“Architects are so sheltered in terms of sharing knowledge” says Wendy Perring

Hampshire-based Pad Studio recently completed a post-occupancy study on an eco-house it completed 13 years ago. In this interview, director Wendy Perring discusses the findings.

Architecture practice Pad Studio completed New Forest House in 2010. Over the past year, it has been actively measuring the home’s energy usage.

The studio funded the study itself as a learning exercise. Perring believes the approach should be more common among architects.

“It’s so important, because otherwise, how do we learn?” she told Dezeen. “Architects are so sheltered in terms of their sharing of knowledge.”

“It would be great if it was actually mandatory to collect data from all new houses, that there was a much more joined-up system so that we could just share knowledge about what works and what doesn’t.”

The project was developed for a couple with a large budget who wanted to prioritise sustainability – meaning Perring was given licence to experiment.

“Our clients were very enlightened and they requested a house that treads lightly on the Earth, which totally fitted with our ethos, and I think was one of the reasons why we got the job,” recalled Perring, who undertook the project prior to buying out her business partner and establishing Pad Studio.

“Degree of hoping for the best”

Some of the decisions Perring made were unusual for the time.

“I guess it was a case of putting into practice a lot of textbook research, and maybe there was a degree of hoping for the best,” she said. “But it really did pay off.”

For example, the design focuses on a high level of thermal mass, with a concrete structure preferred to lightweight timber frame.

Thermally massive materials like concrete absorb heat from the sun during the day and store it, slowly releasing the warmth when external temperatures drop.

Perring worked with consultant and Bath University visiting professor Doug King on the thermal mass strategy at New Forest House, which contradicted what many low-carbon architecture advocates believed around the turn of the 2010s.

“At that time there was a lot of debate about thermal mass,” said Perring. “We were reading about all this stuff, but we took a leap of faith in many ways.”

“One of the things that is really fascinating in the post-occupancy data is how flat the temperature differential is. It really does work.”

Timber frame was chosen for the guest annexe, where sporadic occupancy meant quicker heating was considered an advantage.

Slatted shutters over the windows help to control the amount of sunlight – and therefore solar heat gain – entering the house.

Perring’s other major sustainability decision was to take New Forest House’s energy generation mostly off-grid.

A ground-source heat pump – Perring’s preference but out of most clients’ financial reach – provides heating and hot water, meaning the house has no mains gas connection. Its bore holes plunge 100 metres underground.

Back in 2010, the heat pump actually had a larger carbon impact than a gas combi boiler, but the national electricity grid’s decisive shift away from coal in the years since has already led to a significant carbon saving.

A solar thermal system on the building’s roof supports the heat pump’s hot water provision.

In addition, 47 solar panels next to the house generate an average of 9,500 kilowatt-hours (kw/h) per year – equivalent to £3,420 at today’s prices.

Solar battery storage with 13.5 kw/h of capacity now being installed on the site will ensure that more of the energy generated can be put to use.

Up to 97 per cent cheaper to run

The post-occupancy energy efficiency study was conducted in collaboration with Mesh Energy Consultants. Five Purmetrix sensors were positioned around the home for 12 months, gathering data on humidity, temperature and ventilation.

They found that, as a result of the sustainability measures embedded into its design, New Forest House is 42 per cent cheaper to run than a home built to current building regulations.

If it wasn’t for the household’s unusually high electricity usage – with an electric pottery kiln, an infrared sauna, electric woodworking tools and an electric car – the house would be 97 cheaper to run compared to most new-builds being constructed today.

Combined, the heat pump and solar mean New Forest House has emitted 110 per cent less carbon dioxide during its lifetime than if it had been powered by gas.

As well as operational efficiency, the study also looked at embodied carbon – that is, emissions caused by the building’s construction.

It concluded that at 359 kilograms of CO2 equivalent per square metre (kgCO2e/m2), New Forest House has an embodied carbon value 43 per cent smaller than set by current building regulations and the Royal Institute of British Architects’ 2030 Climate Challenge.

This is despite the importance of embodied carbon only becoming properly understood in the past few years.

“We weren’t talking about embodied carbon back then – we didn’t have the label – but we knew that we wanted to steward resources carefully,” said Perring.

Local materials were used where possible, while in another unusual step for the time, the concrete has a high proportion of ground granulated blast-furnace slag instead of highly polluting cement.

“We thought: ‘well, if we’re building using concrete, why don’t we just be honest about that fact and actually try to reduce the environmental impact of it, and exploit the fact we’ve got this thermal mass and use it to its benefit’,” said Perring.

“I think architects are very judgmental, in terms of: concrete is bad, timber is good. And that’s not always the case. It’s how you use it.”

Earth berm and swimming pond

Initially she had wanted to use stabilised rammed earth taken from the site for the structure, but testing revealed the soil was unsuitable.

Instead, earth excavated for a basement and swimming pond was saved from landfill by being used for a berm on the northern side, providing added insulation and acoustic shielding from a nearby motorway.

Home to a small community of voles, it is among multiple interventions on the large site intended to contribute to the local ecology, alongside a green roof and the planted swimming pond, which attracts news, grass snakes, kingfishers and nightjars.

As the New Forest is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest, this was essential for gaining planning permission.

The earth sheltering does come with downsides, however. The sensors picked up high humidity levels on this side of the house, increasing the risk of mould growth.

Meanwhile, for most of the year the house’s water is supplied by a restored seepage well that takes from the groundwater.

Wastewater is then treated on-site and filtered back into the landscape before being drawn up by the well again.

“We have to be designing for longevity”

For Perring, circularity is the next major step towards architecture becoming more sustainable, with demountable structures and recyclable materials key aspects of design.

“It’s not acceptable to knock down a house and send it off to landfill,” she said. “We have to be designing for longevity, but we have to be considering what happens, inevitably, to those buildings that do have a defined lifespan.”

In the past 13 years, Pad Studio’s practice has moved on from New Forest House.

A greater range of insulation and window systems are available, Perring explains, while current projects target a considerably smaller embodied carbon.

Its recently completed The Clay Retreat, for instance, has a calculated embodied carbon of 159 kgCO2e/m2 – 56 per lower than New Forest House.

New Forest House’s energy performance remains impressive compared to most houses being built today, but Perring believes that is partly a function of policy failures in the UK.

“I am a big believer that the only way to push things forward is statutory change,” she said.

“There’s got to be better joined up policies in terms of the government setting standards for embodied carbon and operational energy, there’s just got to be.

“We’ve got to use less, we really do.”

The photography is by Richard Chivers unless otherwise stated.

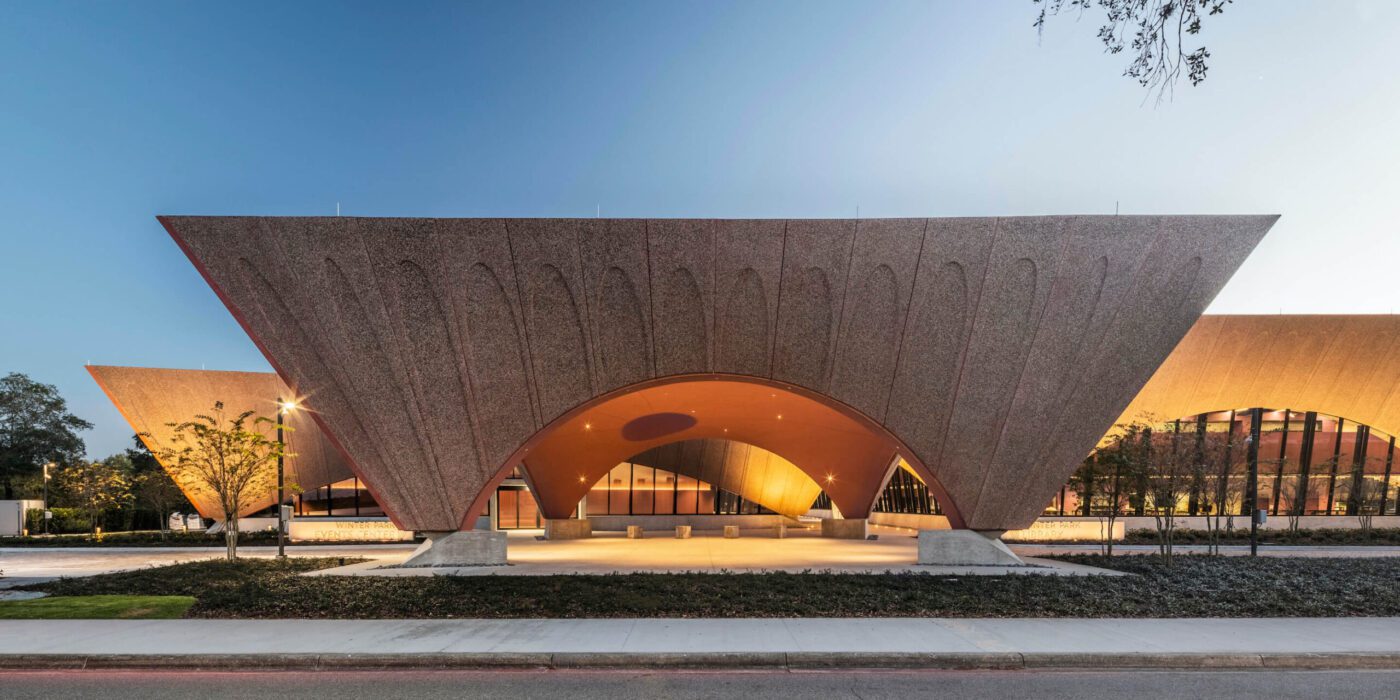

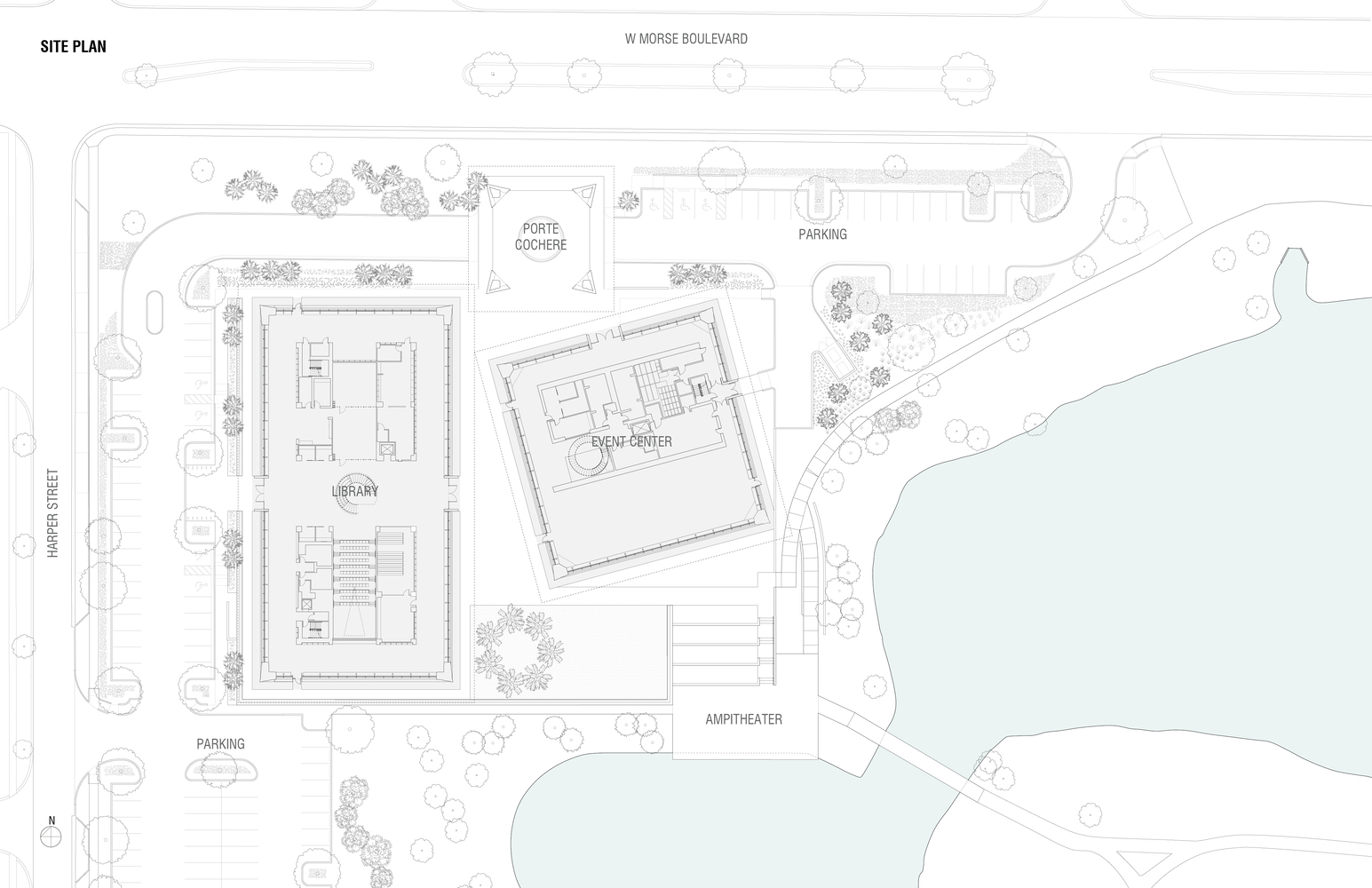

The library’s design team aspired to establish a new civic and cultural hub on the northwest corner of Martin Luther King, Jr. Park in Winter Park, Florida. The library was made to embody the values of the park’s namesake as a space for community empowerment. Seven years in the making, the project spans 50,000 square feet across a trio of canted pavilions.

The library’s design team aspired to establish a new civic and cultural hub on the northwest corner of Martin Luther King, Jr. Park in Winter Park, Florida. The library was made to embody the values of the park’s namesake as a space for community empowerment. Seven years in the making, the project spans 50,000 square feet across a trio of canted pavilions.

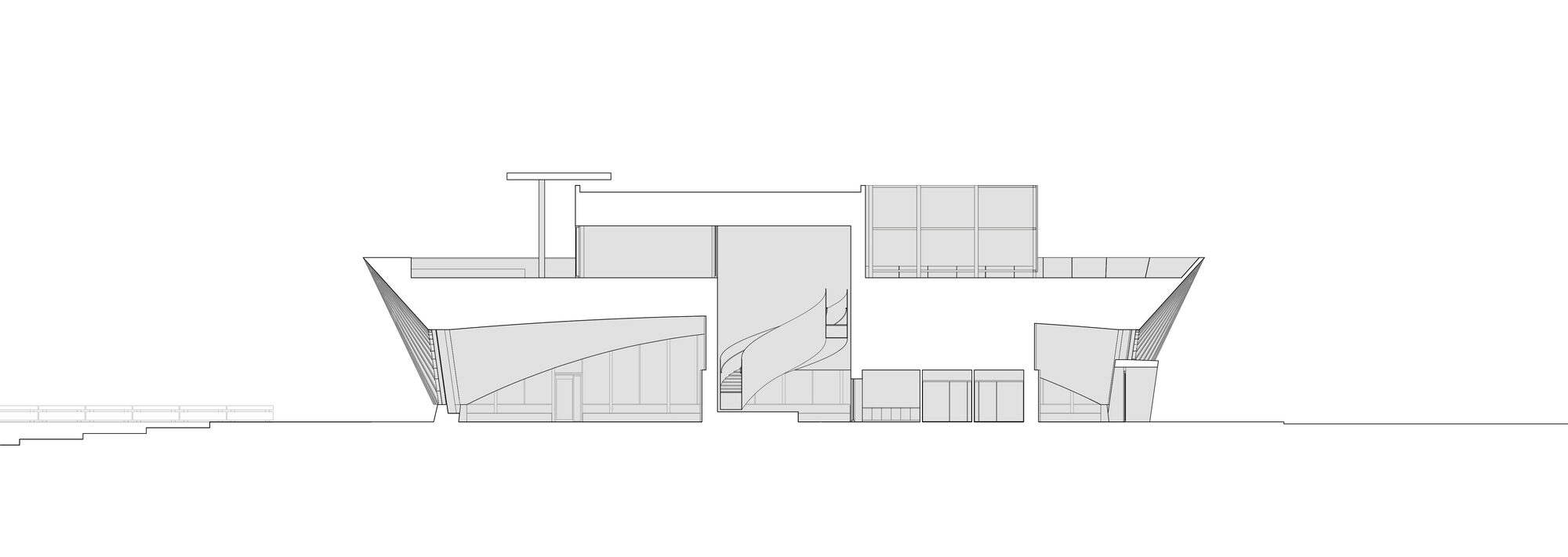

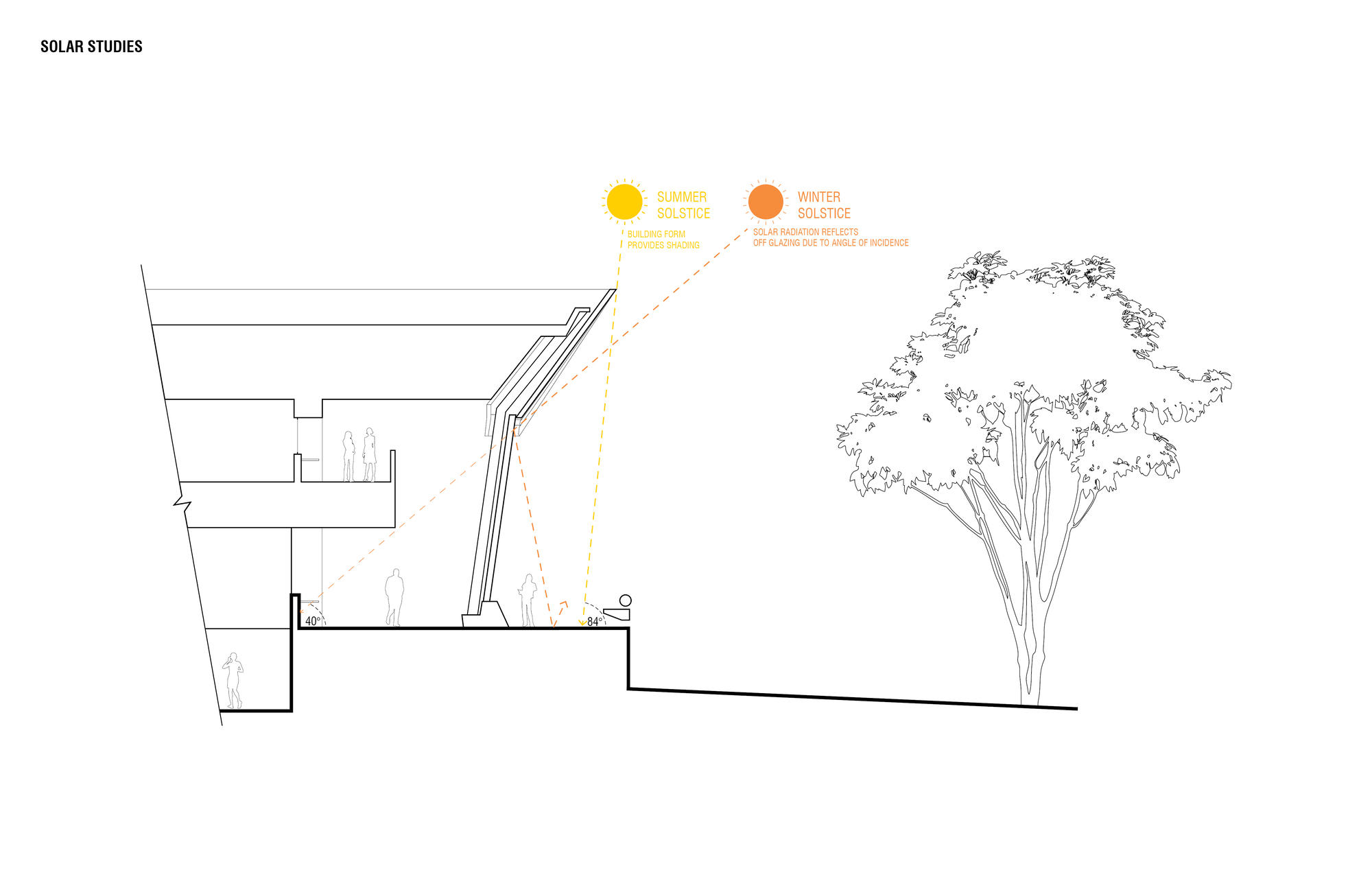

Arches establish the form of the pavilions, where compound, convex exterior walls are made with a series of scalloping, frond-like patterns. The volumes of the library, events center, and porte cochère come very close to touching. Hoping to draw light deep into the new library, the team created the angled exterior walls that lean outward as they rise from the base.

Arches establish the form of the pavilions, where compound, convex exterior walls are made with a series of scalloping, frond-like patterns. The volumes of the library, events center, and porte cochère come very close to touching. Hoping to draw light deep into the new library, the team created the angled exterior walls that lean outward as they rise from the base. For the precast façade, it was determined that concrete was the only cladding material that could achieve the quality and durability needed for the exterior walls. The texture, color, aggregates and concrete matrix were carefully selected for aesthetics, durability and low maintenance. The curved walls are realized with back-up framing made up of structural steel.

For the precast façade, it was determined that concrete was the only cladding material that could achieve the quality and durability needed for the exterior walls. The texture, color, aggregates and concrete matrix were carefully selected for aesthetics, durability and low maintenance. The curved walls are realized with back-up framing made up of structural steel. In turn, a series of sloping, arched curtainwalls in the enclosed buildings meet the curved, solid surfaces. The architects mirrored the concrete edge to create continuous seating along the curtain wall. Shallow foundations are used to support the building loads, while the elevated floor and roof are framed using structural steel beams and girders.

In turn, a series of sloping, arched curtainwalls in the enclosed buildings meet the curved, solid surfaces. The architects mirrored the concrete edge to create continuous seating along the curtain wall. Shallow foundations are used to support the building loads, while the elevated floor and roof are framed using structural steel beams and girders.

The site’s physical constraints required efficient use of space for the buildings, the belvedere and parking. The team worked with

The site’s physical constraints required efficient use of space for the buildings, the belvedere and parking. The team worked with

The library has become a place where the entire community can interact, learn and gather. Inside, open spaces are framed by four timber-lined cores that contain Winter Park’s historical and archival collection spaces, support zones, and private reading rooms. Designing with the community in mind, the event center was made with a flexible auditorium space and a rooftop terrace that offers views of the lakeside park setting.

The library has become a place where the entire community can interact, learn and gather. Inside, open spaces are framed by four timber-lined cores that contain Winter Park’s historical and archival collection spaces, support zones, and private reading rooms. Designing with the community in mind, the event center was made with a flexible auditorium space and a rooftop terrace that offers views of the lakeside park setting.