Rendering the Future: An Architecture of Matte Black Façades

The winners of this year’s A+Product Awards have been announced. Stay tuned for the year’s edition of the A+Product Awards ebook in the coming months.

We first experience architecture through a façade. Whether made with an overhang for shelter, lively colors, or clear sight lines inside, buildings with a thoughtfully designed façade invite exploration. Over time, architects have worked with builders and manufacturers to rethink cladding, glazing, and doors to shape the entry sequence and building styles. Today, this exploration continues with the design and detailing of matte façades. Through diverse material and finish choices, designers are reimagining the building envelope.

Matte façades have increased in popularity around the world and across project types. By reflecting less light, these buildings hold a strong presence and become focal points in rural and urban environments. Depending on the type of material and color, the matte finish can highlight the cladding, structure or façade system in place. These projects have a textural look and feel, inviting interaction and connection. In turn, they can also be used as a counterpoint to other colors, textures or finishes. The surfaces can contrast glazing or the interior design to delineate between the interior and exterior. Representing the integration of materials and finishes in different climates and contexts, each of the following projects explores what it means to create matte façades today.

Sauna R

Designed by Matteo Foresti, Värmdö, Sweden

Made of black granite (Negresco) and dark wood (Oak), this sauna was designed to be a camera obscura, a box drawn to shape views of the landscape. Located in the middle of Stockholm’s archipelago, a narrow pathway brings the visitors to the sauna: a black box embedded in the rocks. The matte finish can be seen both inside and as part of the structure’s façade. As the team outlines, inside is a monolithic stone bench that faces the water through a large sliding window. On the back, a thick wall contains all the services: a small kitchen hidden behind the sliding doors and a bathroom illuminated by a skylight. At night, the small sauna resembles a lighthouse, a warm and cozy space illuminated from the inside.

Made of black granite (Negresco) and dark wood (Oak), this sauna was designed to be a camera obscura, a box drawn to shape views of the landscape. Located in the middle of Stockholm’s archipelago, a narrow pathway brings the visitors to the sauna: a black box embedded in the rocks. The matte finish can be seen both inside and as part of the structure’s façade. As the team outlines, inside is a monolithic stone bench that faces the water through a large sliding window. On the back, a thick wall contains all the services: a small kitchen hidden behind the sliding doors and a bathroom illuminated by a skylight. At night, the small sauna resembles a lighthouse, a warm and cozy space illuminated from the inside.

Textilmacher

Designed by Tillicharchitektur, Munich, Germany

Tillicharchitektur designed this building to host production and office spaces for a textile finishing and vending firm. Its iconic feature is the folded façade, which reimagines the simple cube. The matte bright surface of the anthracite pigmented concrete responds to its environment. Depending on the season, time of day, weather, and lighting, the façade continuously changes its character. In contrast to the expressive façade, the interior design leaves more space for the production process and the products in the showroom. The team explains that the limitation on few, but high class materials, is the main factor driving the interior.

Tillicharchitektur designed this building to host production and office spaces for a textile finishing and vending firm. Its iconic feature is the folded façade, which reimagines the simple cube. The matte bright surface of the anthracite pigmented concrete responds to its environment. Depending on the season, time of day, weather, and lighting, the façade continuously changes its character. In contrast to the expressive façade, the interior design leaves more space for the production process and the products in the showroom. The team explains that the limitation on few, but high class materials, is the main factor driving the interior.

LOU – Einfamilienhaus

Designed by AllesWirdGut, Lower Austria, Austria

On the fringe of the Vienna Woods sits this compact single-family house LOU. Resting on a steeply sloping site, the designers wanted the first impression to be reinforced by the matte black skin of the building. Inside, the project offers a spacious and varied living environment on staggered half-story levels. As the team notes, at each level, the house opens differently to the outside world. The main residential levels are nestled against the slope, separated from the garden only by an all around-strip of windows which allows looking and stepping out in every direction.

On the fringe of the Vienna Woods sits this compact single-family house LOU. Resting on a steeply sloping site, the designers wanted the first impression to be reinforced by the matte black skin of the building. Inside, the project offers a spacious and varied living environment on staggered half-story levels. As the team notes, at each level, the house opens differently to the outside world. The main residential levels are nestled against the slope, separated from the garden only by an all around-strip of windows which allows looking and stepping out in every direction.

Four Seasons House

Designed by Joris Verhoeven Architecture, Tilburg, Netherlands

This compact wooden house was designed by architect Joris Verhoeven for himself. Located within the Drijflanen nature reserve in Tilburg, the matte building is designed to be a part of nature. With its rough black façade, it was made to fit within the context of surrounding tree trunks. The cottage house is prefabricated and constructed out of wooden cassettes filled with flax insulation. In turn, the interior of the cassettes is made of birch plywood. Other parts of the interior, such as the interior door, kitchen and stair railing, are finished in matte black, just like the exterior window frames. In this way the inside and outside of the house were made to relate to one another.

This compact wooden house was designed by architect Joris Verhoeven for himself. Located within the Drijflanen nature reserve in Tilburg, the matte building is designed to be a part of nature. With its rough black façade, it was made to fit within the context of surrounding tree trunks. The cottage house is prefabricated and constructed out of wooden cassettes filled with flax insulation. In turn, the interior of the cassettes is made of birch plywood. Other parts of the interior, such as the interior door, kitchen and stair railing, are finished in matte black, just like the exterior window frames. In this way the inside and outside of the house were made to relate to one another.

Muangthongthani Carcare

Designed by Archimontage Design Fields Sophisticated, Nonthaburi, Thailand

Located in Muang Thong Thani, this project is the expansion of a car care center. The building is located on a 3230-square feet (300-meter) plot of land, with a long and narrow plot that required an in-depth organization of the building. Since the space of the car care center was too limited, a new space was necessary for project extension. The building consists of four small containers and four large containers. The design team made the building exterior to be painted in matte black but the interior is white. The external envelope includes the west façade and the roof, which have metal sunshades to reflect sunlight and protect the building from the heat.

Located in Muang Thong Thani, this project is the expansion of a car care center. The building is located on a 3230-square feet (300-meter) plot of land, with a long and narrow plot that required an in-depth organization of the building. Since the space of the car care center was too limited, a new space was necessary for project extension. The building consists of four small containers and four large containers. The design team made the building exterior to be painted in matte black but the interior is white. The external envelope includes the west façade and the roof, which have metal sunshades to reflect sunlight and protect the building from the heat.

The Wetlands

Designed by Alain Carle Architect, Wentworth-Nord, Canada

The ‘Les Marais’ project started with the design team’s fascination for the built landscape of the empty space that characterizes North American rural areas. For this design, depending on the observer’s location in the neighboring forest, the scales of the buildings are relative. The team explains that the wetland nature of this lakeside property was preserved and then the collective landscape of the built complex was designed. A large ‘plate’ of black wood links the three structures to establish a common base, while large cutouts were made in each ‘shape’, also of black painted wood, to reveal the interior materiality of the red cedar buildings.

The ‘Les Marais’ project started with the design team’s fascination for the built landscape of the empty space that characterizes North American rural areas. For this design, depending on the observer’s location in the neighboring forest, the scales of the buildings are relative. The team explains that the wetland nature of this lakeside property was preserved and then the collective landscape of the built complex was designed. A large ‘plate’ of black wood links the three structures to establish a common base, while large cutouts were made in each ‘shape’, also of black painted wood, to reveal the interior materiality of the red cedar buildings.

JianYe LanHai ZhengFeng Hotel

Designed by Lacime Architect, Xinzheng, China

Sited at the future land-air transport hub of Henan, this hotel was made as a “paradise city with national customs” in Zhengzhou. Ideas of Chinese ancient garden construction were introduced into the “south garden” that make the most important building the starting point of the entire array. Moreover, the matte building façade is presented in the shape of arc to match the main garden in the front. The team choose a range of matte-finish materials like frosted earthenware tile, matte composite aluminum-plastic sheet and brushed stainless steel. It is the first floor of the building that is composed of external matte façade built from 100,000 earthenware tiles.

Sited at the future land-air transport hub of Henan, this hotel was made as a “paradise city with national customs” in Zhengzhou. Ideas of Chinese ancient garden construction were introduced into the “south garden” that make the most important building the starting point of the entire array. Moreover, the matte building façade is presented in the shape of arc to match the main garden in the front. The team choose a range of matte-finish materials like frosted earthenware tile, matte composite aluminum-plastic sheet and brushed stainless steel. It is the first floor of the building that is composed of external matte façade built from 100,000 earthenware tiles.

The winners of this year’s A+Product Awards have been announced. Stay tuned for the year’s edition of the A+Product Awards ebook in the coming months.

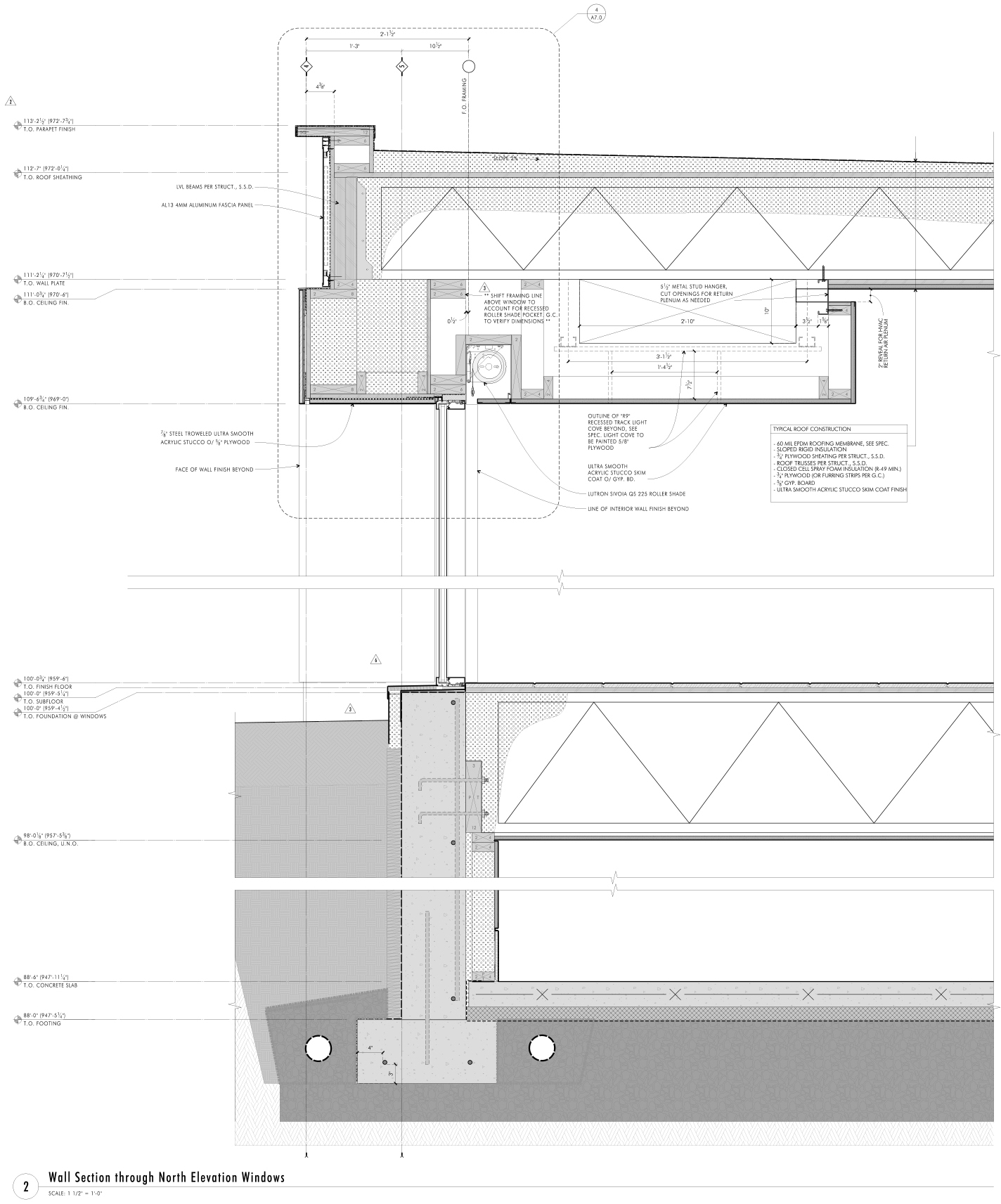

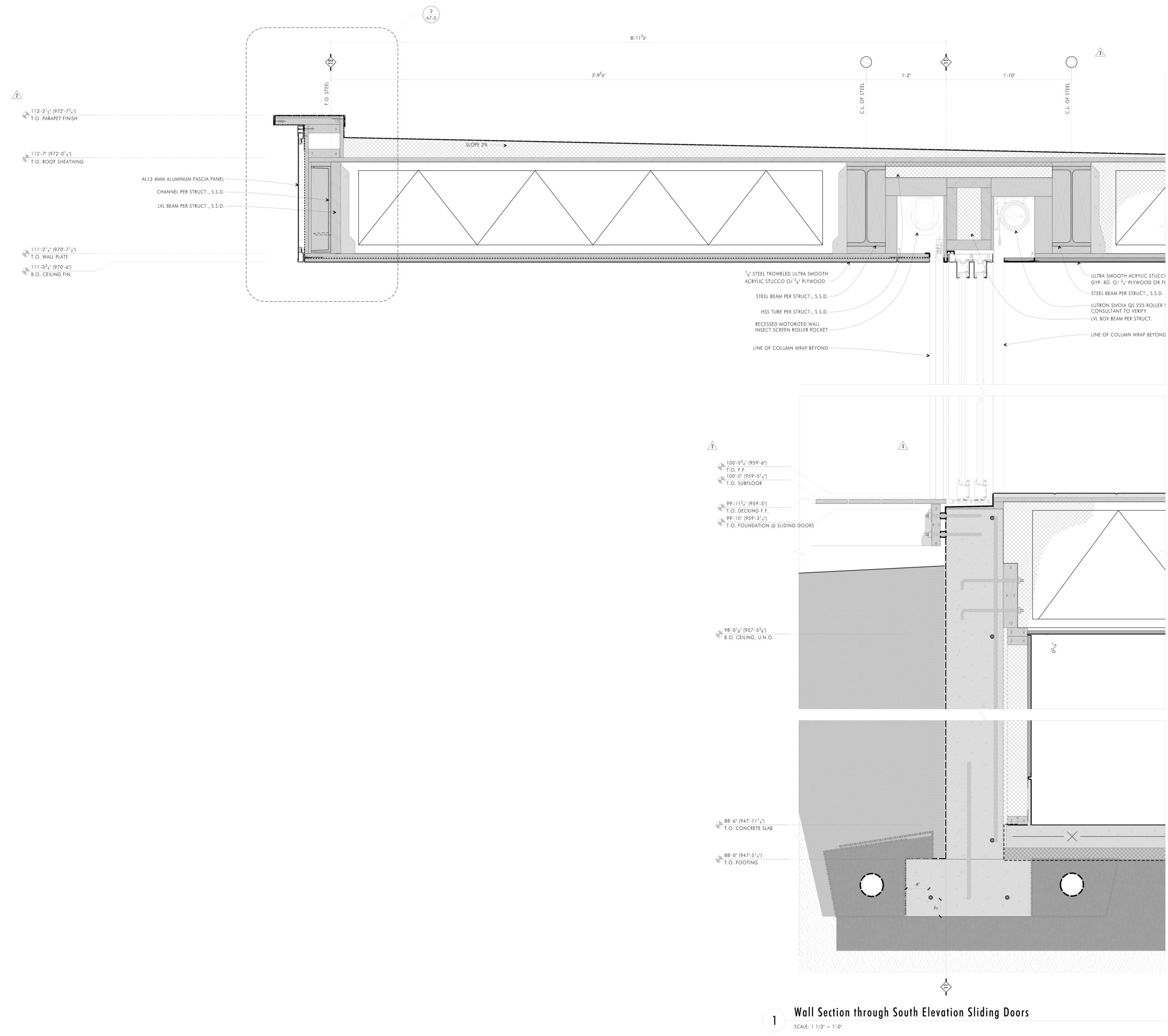

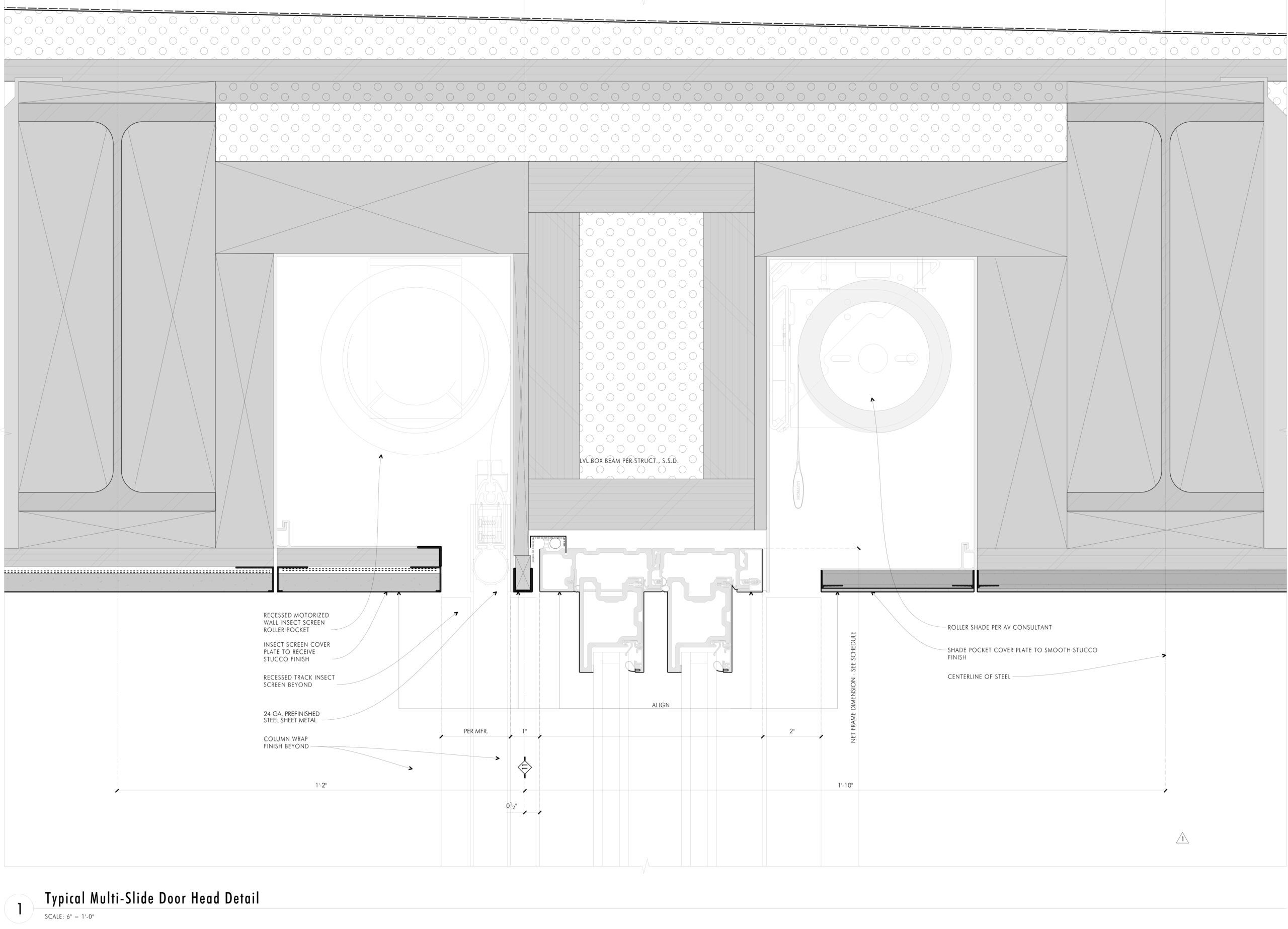

Making a Glass House Structurally Sound

Making a Glass House Structurally Sound

The most staggering feats of engineering are the two 60-foot-long glass walls, which line opposing aspects of the residence. Each wall is made up of three sets of 20-foot sliding doors with only 4 inches of steel structure in between them, allowing for uncompromised views throughout. Like the other Marvin Modern products, the profile of each door is slim and inconspicuous. Recessed channels in the frames conceal motorized insect screens and blackout shades, while still providing consistent, narrow sightlines of less than three inches.

The most staggering feats of engineering are the two 60-foot-long glass walls, which line opposing aspects of the residence. Each wall is made up of three sets of 20-foot sliding doors with only 4 inches of steel structure in between them, allowing for uncompromised views throughout. Like the other Marvin Modern products, the profile of each door is slim and inconspicuous. Recessed channels in the frames conceal motorized insect screens and blackout shades, while still providing consistent, narrow sightlines of less than three inches. The swaths of glass are a portal to the organic terrain, rather than an obstruction. To that end, internal covers across the frames disguise fasteners and rubber gaskets, while low-gloss aluminum interior finishes and black spacer bars ensure an unimpeded outlook. This seamless finish allows inner and outer worlds to collide. In the warmer months when the doors are retracted, the covered deck becomes a natural extension of the interior floor plan.

The swaths of glass are a portal to the organic terrain, rather than an obstruction. To that end, internal covers across the frames disguise fasteners and rubber gaskets, while low-gloss aluminum interior finishes and black spacer bars ensure an unimpeded outlook. This seamless finish allows inner and outer worlds to collide. In the warmer months when the doors are retracted, the covered deck becomes a natural extension of the interior floor plan.