Ten homes with staircases that have statement balustrades

In our latest lookbook, Dezeen has rounded up 10 home staircases that incorporate contemporary and non-traditional balustrades from circular perforations to bold colour blocking.

A balustrade is a railing that runs alongside a staircase and prevents a person from falling over its edge. Balusters are vertical posts that typically support a bannister or handrail above, balusters traditionally have a lathe-turned form that results in a bulbous and curving profile.

Although often focal points of interior settings, balustrades can be relatively similar from home to home. In this lookbook, we have highlighted 10 alternative balustrades that bring a non-traditional and statement look to homes.

This is the latest in our lookbooks series, which provides visual inspiration from Dezeen’s archive. For more inspiration see previous lookbooks featuring maximalist interiors, homes that use tiles as a decorative feature and interiors with ornate ceilings.

Private House in Cologne, Germany, by SMO Architektur

This perforated balustrade complements the rigid and cubic form of this house in Cologne, which was designed by architecture practice SMO Architektur and informed by Le Corbusier’s Plan Libre.

A staircase that runs through the home was bounded by a seamless, perforated balustrade that is constructed from a singular sheet of material. The perforations within the balustrade contrast against the square and angular shape profile of the staircase.

Find out more about Private House in Cologne ›

Mo-tel House, UK, by Office S&M

This brightly coloured staircase sits within a Georgian townhouse in the London borough of Islington, which was renovated by London studio Office S&M.

Titled Mo-tel House, the home has a brightly coloured interior scheme with a geometric and boldly coloured staircase. Its vertically slatted balusters were painted pink while a bright yellow handrail folds over and into the staircase’s end post.

Find out more about Mo-tel House in London ›

Tel Aviv townhouse, Israel, by David Lebenthal

In Tel Aviv, architect David Lebenthal suspended a staircase behind a wall of vertically organised steel rods that function as the staircase’s balustrade.

The home was designed for Lebenthal and his family and was organised around an exposed concrete party wall that hosts the metal staircase that runs through the home. Steel rods stretch between each floor of the home and were fixed to and intersect with the outer edge of the metal-folded tread.

Find out more about Tel Aviv townhouse ›

White Rabbit House, UK, by Gundry & Ducker

Architecture studio Gundry & Ducker fitted a cantilevered staircase into this 1970s house in London.

Its balustrade is comprised of green-painted vertical rods that run the entire length of the staircase and a one-piece wooden bannister that was placed on top of the green balusters and pierces through an overhanging lip on the tread of the base step.

Find out more about White Rabbit House ›

Bonhôte House, UK, by AOC

Angular brass rods, arranged in a zigzagging formation, flank the sides of this staircase that ascends above an open-plan living and kitchen area in a north London townhouse.

The home was designed by architecture studio AOC within a contemporary family home. It has an open-plan design with its brass-wrapped staircase used to divide the ground floor living spaces

Find out more about Bonhôte House ›

Hearth House, UK, by AOC

Architecture studio AOC incorporated a negative relief-style balustrade into the staircase at Hearth House in Golders Green.

On the upper levels of the staircase, the profiles and silhouettes of traditional spindle balusters were laser cut into plywood sheets creating voids where ornamental spindles would sit. Elsewhere, a lamp extends from the handrail of the bannister.

Find out more about Hearth House ›

O12, Germany, by Philipp von Matt

German architect Philipp von Matt fitted a golden-hued, perforated-brass bannister to a solid concrete staircase at O12, an artist’s home in Berlin.

The mesh brass bannister zigzags along the side of the concrete stairwell from the front door of the home through to its first and second floors. As a result of its perforations, light can travel through the bannister and filter into the monolithic stairwell.

Find out more about O12 ›

Ash House, UK, by R2 Studio

A full-height ash bannister, which was pierced with circular cut-out openings lines a wooden stairwell that connects two storeys of an Edwardian house in Lewisham, London.

Architecture studio R2 Studio mimicked the stair profile when creating the hole pattern across the ash bannister, incorporating larger holes at eye level for both adults and children. A groove was cut into the opposite side to form an inset handrail.

Find out more about Ash House ›

Maryland House, UK, by Remi Connolly-Taylor

A red metal staircase at designer Remi Connolly-Taylor’s home in London has a weightless look. It has a red folded tread that sits on top of the home’s stone floors. Besides the tread, a tubular, pipe-like hand rail-cum-balustrade has a similarly weightless look and protrudes from the ground and follows the profile of the steps below.

The staircase is encased within a glass block-clad stairwell that Connolly-Taylor explained was used to bring light into the interior while also providing privacy from neighbours.

Find out more about Maryland House ›

Coastal House, UK, by 6a Architects

A wooden staircase sits at the heart of this home, which was renovated by London-based architecture studio 6a Architects. Thin tapering spindle-shaped balustrades were organised at alternating angles creating a wave-like rhythm across the entire staircase.

The bannister and balustrade were made from oak and have an unfinished, rustic quality that ties the staircase to the home’s original beams and textural stone walls.

Find out more about Coastal House ›

This is the latest in our lookbooks series, which provides visual inspiration from Dezeen’s archive. For more inspiration see previous lookbooks featuring deliberately unfinished interiors, maximalist interiors and walk-in wardrobes.

Full House by Leckie Studio Architecture + Design, Vancouver, Canada

Full House by Leckie Studio Architecture + Design, Vancouver, Canada

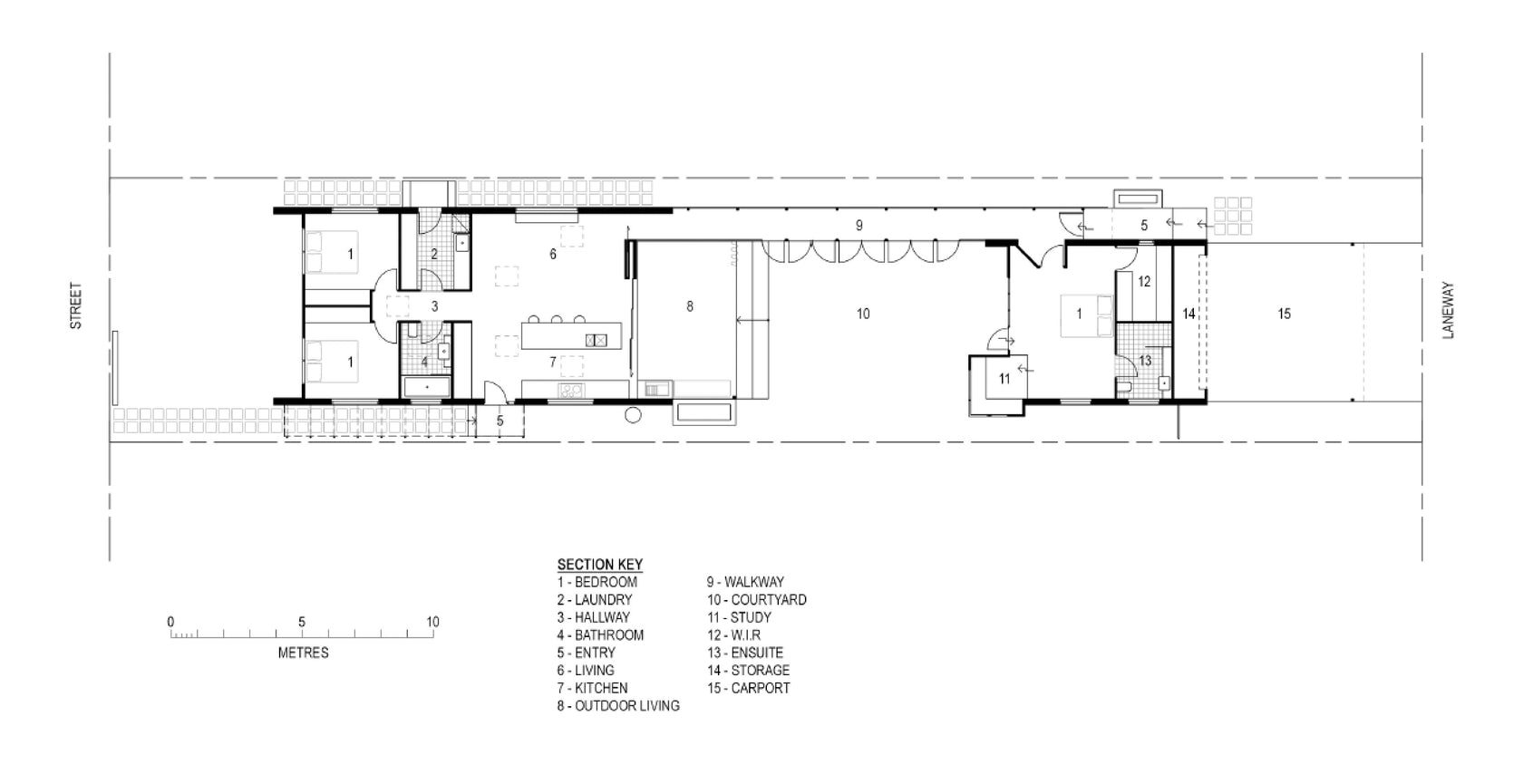

Laneway House by 9point9 Architects, Townsville, Australia

Laneway House by 9point9 Architects, Townsville, Australia

Rough House + Laneway, by Measured Architecture Inc., Vancouver, Canada

Rough House + Laneway, by Measured Architecture Inc., Vancouver, Canada

Laneway Wall Garden House by Donaghy & Dimond Architects, Dublin, Ireland

Laneway Wall Garden House by Donaghy & Dimond Architects, Dublin, Ireland

McIlwrick Residences by B.E. Architecture, Melbourne, Australia

McIlwrick Residences by B.E. Architecture, Melbourne, Australia

Riverdale Townhomes by Studio JCI, Toronto, Canada

Riverdale Townhomes by Studio JCI, Toronto, Canada