Brasserie des Pres draws on the vibrant history of Paris’s Latin Quarter

The storied location of this brasserie in Paris inspired interior studio B3 Designers to fill the restaurant with tasselled chairs, disco balls and other flamboyant decor.

Brasserie des Pres is set in Paris’s Latin Quarter, which was a hub of creativity throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, its cafes filled with artists, publishers and prominent writers including Ernest Hemingway and Jean-Paul Sartre.

London-based studio B3 Designers aimed to infuse this same buzzy ambience into the quarter’s latest eatery, undeterred by its awkwardly narrow interiors.

“Brasserie des Pres has a very unique floor print and we’ve used the existing architecture to create layers of dining experiences,” the studio said. “We’ve created a feeling of community and delight, a welcoming backdrop to the great food served here.”

Lush with greenery, the exterior of the restaurant features a striped orange awning and classic Parisian terrace seating.

Once guests step inside, they find themselves in a large dining room with red-panelled walls, inset with mirrored shelves that display an assortment of shapely glass vessels.

Decorative tiles depicting limes, lemons and oranges are incorporated at the top of each panel.

Tables throughout the room are dressed with white linen cloths and bijou brass lamps, nodding to the table set-up of the Latin Quarter’s traditional eateries.

Guests also have the option to sit at a high marble counter that directly overlooks Brasserie des Pres’s bustling kitchen or enjoy a drink at the bar, which is fronted by velvet-lined orange stools.

More dining space is provided on the first floor, where the shelves along the walls are filled with antique books and candelabras to mimic the worldly look of a cabinet of curiosities.

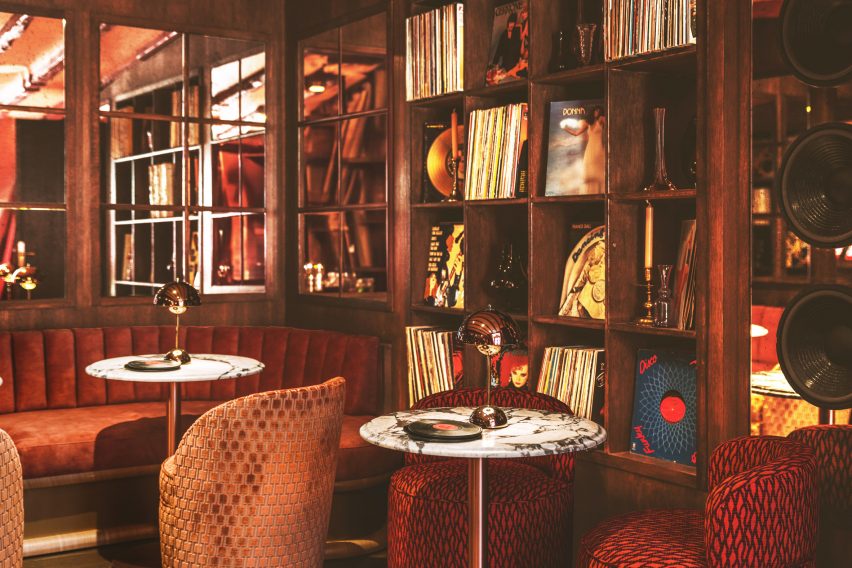

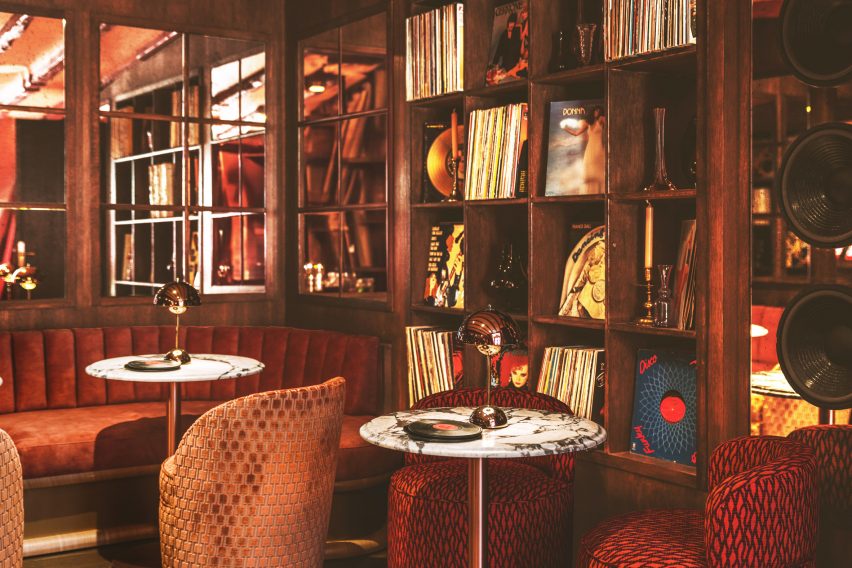

Finally, on the top floor of the restaurant is a lounge-style space where guests can relax while selecting tracks from the brasserie’s vinyl record library.

A curtained partition can be drawn back to reveal a secret bar, complete with a mirrored ceiling. From its centre hangs a cluster of disco balls, enclosed by a circular neon sign that spells the word groovy.

A plush, crimson banquet winds around the periphery of the space, accompanied by matching tassel-backed chairs and marble tables.

Even the toilets at this level are finished with eccentric details including a pearl-laden chandelier that droops above the washbasin and surreal gold-framed paintings that depict the eyes of “unsung Parisian anti-heroes”, according to B3 Designers.

Paris’s rich culinary scene is constantly expanding.

Other spots that have recently opened up around the city include Citrons et Huîtres, an oyster bar that’s designed to resemble a fishmonger, and Chinese restaurant Bao Express, which has a retro interior informed by Hong Kong diners of the 1970s.

The photography is by Vincent Remy and Joann Pai.

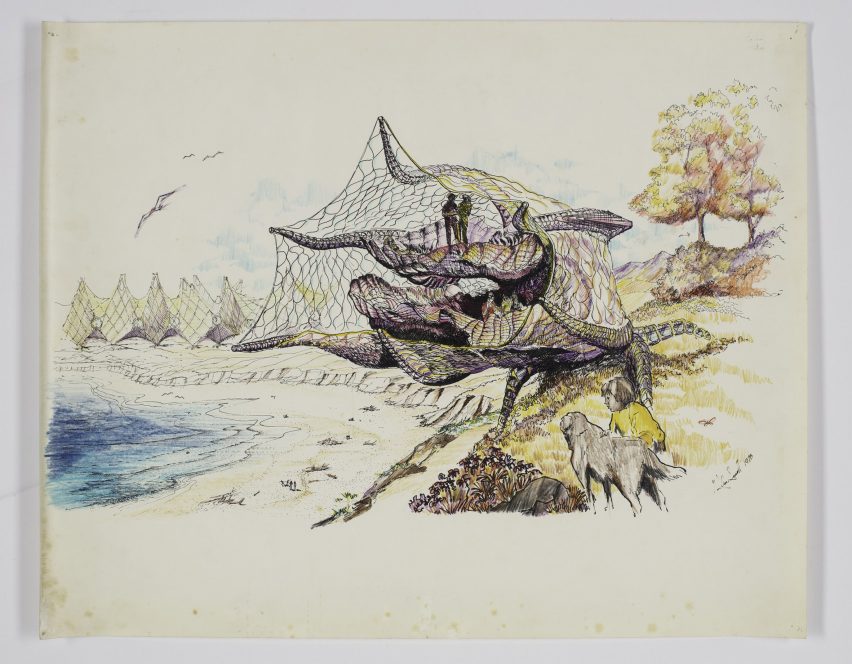

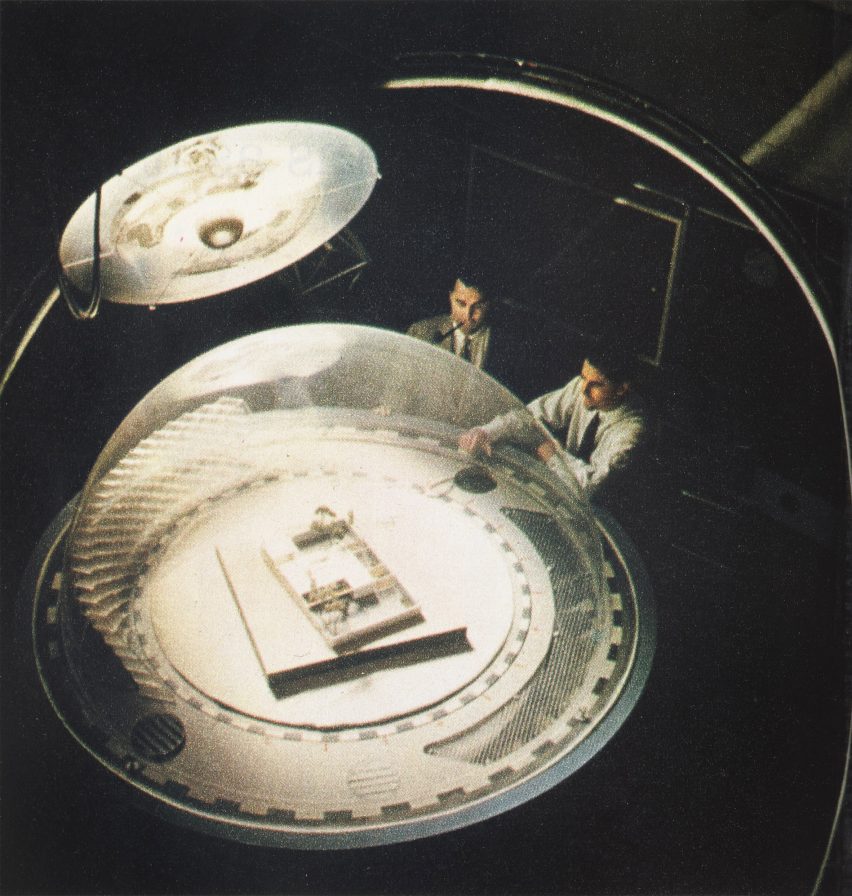

Though many architectural enthusiasts around the world may only now be acquainting themselves with his larger body of work, they are likely already familiar with his design for the 2017 Serpentine Pavilion — a timber structure accented with indigo blue that ingeniously connected different times and spaces and reinterpreted form of the massive tree at the heart of his home town.

Though many architectural enthusiasts around the world may only now be acquainting themselves with his larger body of work, they are likely already familiar with his design for the 2017 Serpentine Pavilion — a timber structure accented with indigo blue that ingeniously connected different times and spaces and reinterpreted form of the massive tree at the heart of his home town.