Revolutionizing Urban Living: MicroPolis Offers Affordable Housing Solutions in NYC’s Empty Spaces

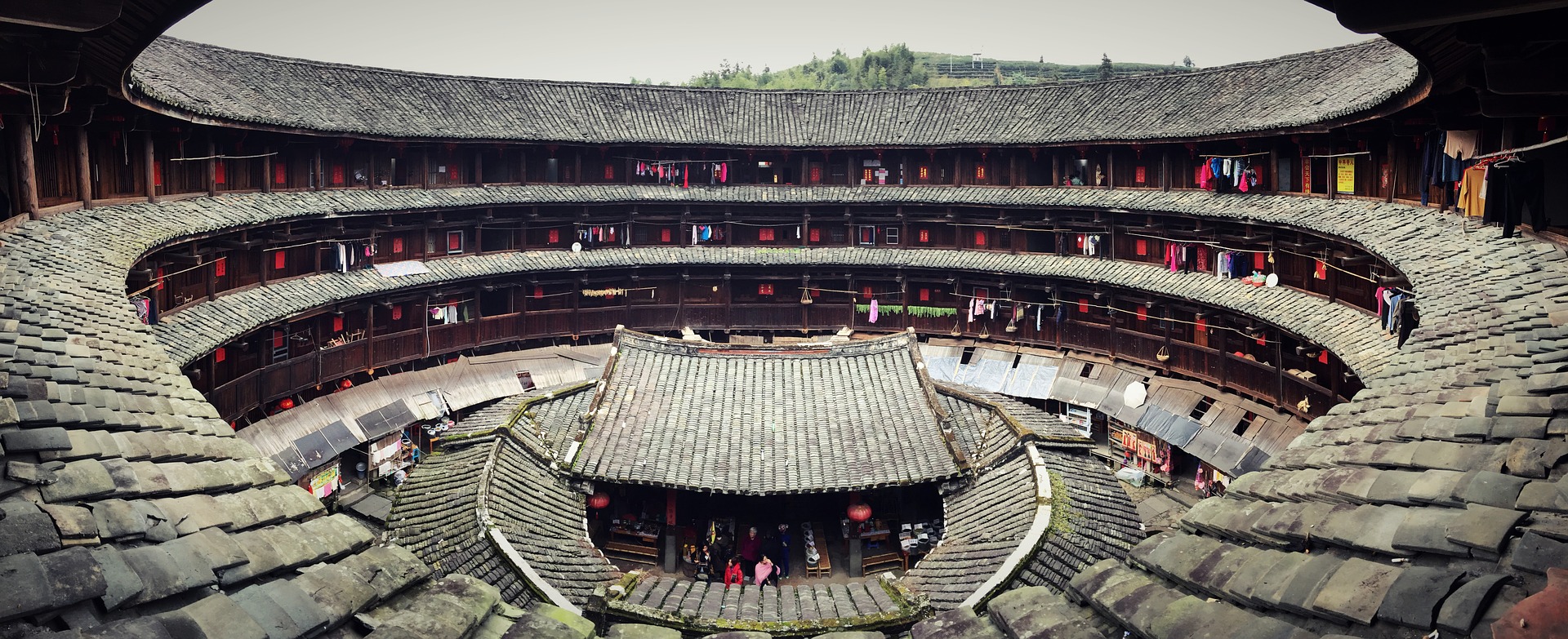

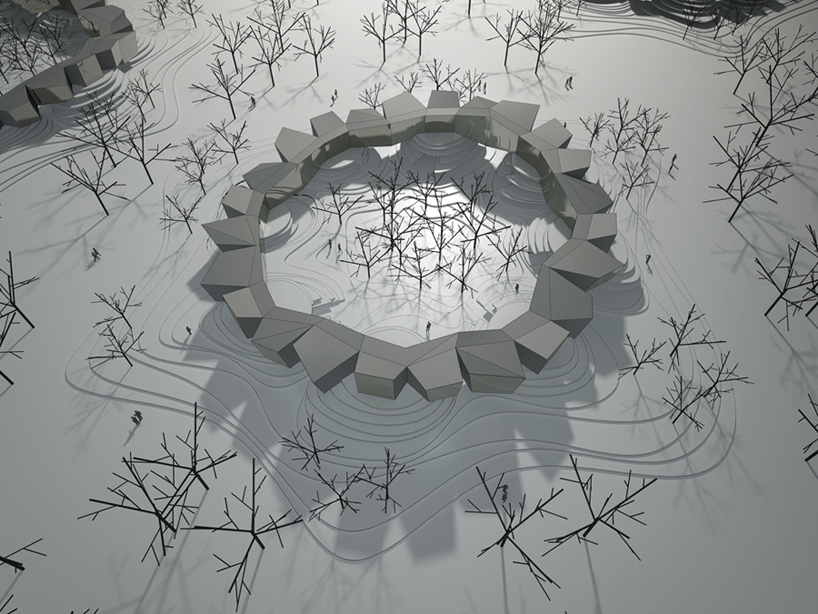

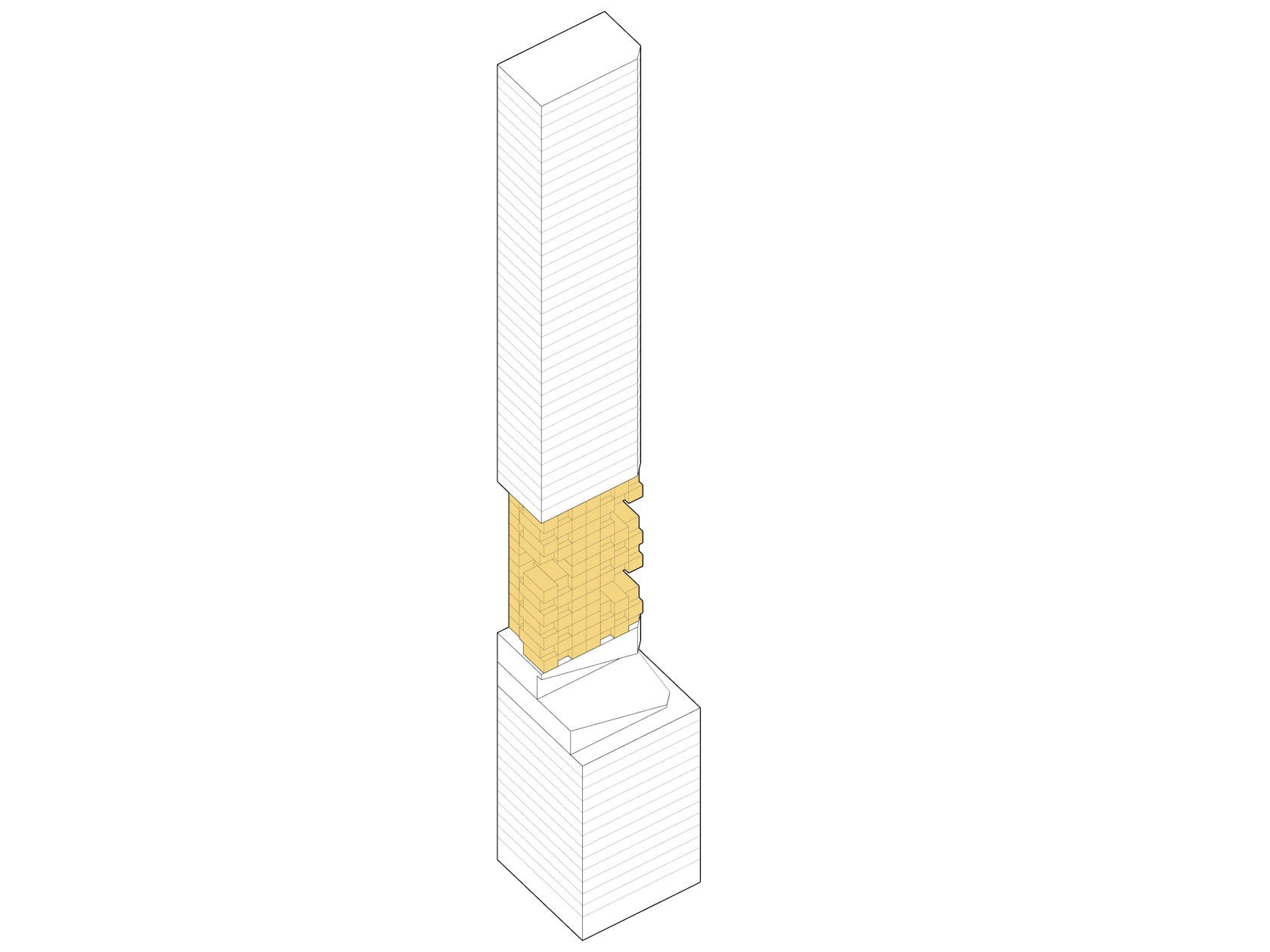

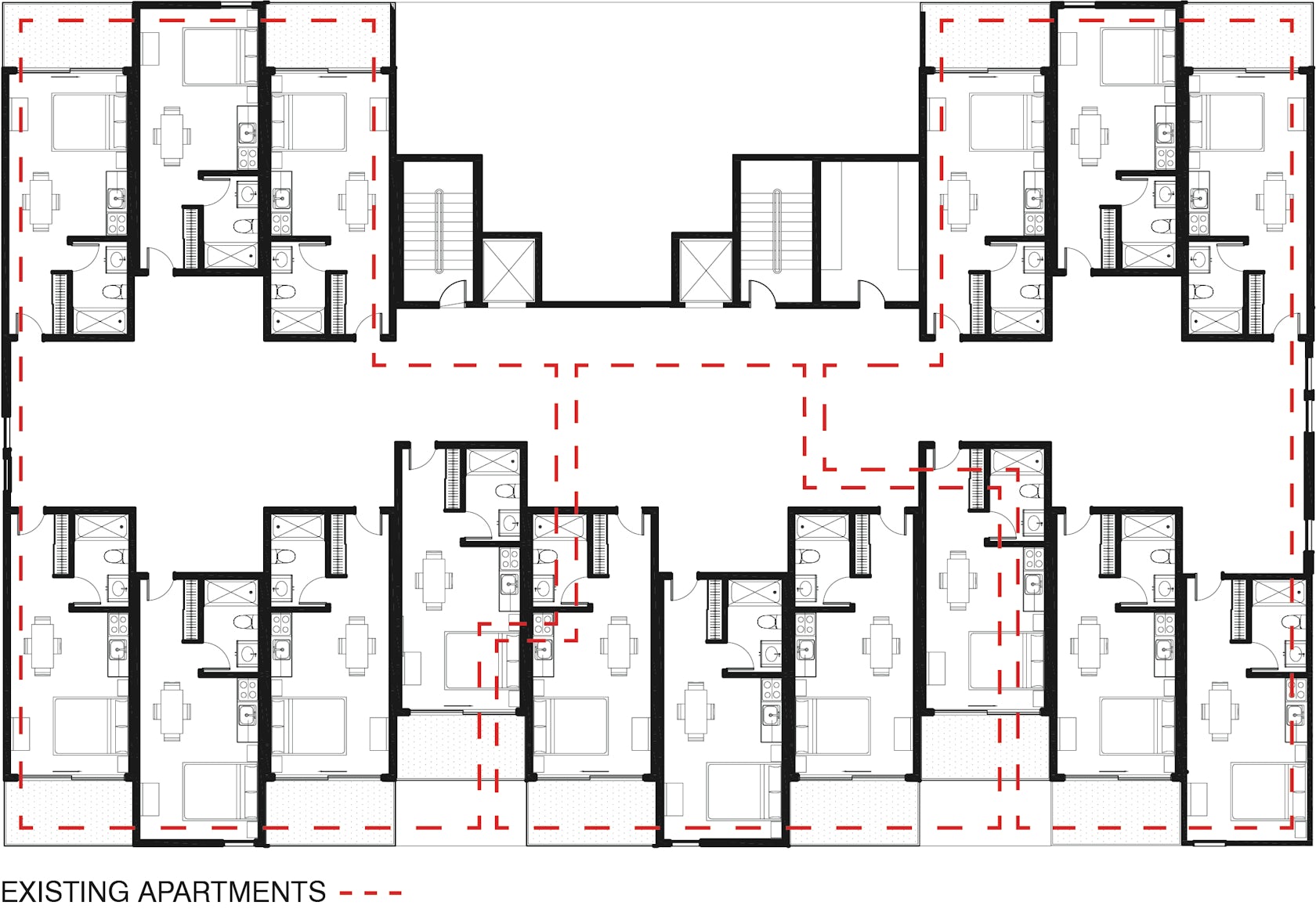

MicroPolis – is a proposal for a new housing typology of micro-homes in metropolitan centers such as New York City. It can be installed in already built, empty urban spaces. The staggering of the units creates a push-and-pull relation, generating balconies for most units. Large public outdoor terraces provide social and co-working spaces and safe places for children to play. Installing these complexes in wealthier neighborhoods and business districts improves living standards for communities of color, immigrant groups, and low- to middle-income families.

Architizer chatted with Esther Sperber, Principal at Studio ST Architects to learn more about this project.

Architizer: What inspired the initial concept for your design?

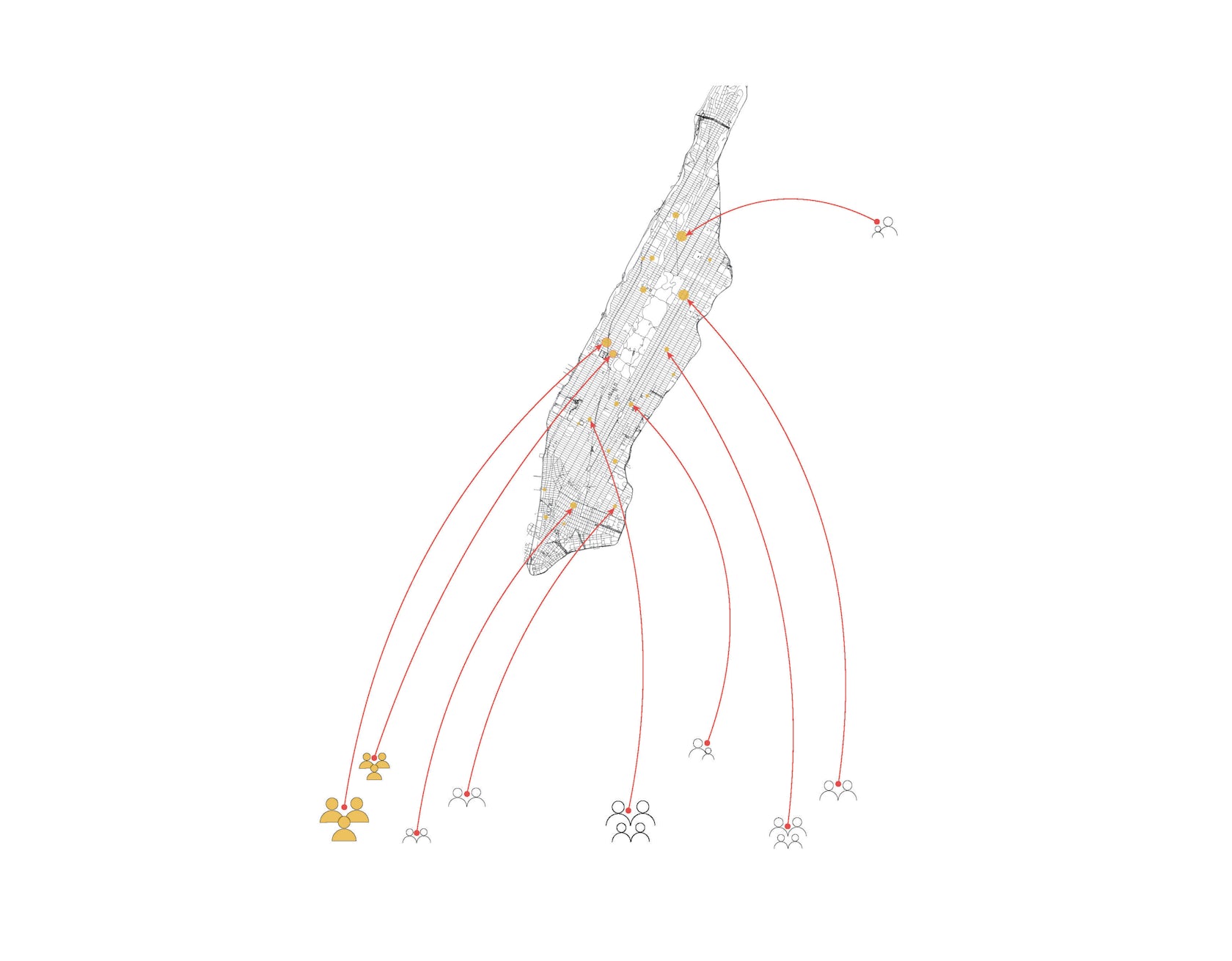

Esther Sperber: MicroPolis is a response to a February 2020 court case that revoked the building permit for the top 20 floors of a Manhattan luxury condominium because it used gerrymandering-style tax lot assembly tactics to justify the request for a very tall building. We suggested that we should not waste these already built floors but rather use them for affordable housing. The aim is to present creative, inclusive and positive design solutions to the urban affordable housing crisis, which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The prevalence of unoccupied and unusable space presents an opportunity to rethink affordable housing throughout the city.

© Studio ST Architects

This project won in the 10th Annual A+Awards! What do you believe are the standout components that made your project win?

The project is contextual and addresses New York City’s critical issues such as the housing crisis, diversity and inclusion, and lowering the carbon footprint in the construction industry. MicroPolis could help alleviate the affordable housing shortage, which we have a moral obligation to address. The design creates innovative, sustainable and affordable micro-homes within vacant floors of luxury buildings in metropolitan city centers. Cities have always embraced people from all kinds of diverse backgrounds, but the pandemic revealed that the city is more divided than we would like to acknowledge. MicroPolis celebrates NYC’s diversity by increasing equity and valuing the range of people needed to make the city thrive. Adding affordable housing units throughout the city’s higher-end neighborhoods aims to make NYC more integrated, resilient and equitable.

© Studio ST Architects

What was the greatest design challenge you faced during the project, and how did you navigate it?

We realize there will likely be resistance to this proposal. Few privileged communities welcome low- and middle- income developments in their neighborhoods, let alone their own apartment buildings. But if we have learned anything during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is that our society is deeply intertwined. The communities that suffered most from the pandemic are those that we depend on most to keep our city running. The same resistance to this project is reason enough to take this typology seriously. It is time to stop averting our gaze from those who are less fortunate economically and invite them to be our neighbors.

© Studio ST Architects

How did the context of your project — environmental, social or cultural — influence your design?

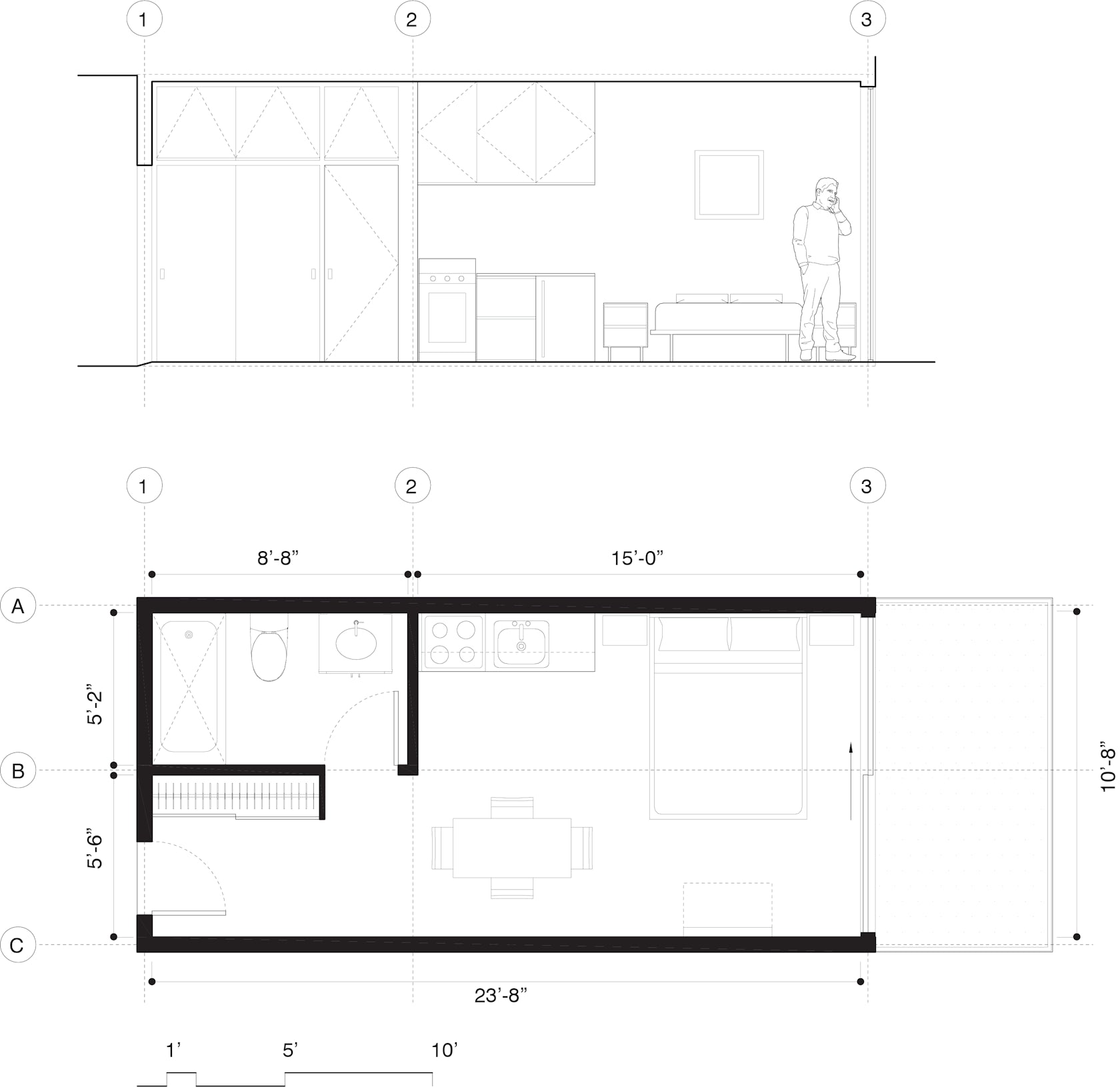

NYC’s real estate exposes the city’s socio-economic inequities. Manhattan’s luxury residential market seems to be rebounding. However, at the same time, the Department of Housing & Preservation, which is responsible for maintaining affordable housing, experienced a 40% cut during the pandemic, resulting in the loss of 21,000 affordable housing units. Our unique modular system, which aims to create greater social equity, consists of prefabricated, energy-efficient and cost-effective micro-homes, which can be installed in already built empty urban spaces. The proposal demonstrates how to creatively house key workers and other tenants in need by maximizing space on mid-level floors of currently unoccupied luxury condos, which some developers have designated as mechanical voids in an attempt to increase the height of luxury buildings and gain maximum value for coveted upper floor apartments.

© Studio ST Architects

How important was sustainability as a design criteria as you worked on this project?

The issue of sustainability was one of the main driving factors of MicroPolis’ design. Reusing built spaces has environmental advantages: it conserves materials and resources, lowers carbon footprint, and brings old, energy-inefficient buildings up to the current code. Carefully selected building materials and cladding ensure thermal insulation to lower energy use and costs for these micro-homes. MicroPolis is also uniquely designed to enable staggered balconies to provide some sun exposure and shade coverage during extreme weather conditions.

© Studio ST Architects

What key lesson did you learn in the process of conceiving the project?

The housing crisis in New York City, or any city for that matter, is a complex issue. With some of the world’s wealthiest residents, New York City is also home to thousands who do not have a clean, warm or dry place to sleep. The city is struggling to address its housing shortage for lower-income individuals and families, and to provide shelter to its 60,000-plus homeless. At the same time, New York City has a record number of empty, unsold, new luxury apartments. Unused space, particularly in tall luxury residential towers, can be reconfigured to accommodate more units dedicated to affordable housing within the existing floor area.

© Studio ST Architects

How do you believe this project represents you or your firm as a whole?

My firm, Studio ST Architects, strives to focus on sustainable, innovative and responsible design. Our firm combines unique expertise in architecture and psychology to design inspiring buildings and renovate spaces that transform human experiences, build deep and inclusive community connections, and create a sense of health and well-being. MicroPolis directly addresses these pillars of our practice.

© Studio ST Architects

How has being the recipient of an A+Award evoked positive responses from others?

It gave us an opportunity to think and explore issues around the multi-family residential typology, particularly within dense urban centers. This also helped us reach a larger audience to raise an issue we are passionate about, which led to more discussions with our clients and collaborators about responsible, compassionate design that addresses not only people’s basic need for housing, but also human connection.

© Studio ST Architects

How do you imagine this project influencing your work in the future?

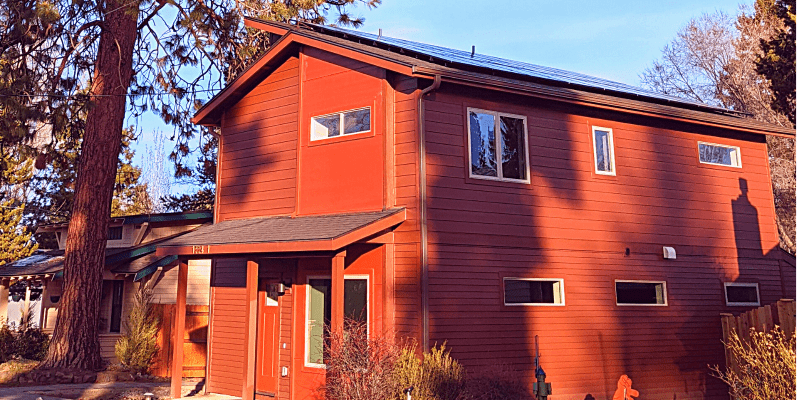

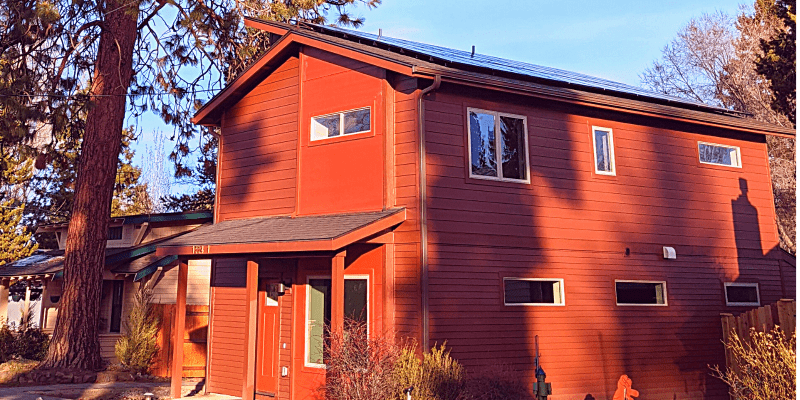

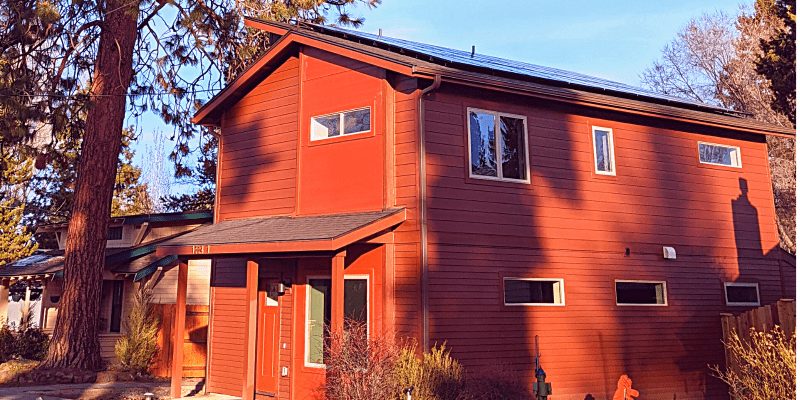

Studio ST Architects has significant experience in apartment interior renovations and religious buildings, but we are excited to do more work in the multi-family residential sector. Our recently completed Jones Street multi-family apartment building holds a similar spirit of ambition to connect people and address the need for housing within Jersey City. Jones Street creates individual homes and a sense of community for the families and young professionals that live in this growing Jersey City community. It targets the swathe of families and young professionals looking for New York-style buildings just across the Hudson River. We hope to continue tackling the housing crisis by taking on more multi-family housing projects.

For more on MicroPolis, please visit the in-depth project page on Architizer.

MicroPolis Gallery

Addressing a high demand for social housing in Mexico City, this project is located on a rectangular plot with its shortest side facing the street. The 42 units are placed in three towers, generating interior courtyards for views and natural ventilation for each apartment, connecting them with vertical cores and bridges above the patios. The masonry brick walls play an important role on the project as they are part of the structure and re-interpret the traditional brick wall, blurring the boundary between structure and ornament. With the use of a single unit; red mud artisanal brick, the team was able to create walls that respond to light and shadow.

Addressing a high demand for social housing in Mexico City, this project is located on a rectangular plot with its shortest side facing the street. The 42 units are placed in three towers, generating interior courtyards for views and natural ventilation for each apartment, connecting them with vertical cores and bridges above the patios. The masonry brick walls play an important role on the project as they are part of the structure and re-interpret the traditional brick wall, blurring the boundary between structure and ornament. With the use of a single unit; red mud artisanal brick, the team was able to create walls that respond to light and shadow.

At the heart of the Flor project was an effort to try and stabilize the lives of people in the city. As permanent supportive housing, the project features large windows, units with a micro kitchen, and each with their own doorbell to reinforce a sense of respite and privacy. Tree-canopied courtyards and indoor and outdoor activity spaces encourage social interaction to add a sense of wellbeing and community.

At the heart of the Flor project was an effort to try and stabilize the lives of people in the city. As permanent supportive housing, the project features large windows, units with a micro kitchen, and each with their own doorbell to reinforce a sense of respite and privacy. Tree-canopied courtyards and indoor and outdoor activity spaces encourage social interaction to add a sense of wellbeing and community.

For La Courneuve, two buildings and 18 duplex units were designed to provide a diversity of housing. A meticulous architectural style contributes to the regeneration of the Cité des 4000. Built in 1956 by the Ville de Paris, this large-scale operation was designed as an estate composed of blocks sited alongside each other. This siting principle generated undefined and unused free spaces, preventing the appropriation of public spaces which are wasted. The regeneration aimed to suppress the effect of uniform and impersonal blocks to give, once again, meaning to the public space with a true landscape and human dimension. The proposal gives a new identity to the neighborhood while integrating this diversity previously missing at all scales of the project.

For La Courneuve, two buildings and 18 duplex units were designed to provide a diversity of housing. A meticulous architectural style contributes to the regeneration of the Cité des 4000. Built in 1956 by the Ville de Paris, this large-scale operation was designed as an estate composed of blocks sited alongside each other. This siting principle generated undefined and unused free spaces, preventing the appropriation of public spaces which are wasted. The regeneration aimed to suppress the effect of uniform and impersonal blocks to give, once again, meaning to the public space with a true landscape and human dimension. The proposal gives a new identity to the neighborhood while integrating this diversity previously missing at all scales of the project.

CasaNova was an exploration that began with a competition publicly announced by the Social Housing Institute based on a Detailed Plan for the residential expansion. This is a tool the municipal administration had to face the need of social housing with a settlement pattern clearly recognizable in the peripheral context. The plan provided the creation of blocks, the “castles”, made of three to four buildings located around an open tree lined court. Following the numerous plan restrictions, the building emphasizes the unity of the plot by working on the concept of block and by identifying a single kind of construction for the front.

CasaNova was an exploration that began with a competition publicly announced by the Social Housing Institute based on a Detailed Plan for the residential expansion. This is a tool the municipal administration had to face the need of social housing with a settlement pattern clearly recognizable in the peripheral context. The plan provided the creation of blocks, the “castles”, made of three to four buildings located around an open tree lined court. Following the numerous plan restrictions, the building emphasizes the unity of the plot by working on the concept of block and by identifying a single kind of construction for the front.

For this innovative project in Paris, the team wanted to embrace the neighborhood. Close to avenue de Flandre and just a stone’s throw from the canal de l’Ourcq, rue de Nantes is a fairly traditional Parisian street of Haussmann and inner-suburb buildings. The project gently inserts itself into a narrow parcel bordered by dense, adjoining housing. On the street side, it extends the building streetscape in a simple manner. On the garden side, the staggering from the 1st to the 6th floors creates large, private, south-facing terraces and allows for an unencumbered view of the sky. The “L” shape and the general volumetrics allowed for the creation of a true, collective garden at the ground level, planted with tall trees.

For this innovative project in Paris, the team wanted to embrace the neighborhood. Close to avenue de Flandre and just a stone’s throw from the canal de l’Ourcq, rue de Nantes is a fairly traditional Parisian street of Haussmann and inner-suburb buildings. The project gently inserts itself into a narrow parcel bordered by dense, adjoining housing. On the street side, it extends the building streetscape in a simple manner. On the garden side, the staggering from the 1st to the 6th floors creates large, private, south-facing terraces and allows for an unencumbered view of the sky. The “L” shape and the general volumetrics allowed for the creation of a true, collective garden at the ground level, planted with tall trees.

Looking to the future, multigenerational house is a social housing located in Wrocław, Poland. The building design combines three functions for three generations: flats with a care service for the elderly and the people with disabilities, flats for rent dedicated for the young and families, and a nursery school on the ground floor. House generates 117 apartments with different typologies. The building is part of the model housing estate Nowe Żerniki, where local architects collectively tried to respond to the growing housing problems and poor spatial quality. One of the initial assumptions of the project was to create a facility conducive to the integration of all its residents and users, so the multigenerational house was designed as a quarter.

Looking to the future, multigenerational house is a social housing located in Wrocław, Poland. The building design combines three functions for three generations: flats with a care service for the elderly and the people with disabilities, flats for rent dedicated for the young and families, and a nursery school on the ground floor. House generates 117 apartments with different typologies. The building is part of the model housing estate Nowe Żerniki, where local architects collectively tried to respond to the growing housing problems and poor spatial quality. One of the initial assumptions of the project was to create a facility conducive to the integration of all its residents and users, so the multigenerational house was designed as a quarter.

The ‘”Gungjeong Social Housing’ project was carried out for a new residential space experiment for the millennial generation of Korean society. For the younger generation in Korea, residential space is turning into a private space and, at the same time, a community space in loosely solidarity with people of similar tastes. They are seeking the possibility of living and sharing various convenient spaces together because of the expensive housing costs in Seoul. In this project, community lounge cafes will be planned for use by residents on the first and second floors, while the remaining three floors will have a shared house that can accommodate a total of 11 people. Four people reside on each floor, and there is a shared kitchen with a high ceiling on the top floor.

The ‘”Gungjeong Social Housing’ project was carried out for a new residential space experiment for the millennial generation of Korean society. For the younger generation in Korea, residential space is turning into a private space and, at the same time, a community space in loosely solidarity with people of similar tastes. They are seeking the possibility of living and sharing various convenient spaces together because of the expensive housing costs in Seoul. In this project, community lounge cafes will be planned for use by residents on the first and second floors, while the remaining three floors will have a shared house that can accommodate a total of 11 people. Four people reside on each floor, and there is a shared kitchen with a high ceiling on the top floor.

Creating a new urban model, the Iceberg development aimed to create an opportunity for Denmark’s second largest city to develop in a socially sustainable way by renovating its old, out-of-use container terminal. Looking to the future while creating a distinct district, the area is comprised of a multitude of cultural and social activities, a generous amount of workplaces, and a highly mixed and diverse array of housing types. The Iceberg Project was designed to work within the goals of the overall city development. A third of the project’s 200 apartments are set aside as affordable rental housing, aimed at integrating a diverse social profile into the new neighborhood development.

Creating a new urban model, the Iceberg development aimed to create an opportunity for Denmark’s second largest city to develop in a socially sustainable way by renovating its old, out-of-use container terminal. Looking to the future while creating a distinct district, the area is comprised of a multitude of cultural and social activities, a generous amount of workplaces, and a highly mixed and diverse array of housing types. The Iceberg Project was designed to work within the goals of the overall city development. A third of the project’s 200 apartments are set aside as affordable rental housing, aimed at integrating a diverse social profile into the new neighborhood development.

Full House by Leckie Studio Architecture + Design, Vancouver, Canada

Full House by Leckie Studio Architecture + Design, Vancouver, Canada

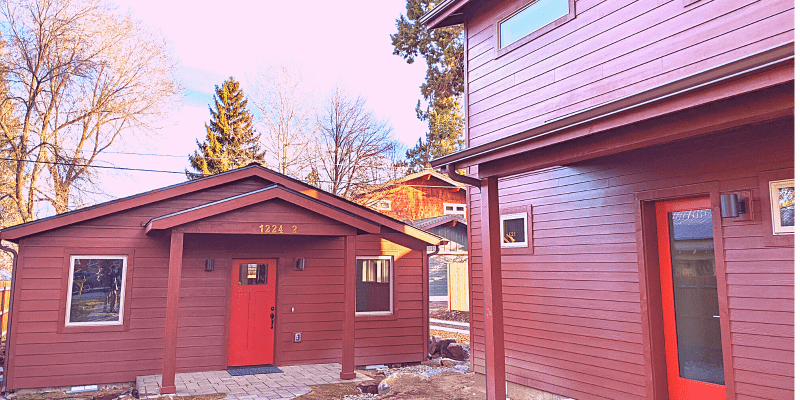

Laneway House by 9point9 Architects, Townsville, Australia

Laneway House by 9point9 Architects, Townsville, Australia

Rough House + Laneway, by Measured Architecture Inc., Vancouver, Canada

Rough House + Laneway, by Measured Architecture Inc., Vancouver, Canada

Laneway Wall Garden House by Donaghy & Dimond Architects, Dublin, Ireland

Laneway Wall Garden House by Donaghy & Dimond Architects, Dublin, Ireland

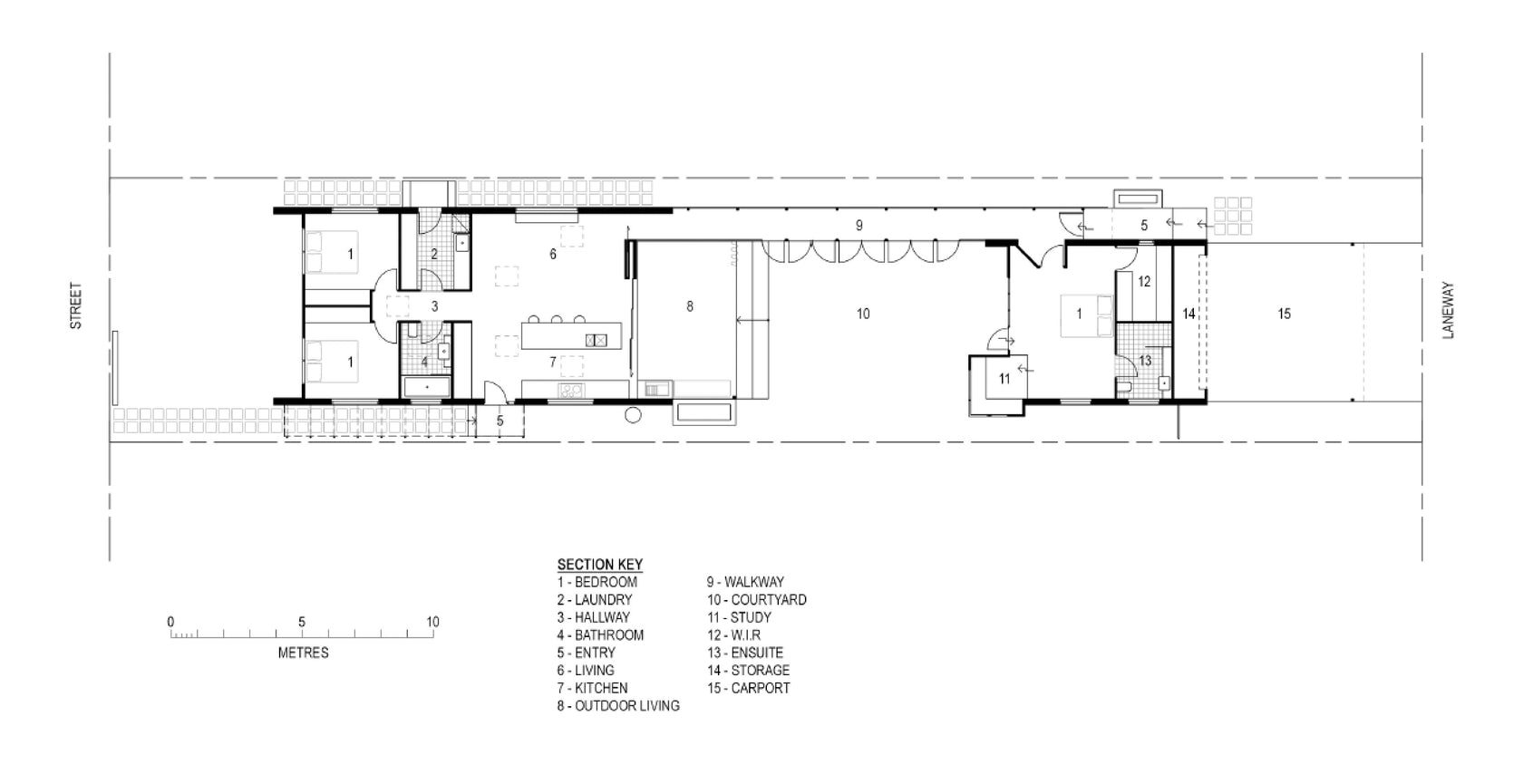

McIlwrick Residences by B.E. Architecture, Melbourne, Australia

McIlwrick Residences by B.E. Architecture, Melbourne, Australia

Riverdale Townhomes by Studio JCI, Toronto, Canada

Riverdale Townhomes by Studio JCI, Toronto, Canada