“Emerging Ecologies” at MoMA Celebrates the Utopian Side of Environmental Design

Architizer’s 12th Annual A+Awards are officially underway! Sign up for key program updates and prepare your submission ahead of the Main Entry Deadline on December 15th.

In 2023, terms like environmentalism and sustainability have a decidedly bleak emotional valence. Although the worst consequences of climate change are expected to arrive in future decades, the looming specter of this slow leviathan is having an emotional impact on people today. According to the Yale Program on Climate Communication, 3% of Americans regularly experience anxiety about climate change. The number is higher if you look at individual demographics. For instance, 5% of Americans under 35 suffer from climate anxiety, as do a shocking 10% of Hispanic Americans.

Fear. Depression. These are the emotions that the phrase climate change evokes. Morally, the term coincides with a demand for austerity, an idea of living with less. It is no surprise, then, that many climate activists, like countless religious movements of old, have a decidedly iconoclastic rhetorical bent. The notorious Just Stop Oil organization made headlines by throwing soup on famous paintings like Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. Like Girolamo Savonarola, who burned Renaissance masterpieces to protest sexual immorality, Just Stop Oil carries a grim and uncompromising sermon. They desecrate art, they say, to mirror the way industrial society desecrates nature.

Girolamo Savonarola leading a “Bonfire of the Vanities” in 15th century Florence, encouraging his followers to burn “immoral” painitngs. Painting by Ludwig von Langenmantel, 1879, via Wikimedia Commons.

But here is the problem with puritanical movements: they fizzle out. Some people are motivated by a call for austerity, but most are not. People want joy. They want beauty. They want to be told that there is a way for them to live well, today, in this life. They do not want to forsake the present for the world to come. Well intentioned or not, if the vision of a sustainable future is a vision of deprivation, it will not motivate people to change their behavior.

This has been my perspective for a while now. And it is why I enjoyed “Emerging Ecologies”, MoMA’s new exhibition on environmental design. Unlike another exhibition I recently visited on sustainability — “The Future is Present“ at the Design Museum in Denmark — “Emerging Ecologies” is not a dystopian lecture about the way our progeny will need to learn with less. To the contrary, the exhibition celebrates architects of the past who grappled with the question of how to design with the environment, taking their cues from the landscape. The show reveals how this approach is not only ethical, but has the potential to produce buildings that are beautiful, quirky, creative and stimulating. Drab this show is not.

“Emerging Ecologies” showcases a few contemporary projects, but the emphasis is on work from the 1960s and 70s, the period when the idea of ecology was still “emerging.” The first thing visitors to the exhibition see is a magnificent model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, perhaps the only 20th century building that both modernists and traditionalists agree to be a masterpiece.

The centrality of Fallingwater is, I think, the most inspired curatorial choice in the exhibition. But what does it have to do with sustainability? Quite a bit, it seems. Frank Lloyd Wright’s building is designed to complement the landscape rather than dominate it. While the building might not have been created with the purpose of lowering carbon emissions, it does represent the type of attitude architects might come to embrace if they are serious about the ideal of sustainability. Working with nature, rather than against it, could lead us to a future where people live and work in buildings like Fallingwater — an attractive prospect indeed.

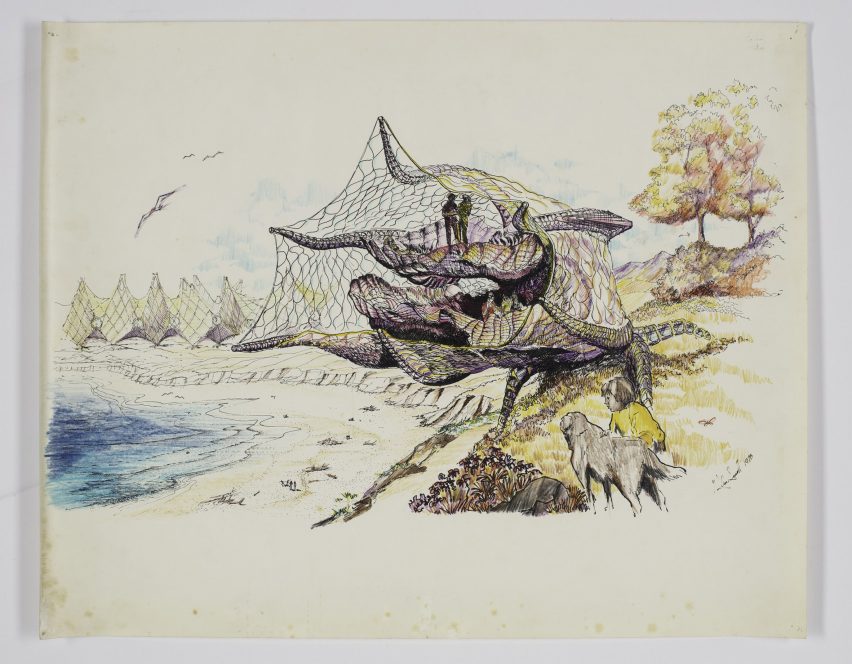

Other projects featured early on in the show include Malcom Wells’s design for subterranean suburban dwellings, an approach playfully known today as “hobbitecture.” Wells was interested in these types of dwellings in the early 1960s, but they really caught on in the 1970s, when the oil crisis led individuals to consider ways to reduce their consumption of fossil fuels. Wells’s view was a bit more ambitious than this. He hoped that subterranean architecture would allow “wilderness” to reclaim the American suburbs, quipping that it has the advantage of “millions of years of trial and error” over human civilization. On the surface, this quote seems to echo the misanthropy of Just Stop Oil, but the designs themselves belie this reading. Wells’s houses are cozy habitats for human flourishing.

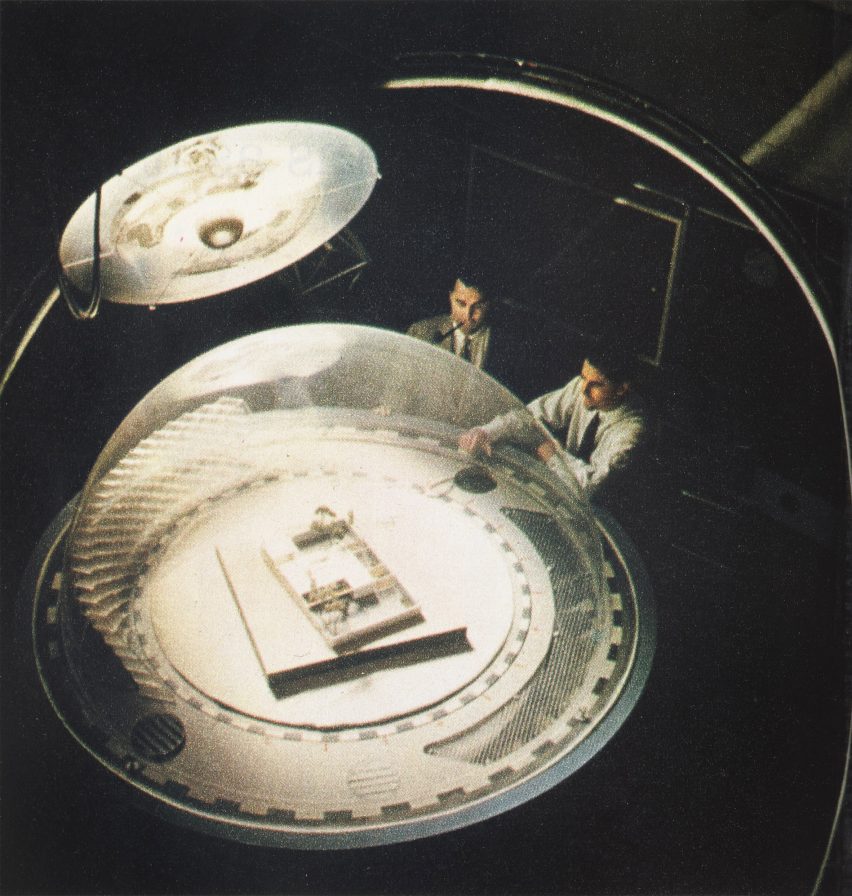

“Emerging Ecologies” is the inaugural presentation by the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment. Many of Ambasz’s works are among the 150 projects on display, and the curation, handled masterfully by Carson Chan, speaks to Ambasz’s commitment to an imaginative, even utopian vision of sustainable architecture. As Matt Shaw notes in his review for e-flux, the show “traces the twentieth century of American idealism, from crank scientists like Buckminster Fuller to later hippie fever dreams, such as Anna and Lawrence Halprin’s sixties-era nude summer workshops, in a surrealist collection of alternative US futures.” Within the exhibition, low-tech back to nature fantasies exist alongside futuristic visions such as that of the Cambridge Seven Associates, who proposed a lush and self-sustaining rainforest enclosed in a geodesic dome for the Tsuruhama Rainforest Pavilion in 1995.

“Emerging Ecologies” is refreshing in its lack of pedantry. It does not propose to know the way forward. Rather, it looks back to a history of environmental architecture in order to highlight a number of potential pathways. If you are in New York this holiday season, I strongly recommend skipping the Rockettes and seeing this instead. The exhibition runs until 20 January.

Cover Image: Vincent Van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Architizer’s 12th Annual A+Awards are officially underway! Sign up for key program updates and prepare your submission ahead of the Main Entry Deadline on December 15th.