Embodied Carbon: Reduce Your Home’s Hidden Carbon Footprint

Operational carbon is usually what we think of when energy costs are discussed. That is, carbon emissions that come from the energy used to power our homes, cars, etc. over their lifetime. Your home’s energy efficiency comes into play here. Generally, operational carbon emissions can be modeled and predicted, so you can compare one appliance or building product against another. Often, a label will show how much energy a certain appliance is likely to draw over a lifetime of operation, or how much a well insulated house will reduce your energy needs annually. But embodied carbon takes this modeling to a whole ’nother level.

Embodied carbon is the carbon footprint of a product, process, or service starting with the extraction of raw materials through the manufacturing process to market (cradle to gate) and then beyond to delivery and installation (cradle to site). Operational carbon is often considered separately, but adding the carbon embodied in a product’s end-of-life disposal (cradle to grave) or reuse or recycling (cradle-to-cradle) gives a complete lifecycle analysis. In other words, embodied carbon represents the total amount of greenhouse gases (including CO2) emitted during extraction, transportation, manufacture, delivery and deployment, and then end-of-life. Looking at both the embodied carbon and the operational carbon give you the true “carbon cost” of your product or project.

Let’s picture a new countertop for your kitchen. The embodied carbon of that countertop that you will enjoy in your home comprises the energy that goes into mining the stone, transporting the raw material from the mine to a facility for processing, its processing and preparation (cutting, strengthening, and polishing), transporting to a wholesaler, and then to your home where we include the energy emissions of cutting to size and setting it up in your kitchen. And finally its end-of-life, which hopefully includes reuse or recycling wherever possible.

Embodied carbon hides in your home

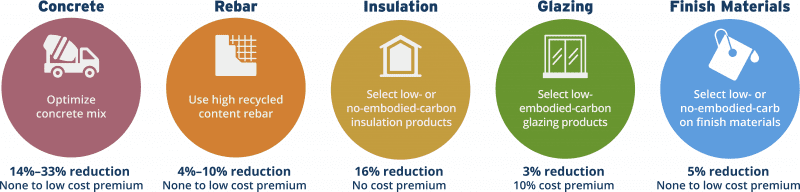

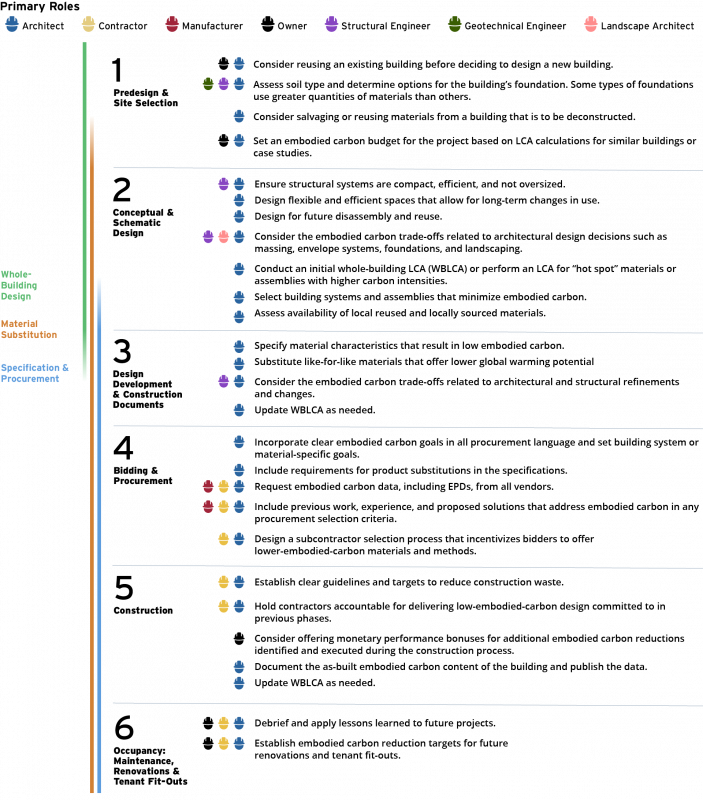

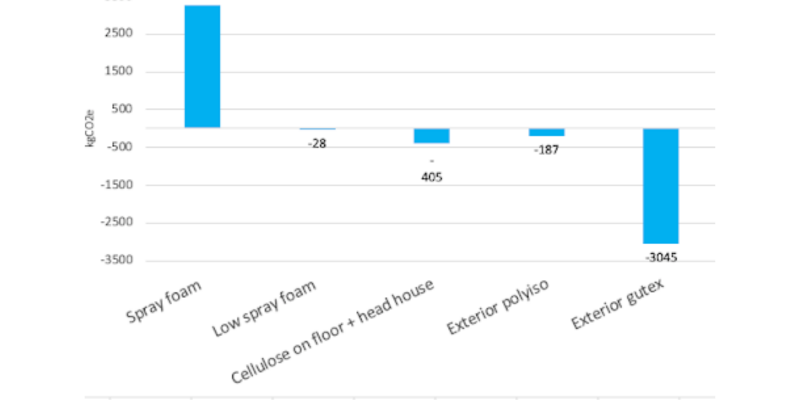

For homes, the biggest sources of embodied carbon are typically in materials. Many common materials used in construction, such as concrete, stone, steel, and lumber, tend to be high in embodied carbon either due to energy-intensive extraction or manufacturing processes. Even products made from rapidly renewable materials, or by a manufacturer that uses renewable energy, may waste a lot of water, or raw or finished materials. Or the product must travel overseas, or lasts only a short time before it heads for the landfill and must be replaced.

An exception to looking for the lowest carbon equation would be if the building materials are used for carbon sequestration. For instance, natural renewable materials such as wood from sustainable forests, or wool, or bamboo will hold carbon safely within the walls and furnishings of your home, while the natural source is replenished and continues to grow and pull more carbon from the atmosphere.

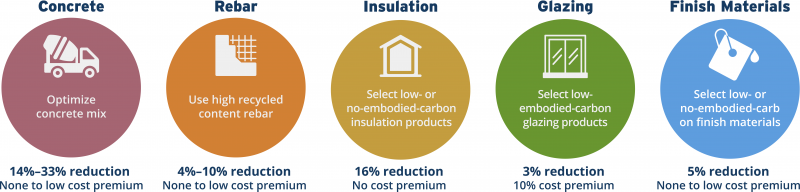

To reduce the embodied carbon in your home, as the saying goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure. The most accurate analysis of the embodied carbon in extraction, transportation, and manufacturing is going to come from the product manufacturer. Eco-conscious companies often use environmental product declarations (EPDs) and post the data on their websites. These look beyond carbon and account for multiple environmental impacts. Further, they provide a lifecycle assessment (LCA), and include both embodied carbon through end-of-life and operational carbon.

Experts can help

Many software tools exist to help conduct LCAs. One of the best free tools out there is the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (EC3). This tool can technically be used by anyone, but it is most efficient if used between your architectural, engineering, and construction professionals along with a trained sustainability professional or firm. Increasingly, the emphasis shifts to embodied carbon as building codes call for increased energy efficiency, and more homes and utility grids are powered by renewable energy—thus significantly lowering the carbon footprint of operational carbon emissions.

By looking at these issues, weighing pros and cons, we can help reduce the embodied carbon and thereby the total lifecycle carbon in our homes. Particularly in new construction and all-electric homes, just a few adjustments in key areas—insulation, cladding, and concrete—can make strides toward meeting our collective climate change commitments and averting the worst of the climate change catastrophes to come.

The Author: Sustainability Consultant Arnaldo Perez-Negron is an environmentalist and social entrepreneur based in the Tampa Bay area.