Bamboo will “be a major player” in architecture says Chris Matthews

The strength and availability of bamboo give it the potential to be as dominant in construction as concrete and steel, argues Atelier One engineer Chris Matthews in this interview.

“This idea that we have a sheet of rigid, extremely polished buildings, built from all kinds of steel and concrete, it has to change,” Matthews told Dezeen.

“Bamboo has a real part to play as a low-carbon material, and it needs to be part of the toolkit that we have moving forward,” he continued. “It’s going to be a major player.”

“The speed of growth is amazing”

Matthews spoke to Dezeen from the London office of British engineering firm Atelier One, where he is an associate director specialising in structural bamboo.

Bamboo is an extremely fast-growing species of giant grass that grows abundantly, quickly and cheaply around the world. Atelier One believes so much in its potential to become a dominant construction material that it has a team dedicated to its use in architecture.

While wood takes approximately 30 years to grow before being harvested as structural timber, a bamboo culm takes just three years.

“The speed of growth is amazing,” Matthews explained. “And the other wonderful thing is that you can grow bamboo on degraded land,” he continued.

“Land that wouldn’t otherwise be being used, you can actually regenerate using bamboo.”

Another key property of bamboo is that it is incredibly strong. In fact, its strength is comparable to aluminium, Matthews said.

“People always say it’s as strong as steel – it’s not as strong as steel, it’s close to aluminium,” Matthews said. “It is also actually stronger than concrete,” he continued.

“So in terms of structures, there’s no reason why you can’t use it.”

Locking carbon in buildings “the way forward”

Yet for Matthews, one of the characteristics of bamboo that makes it most attractive for the future of architecture is that it is an effective carbon store.

Similarly to timber, it sequesters carbon as it grows. In fact, there is even ongoing research to suggest that the material stores more carbon than timber, Matthews highlighted.

“There’s no kind of definitive paper on this yet because it’s such a hard thing to measure, but some papers say it’s between two and six times as much [sequestered carbon],” he said.

“It’s a great way of taking carbon out of the environment and making sure it doesn’t get re-released.”

As with many other advocates of sustainable materials, Matthews believes that the architecture and construction industries must urgently turn focus to the use of biomaterials such as bamboo to design buildings that sequester carbon, rather than expel it.

“In general, the idea of bio-based materials where we are capturing carbon and locking it up in a building, that has to be the way forward,” he said.

“So instead of thinking of a building as something that we have to use up our carbon budget to make, we’re instead thinking of the building as a way of locking up some carbon over the lifetime of the building,” he added. “I hope more and more of that will happen.”

Atelier One now testing structural limits of bamboo

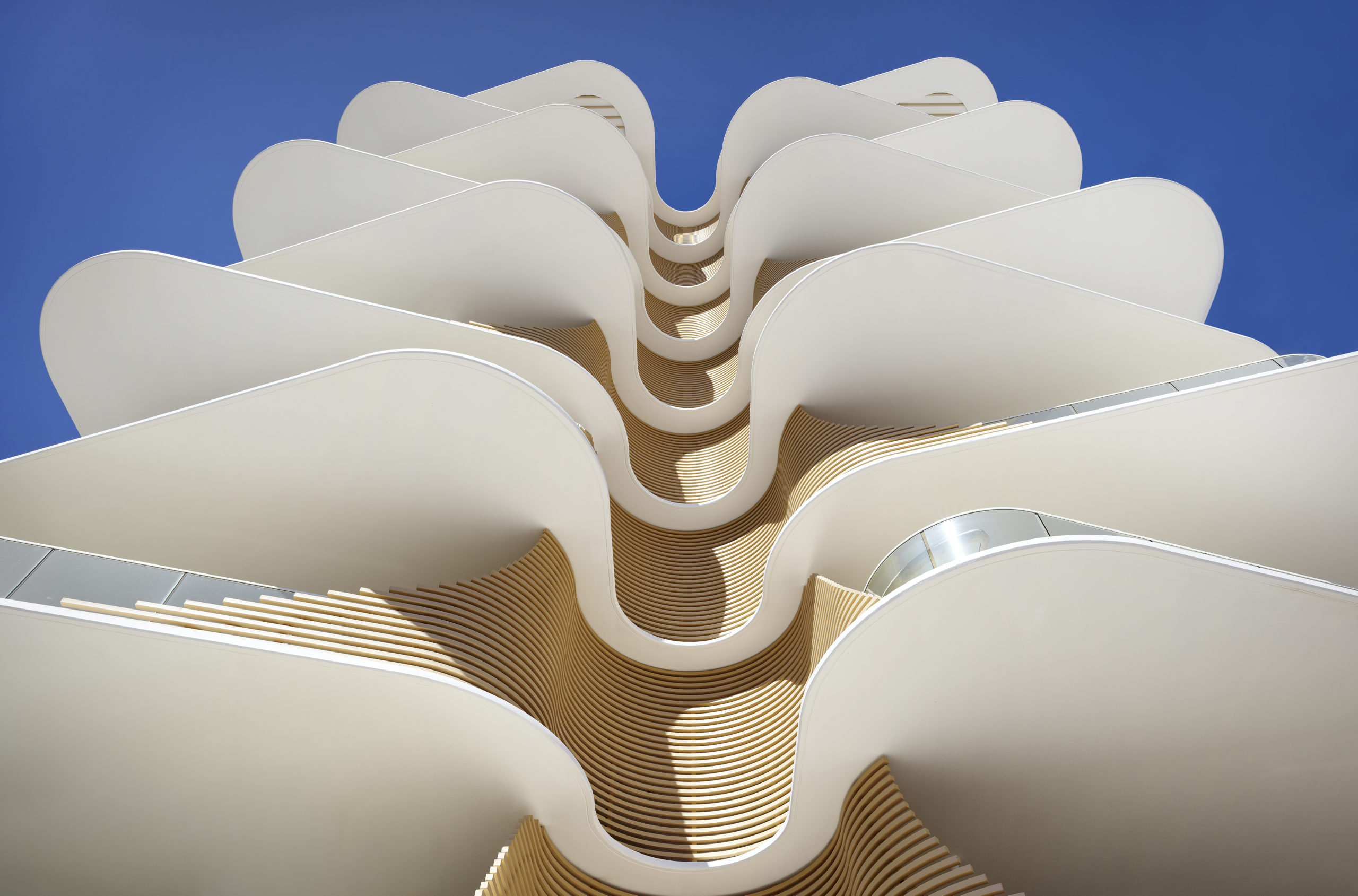

Atelier One’s interest in bamboo was sparked by its founder Neil Thomas’ involvement in The Arc, a bamboo gymnasium at the Green School Bali designed by architecture studio Ibuku.

The sculptural building, which was highly commended in the 2021 Dezeen Awards, is distinguished by its complex double-curved roof made entirely from tensioned bamboo.

“The school has shown that, whereas bamboo was once seen as a ‘poor man’s timber’, actually, the beauty of the structures that result really is amazing,” reflected Matthews.

He argued that it also demonstrates it is possible to overcome the main disadvantage of the material, which has previously been a susceptibility to insect and fungal attacks, which in turn reduces its longevity.

This is achieved by ensuring the bamboo is not exposed directly to the sun, water or the ground. The bamboo is also treated to remove starch to help prevent these attacks, said Matthews.

“The issue has been that [bamboo is] prone to fungal attack and insect attack,” he said. “You’ve now got a material that not only has this amazing speed and strength, but it’s also able to have longevity as well.”

Today, Atelier One’s focus is primarily on maximising the strength and structural capabilities of bamboo, specifically through 3D-printed connections to link culms together.

“So you’ve got this amazingly strong material and now what we’re trying to play with is how you actually get the full strength out of it,” Matthews said. “It’s all about the connections.”

“We’ve started playing with 3D-printed connectors to link pieces of bamboo and get a longer piece of fabric. Once you start playing with the shapes, there’s no end to the possibilities.”

Laminated bamboo “seems to be performing better than timber”

The team is also exploring the potential of laminated bamboo – engineered bamboo products typically formed of layers of bamboo glued, stacked and pressed together.

According to Matthews, laminated bamboo can be used in the same ways as cross-laminated timber (CLT) but actually outperforms it in terms of strength.

“You don’t just have to use the crops whole and unprocessed, there is a whole industry of laminated bamboo,” Matthews said.

“Laminated bamboo actually seems to be performing better than timber, and also just like timber you can encapsulate it, so you put plasterboard on if you need to, it can be used as part of a build-up.”

“People are doing it, it’s early days, but the properties are amazing,” he added. “And it’s really starting to take hold.”

Among the varieties of engineered bamboo are scrimber, cross-laminated timber-bamboo (CLTB) and a type of radial laminated bamboo called Radlam.

The latter is Atelier One’s favourite, Matthews said, as it is processed in a way that retains all the layers of a bamboo culm, reducing waste and maximising strength.

“The reason we like this is because you get the whole culm, so the whole thickness of the bamboo – you’re not wasting material as you process it,” he said.

“And also, by not passing off the outer skin, you’re getting the full strength,” he continued. “It’s three times stronger than standard timber, so the properties are amazing.”

Another advocate for bamboo is Vietnamese architect Vo Trong Nghia. In an interview with Dezeen, he described the material as the “green steel of the 21st century”.

“I think bamboo and laminated bamboo will replace other materials and become the ‘green steel’ of the 21st century,” said Nghia.

“I hope many architects realise the potential of the material and build with bamboo more and more.”

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.