Design Museum exhibition explores “surrealism and why it matters now”

Curator Kathryn Johnson explains the story behind surrealism and its impact on design in this video Dezeen produced for the Design Museum about its latest exhibition.

Titled Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today, the exhibition features almost 350 surrealist objects spanning fashion, furniture and film.

The exhibition, which was curated by Johnson, explores the conception of the surrealist movement in the 1920s and the impact it has had on the design world ever since.

It features some of the most recognised surrealist paintings and sculptures, including pieces by Salvador Dalí, Man Ray and Leonora Carrington, as well as work from contemporary artists and designers such as Dior and Björk.

“Surrealism was born out of the horrors of the first world war, in a period of conflict and uncertainty, and it was a creative response to that chaos,” Johnson said in the video.

“It saw in the fracturing of the world an opportunity to shake things up, to do things differently, to think differently, and to acknowledge the subconscious and its importance for our everyday lives.”

The exhibition explores surrealism’s impact on contemporary design, with nearly a third of the objects on show dating from the past 50 years.

“We want to start a conversation about what surrealism is and why it matters now,” Johnson said.

The name of the exhibition references the importance of the concept of desire within the movement. In the video, Johnson explained that the surrealist movement began with poetry, with French poet and author André Breton penning the first surrealist manifesto.

Breton described desire as “being the sole motivating force in the world” and “the only master humans should recognise.”

The exhibition is segmented into four themes. It begins with an introduction to surrealism from the 1920s and explores the influence of the movement on everyday objects, as well as its pivotal role in the evolution of design throughout the twentieth century.

Another part of the exhibition explores surrealism and interior design, since early protagonists of the movement were interested in capturing the aura or mystery of everyday household objects.

Objects on display include Marcel Duchamp’s Porte-Bouteilles, a sculpture made from bottle racks, and Man Ray’s Cadeau/Audace, a traditional flat iron with a single row of 14 nails.

The exhibition moves along to the 1940s, where designers started using surrealist art for ideas to create surprising and humorous objects. Items borne from this include Sella by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni and Jasper Morrison’s Handlebar Table.

A key section of the exhibition includes a spotlight on surrealism’s significance in the UK, documenting the partnership between Salvador Dalí and the British poet and art patron Edward James, whose collaboration resulted in some of the most notable works of surrealism such as the Mae West Lips sofas and the Lobster Telephone.

Another section of the exhibition examines surrealism and the body in relation to the human form, sexuality and desire.

Included in this section are Sarah Lucas’ Cigarette Tits, in which the language of tabloids is used to expose stereotypes of female sexuality, and Najla el Zein’s Hay, which highlights the sensory pleasures provided by everyday materials.

Photographs, vintage magazine covers and fashion items are on display to show the impact of surrealism on the fashion industry starting from the 1930s.

According to Johnson, “surrealism attracted more women than any other movement since romanticism.” As a result, she wanted to ensure there was a wide representation of female artists and designers in the exhibition.

“I think that was partly because of concerns about the body, about sexuality, and how the domestic were key themes of surrealism from the beginning,” she said.

“But those themes were approached in a very original and critical way by the women associated with the movement – some of whom would not have considered themselves surrealists but were in dialogue with those ideas.”

The final section of the exhibition looks at the surrealist preoccupation with challenging the creative process itself and how this resulted in original works of art and design.

According to Johnson, contemporary designers are still using ideas from early surrealism, such as welcoming chance into the creative process, or using techniques like automatism.

“The surrealists try to write and draw without thinking, and we see in the exhibitions and studies where they are drawing in an automatic way. But now, of course, contemporary designers have other tools to use to try and bypass the known and the conventional,” Johnson said.

An example of this in the exhibition is Sketch Chair by design studio Front, which was produced using motion capture technology to translate the movement of drawing in mid-air into a 3D-printed form.

“The surrealists knew that changing the mind would change the material world and we’re now at this frightening but thrilling juncture where we’re creating a computerised intelligence that can be creative,” Johnson said.

Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today opened at the Design Museum on 14 October 2022 and is on show until 19 February 2o23.

Tickets are available at designmuseum.org/surrealism.

Partnership content

This video was produced by Dezeen for Design Museum as part of a partnership. Find out more about Dezeen’s partnership content here.

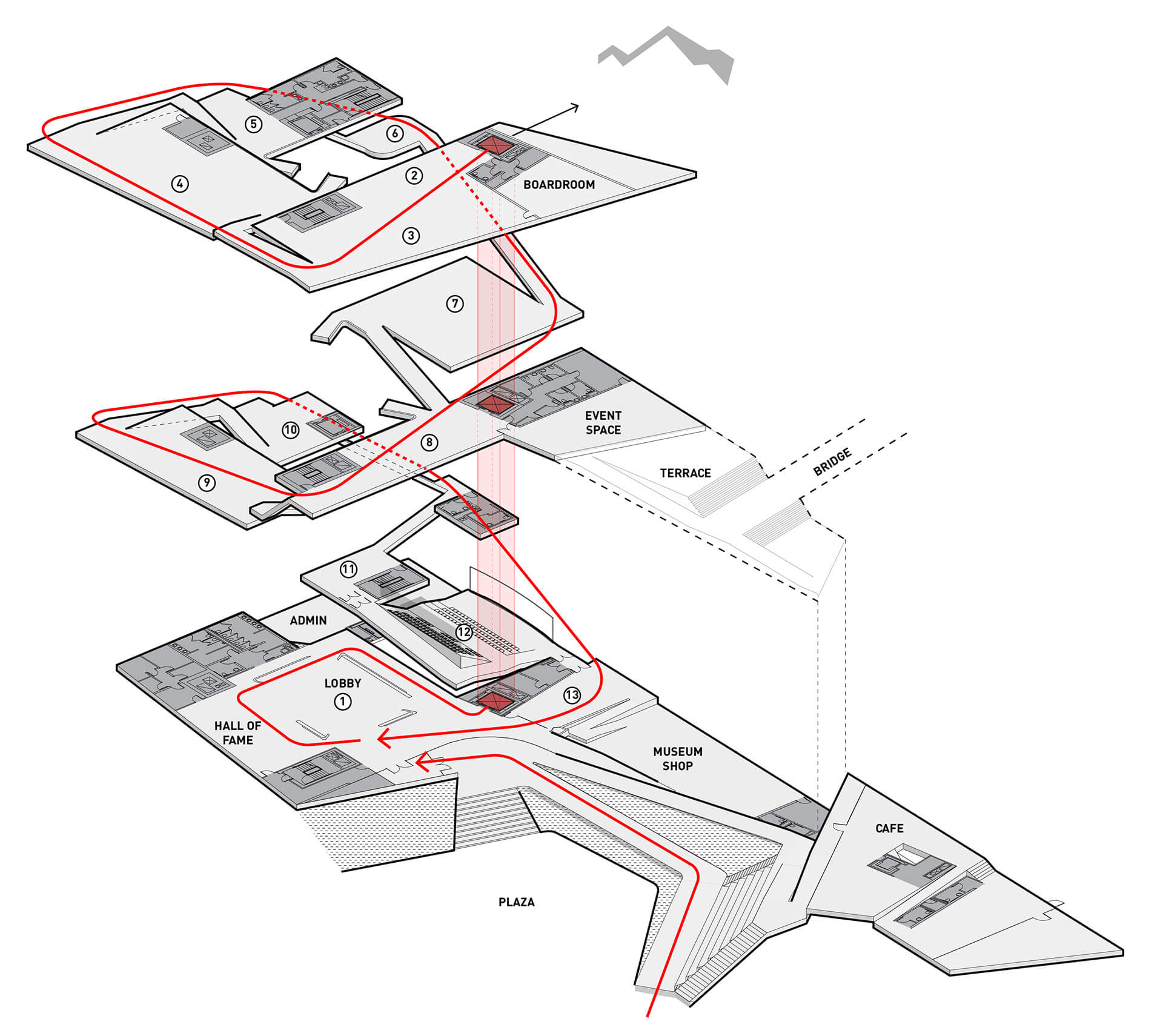

Ten years in the making, the United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum (USOPM) opened in 2020 as the first building of its kind to pay tribute to Olympic and Paralympic movements. The 60,000 square foot design features galleries, a state-of-the-art theater, event space and café, and was inspired by the energy and grace of Team USA athletes and the organization’s inclusive values.

Ten years in the making, the United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum (USOPM) opened in 2020 as the first building of its kind to pay tribute to Olympic and Paralympic movements. The 60,000 square foot design features galleries, a state-of-the-art theater, event space and café, and was inspired by the energy and grace of Team USA athletes and the organization’s inclusive values.

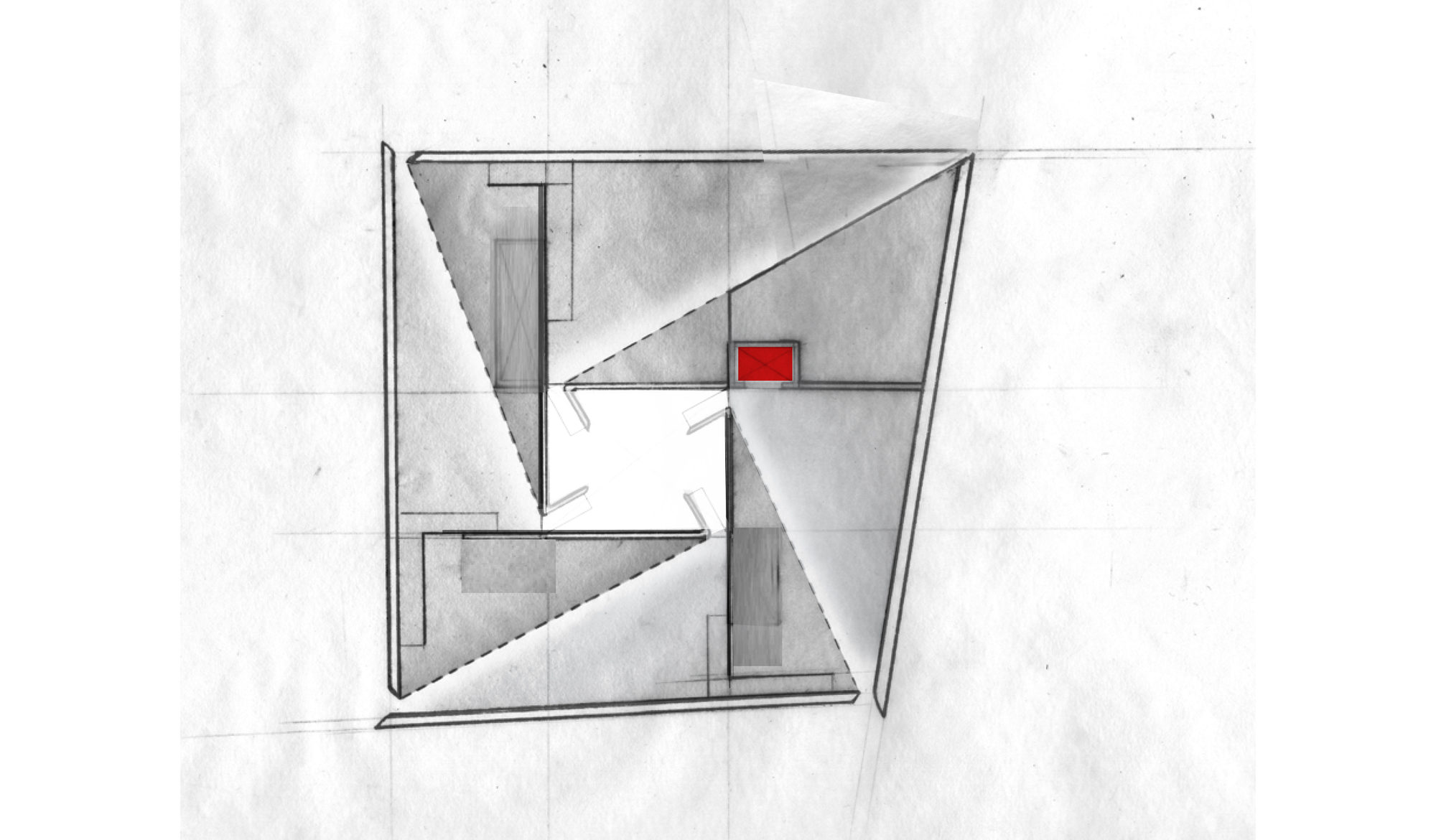

From the earliest stages of design, the team consulted Team USA athletes, including Paralympic athletes and persons with disabilities, to ensure the most authentic and inclusive experience. Ramps guide visitors down a gentle-grade downhill circulation path that enables easier movement. These ramps have been widened to 6 feet to accommodate the side-by-side movement of two visitors including a wheelchair.

From the earliest stages of design, the team consulted Team USA athletes, including Paralympic athletes and persons with disabilities, to ensure the most authentic and inclusive experience. Ramps guide visitors down a gentle-grade downhill circulation path that enables easier movement. These ramps have been widened to 6 feet to accommodate the side-by-side movement of two visitors including a wheelchair.

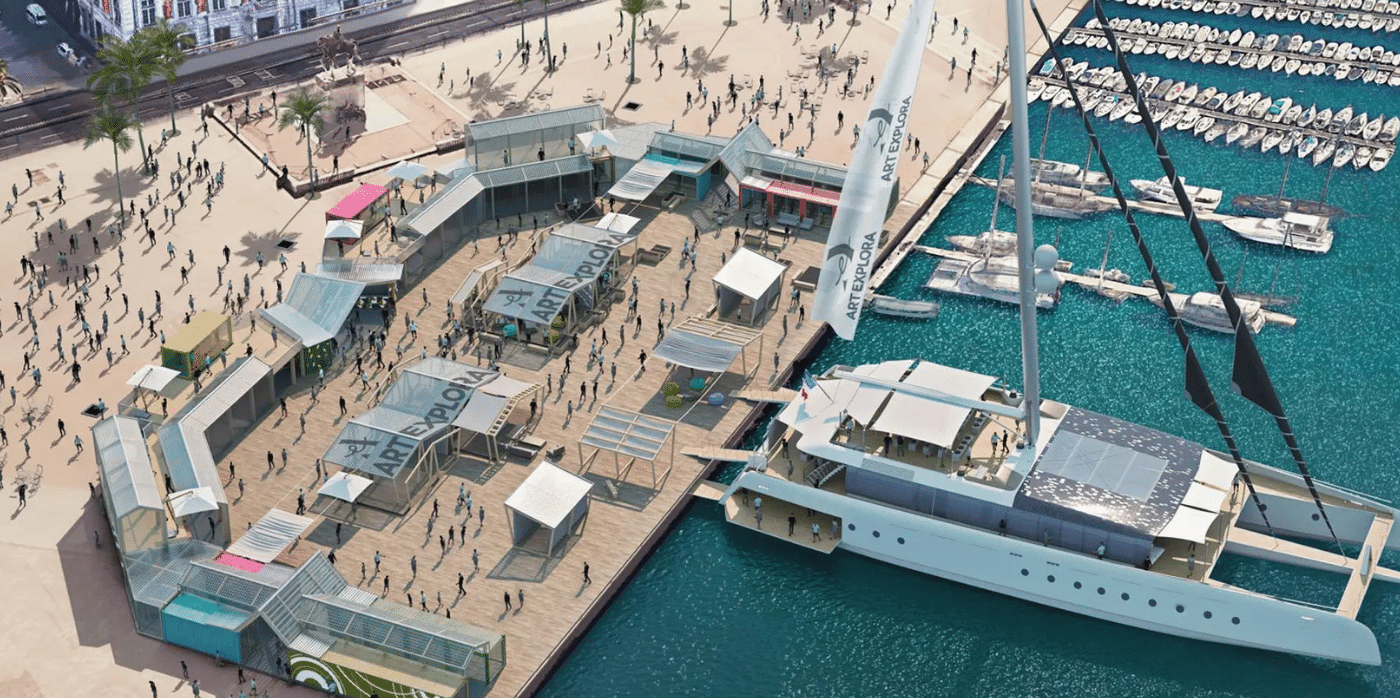

Outside, a terraced hardscape plaza is at the heart of the museum complex, with the museum building to the south and the café to the north. In addition, the Park Union Bridge is a 250-foot curved steel structure that floats above an active railyard. Two interlocked loops, stretching from either side of the railyard, connect the museum and America the Beautiful Park.

Outside, a terraced hardscape plaza is at the heart of the museum complex, with the museum building to the south and the café to the north. In addition, the Park Union Bridge is a 250-foot curved steel structure that floats above an active railyard. Two interlocked loops, stretching from either side of the railyard, connect the museum and America the Beautiful Park.

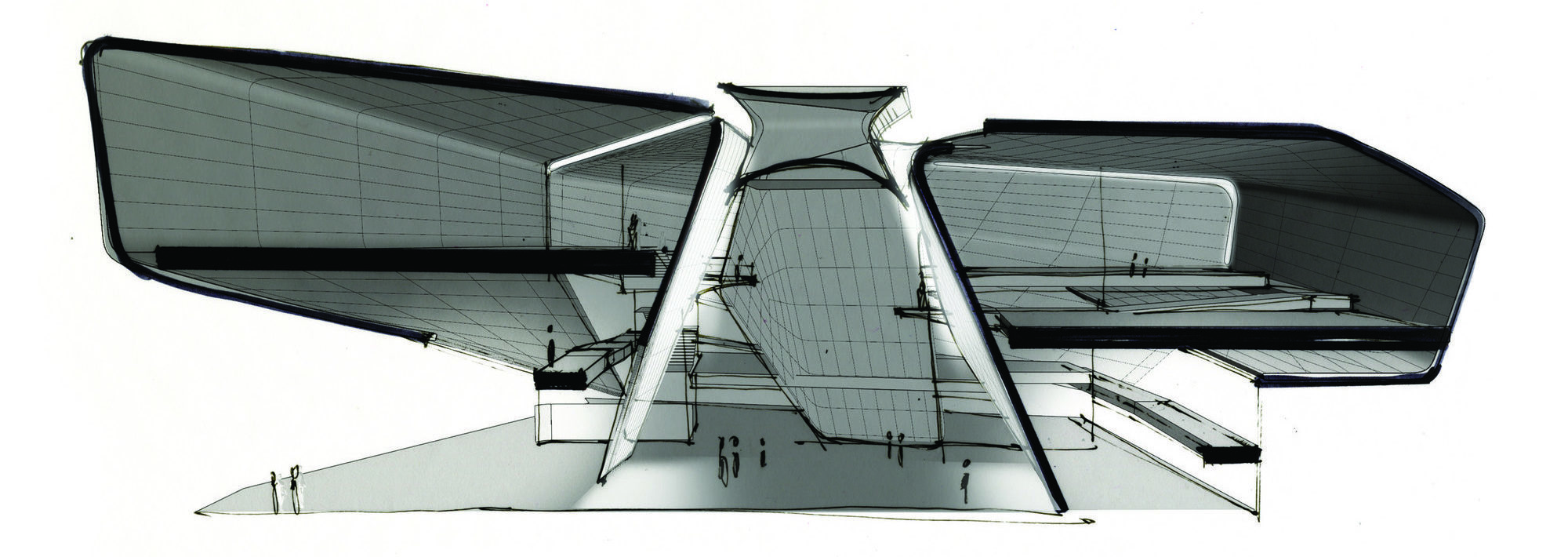

Diller Scofidio + Renfro worked with Lorin Industries on the aluminum panels, as well as MG McGrath and Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope on the curtain walls. Bringing the vision of the building’s exterior to life, the teams wanted to create a building structure and overall exterior visual effect that encapsulated the passion, dedication, and endurance of an Olympic athlete. To achieve this, a system of custom metal panels with integrated gutters wrap the double-curved geometry of the façade.

Diller Scofidio + Renfro worked with Lorin Industries on the aluminum panels, as well as MG McGrath and Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope on the curtain walls. Bringing the vision of the building’s exterior to life, the teams wanted to create a building structure and overall exterior visual effect that encapsulated the passion, dedication, and endurance of an Olympic athlete. To achieve this, a system of custom metal panels with integrated gutters wrap the double-curved geometry of the façade.

Lorin pioneered the coil anodizing process, which protects the aluminum while also improving its aesthetic properties and durability. The panels are 100% recyclable helping to meet the project’s LEED requirements. Lorin’s anodized stainless finish is created by an electro-chemical process that builds an anodic layer from the aluminum, molecularly bonding it to the surface. It protects aluminum from oxidation, scratching, and other hazards far better than natural oxidizing, and it requires minimal upkeep while resisting scratches and finger prints. Even with its light weight, coil anodized aluminum has an exterior surface hardness second only to diamond and is therefore unmatched in abrasion resistance and durability.

Lorin pioneered the coil anodizing process, which protects the aluminum while also improving its aesthetic properties and durability. The panels are 100% recyclable helping to meet the project’s LEED requirements. Lorin’s anodized stainless finish is created by an electro-chemical process that builds an anodic layer from the aluminum, molecularly bonding it to the surface. It protects aluminum from oxidation, scratching, and other hazards far better than natural oxidizing, and it requires minimal upkeep while resisting scratches and finger prints. Even with its light weight, coil anodized aluminum has an exterior surface hardness second only to diamond and is therefore unmatched in abrasion resistance and durability.

Putting Team USA athletes at the center of the museum experience, the design team created a museum that’s as functional and accessible as it is beautiful. The design rises with the primary structural systems consisting of a steel frame superstructure, drilled shaft caisson foundations, and cast-in-place concrete lateral cores. From this, the exterior shell further accentuates the dynamism of the building concept and purpose, with each metallic panel animated by the extraordinary light quality in Colorado Springs, producing gradients of color and shade that give the building another sense of motion. If great architecture reflects a common purpose and creates rich experiences, this is certainly the case in DS+R’s United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum.

Putting Team USA athletes at the center of the museum experience, the design team created a museum that’s as functional and accessible as it is beautiful. The design rises with the primary structural systems consisting of a steel frame superstructure, drilled shaft caisson foundations, and cast-in-place concrete lateral cores. From this, the exterior shell further accentuates the dynamism of the building concept and purpose, with each metallic panel animated by the extraordinary light quality in Colorado Springs, producing gradients of color and shade that give the building another sense of motion. If great architecture reflects a common purpose and creates rich experiences, this is certainly the case in DS+R’s United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum.