Sungai Watch chair consists of 2,000 plastic bags from Bali’s rivers

Indonesian non-profit Sungai Watch has unveiled the debut furniture launch from its design studio Sungai Design, aimed at creating useful products from the mountains of plastic waste that it fishes from Bali’s rivers every day.

The Ombak lounge chair, created in collaboration with American designer Mike Russek, is made using a sheet material produced entirely from discarded plastic bags, with around 2,000 needed for every chair.

The bags are collected by Sungai Watch, which is on a mission to eliminate ocean plastic pollution using its own system of floating barriers to capture the waste as it flows along Indonesia’s rivers.

Since its inception three years ago, the organisation has installed 270 barriers and collected more than 1.8 million kilograms of plastic, resulting in a huge stockpile of material.

Plastic bags are the most frequently collected item and also the least sought after in terms of future value, which led the team to focus on creating a product collection using this readily available resource.

“Collecting and amassing plastic waste solves one part of the problem of plastic pollution, the second challenge is what to actually do with all of this plastic,” said Kelly Bencheghib, who co-founded Sungai Watch with her brothers Sam and Gary.

“As we collected hundreds of thousands of kilograms of plastics, we started to look at plastic as an excellent source material for everyday products we all need and use, from furniture to small goods to even art,” she added.

Sungai Design has created two variations of the Ombak lounge chair – with and without armrests – manufactured in Bali using processes that aim to minimise waste during production.

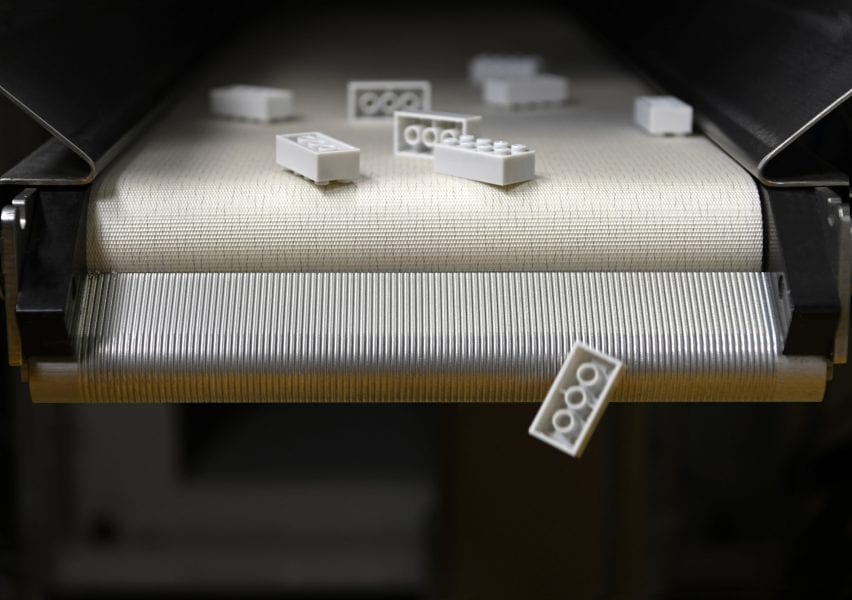

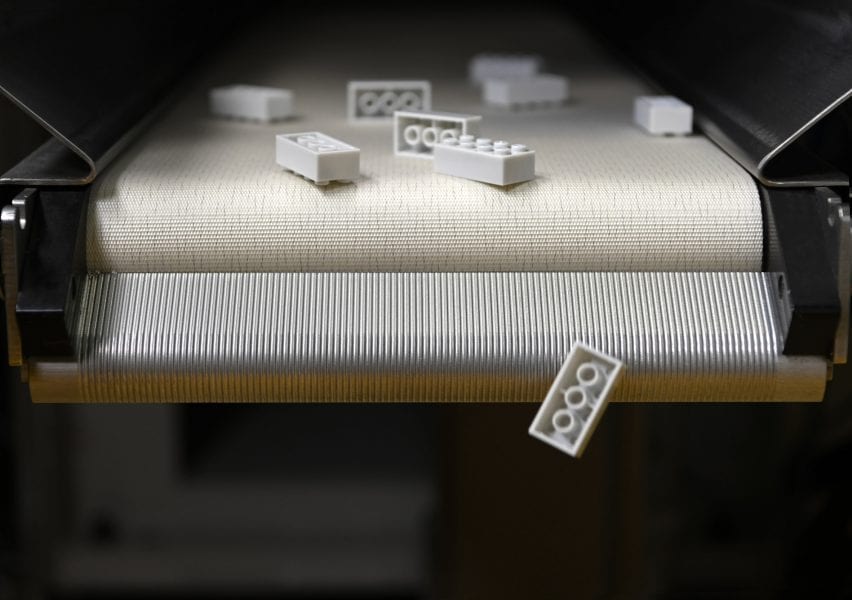

The plastic bags are thoroughly washed to remove any impurities before being shredded and heat-pressed to form hard, durable sheets.

Precision CNC cutting machinery is used to carve out the different components, which are carefully shaped to minimise material use and leave no offcuts.

The panels are connected by a concealed metal structure, resulting in a pure and visually lightweight form with a simple slatted construction.

Although the design is available in three distinct colourways – Granite Black, Ocean Blue and Concrete White – the upcycling process produces slight variations in the tone and texture of the material, meaning each chair has a unique quality.

Ombak means wave in Indonesian and the name references Sungai Design’s commitment to cleaning up rivers and oceans.

In line with this aim, Sundai Design has pledged to minimise its carbon footprint and put in place processes to audit and track the sources of the plastic used in its products.

The company is planning to release other products using the same material and, as a social enterprises, will donate part of its revenue to Sungai Watch to further the project as it seeks to clean up rivers in Indonesia and beyond.

“There is so much potential with this material,” added Sam Bencheghib. “When you choose a chair from our collection, you’re not just selecting a piece of furniture; you’re embracing the transformation from waste to a beautiful, functional piece of art that has found its place in your home.”

Every year, Indonesia accounts for 1.3 million of the eight million tonnes of plastic that end up in our oceans, making it one of the world’s worst marine polluters.

Other attempts at collecting this waste and finding new uses for it have come from design studio Space Available, which set up a circular design museum with a recycling station and facade made of 200,000 plastic bottles in Bali in 2022.

The studio also teamed up with DJ Peggy Gou turn rubbish collected from streets and waterways in Indonesia into a chair with an integrated vinyl shelf.

“The trash is just everywhere, in the streets and rivers,” Space Available founder Daniel Mitchell told Dezeen.

“It’s not the fault of the people, there’s just very little structural support, waste collection or education,” he added. “Households are left to dispose of their own waste and most ends up in rivers or being burned.”