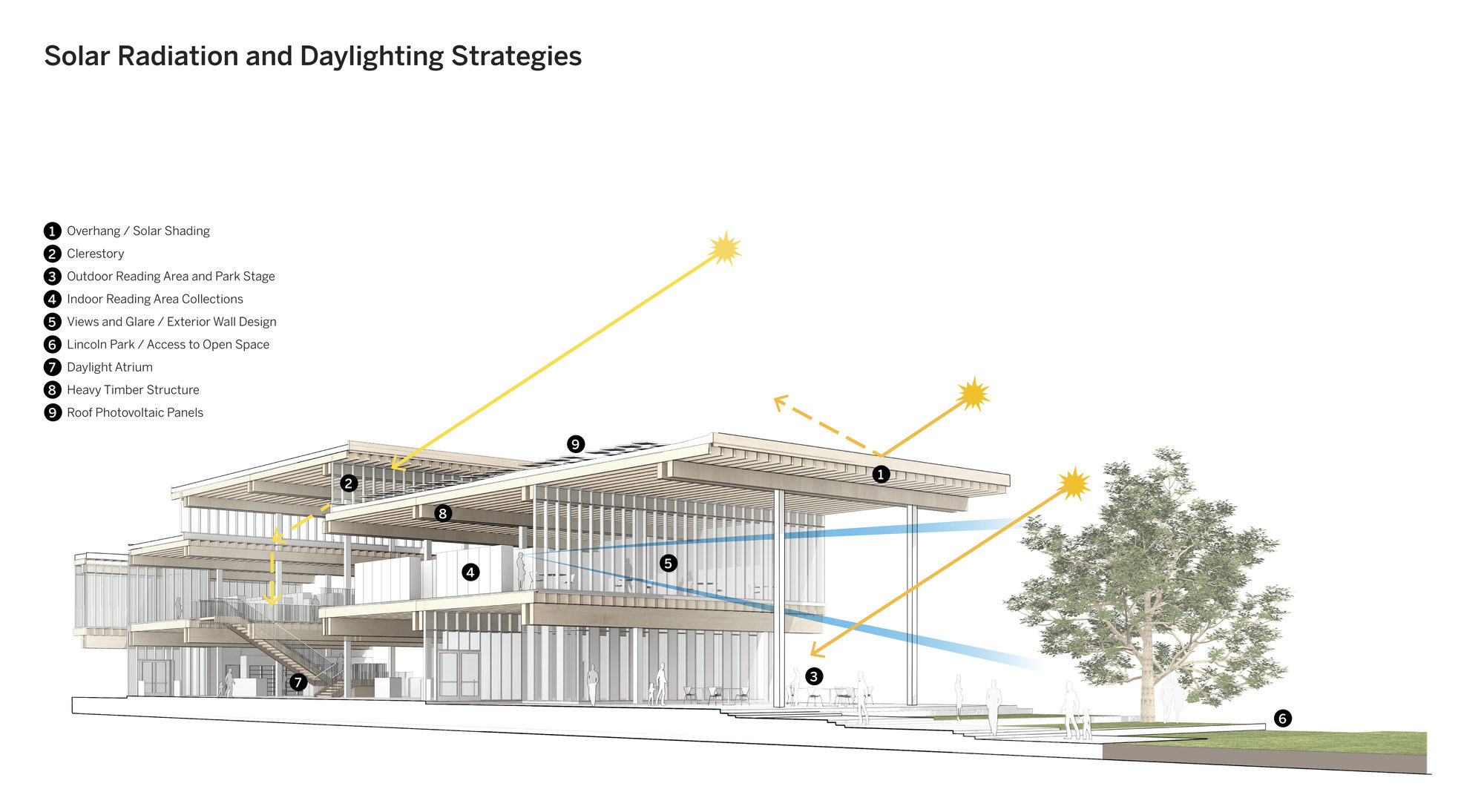

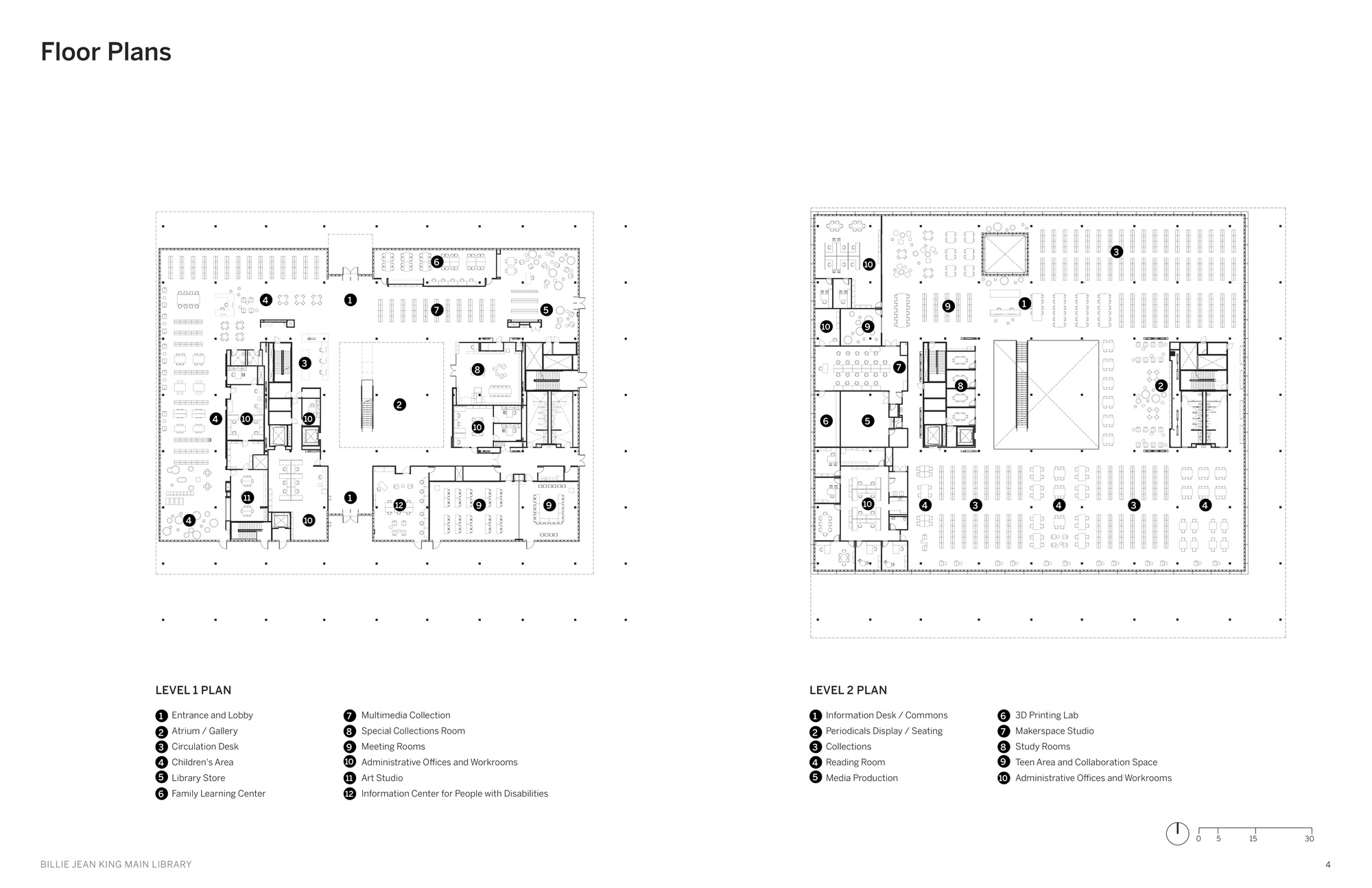

With its name that pays homage to the famed athlete and Long Beach native, the Billie Jean King Main Library is adjacent to Lincoln Park, a local landmark. The library was imagined as a pavilion within the new park, welcoming people inside from all parts of the city. It was made to serve as a traditional library and a modern, technology-focused hub for the community. SOM outlines that while there was a tight budget, the open interiors incorporate multi-use, flexible spaces that allow visitors of all ages to participate in solo and collaborative activities.

With its name that pays homage to the famed athlete and Long Beach native, the Billie Jean King Main Library is adjacent to Lincoln Park, a local landmark. The library was imagined as a pavilion within the new park, welcoming people inside from all parts of the city. It was made to serve as a traditional library and a modern, technology-focused hub for the community. SOM outlines that while there was a tight budget, the open interiors incorporate multi-use, flexible spaces that allow visitors of all ages to participate in solo and collaborative activities. The library offers a rich program of activities, in which reading and browsing book stacks are only a part of the experience. For instance, the main level features sizeable open spaces dedicated to children’s literature and activities organized by age. Each space is designed for social interaction, play and learning, while computers, book collections and quiet reading areas are available for use on the second level.

The library offers a rich program of activities, in which reading and browsing book stacks are only a part of the experience. For instance, the main level features sizeable open spaces dedicated to children’s literature and activities organized by age. Each space is designed for social interaction, play and learning, while computers, book collections and quiet reading areas are available for use on the second level.

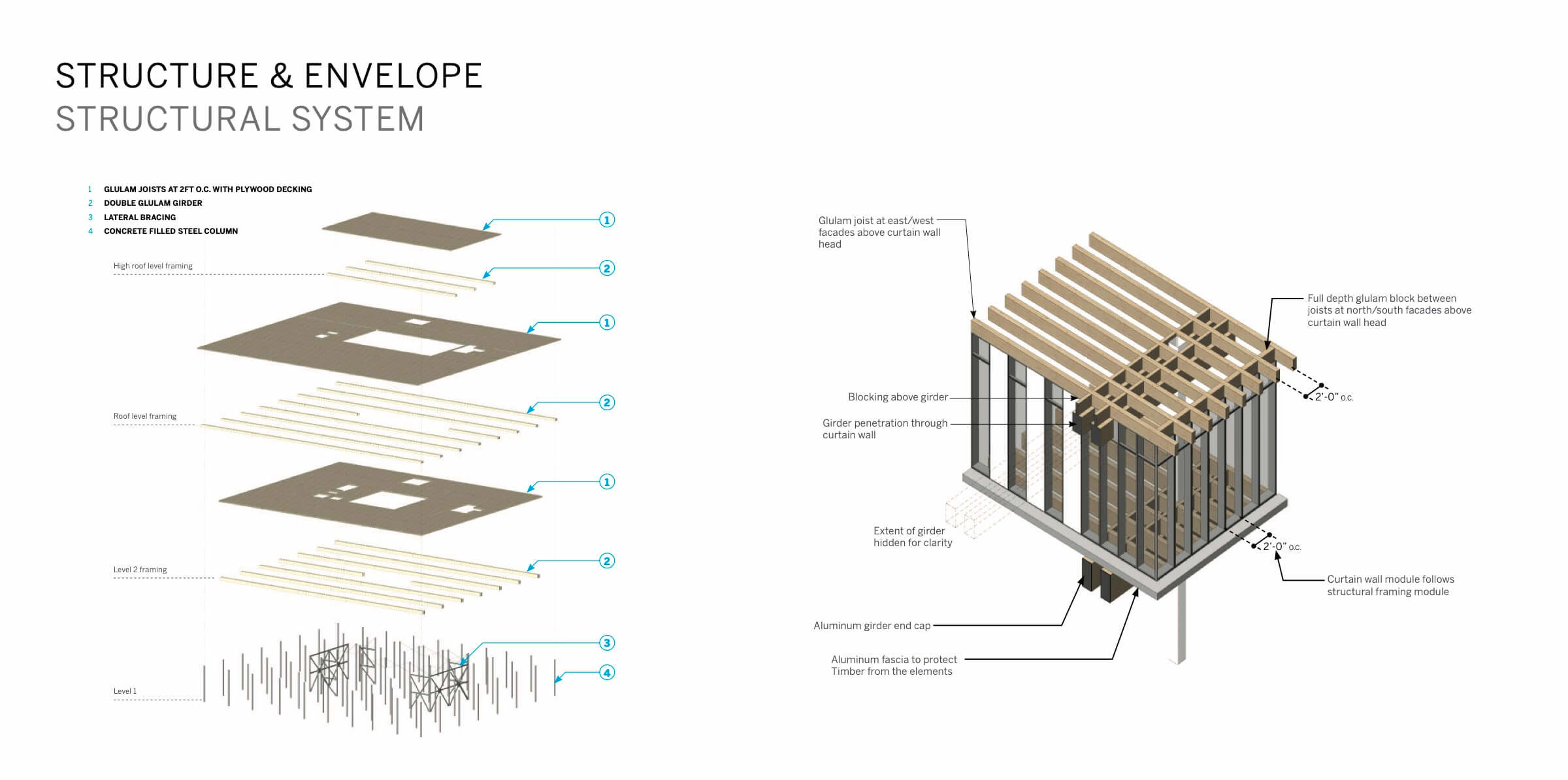

The building is one of the few in Southern California that utilizes a heavy timber structural system, composed of renewable timber reinforced with steel and concrete where needed. Each material is employed in a hybrid system to optimize its respective properties. The library’s superstructure consists of glue-laminated timber girders and joists with plywood decking, highlighting the warmth and character of the building.

The building is one of the few in Southern California that utilizes a heavy timber structural system, composed of renewable timber reinforced with steel and concrete where needed. Each material is employed in a hybrid system to optimize its respective properties. The library’s superstructure consists of glue-laminated timber girders and joists with plywood decking, highlighting the warmth and character of the building.

By using timber, a lightweight material, the library could be built atop the existing structure of an underground concrete parking garage. Saving most of the extant concrete structure also allowed the design team to significantly cut down on material waste; the design reduces embodied carbon by 61 percent, compared with erecting a new parking garage and a conventional concrete building. “Our goal was to leverage the power of clear ideas, natural materials, and Southern California sunlight to create a bright, beautiful, and beloved new place for the people of Long Beach” noted Paul Danna, Design Partner.

By using timber, a lightweight material, the library could be built atop the existing structure of an underground concrete parking garage. Saving most of the extant concrete structure also allowed the design team to significantly cut down on material waste; the design reduces embodied carbon by 61 percent, compared with erecting a new parking garage and a conventional concrete building. “Our goal was to leverage the power of clear ideas, natural materials, and Southern California sunlight to create a bright, beautiful, and beloved new place for the people of Long Beach” noted Paul Danna, Design Partner. After its completion, the Billie Jean King Main Library received LEED Platinum certification. The Library also won the Gold Award for the Best Social Infrastructure Project in 2016 and the Excellent Structural Engineering Excellence Award from the Southern California Structural Engineers Association in 2020.

After its completion, the Billie Jean King Main Library received LEED Platinum certification. The Library also won the Gold Award for the Best Social Infrastructure Project in 2016 and the Excellent Structural Engineering Excellence Award from the Southern California Structural Engineers Association in 2020.