Children in social housing “sleeping on a blanket on a concrete floor”

Increasing numbers of people in social housing are living in inhospitable conditions because they are unable to afford even basic furniture and flooring, Dezeen reports as part of our Social Housing Revival series.

In the UK, social-rented homes are usually handed over to new residents in a sparse state – lacking basic elements of decoration and furnishings, as well as essential appliances.

As the cost of living continues to rise and the availability of crisis-support services diminishes, a growing number of people are unable to afford to furnish these homes, meaning they are sometimes forced to live in a harsh environment for months at a time.

“For the families who we work with, the point that is most distressing is the void condition – the homes are given and [social landlords] don’t bother painting the walls, and there’s absolutely no flooring down,” said Emily Wheeler, founder and CEO of Furnishing Futures.

“Most people over time can manage to get some furniture together that’s gifted to them from the local church or friends or family or whatever, but it costs thousands and thousands of pounds to put flooring down, even in a one-bedroom flat.”

London charity Furnishing Futures was recently established to address the issue among women fleeing domestic abuse, creating interiors to a high standard using furniture donated from brands.

Domestic-abuse survivors and people leaving care or who were previously homeless are particularly at risk of furniture poverty since they are less likely to have items to bring with them.

Wheeler said Furnishing Futures is seeing increasing demand for its services as more people come under financial pressure.

“Initially we were only working with women who were in receipt of benefits or experiencing severe poverty or destitution,” explained Wheeler.

“But now we’re working with families who are using the food bank but the woman is a midwife, or she’s a teaching assistant, or she is a teacher, and that is new.”

Sometimes the conditions the charity witnesses are shocking, Wheeler told Dezeen.

“People are experiencing real hardship,” she said. “We’ve frequently come across people who have no food, no clothes, no shoes for their children.”

“The kids are sleeping on a blanket on a concrete floor – there’s nothing in the flat whatsoever,” she continued. “And those people might even be working as care assistants, or teaching assistants. So it’s really, really difficult at the moment for people.”

According to the campaigning charity End Furniture Poverty, more than six million people in the UK lack access to essential furniture, furnishings and appliances – including 26 per cent of those living in social housing.

Only two per cent of social-rented homes in the UK are let as furnished or partly furnished, the charity’s research has found.

Wheeler is a trained interior designer who formerly worked in child safeguarding.

She was prompted to set up Furnishing Futures after discovering that many women in social housing who had left dangerous homes were driven back to their abuser by poor living conditions.

“When women were placed in new housing after having escaped really high-risk situations, they sometimes felt that they had no choice but to return because they couldn’t look after their children in those conditions – there’d be no fridge, no cooker, no washing machine, no bed, no curtains on the windows,” she explained.

“People are expected to go to those places at a time of great trauma and distress, and recover, but those places are often not conducive to that because of the design and the environment.”

The charity overhauled 36 homes in 2023, helping 99 women and children. It takes a design-led approach with an emphasis on finishing interiors to a high standard.

“We professionally design them and they look like beautiful homes – they look like show homes when they’re finished,” Wheeler said.

“And the reason we do that is because it’s really important that the women feel that they have a beautiful home and they feel safe there, that they feel for the first time that someone really cares about them,” she added.

“It also supports the healing and the recovery journey for those women.”

To help ensure quality, the charity only works with new or as-new furniture. It works with brands to source items that would otherwise be sent to landfill – usually press samples or items used at trade shows, in showrooms or on shoots.

Donating partners include Soho Home, BoConcept, Romo Fabrics and House of Hackney.

Wheeler is keen for Furnishing Futures to expand beyond London but the charity is currently held back by limited warehouse capacity and funding.

“If we had more money and more space we could help more people, it’s as simple as that, really,” she said.

The charity continues to seek donations from brands, particularly for bedroom furniture and pieces for children.

As well as calling for social-housing providers to let their properties in a better state, Wheeler believes the design industry could be doing more to help people facing furniture poverty.

“I do think that where the industry could catch up a little bit is working with organisations like ours,” she said.

For example, charities are unable to take furniture lacking a fire tag – which tend to be removed – so imprinting this information onto the items themselves would make more usable.

In addition, donating excess items as an alternative to sample sales could be a way to reduce waste with much greater social impact, she suggests.

“There’s probably millions of people across the country living without basic items and yet there’s massive overproduction, but the waste isn’t necessarily coming to people who actually need it,” Wheeler said.

“There are things that the industry could be doing that will create a huge social impact very easily.”

The photography is courtesy of Furnishing Futures unless otherwise stated.

Social Housing Revival

This article is part of Dezeen’s Social Housing Revival series exploring the new wave of quality social housing being built around the world, and asking whether a return to social house-building at scale can help solve affordability issues and homelessness in our major cities.

New York is a city known for housing scarcity, and a place that’s defined by reinvention. For Timber House, MESH Architectures was inspired by natural finishes and “botanical architecture.” The idea was not only to foster well-being, but create a new model for timber construction in the city. The project is the first mass-timber condominium in New York, and the structure was built with glue-laminated timber columns, beams, and floor plates. The six-story, multifamily project is comprised of fourteen homes.

New York is a city known for housing scarcity, and a place that’s defined by reinvention. For Timber House, MESH Architectures was inspired by natural finishes and “botanical architecture.” The idea was not only to foster well-being, but create a new model for timber construction in the city. The project is the first mass-timber condominium in New York, and the structure was built with glue-laminated timber columns, beams, and floor plates. The six-story, multifamily project is comprised of fourteen homes.

MVRDV has earned a reputation for reinvention and creating new building forms. That same approach extends to housing, where the team designed Valley with a more “green and human” touch. Built for developer Edge, the project is located in Amsterdam Zuidas. Rising to three distinct towers, the façades shift across the complex. The outer edges are mirrored glass, while the inner façades are clad with stone and swaths of greenery.

MVRDV has earned a reputation for reinvention and creating new building forms. That same approach extends to housing, where the team designed Valley with a more “green and human” touch. Built for developer Edge, the project is located in Amsterdam Zuidas. Rising to three distinct towers, the façades shift across the complex. The outer edges are mirrored glass, while the inner façades are clad with stone and swaths of greenery.

Few locations are more prominent for multifamily housing in St. Louis than Forest Park. Designed by Studio Gang, One Hundred is a residential tower overlooking the park and the studio’s first project in the city. The tower includes a mix of housing, retail and amenities on four-story stacked tiers. The apartments were designed for views of Forest Park and east to the Gateway Arch.

Few locations are more prominent for multifamily housing in St. Louis than Forest Park. Designed by Studio Gang, One Hundred is a residential tower overlooking the park and the studio’s first project in the city. The tower includes a mix of housing, retail and amenities on four-story stacked tiers. The apartments were designed for views of Forest Park and east to the Gateway Arch.

The Cirqua project by BKK gained widespread recognition for creating beautiful, inventive multifamily architecture. The project includes 38 unique unit types out of the 42 total apartments made with spacious balconies and an integrated approach to landscaping. Combining two properties into a single block, the project was formed with careful attention paid to scale and the surrounding context. Cirqua not only showcases a smart, nuanced approach to multifamily housing, but also how to design for accessibility and passive performance.

The Cirqua project by BKK gained widespread recognition for creating beautiful, inventive multifamily architecture. The project includes 38 unique unit types out of the 42 total apartments made with spacious balconies and an integrated approach to landscaping. Combining two properties into a single block, the project was formed with careful attention paid to scale and the surrounding context. Cirqua not only showcases a smart, nuanced approach to multifamily housing, but also how to design for accessibility and passive performance.

Caterpillar approaches density through a novel construction and design in Core City, Detroit. It utilizes a Quonset Hut structure that holds eight units, all entirely prefabricated. The result is an 8,000 square foot (745 square meter) residential project that prioritizes indoor and outdoor space. Prince Concepts created the project with tall ceilings that rise to 23 feet (7 meters); the units were designed to capture morning light in the bedrooms and evening sunsets in the living room.

Caterpillar approaches density through a novel construction and design in Core City, Detroit. It utilizes a Quonset Hut structure that holds eight units, all entirely prefabricated. The result is an 8,000 square foot (745 square meter) residential project that prioritizes indoor and outdoor space. Prince Concepts created the project with tall ceilings that rise to 23 feet (7 meters); the units were designed to capture morning light in the bedrooms and evening sunsets in the living room.

CPDA Architects designed this garden house project as a multifamily development in Mexico City. Located in the Escandón neighborhood, the project includes fourteen residential units. At its heart, a central courtyard is the connective element that defines the housing project, opening up access to natural light and cross ventilation. Ten townhouse units are set up the four ground-floor units below, all of which share a similar material relationship.

CPDA Architects designed this garden house project as a multifamily development in Mexico City. Located in the Escandón neighborhood, the project includes fourteen residential units. At its heart, a central courtyard is the connective element that defines the housing project, opening up access to natural light and cross ventilation. Ten townhouse units are set up the four ground-floor units below, all of which share a similar material relationship.

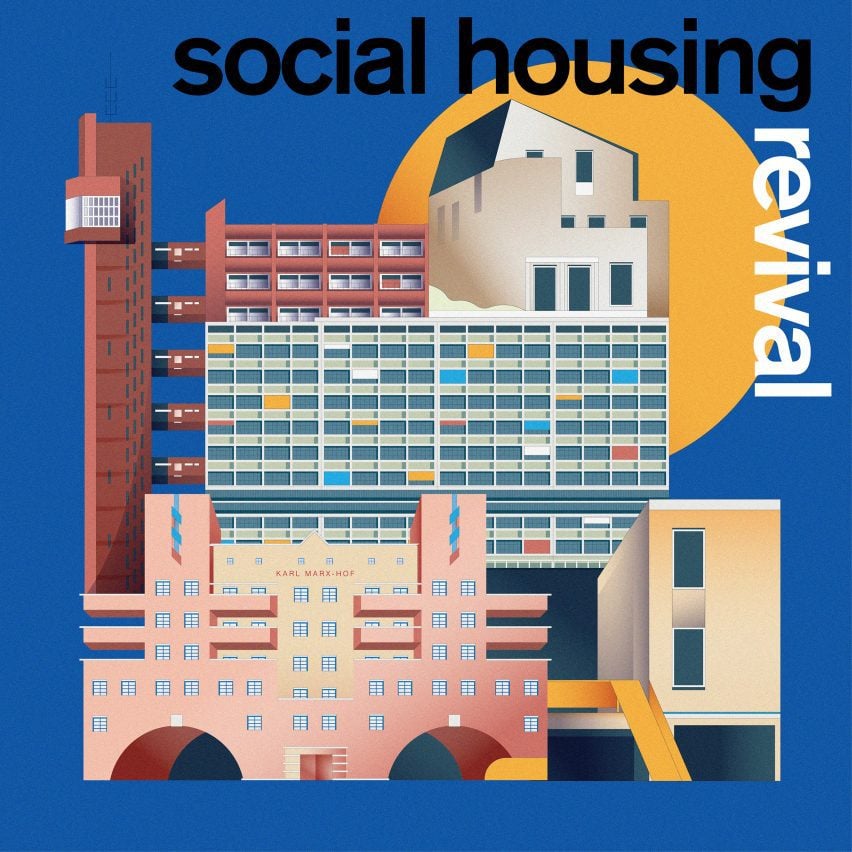

Few cities in the world are grappling with homelessness and a severe lack of housing affordability like Los Angeles. Brooks+Scarpa has built a practice addressing issues in the city and across the nation. For this multifamily residential, The SIX was designed as a 52-unit affordable housing project that “provides a home, support services and rehabilitation for previously homeless and/or disabled veterans.”

Few cities in the world are grappling with homelessness and a severe lack of housing affordability like Los Angeles. Brooks+Scarpa has built a practice addressing issues in the city and across the nation. For this multifamily residential, The SIX was designed as a 52-unit affordable housing project that “provides a home, support services and rehabilitation for previously homeless and/or disabled veterans.”

Over the last two decades, development in China has been defined by a dizzying pace and new architecture produce in-mass. For Jinshan 9, this force behind new buildings was directed into a multifamily living community. Located in China’s Shekou mixed-use district, the project looks out west to wild, forested mountains and east to Shenzhen Bay Bridge. With a range of both low-rise and high-rise structures, the development was made for diverse lifestyles and populations.

Over the last two decades, development in China has been defined by a dizzying pace and new architecture produce in-mass. For Jinshan 9, this force behind new buildings was directed into a multifamily living community. Located in China’s Shekou mixed-use district, the project looks out west to wild, forested mountains and east to Shenzhen Bay Bridge. With a range of both low-rise and high-rise structures, the development was made for diverse lifestyles and populations.

First, it’s important to understand that while all mushrooms are fungi, not all fungi are mushrooms. Mushrooms are the fruiting body of fungi. A mushroom is like an apple growing on an apple tree––it’s the fruit, not the tree. In the fungi world the “tree” is called mycelium. Mycelium is the living body of fungi. It’s a rootlike structure that is constantly eating, expanding, and connecting in large filamentous networks underground or in rotting trees. Mycelium is the star of the MycoHab project and the key to a future of fungi-based materials.

First, it’s important to understand that while all mushrooms are fungi, not all fungi are mushrooms. Mushrooms are the fruiting body of fungi. A mushroom is like an apple growing on an apple tree––it’s the fruit, not the tree. In the fungi world the “tree” is called mycelium. Mycelium is the living body of fungi. It’s a rootlike structure that is constantly eating, expanding, and connecting in large filamentous networks underground or in rotting trees. Mycelium is the star of the MycoHab project and the key to a future of fungi-based materials.