Materials “have so much more to give” says Bonnie Hvillum

Materials can become a much bigger part of our everyday lives and the way we see the world if people are willing to give up mass production, Natural Material Studio founder Bonnie Hvillum tells Dezeen in this interview.

Hvillum and her Copenhagen-based design and research studio have been pushing at the boundaries of what’s possible with different materials since 2018.

From charcoal-based garments to crockery made of surplus seafood shells, Natural Material Studio creates bespoke products using its own-developed biomaterials.

“Mass-produced materials are so homogenous”

“I prefer working from a ‘leftover’ kind of aspect,” explained Hvillum, whose ethos revolves around a circular approach.

“I want materials to play an active role in our way of understanding the world,” she told Dezeen. “I feel like we have become too familiar and comfortable.

“It’s become too convenient with mass production – mass-produced materials are so homogenous and so refined. Machinery textiles are just the same when they come out, there’s no variation,” the designer added.

“We’ve had an industrial process where materials have become quite neutral, in a way. I just feel like they have so much more to give and they can be part of shaping how we think, talk about and perceive the world.”

Natural Material Studio uses a combination of simple mechanical machinery – such as a process similar to “whipping cream” when creating its biodegradable B-foam – and more manual techniques.

For example, Procel is a home-compostable, protein-based bioplastic of natural softener and pigments developed by the studio that is made into sheets using hand casting.

“It’s the handcrafted aspects that make the materials so special,” said Hvillum, referencing the random and unique patterns that emerge on the surface of the materials produced by the studio.

Hvillum’s belief is that this approach to making things can highlight the inherent value in their materiality. Sustainable design, she said, should only be “a base point”.

“I’m more curious to talk about what these materials actually do,” she added.

“How they affect us, what they make us think and do and how they can be part of transforming the world instead of just [approaching design] with this linear thinking of replacing materials with existing ones – although of course that is also needed.”

“I needed that connection with the physical world”

Educated primarily as an interaction designer, Hvillum previously founded a consultancy called Social Design Lab.

The now-defunct company assisted professional organisations, including political parties, with “how they could think more holistically, or ‘circular’, as we call it today, in all aspects of resources including human and material resources,” according to the designer.

“I wasn’t critical of things. It was very much facilitating processes and advising and strategies and stuff. I needed that connection with the physical world,” reflected Hvillum, explaining her decision to launch Natural Material Studio.

Despite the shift, Hvillum stressed that human interaction is still at the core of her practice.

“I’m very curious about and absorbed in what we could almost call the cognitive aspects of these unconscious processes that we have in our brain. Like, why do we experience some materials in this way and others in that way?”

During the most recent edition of Milan design week, the studio showcased Brick Textiles – stretchy panels made from a combination of Procel and highly porous repurposed bricks that were classified as waste after demolition projects.

The project, which is defined by uncharacteristically “soft” bricks, proposes fresh ways of thinking about an existing resource, according to Hvillum.

Hvillum is optimistic that a change in the way consumers and designers think about materials is possible.

“It’s so inspiring speaking to young people because they really see the world differently,” she said.

“These changes that we’re seeing around social equality – fluidness in terms of genders, for example – all these things are also very inspiring when we talk about design and architecture and art, because it makes us start to understand that these fields can be fluid and equal, too.”

“I feel these movements that we’re seeing on the more cultural and societal and social levels could actually inform us in ways within design and architecture – but only if we are listening.”

The photography is courtesy of Natural Material Studio.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

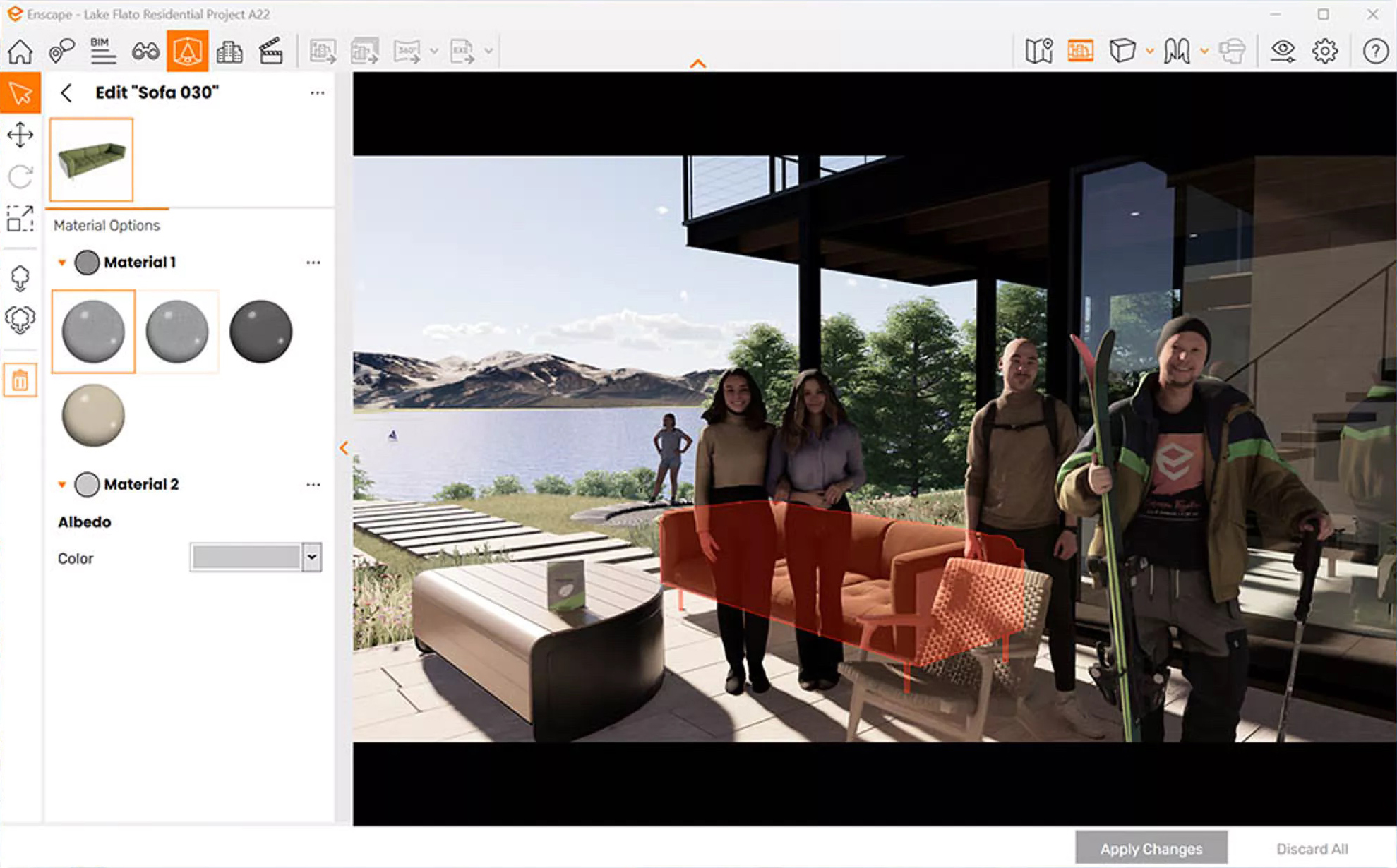

3. Customize your project materials.

3. Customize your project materials.

5. Fine-tune in post-production.

5. Fine-tune in post-production.

Designed to teach and encourage visitors to engage with contemporary issues, the Mercy Corps building was built to exemplify a sustainable, community-focused approach. Doubling the size of the historic Portland Packer-Scott Building, the landmark project combined a green roof, with resource-friendly landscaping and a glass and terracotta envelope.

Designed to teach and encourage visitors to engage with contemporary issues, the Mercy Corps building was built to exemplify a sustainable, community-focused approach. Doubling the size of the historic Portland Packer-Scott Building, the landmark project combined a green roof, with resource-friendly landscaping and a glass and terracotta envelope.

For the design of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Southwest Fisheries building, the team partnered with the University of California San Diego to design a facility that would pay homage to a world-class site and create a sustainable building for environmental stewards of the ocean.

For the design of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Southwest Fisheries building, the team partnered with the University of California San Diego to design a facility that would pay homage to a world-class site and create a sustainable building for environmental stewards of the ocean.

For this music center in Los Angeles ,the project includes a high-tech recording studio, spaces for rehearsal and teaching, a café and social space for students, and an Internet-based music production center. Music industry executive and philanthropist Morris “Mo” Ostin donated $10 million to UCLA for the music facility, now known as the Evelyn and Mo Ostin Music Center. Adjacent to the Schoenberg Music Building and the Inverted Fountain, the new structures provide faculty and students access to the latest advances in music technology, research and technology.

For this music center in Los Angeles ,the project includes a high-tech recording studio, spaces for rehearsal and teaching, a café and social space for students, and an Internet-based music production center. Music industry executive and philanthropist Morris “Mo” Ostin donated $10 million to UCLA for the music facility, now known as the Evelyn and Mo Ostin Music Center. Adjacent to the Schoenberg Music Building and the Inverted Fountain, the new structures provide faculty and students access to the latest advances in music technology, research and technology.

The Lunder Arts Center at Lesley was designed to be the new heart of the College of Art and Design. A center for art teaching and making, the campus is a crossroads for academic, artistic, and neighborhood communities. The terra-cotta and glass design foregrounds the site’s important historic church, initiating a dialog between 19th century religious and 21st century educational icons. An art gallery in the new glass building and a library in the historic church anchor the building at both ends; both are open to the public.

The Lunder Arts Center at Lesley was designed to be the new heart of the College of Art and Design. A center for art teaching and making, the campus is a crossroads for academic, artistic, and neighborhood communities. The terra-cotta and glass design foregrounds the site’s important historic church, initiating a dialog between 19th century religious and 21st century educational icons. An art gallery in the new glass building and a library in the historic church anchor the building at both ends; both are open to the public.

Key to the success of the design of the new Stephen M. Ross School building was relating the typical tiered classroom to group study spaces. To do so, the design team developed a model for early site planning studies to address the pedagogical needs of the school, which focused on assessing the capacity of existing buildings to accommodate new teaching spaces. Equally important was a sense of local identity, both for the building on the university campus and for distinct groups within the school.

Key to the success of the design of the new Stephen M. Ross School building was relating the typical tiered classroom to group study spaces. To do so, the design team developed a model for early site planning studies to address the pedagogical needs of the school, which focused on assessing the capacity of existing buildings to accommodate new teaching spaces. Equally important was a sense of local identity, both for the building on the university campus and for distinct groups within the school.

As the centerpiece of the Des Moines Western Gateway Park urban renewal project, this public library was sited between the center of the city and a newly designed public park. As well as library facilities, the building contains a flexible activity space, education facilities, children’s play areas, a conference wing and a cafeteria. In plan, it responds to the orthogonal nature of the city blocks to the east while stretching out into the park to the west. This plan is extruded vertically with a glass-metal skin, which gives the building its distinctive appearance.

As the centerpiece of the Des Moines Western Gateway Park urban renewal project, this public library was sited between the center of the city and a newly designed public park. As well as library facilities, the building contains a flexible activity space, education facilities, children’s play areas, a conference wing and a cafeteria. In plan, it responds to the orthogonal nature of the city blocks to the east while stretching out into the park to the west. This plan is extruded vertically with a glass-metal skin, which gives the building its distinctive appearance.

Harkening back to the beginning of insulated glazing itself, the Halley VI Antarctic Research Station was designed for polar research. As the world’s first re-locatable research facility, it was constructed by Galliford Try for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). The project aimed to demonstrate ground-breaking architecture characterized by a compelling concept, but also a structure that’s executed with careful attention to detail and coordination.

Harkening back to the beginning of insulated glazing itself, the Halley VI Antarctic Research Station was designed for polar research. As the world’s first re-locatable research facility, it was constructed by Galliford Try for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). The project aimed to demonstrate ground-breaking architecture characterized by a compelling concept, but also a structure that’s executed with careful attention to detail and coordination.

Extending an existing university gymnastic hall with a testing laboratory, the Damesal project was designed with a new building on top. The project offered an opportunity to explore an architectural concept where the geometry of the additional floor is designed with a simple box shape in glass. The architectural and functional variation happens as the glass façade responds to the program and functions within the building. The building’s envelope embodies design and performance as a collaboration between the architect and the supplier of the customized glass solution.

Extending an existing university gymnastic hall with a testing laboratory, the Damesal project was designed with a new building on top. The project offered an opportunity to explore an architectural concept where the geometry of the additional floor is designed with a simple box shape in glass. The architectural and functional variation happens as the glass façade responds to the program and functions within the building. The building’s envelope embodies design and performance as a collaboration between the architect and the supplier of the customized glass solution.

The Greenpoint Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Station was designed as a two-story facility that supports FDNY ambulance crews and vehicles. The project was made with a strong, distinctive form occupying a prominent site in the rapidly developing neighborhood. The station’s requirements led to a four-part division of the facility. Because the space for housing vehicles called for a higher ceiling height than the rest of station, one side is taller than the other. This change organizes the building’s functions.

The Greenpoint Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Station was designed as a two-story facility that supports FDNY ambulance crews and vehicles. The project was made with a strong, distinctive form occupying a prominent site in the rapidly developing neighborhood. The station’s requirements led to a four-part division of the facility. Because the space for housing vehicles called for a higher ceiling height than the rest of station, one side is taller than the other. This change organizes the building’s functions.

The Koch Center was designed to provide advanced integrative healthcare and complex outpatient services. Patient-centered and family-centered care is at the forefront of the building’s medical program, announced by a triple-height lobby that offers respite from the surrounding streets. Infusion and radiation oncology areas, as well as diagnostic imaging, typically found in basement areas, are located on upper floors. This gives patients and staff the benefit of natural light.

The Koch Center was designed to provide advanced integrative healthcare and complex outpatient services. Patient-centered and family-centered care is at the forefront of the building’s medical program, announced by a triple-height lobby that offers respite from the surrounding streets. Infusion and radiation oncology areas, as well as diagnostic imaging, typically found in basement areas, are located on upper floors. This gives patients and staff the benefit of natural light.

SHA designed the Cité de l’Océan et du Surf museum to raise awareness of oceanic issues and explore educational and scientific aspects of the surf and sea. Centered around leisure, science, and ecology, the project was made in collaboration with Solange Fabião. The design includes the museum, exhibition areas, and a plaza, within a larger master plan. The building form derives from the spatial concept “under the sky”/“under the sea”.

SHA designed the Cité de l’Océan et du Surf museum to raise awareness of oceanic issues and explore educational and scientific aspects of the surf and sea. Centered around leisure, science, and ecology, the project was made in collaboration with Solange Fabião. The design includes the museum, exhibition areas, and a plaza, within a larger master plan. The building form derives from the spatial concept “under the sky”/“under the sea”.

Zahner became known for advanced metal surfaces and systems with both functional and ornamental forms. With ImageWall, Zahner has created a system that offers design versatility to make immersive experiences. With its accessible design tools, affordability, and wide range of applications, the perforated metal panel system empowers designers and architects to bring their visions to life.

Zahner became known for advanced metal surfaces and systems with both functional and ornamental forms. With ImageWall, Zahner has created a system that offers design versatility to make immersive experiences. With its accessible design tools, affordability, and wide range of applications, the perforated metal panel system empowers designers and architects to bring their visions to life.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the ImageWall system is its accessibility to designers. Gone are the days of tedious back-and-forth communication. With this system, designers can now conceptualize and design directly within an

One of the most remarkable aspects of the ImageWall system is its accessibility to designers. Gone are the days of tedious back-and-forth communication. With this system, designers can now conceptualize and design directly within an  The ImageWall perforated metal panels not only look beautiful, but also allow for more streamlined detailing. Through the use of pre-engineered elements and easy-install systems, the cost and lead times are significantly reduced compared to traditional custom solutions. This makes affordability a key advantage offered by Zahner’s system.

The ImageWall perforated metal panels not only look beautiful, but also allow for more streamlined detailing. Through the use of pre-engineered elements and easy-install systems, the cost and lead times are significantly reduced compared to traditional custom solutions. This makes affordability a key advantage offered by Zahner’s system. From sleek and modern metals like stainless steel and aluminum to warm and inviting materials like pre-weathered weathering steel and copper, ImageWall provides architects and designers with a wide selection of options to suit their desired aesthetic.

From sleek and modern metals like stainless steel and aluminum to warm and inviting materials like pre-weathered weathering steel and copper, ImageWall provides architects and designers with a wide selection of options to suit their desired aesthetic. At its heart, Zahner’s system has wide-ranging applications across architectural typologies. From commercial buildings to hospitality spaces, retail environments to multi-unit residential common areas, ImageWall seamlessly integrates with other building systems, structures, and assemblies.

At its heart, Zahner’s system has wide-ranging applications across architectural typologies. From commercial buildings to hospitality spaces, retail environments to multi-unit residential common areas, ImageWall seamlessly integrates with other building systems, structures, and assemblies. ImageWall offers a myriad of creative possibilities, including lighting options, material choices, and graphic integration. Backlighting adds a whole new dimension to architectural design, bringing depth, texture, and visual interest to spaces.

ImageWall offers a myriad of creative possibilities, including lighting options, material choices, and graphic integration. Backlighting adds a whole new dimension to architectural design, bringing depth, texture, and visual interest to spaces. With a vast array of materials to choose from, architects can find the perfect match for their desired aesthetic, whether it be sleek and modern or warm and organic. The graphic options also enable the integration of custom patterns, logos, or artwork, allowing architects to create truly unique and memorable spaces that leave a lasting impression.

With a vast array of materials to choose from, architects can find the perfect match for their desired aesthetic, whether it be sleek and modern or warm and organic. The graphic options also enable the integration of custom patterns, logos, or artwork, allowing architects to create truly unique and memorable spaces that leave a lasting impression. To appreciate the capabilities of perforated metal panels, there are many noteworthy case studies. For example, the ImageWall system was employed only a short walk from Canada’s Parliament buildings in Ottawa, Ontario, where the team of B+H Architects and Morguard collaborated with Zahner to enhance the experience of entering their office complex at

To appreciate the capabilities of perforated metal panels, there are many noteworthy case studies. For example, the ImageWall system was employed only a short walk from Canada’s Parliament buildings in Ottawa, Ontario, where the team of B+H Architects and Morguard collaborated with Zahner to enhance the experience of entering their office complex at  Zahner also collaborated on the Legacy Pavilion for

Zahner also collaborated on the Legacy Pavilion for  These case studies demonstrate how Zahner’s perforated metal panel system can be utilized by architects to enhance their designs. Its adaptability, material options, and creative possibilities have allowed architects to push boundaries and transform their visions into new landmarks.

These case studies demonstrate how Zahner’s perforated metal panel system can be utilized by architects to enhance their designs. Its adaptability, material options, and creative possibilities have allowed architects to push boundaries and transform their visions into new landmarks. ImageWall represents the evolution of architectural solutions, bridging the gap between visionary concepts and practical implementation. Its accessibility to designers, affordability, wide range of applications, and design potential make it a versatile and valuable tool for architects and designers alike.

ImageWall represents the evolution of architectural solutions, bridging the gap between visionary concepts and practical implementation. Its accessibility to designers, affordability, wide range of applications, and design potential make it a versatile and valuable tool for architects and designers alike.