Animal-centric interspecies design goes “beyond sustainability”

A new design trend prioritises the needs of bugs and animals above human beings. Rima Sabina Aouf finds out if “interspecies design” is the next step in creating more sustainable spaces and objects.

An exhibition designed to invite in animals, a garden optimised for the senses of pollinators rather than humans and architecture designed with nooks in which birds and insects can nestle form part of the novel approach.

“This is a subject that we have been more and more interested in,” the co-founder of London design practice Blast Studio Paola Garnousset told Dezeen.

Blast Studio started out by making 3D-printed structures from waste coffee cups where mycelium – the filamentous part of fungus that has applications as an architectural and design material – could grow.

But as the designers gradually optimised their designs with more folds and interstices that would meet the organism’s preference for darkness and humidity, they found themselves thinking about other species as well.

The studio is now working on an outdoor pavilion whose intricately structured columns will accommodate ladybirds, bees and birds.

“The 3D printing techniques that we use give us the possibility to create artefacts that are designed both at the micro scale of fungi and insects and the macro scale of human beings,” said Garnousset.

Interspecies design about “changing our level of respect” for other creatures

London’s Serpentine Gallery has hosted two projects that centred interspecies approaches in the last two years.

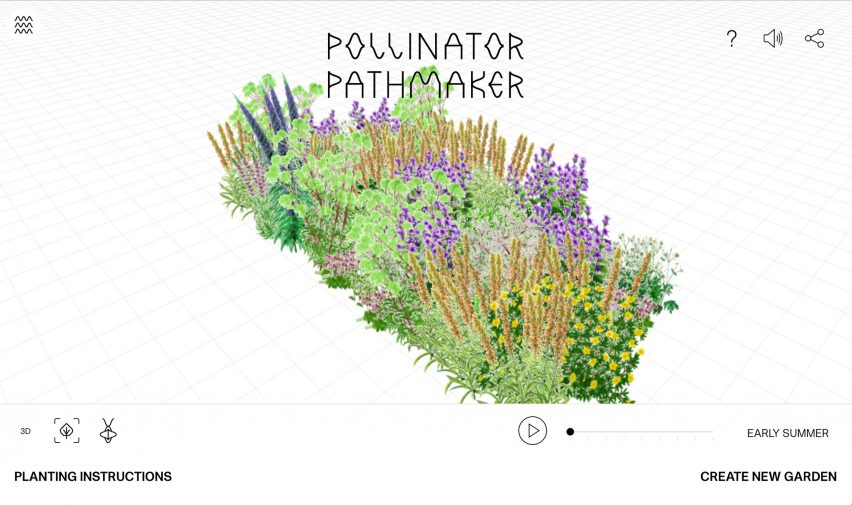

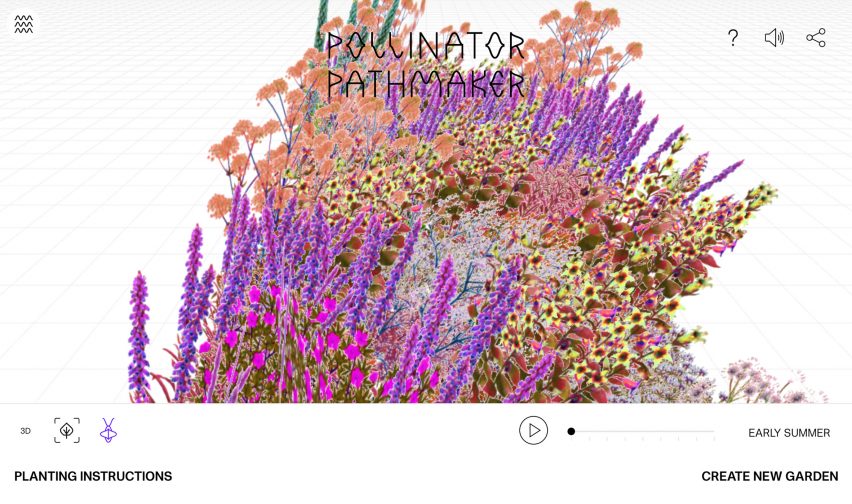

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s Pollinator Pathmaker is an artificial-intelligence-powered tool that designs gardens to be as appealing as possible for bees and other pollinators, while Tomas Saraceno’s Web(s) of Life exhibition involved making several changes to the building so it would be welcoming for the animals and insects of the surrounding park.

Ginsberg considers the interspecies approach to be an attempt to create with empathy for other lifeforms. She came to it after spending several years researching the idea of what it means to make life “better”.

“Exploring how other species experience the world and – in the case of Pollinator Pathmaker – how they experience the things that humans create, opens up a world filled with empathy,” said Ginsberg.

“We need to think beyond sustainability towards prioritising the natural world.”

MoMA’s senior design curator Paola Antonelli has also developed an interest in interspecies design. She suspects the approach has a “very long history” but that it is reemerging in the West in line with the recuperation of indigenous knowledge and the rise of the rights of nature movement, which involves granting legal personhood to entities like rivers and mountains.

“I think that we get closest to real interspecies design when we think like that,” Antonelli told Dezeen. “When we change our level of respect and communication and really try to position ourselves in a different way, not as colonisers but rather as partners in crime, so to say.”

A “process” towards the impossible

True interspecies design, as Antonelli sees it, may be impossible since human designers have a fundamentally human-centric view of the world.

But Antontelli considers the term a useful umbrella for a range of works that call for an “unlearning and learning process”, dismantling the hierarchy that humans uphold between ourselves and other species.

Her version of the canon includes earlier works that attempt to find “a common language” with animals, like Sputniko!’s Crowbot Jenny, for which the designer, scientist and polymath created an instrument in order to communicate with crows.

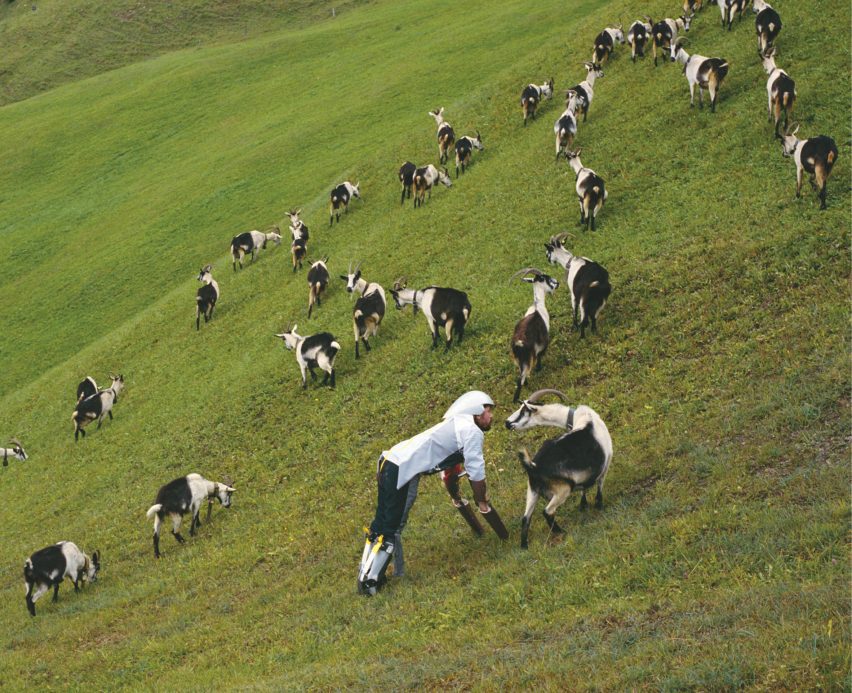

Then there is Thomas Thwaites’ GoatMan project, for which the designer spent three days living as a goat.

While Thwaites told Dezeen he doesn’t consider GoatMan to be a true work of interspecies design – “the impetus of GoatMan was my desire to have a holiday from being a human, so pretty selfish” – he does see the connection.

“Goatman was definitely intended to contribute to a shift in how we think of non-human creatures,” he said. “Goats are just as highly evolved as humans – there’s no hierarchy.”

“I feel that interspecies design is a process,” said Antonelli. “That it goes from designing for animals to designing with animals to – what’s the next step? Enabling animals to design for themselves?

“That would be the real gesture, right? If we were able to actually let go of the tools of production. That’s what I would like to see at some point.”

The thorny status of biodesign

A practice of creating together with organisms as they conduct their natural processes, known as biodesign, is emerging. It includes making mycelium bricks or bacteria-produced textiles.

These objects are created by human and non-human actors together, but different projects treat their creature-collaborators in varying ways.

Antontelli considers Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilions, a biodesign project created in collaboration with silkworms, as one of the closest examples yet to a true work of interspecies design.

Oxman studied silkworm behaviour in detail for the work and ended up finding a way to encourage the caterpillars to lay down their silk in sheets rather than cocoons, creating unusual structures.

In contrast to traditional silk harvesting, the silkworms are not killed during this process but instead caught safely as they metamorphose and left to carry on living.

This level of care and symbiosis make the Silk Pavilions stand out as works of interspecies design, even if, in fact, we can’t know for sure that the silkworms are happy with this arrangement.

Curator Lucia Pietroiusti, who is head of ecologies at the Serpentine Gallery where Saraceno and Ginsberg’s works were presented, thinks the area of biodesign distils a key tension in the budding practice of interspecies design.

“Many completely legitimate, genuine and compassionate attempts to design with more-than-humans at heart also exist within capitalist consumerism, within a chain of production,” she said.

“No matter how you slice it, making more of something new is always going to be making more of something.”

And what is ultimately good for other species is probably that we make as little as possible.

A new look for sustainability

While it can be tempting to conclude that the best design for other species is no design at all, that downplays the role that projects like these can play in changing the way we think about production.

Pietroiusti sees interspecies design as part of an evolution of the idea of sustainability towards something more like “thrivability”, where we design for the planet to thrive, not just survive.

“Sustainability as a notion has been in too close a contact with zero-sum principles – this is sustainable because I do it and then I do something else to offset it,” she said. “In the maths of the planet, that is very rarely the case.”

“Are there situations in which certain projects or initiatives can think more ambitiously than sustainability or than reducing harm, and into ‘can we leave things actually better than they were before?'”

Seven years on from GoatMan, Thwaites believes that while the real shifts to recognise and protect non-human creatures need to come at the legislative level, design can contribute commentary and explore how the change might materialise.

“I hope people will one day look back once the cultural shift has happened and wonder at how we didn’t have interspecies design,” he said. “Like smoking in pubs and all the more important social shifts that have taken place over the decades.”

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.