4 Novels About Architecture That Are Better Than “The Fountainhead”

Sooner or later, every architect is gifted The Fountainhead. Usually, this is done with good intentions: someone reads Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel about an idealistic architect at war with a cynical society and is reminded of the architect in their own lives, their friend or nephew or whomever. They buy the architect a copy, thinking they will appreciate seeing their profession represented in literature.

Sometimes though, Fountainhead pushers have another agenda. Rand’s 753 page doorstop was not just a work of imaginative literature; it was a vehicle for Ayn Rand to push her political ideology, an extreme form of capitalist individualism called Objectivism. Rand hoped readers of The Fountainhead would be convinced of the evils of collectivism, especially any kind of socialism, which in her view suppresses the entrepreneurial spirit of geniuses like her architect hero Howard Roark. She wanted to change the way people voted, not just how they thought about architecture.

As it is a work of political propaganda, The Fountainhead falls short of John Keats’s standard for authentic literature. In an 1817 letter to his brothers George and Thomas, the poet coined the term “negative capability” to describe the ability of great authors to put their own opinions to the side when they set out to write. The role of the author, in Keats’s view, is not to push an agenda but to give life to whatever ideas emerge organically within the imaginative space of the poem or novel.

A lofty standard? Maybe. But the novels listed here come closer to the mark than The Fountainhead. They run where Rand’s book only walks — that is, they give authentic literary expression to architectural ideas.

Daniel Burnham’s “White City,” constructed in 1893 for the Chicago World’s Fair. Unidentified Photographer, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The reader might here exclaim that I am cheating. “The Devil in the White City is not a novel at all,” they’ll say, “it is a work of non-fiction!”

True as that may be, The Devil in the White City is by Keats’s standard a clear example of imaginative literature. In re-telling the events surrounding the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and its architect, Daniel Burnham, author Erik Larson set out, above all else, to tell a story and to do so as powerfully as he could. As New York Times critic Janet Maslin gushed, Larson “relentlessly fuses history and entertainment to give this nonfiction book the dramatic effect of a novel, complete with abundant cross-cutting and foreshadowing.”

Larson’s approach is well suited to his dramatic subject matter. The story alternates between two narratives: the planning and development of the World’s Fair under architect Daniel Burnham, who used the fair as an opportunity to showcase the grandeur of the Beaux Arts Style, and the exploits of serial killer H.H. Holmes, who used the fair as an opportunity to prey on naive out-of-towners.

In a grim ironic twist, Holmes was something of an architect himself, transforming a Chicago rooming house into a “Murder Castle” complete with trapdoors, greased chutes and soundproof rooms. Indeed, the parallels between Burnham and Holmes are the thematic heart of the book, lending this true story literary gravitas.

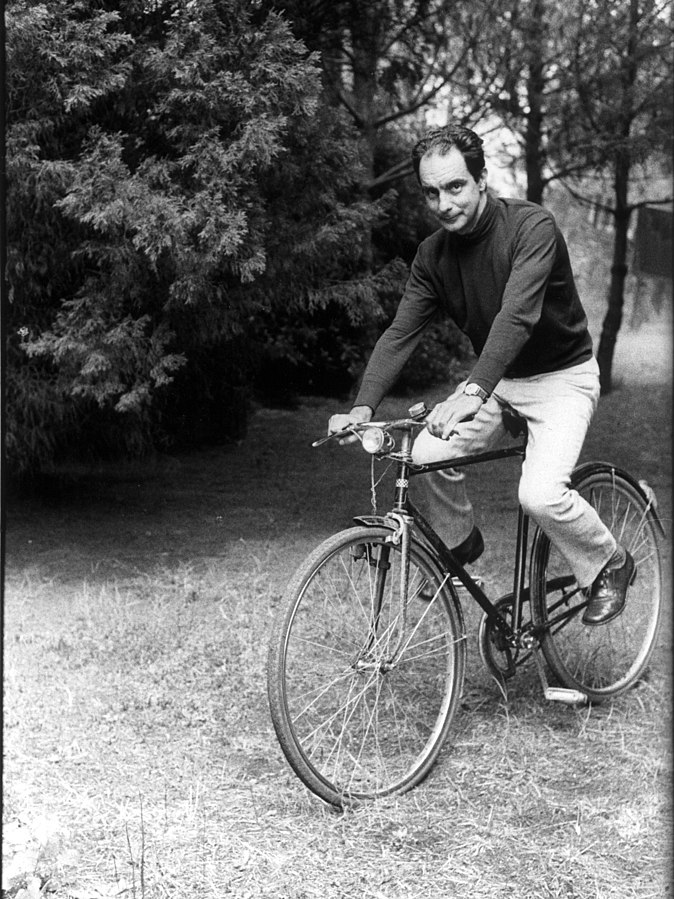

Italo Calvino riding a bike in 1970. Unknown Photographer, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Like a great building, Invisible Cities is a book that was designed to be inhabited rather than simply experienced once. The allegorical novel is structured as a series of conversations between Marco Polo, the 13th century Italian explorer, and Kublai Khan, the Mongol emperor of China.

Polo and Khan did meet in history, but this book is not drawn from any historical sources. The conversations are merely a framing device, allowing Polo to describe 55 fictitious cities to the emperor, places he claims to have visited. Each city is a parable for a different aspect of human nature, and as the novel progresses, it becomes clear that the subject Polo has learned the most about in his travels is himself. Places, it seems, are illuminated by the preconceptions we bring to them.

While the story has a free-floating and dreamlike structure, there is a plot twist that occurs halfway through the novel. Pressed by Kubla Khan to describe his home city of Venice, Polo explains that he has been doing that all along. Fedora, Zoe, Zenobia, and all the other fictional cities he recounts are all just Venice seen from different vantage points.

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski (2000)

Leaves are much more intricate than they appear to be at first. Photo by Jon Sullivan, 2003, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

House of Leaves is sort of like the reading equivalent of being trapped within H.H. Holmes labyrinthine Murder Castle. The text is laid out in a fashion that is anything but linear, with copious footnotes leading to their own footnotes which themselves have footnotes, all making copious references to books and films that are sometimes real, sometimes not. At times, the text is arranged unusually on the page and the book must be rotated to be read. At other times, multiple narrators interrupt one another in a disorienting fashion. Even the genre is hard to determine. While most readers consider House of Leaves a horror story, the author himself has described it — bafflingly perhaps — as a love story.

But House of Leaves offers the reader much more than mere confusion. By traversing this experimental book, the reader is able to share in the protagonists’ disorientation, offering a unique, sometimes claustrophobic experience of imaginative identification. The book follows a family whose house contains an endless series of hidden rooms — an allegory, perhaps, for the psyche, family dynamics, academic criticism, history and more. (Perhaps the list is also endless). For architects, the mysteries of this novel are a potent reminder that clarity, rationality, and openness are not always preferable. Sometimes people are drawn to the darkness.

Am Gestade, one of many Viennese streets Austerlitz traverses as he searches for his hidden past. Photo by Jorge Franganillo, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Can a work of art speak to both the heart and head at the same time? Or do the intellect and the emotions respond to different kinds of artistic experience, one craving critical distance and the other empathic closeness? These are not just questions that Austerlitz poses to the reader, they are the questions faced by the novel’s eponymous protagonist.

Jacques Austerlitz is an architectural historian who lives a solitary, itinerant life. He is fascinated with the way buildings and street layouts can reveal the buried histories of places, leaving behind an objective record of how people lived — ordinary people, that is, not just the type of people whose names end up in history books. One day, Austerlitz stumbles across a startling fact about himself. He learns that the couple who raised him in England were not his biological parents. His actual parents were a Jewish couple from Vienna who perished in the Holocaust. They had sent their young son, then aged three, to safety in England using an underground program known as the kindertransport.

Austerlitz applies his skills as an architectural historian to research the buried history of his own parents, who seem to have left few traces behind. He is then faced with the possibility that he had unknowingly been looking for them all along. Could his interest in architectural history have been, unconsciously, a way of trying to uncover his own roots? This question, which would intrigue Calvino’s Marco Polo, is just one of the many tantalizing mysteries of this masterful novel about memory and loss.

Cover Image: Freepik, Attribution via Wikimedia Commons