Stop the Presses: Can Adapting an Abandoned Newspaper Facility Revitalize the Suburbs?

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

When you think of the American suburbs, what words come to mind?

No matter how much affection you have for your hometown, one of those words is probably “bleak.” While many millennials, including this author, are still moving out to the suburbs to raise children — a pattern first established by their grandparents in the post-war era — few see these car-centric communities as ideal. The charmless strip malls, the big box stores, the neglected highway medians filled with litter from passing cars — how can one contemplate all this without crying out in despair?

The question isn’t really if the suburbs are bad but why they are this way. Are the people who live in the suburbs really more boring than the people in cities? Or does the archetypal suburban ambiance of loneliness and fatigue stem instead from poor urban planning?

Tract housing in a suburb of Cincinatti, Ohio, 2005. Photo by Derek Jensen via Wikimedia Commons.

My feeling is that it is the latter. Culture happens in places where people have the opportunity to move around, observe each other, and interact. The flâneur, that prototype of the modern artist or bohemian, emerged in mid 19th century Paris at the same time that the arcades were constructed, and this was no coincidence. As Baudelaire understood, the arcades provided the first modern artists with a stage on which to observe la comédie humaine firsthand. He argued that this new way of relating to society produced modern subjectivity as we know it.

It stands to reason that the suburbs, by removing would-be flâneurs from their stage, sapped their creativity as well. A life that moves from home, to car, to cubicle, to drive-through and back provides few chances for people to observe and interact with one another. Over time, the suburbs have led to an epidemic of loneliness in America — a fact that has been recognized since at least 2000, when political scientist Robert D. Putnam published his best-selling book Bowling Alone.

This trend has only been exacerbated during and after the pandemic, as more Americans have begun not only to work from home, but to have their groceries, entertainment and other consumer goods delivered straight to their doorstep, obviating the need to go outside altogether. This has led to a shuttering of retail spaces in the suburbs, among other changes. Suddenly, people are nostalgic even for those commercialized, “fake” public spaces like the mall that were widely derided in the 90s.

The Press won the 2023 A+ Jury Award for Commerical Renovations and Additions.

So how to fix it? What the suburbs need, most of all, are places where people can work, shop, wander and simply be. One project that tries to restore some of this urban energy to the suburbs is The Press, a former Los Angeles Times printing facility in Costa Mesa, California that was “reincarnated as a multidisciplinary workspace with a dining Canteen and a public Rail Trail on its 23.4-acre site” by Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects. Located in Orange County, California, Costa Mesa is a small city with a decidedly suburban feel, a place where people sit in traffic for twenty minutes to reach the In-N-Out Burger drive through.

This project, which won the 2023 A+ Jury Award in the Commercial Renovations and Additions category, stands out for seeming like a truly inviting, interesting place to spend time. Not just an office building, and not just a place to shop or eat, The Press avoids the sense of falseness or contrivance that plagues most suburban workspaces and shopping centers. While this is of course a privately owned campus, it feels more public than, for instance, a mall.

Industrial details elevate The Press above most commercial spaces one finds in the American suburbs.

Part of this is due to the sense of history that is preserved in the space. As the architects explain in their project notes, “precise cuts through precast concrete walls and roofing bring in fresh air, daylight and views. This subtraction exposes the beauty of the existing, reviving what has since been neglected and inviting the landscape to enter in through and around the campus.” Like a repurposed Bushwick warehouse, or even a Parisian arcade, The Press preserves a sense of place that pushes against the anonymity of “cookie cutter” suburbs.

Some of the details in this project are just extraordinary. As the architects explain, “The design celebrates both material and organic markers of time. Paint chips, rail spurs and conveyor belts are left as is and an existing tree is placed to grow through the structure itself — hinting at history, site and context.” My favorite detail is probably the rail trail, a partly shaded walking path that follows the course of a former rail line. Like the now iconic New York High Line, the Rail Trail repurposes outdated infrastructure in a way that both feels perfectly natural and encourages health and interaction.

The Rail Trail gives Costa Mesa, California its own version of the High Line. A stunning feature of the project is that its campus extends over 23 acres.

Time will tell how The Press evolves with its environment. Currently, the complex has fifty-five tenants, including a number of incredible artisans and local restaurants. My hope is that, with this project, Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects have created a template for a new kind of suburban redevelopment, one that works with existing architecture to imprint the faceless suburbs with a vibrant sense of place.

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

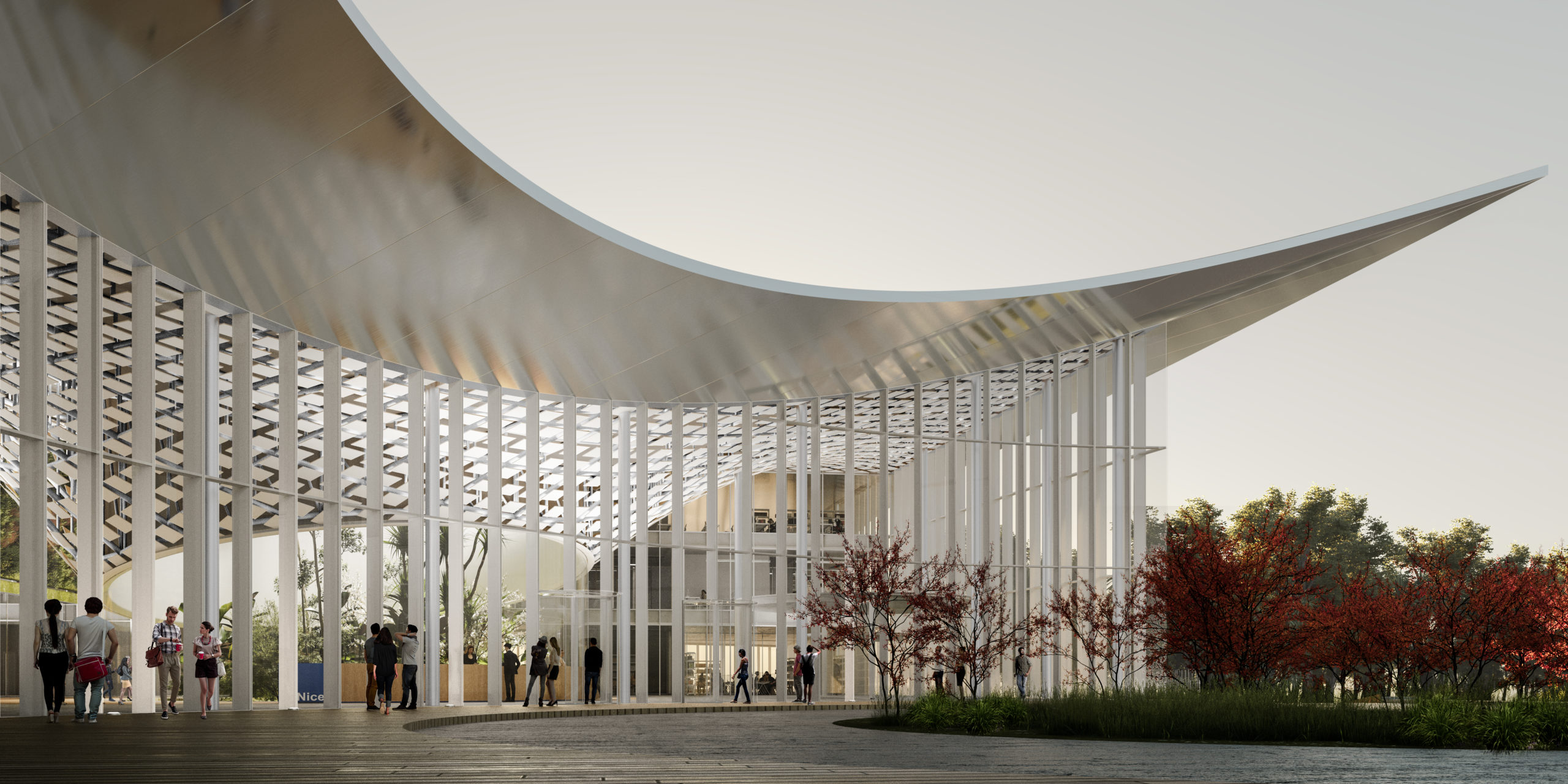

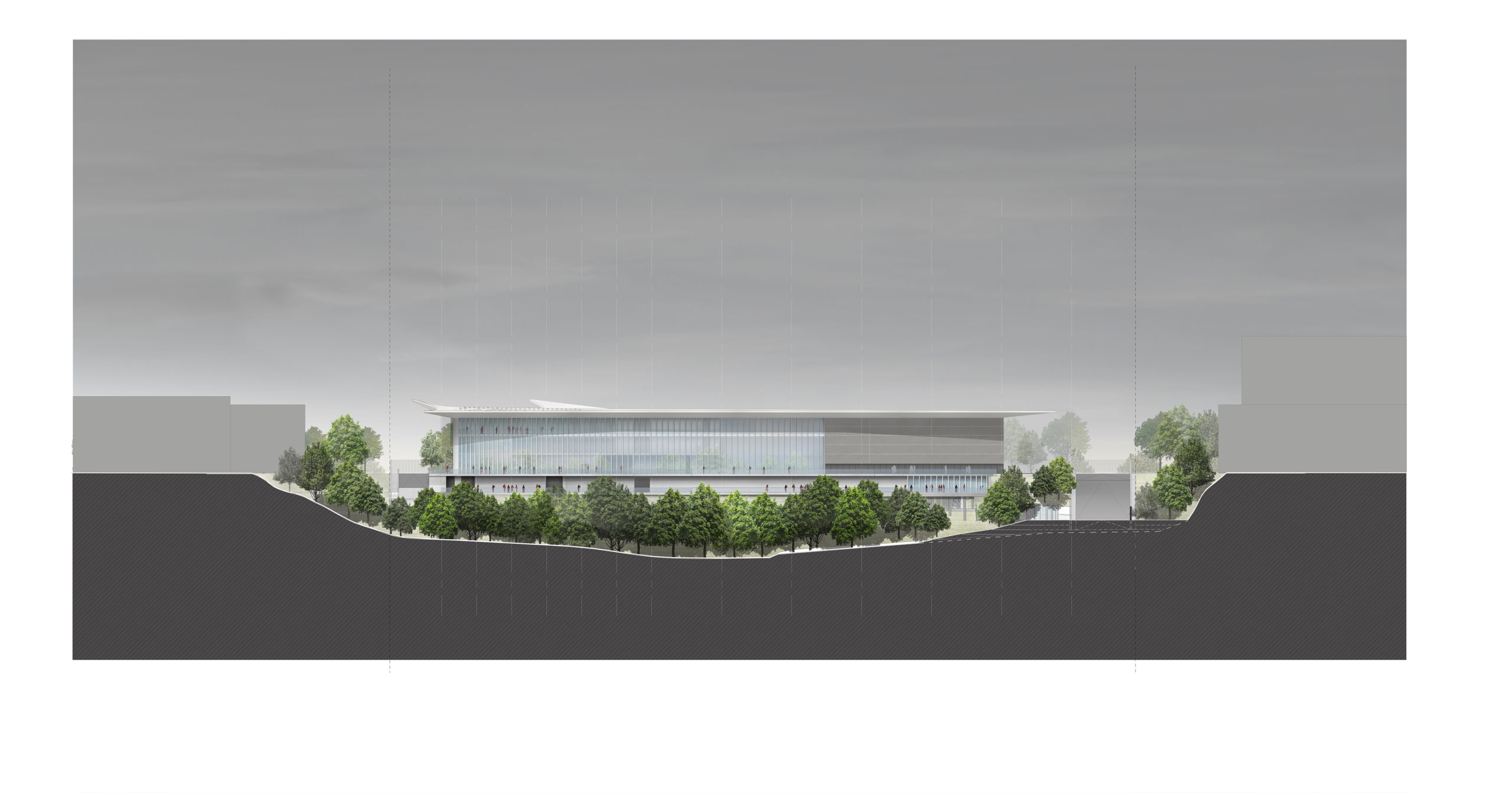

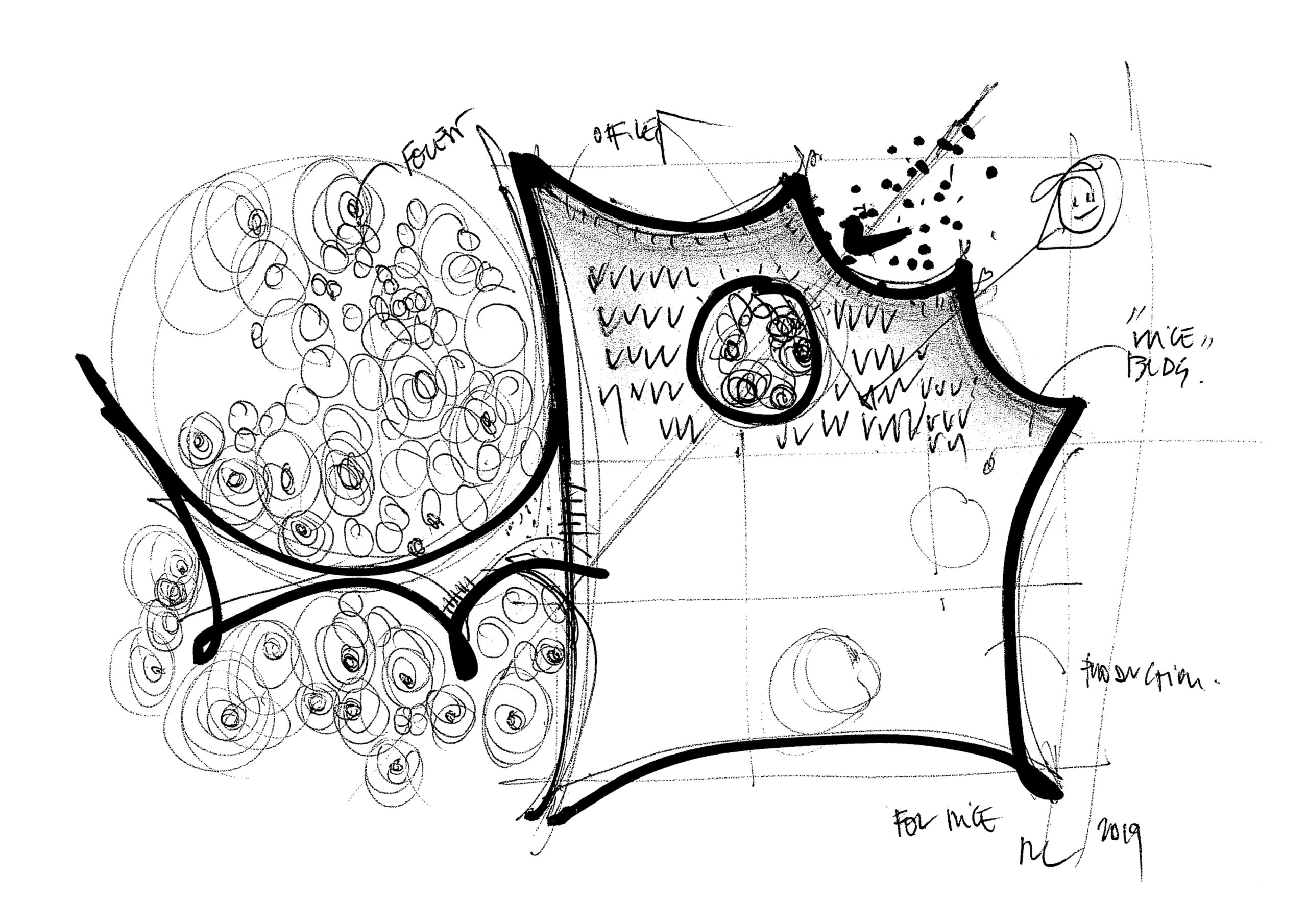

The intervention is, on the one hand, a manifesto of cutting-edge technology aimed at increasing productivity according to a sustainable business model. Meanwhile, on the other, this is an architecture of social commitment to promote the professional growth of the local community by leveraging constant training and innovative work experiences.

The intervention is, on the one hand, a manifesto of cutting-edge technology aimed at increasing productivity according to a sustainable business model. Meanwhile, on the other, this is an architecture of social commitment to promote the professional growth of the local community by leveraging constant training and innovative work experiences. Also at the back, a system of suspended paths, immersed in nature, connects to the building that houses services for employees, such as the gym and the inevitable “churrasqueira.” The working environment is a bit like a home, where it is also pleasant to spend moments of relaxation and socializing.

Also at the back, a system of suspended paths, immersed in nature, connects to the building that houses services for employees, such as the gym and the inevitable “churrasqueira.” The working environment is a bit like a home, where it is also pleasant to spend moments of relaxation and socializing. In general, the use of natural ventilation is possible for two thirds of the year, thanks to openable facade elements and the integration of mobile openings in the atrium patio that transform it into a giant “ventilation chimney”. The production area, thanks to the combination of thermal mass and natural ventilation, is operational all year round without the need for cooling or heating; showrooms and offices benefit from a mixed system that encourages natural ventilation while reducing overall cooling loads.

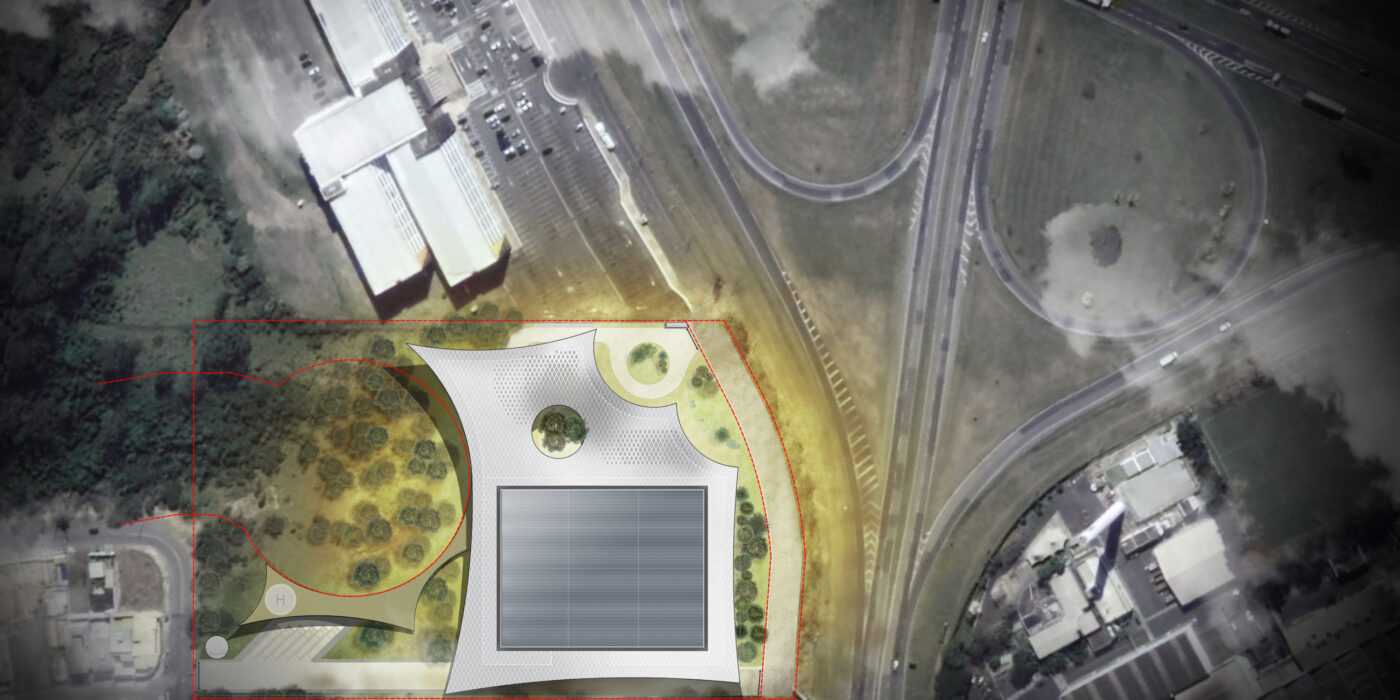

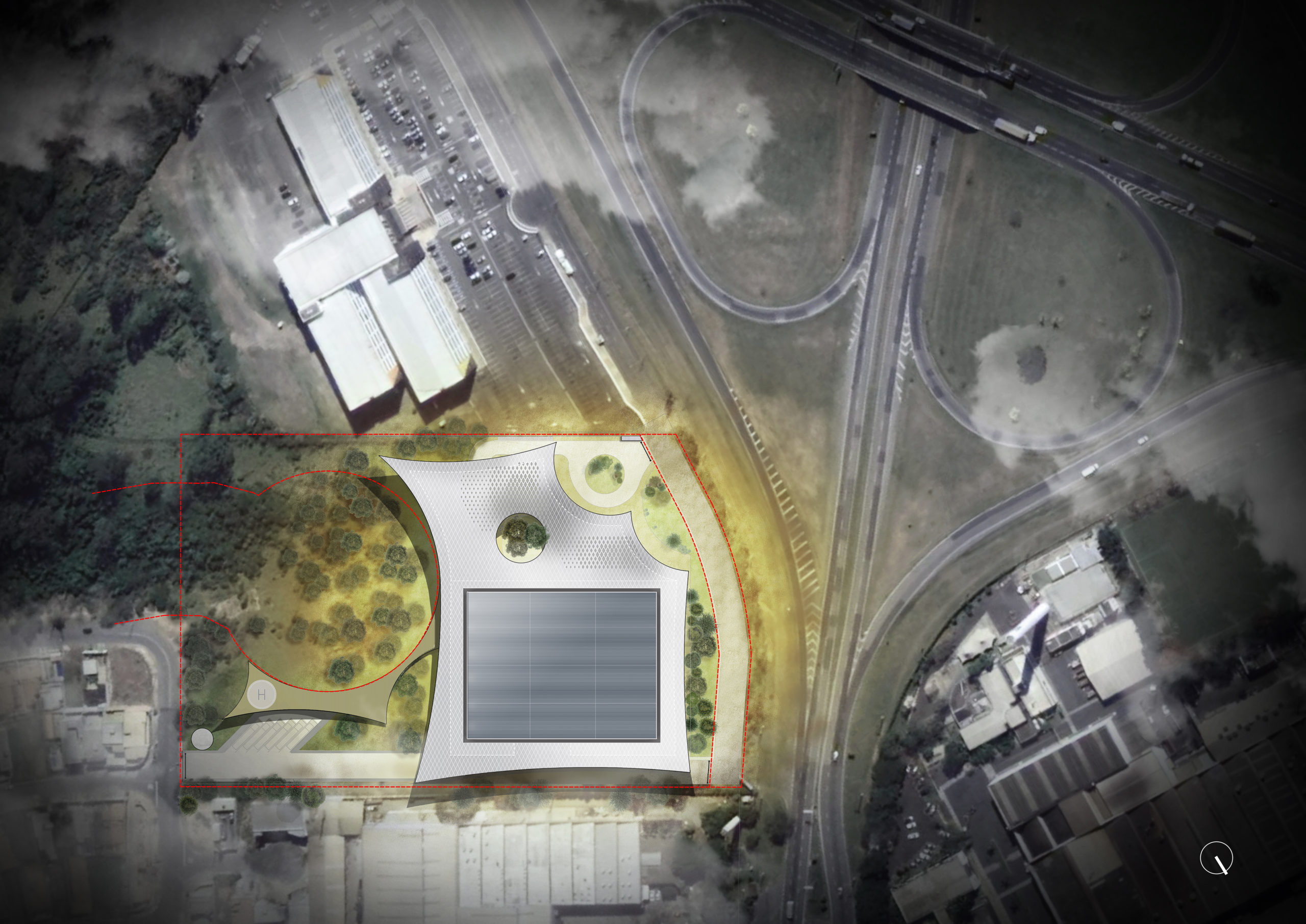

In general, the use of natural ventilation is possible for two thirds of the year, thanks to openable facade elements and the integration of mobile openings in the atrium patio that transform it into a giant “ventilation chimney”. The production area, thanks to the combination of thermal mass and natural ventilation, is operational all year round without the need for cooling or heating; showrooms and offices benefit from a mixed system that encourages natural ventilation while reducing overall cooling loads. The landscape design is an equally important part of the intervention and is functional to increase the rich local biodiversity. The project proposes a playful interpretation of the variety of the Cerrado biome, the second largest in Brazil, ranging from grassy glades, to savanna, to forest formations, represented here in different expressive languages along the outdoor paths, inspired by local wild species and native vegetation. Small ponds and water basins mitigate runoff and direct rainwater to a large basin at the bottom of the area; a 2, 120 cubic foot (60 cubic meter) tank stores water to reuse for irrigation.

The landscape design is an equally important part of the intervention and is functional to increase the rich local biodiversity. The project proposes a playful interpretation of the variety of the Cerrado biome, the second largest in Brazil, ranging from grassy glades, to savanna, to forest formations, represented here in different expressive languages along the outdoor paths, inspired by local wild species and native vegetation. Small ponds and water basins mitigate runoff and direct rainwater to a large basin at the bottom of the area; a 2, 120 cubic foot (60 cubic meter) tank stores water to reuse for irrigation.