What’s So Luxurious About Luxury Vinyl Tile, Part III: The Poison Plastic and Why “Recycling Will Not Save Us”

This article was written by Burgess Brown. Healthy Materials Lab is a design research lab at Parsons School of Design with a mission to place health at the center of every design decision. HML is changing the future of the built environment by creating resources for designers, architects, teachers, and students to make healthier places for all people to live. Check out their podcast, Trace Material.

Between 1950 and 2019, more than 7,000 million metric tons of plastic waste were generated. We add roughly 400 million metric tons to that figure every year. If your eyes glazed over while reading these frankly incomprehensible numbers, just know that our plastic waste problem is out of control. Recycling, the solution long promoted by the plastics industry as a panacea, is deeply flawed at best and entirely unfeasible at worst.

So, if recycling as we know it won’t save us, what do we do with the mounds of plastic clogging our waterways and landfills? Even if we could recycle plastics effectively at scale, does it make sense to recycle a toxic plastic like Luxury Vinyl Tile?

This article is Part III of a three-part series on the hazards of vinyl flooring.

- Part I explores the “dirty climate secret” behind the popular material and shares some healthier, affordable alternatives.

- Part II considers the long history of worker endangerment by the vinyl industry and how this legacy continues in China today.

- Part III, this article, explores the dark side of recycling.

The Guilt Eraser

Municipal Solid Waste – Worker in recycling facility, The U.S. National Archives, Library of Environmental Images, (ORD), image via GetArchive

As early as the 1970s, plastics industry officials warned that effective recycling of plastic wasn’t feasible. One said in a 1974 speech that “there is serious doubt that [recycling plastic] can ever be made viable on an economic basis.” And yet, the plastics industry forged ahead with its recycling messaging. Plastic’s enemy number one was the guilt people felt about the wastefulness of single use products. So even if the industry wasn’t actually recycling or protecting the environment, they needed consumers to think that they were.

One industry lobbyist called recycling the great “guilt-eraser”. “Recycling assures people that plastic isn’t just an infernal hanger-on; it has a useful afterlife. As soon as they recycle your product,” he explained, “they feel better about it.”

Throughout the ‘90s, as environmental pushback mounted, the plastics industry fought back. Recycling was their most important message, so they spread it far and wide. The industry spent over $250 million on public campaigns about the usefulness of plastic and its ability to be reused. They wanted people to feel safe and comfortable with their products. They also invested millions in recycling efforts, but those efforts have come up dramatically short. In 2021, the U.S. (by far the world’s biggest plastics polluter) only recycled around 5% of plastics.

We spoke to Kara Napolitano who is the Education and Outreach Coordinator for the Sims Municipal Recycling Center in Brooklyn, New York for an episode of our podcast, Trace Material. We cover the sordid history of plastics recycling and its uncertain future. Kara, who lives and breathes recycling, had this to say about how we should set our plastics priorities:

“My job is to teach people about recycling. But I have to bring attention to the fact that recycling is only halfway up that waste hierarchy of preferred methods for managing our waste. Recycling is not number one. Recycling will not save us. At the very top of that waste hierarchy — the most preferred thing to do to manage your waste — is to not create any waste in the first place.”

Kara reminded us that the well known waste management hierarchy goes: “Reduce. Reuse. Recycle.” If we are to reverse the course of our plastics crisis, we must focus our efforts on drastically reducing production and consumption of plastic all together.

The Poison Plastic

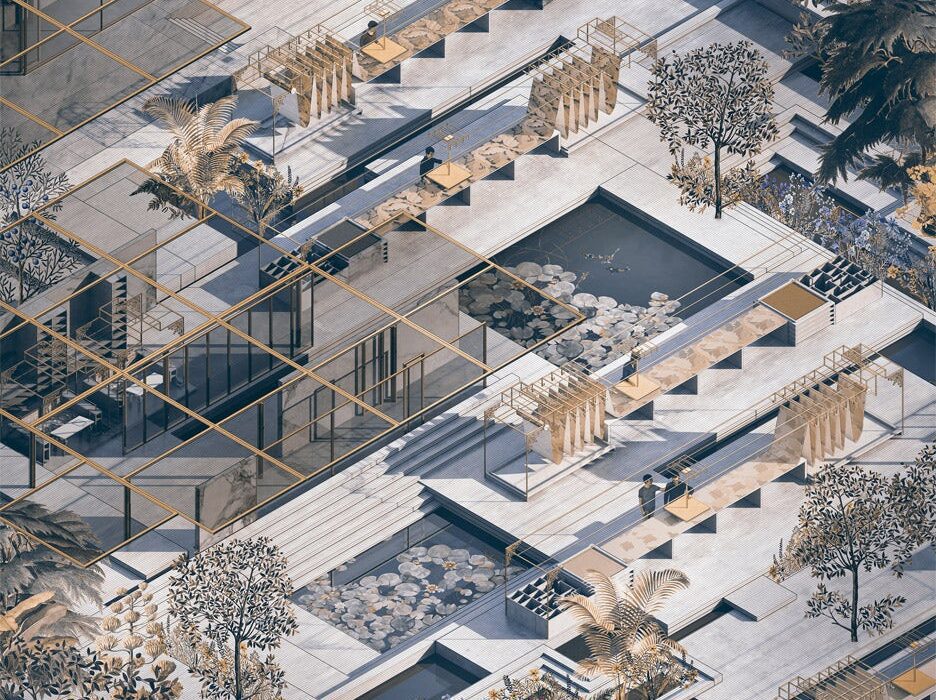

Image generated by Architizer using Midjourney

There are lots of questions that need answering about the future of recycling. While there is consensus that we should focus on reducing plastics production, there are debates raging about what to do with the mounds of plastic we’ve already created. There is, however, no question about PVC’s place in that future. From a health standpoint, PVC has no place in a circular plastics economy.

That’s because PVC is toxic at every stage of its life cycle. The building block of PVC, vinyl chloride, is a known human carcinogen. Then there are performance additives: plasticizers to make PVC flexible can disrupt the body’s endocrine system and heavy metals used to make it rigid are toxic too. These toxic chemicals are in the millions of homes across the country that utilize the number one flooring choice in the US: Luxury Vinyl Tile. And, these dangerous chemicals don’t magically disappear if PVC is recycled. When companies advertise recycled LVT or tout its ability to enter the circular economy, ask yourself: Would I paint my house with recycled lead paint?

Problematic and Unnecessary

The U.S. Plastics Pact is a group of “stakeholders across the plastics value chain” that are trying to create a circular economy for plastics in the United States. To be clear, this group is certainly not anti-plastics nor anti-recycling. Yet, they have labeled PVC plastic to be a “problematic and unnecessary” material and are working to eliminate it from all packaging by 2025. This is because PVC is “not currently reusable, recyclable or compostable with existing U.S. infrastructure at scale” and “contains hazardous chemicals or creates hazardous conditions that pose a significant risk to human health or the environment (applying the precautionary principle) during its manufacturing, recycling (whether mechanical or chemical), or composting process.”

PVC is incredibly difficult to recycle and it interferes with the recyclability of other plastics too. Even if recycling PVC at scale could be figured out, its carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting chemicals remain. These chemicals pose a threat to residents in the use phase and again to humans and the planet at disposal. The vast majority of PVC ends up in landfills and incinerators. When PVC is burned, a host of toxic chemicals, including dioxins, are released into the air, soil and water. While there may be hope for a future where some plastics are able to be effectively recycled at scale, PVC should not and will not be a part of that future.

Rethink, Redesign, Reform

We should continue to support innovations in plastics recycling. Exciting progress is being made in the field of biological recycling, which uses enzymes from bacteria, fungi and insects to break plastics down into their component parts. This allows for theoretically infinite recycling of plastics that could have a smaller carbon footprint than making virgin plastics.

What we should not do is continue to use recycling as a guilt eraser. No innovations in recycling can justify the continued production of materials as toxic as PVC, and therefore LVT. The most effective thing that we as designers and architects can do to protect humans and our planet, is stop specifying plastics (especially PVC) wherever possible. In part one of this series we shared a list of healthy, affordable alternatives to vinyl flooring. You can find other thoroughly vetted flooring options in our materials collection on the Healthy Materials Lab website.

We’ll leave you with a re-imagining of the waste management hierarchy (“reduce, reuse, recycle”) mentioned earlier from Chief Scientist of Environmental Health Sciences and friend of Healthy Materials Lab, Pete Myers:

Re-Think

Many applications of plastics are non-essential. Serious efforts should be made to identify the essential uses of plastics vs. non-essential.

Redesign

Chemists should be given the challenge of creating safer materials to use when the services of plastic are required.

Reform

The regulatory system needs to be reformed by incorporating 21st century biomedical science in its assessments of safety.

As architects and designers our charge as pivotal members of the design and construction industry is to re-think the design decision making process that has been “business as usual” for the last several decades. If we put the health of our bodies, the planet, and all those living there at the center of our design decisions, the way we build will radically change. That thinking has to extend to the entire lifecycle of the materials we use.

If we consider their impact from the time they leave the earth to the time they are returned to the earth, we will have no choice but to re-design our systems of production. These shifts in thinking will leave no place for toxic plastics or any other toxics in our work. Centering human and ecosystem health in design and construction will positively change the future for everyone.

Architizer is thrilled to announce the winners of the 11th Annual A+Awards! Interested in participating next season? Sign up for key information about the 12th Annual A+Awards, set to launch this fall.

Waste is at the forefront of many global sustainable initiatives. Why? Because we all contribute to waste. It is part of our daily lives and, realistically, isn’t going anywhere. Currently, we are running out of space to house our waste. In the US alone, a whopping 292 million tons of trash was generated in a single year. To make room for all this waste, natural habitats have been destroyed, greenhouse gas emissions have risen, and taxes have gone up to offset the costs of running expensive landfills.

Waste is at the forefront of many global sustainable initiatives. Why? Because we all contribute to waste. It is part of our daily lives and, realistically, isn’t going anywhere. Currently, we are running out of space to house our waste. In the US alone, a whopping 292 million tons of trash was generated in a single year. To make room for all this waste, natural habitats have been destroyed, greenhouse gas emissions have risen, and taxes have gone up to offset the costs of running expensive landfills. For some real-world context, Jessica shared a bit on Inpro’s

For some real-world context, Jessica shared a bit on Inpro’s