Human Material Loop sets out to commercialise textiles made from hair

Dutch company Human Material Loop is using an unusual waste source to make a zero-carbon wool alternative that requires no land or water use: human hair.

Human Material Loop works with participating hairdressers to collect hair cuttings, which it processes into yarns and textiles and sometimes turns into garments.

Founder and CEO Zsofia Kollar was initially interested in human hair from what she describes as a “cultural and sociological” perspective before she began exploring its material properties.

“Delving into scientific studies about hair revealed not only its unique characteristics but also the stark reality of excessive waste generated,” Kollar told Dezeen. “This realisation became a catalyst for a clear mission: finding sustainable ways to utilise hair waste.”

Elsewhere, human hair mats are being used to mop up oil spills and to create biodegradable stools, but Kollar honed in on the textile industry as the best target for her aspirations.

“Not only is the textile sector one of the largest markets in our economy, but it also ranks among the most environmentally taxing industries,” said Kollar.

“Throughout history, we’ve utilised a variety of animal fibres in textiles, yet our own hair, composed of the same keratin protein as wool, often goes overlooked,” she continued. “Why not treat human hair as we would any other valuable textile fibre?”

According to Kollar, the use of human hair eliminates one of the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the textile industry: the cultivation of raw materials like cotton plants or farming of sheep for wool.

Waste hair does not degrade any soil, require any pesticide, pollute any water or produce any greenhouse gas emissions, she points out.

At the same time, hair has properties that make it highly desirable. It’s flexible, it has high tensile strength, it functions as a thermal insulator and it doesn’t irritate the skin.

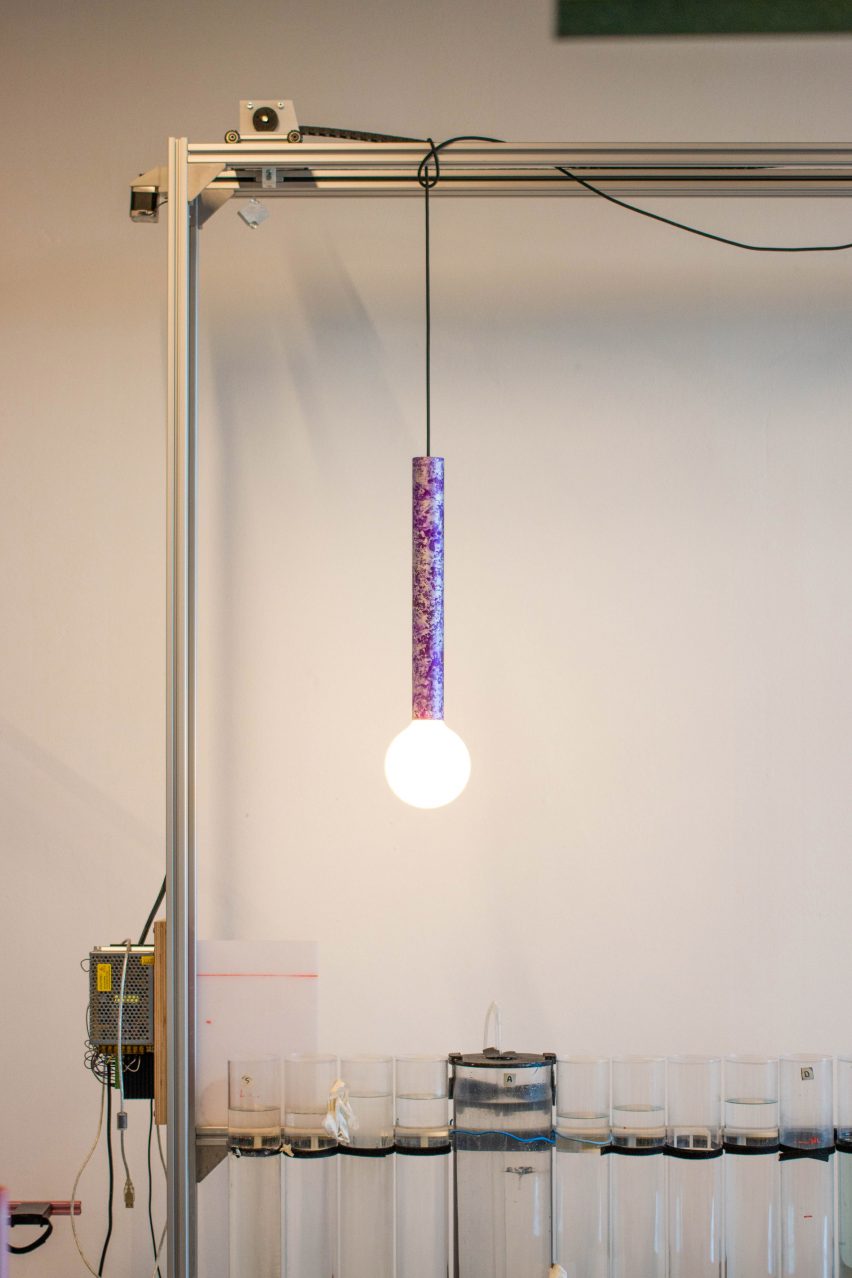

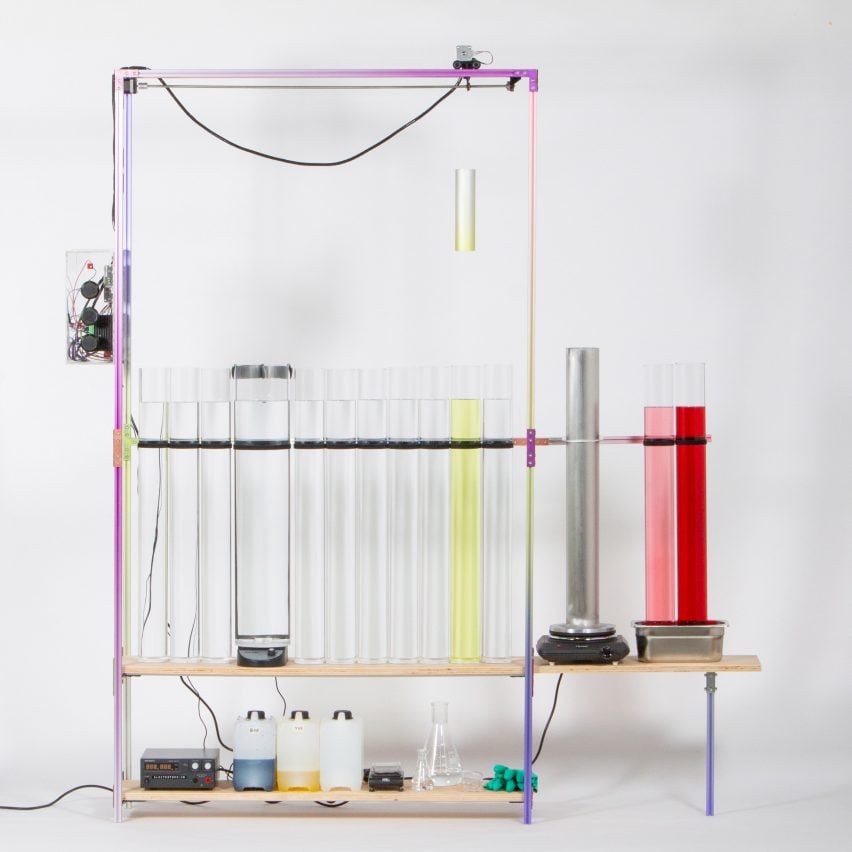

Human Material Loop has focused on developing the technology to process hair so it can be integrated into standard machinery for yarn and textile production.

The company has made the waste hair into a staple fibre yarn – a type of yarn made by twisting short lengths of fibres together – and has several textiles in development.

It has also made a few complete garments, most recently a red sweater-like dress created in collaboration with the company Henkel, owner of the Schwartzkopf haircare brand.

The dress is intended for display at hairdressing events, as part of an initiative to foster discussion about alternative salon waste-management ideas.

Seeing completed products like these, Kollar said, helps to ease the discomfort or disgust that many people feel around using products derived from humans.

“Surprisingly, the material looks utterly ordinary, akin to any other textile,” she said. “A fascinating transformation occurs when individuals touch and feel the fabric. Their initial scepticism dissolves, giving way to a subconscious acceptance of the material.”

“The rejection usually stems from those who’ve merely heard about it without ever laying eyes on the garments themselves,” she continued. “It’s a testament to the power of firsthand experience in reshaping perceptions”

Kollar says Human Material Loop will also be targeting the architecture and interiors products market, for which she believes hair’s moisture resistance, antibacterial properties, and acoustic and thermal attributes will make it an attractive proposition.

The company has a commercial pilot scheduled for 2024 and also aims to create a comprehensive fabric library for brands and designers.

Kollar had been making experimental textiles like a golden, scented tapestry woven from blonde hair for many years before setting out to commercialise the venture with Human Material Loop in 2021.

She is not the only designer to have attempted to utilise wasted hair cuttings. In recent years, Ellie Birkhead incorporated the material into region-specific bricks and hair was used to measure urban pollution in Bangkok.