Tropical Modernism exhibition explores “the politics behind the concrete”

London’s Victoria and Albert Museum has launched its Tropical Modernism exhibition, which highlights the architectural movement’s evolution from colonial import to a “tool of nation building”.

According to the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), the exhibition aims to examine the complex context, power dynamics and post-colonial legacy of tropical modernism – an architectural style that developed in South Asia and West Africa in the late 1940s – while also centralising and celebrating its hidden figures.

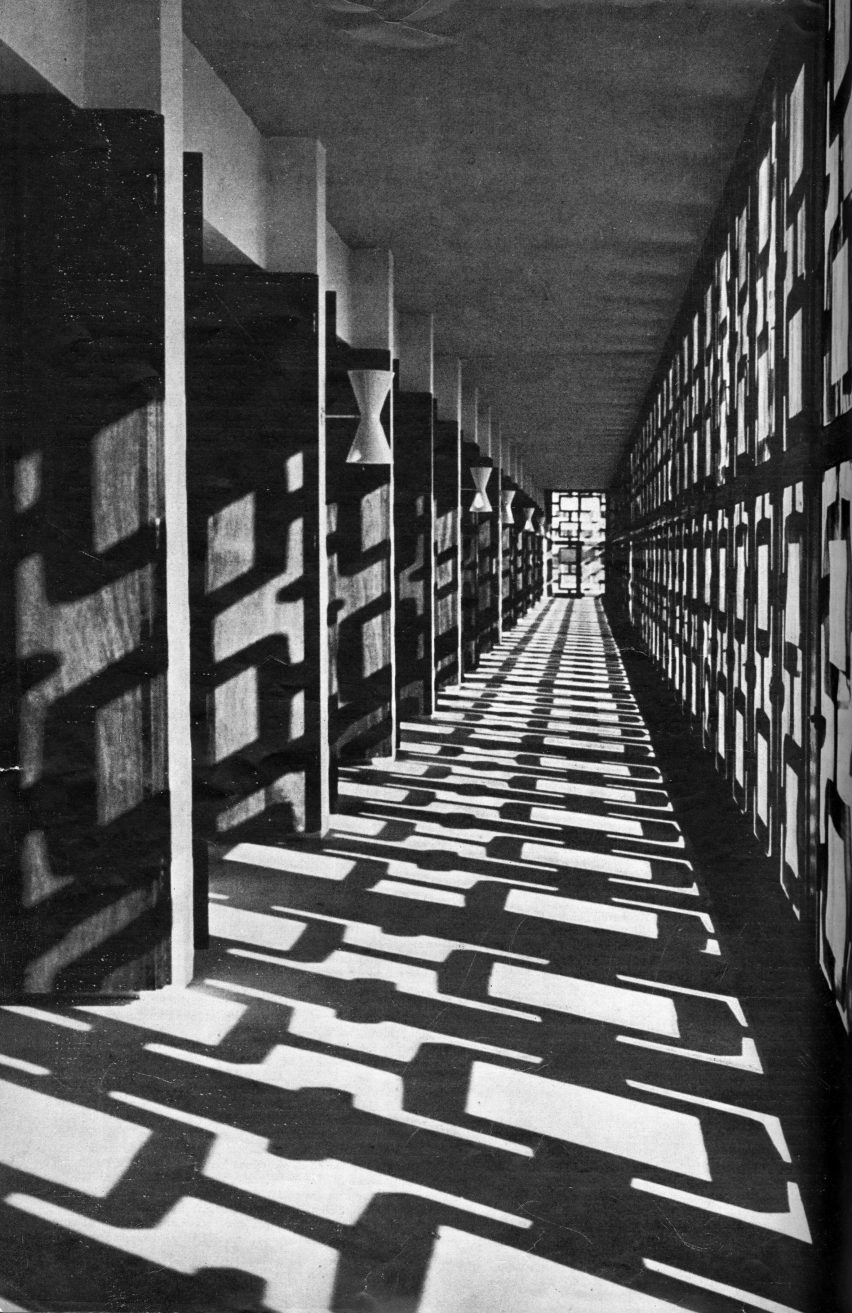

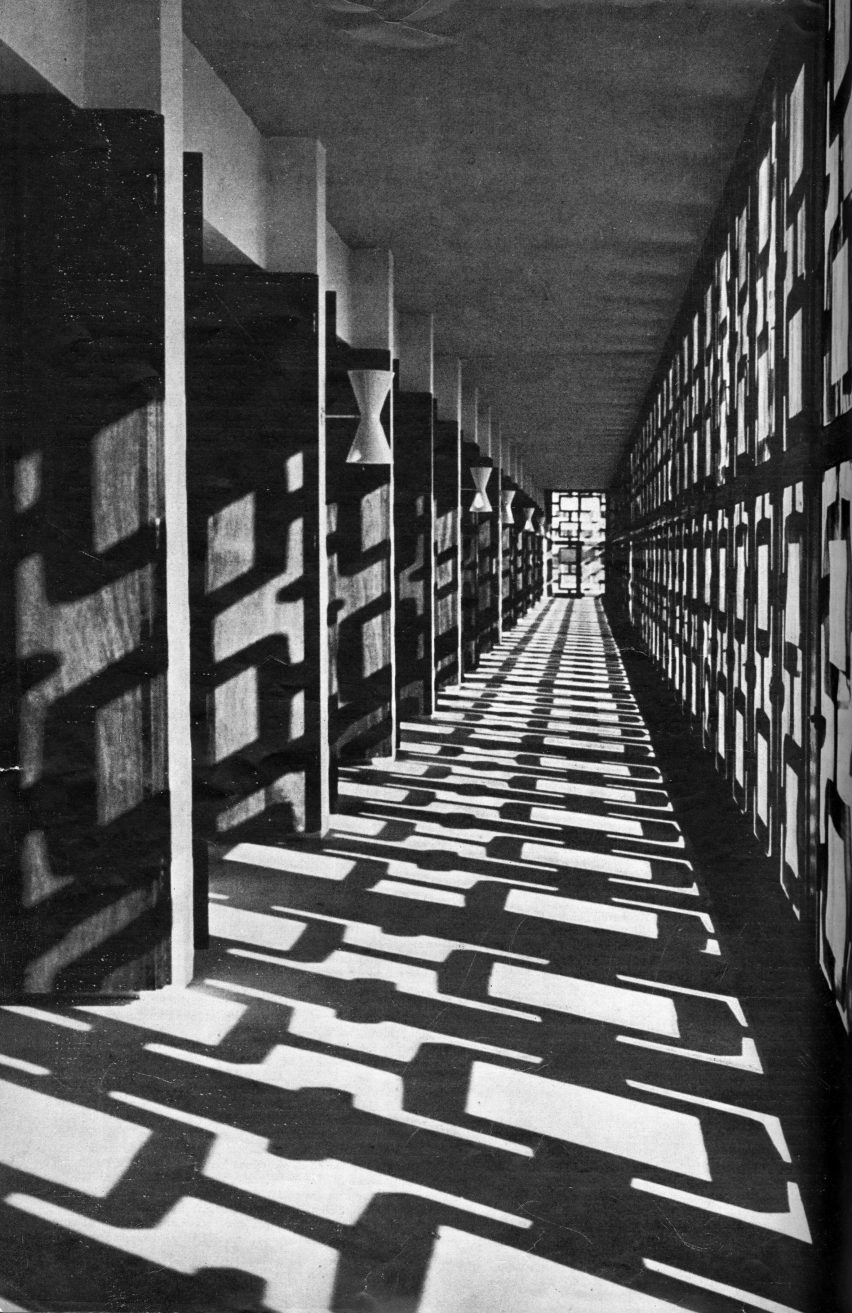

“Tropical modernism is experiencing something of a modish revival as an exotic and escapist style popular in verdant luxury hotels, bars and concrete jungle houses,” the exhibition’s lead curator Christopher Turner told Dezeen.

“But it has a problematic history and, through an examination of the context of British imperialism and the de-colonial struggle, the exhibition seeks to look at the history of tropical modernism before and after Independence, and show something of the politics behind the concrete,” he continued.

The exhibition follows the V&A’s Tropical Modernism exhibition at the 2023 Venice Biennale, which revealed the team’s precursory research on tropical modernism in a West African setting.

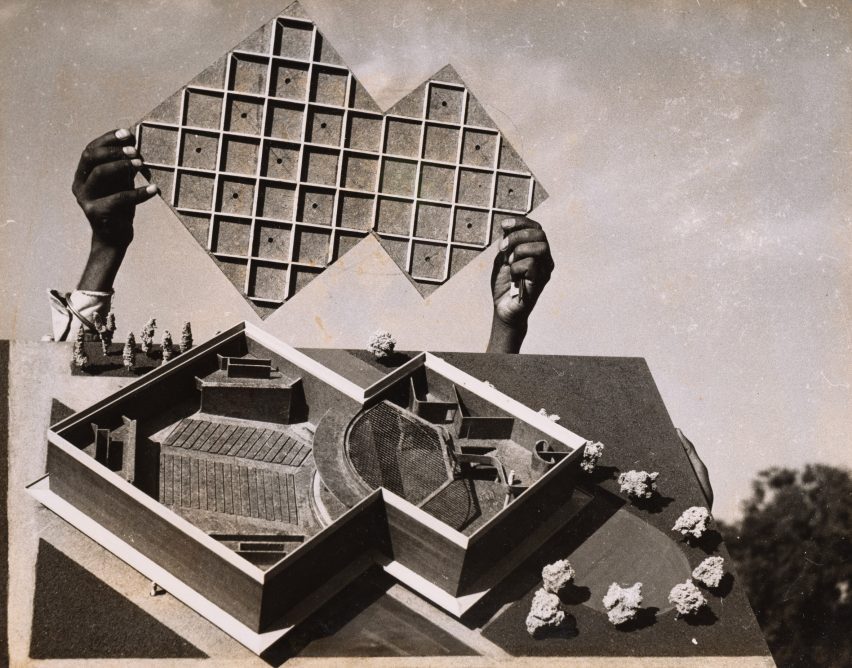

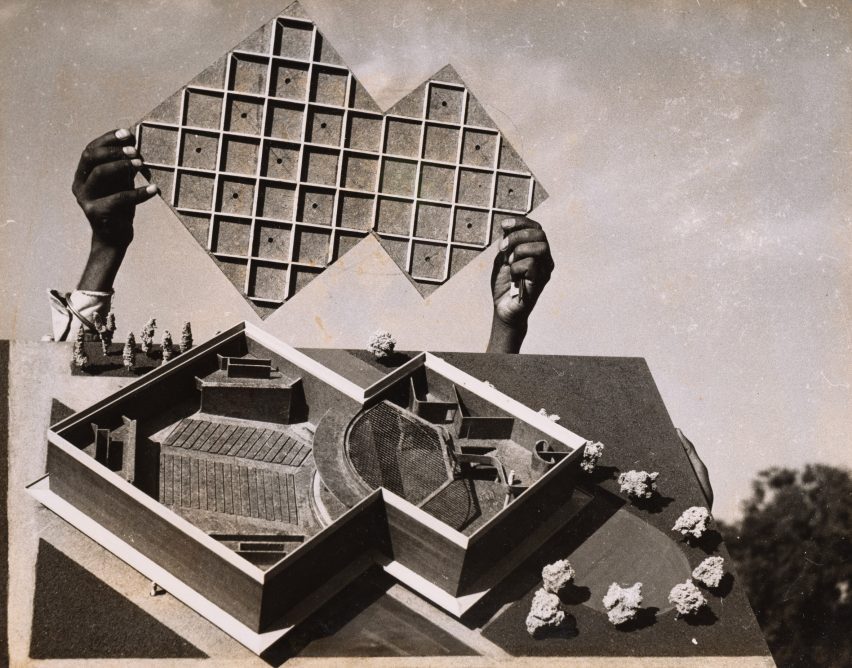

For the in-house iteration of the exhibition, additional architectural models, drawings and archival imagery have been introduced to interrogate tropical modernism in India alongside the African perspective.

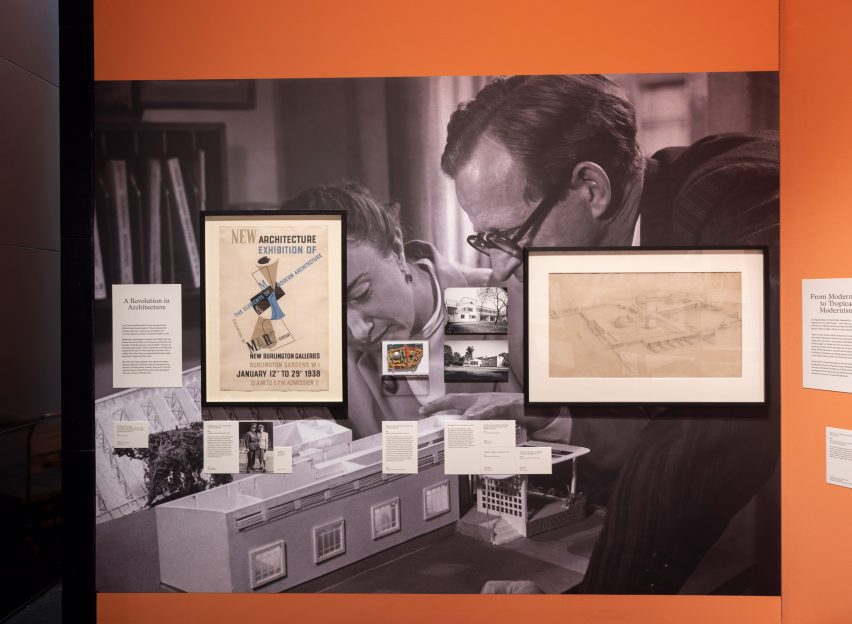

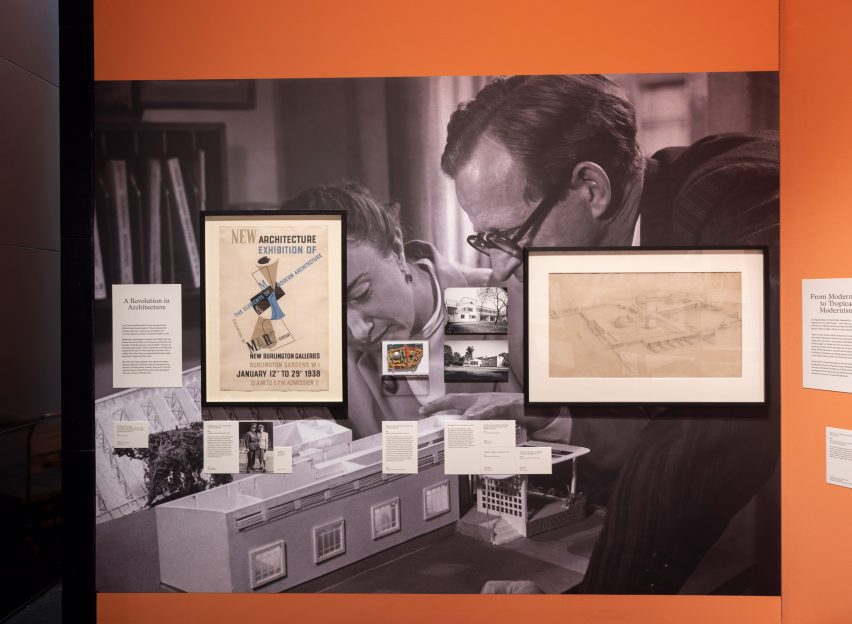

Exhibition materials line a series of rooms within the V&A’s Porter Gallery, divided by brightly coloured partitions and louvred walls referencing tropical modernist motifs.

The exhibition begins by tracing tropical modernism back to its early development by British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry. Stationed together in Ghana from 1944, Drew and Fry adapted international modernism to the African climate, proposing functional over ornamental design.

Drew and Fry would also become part of the Department of Tropical Studies at the Architectural Association (AA), which exported British architects to the colonies from 1954 in a bid to neutralise calls for independence.

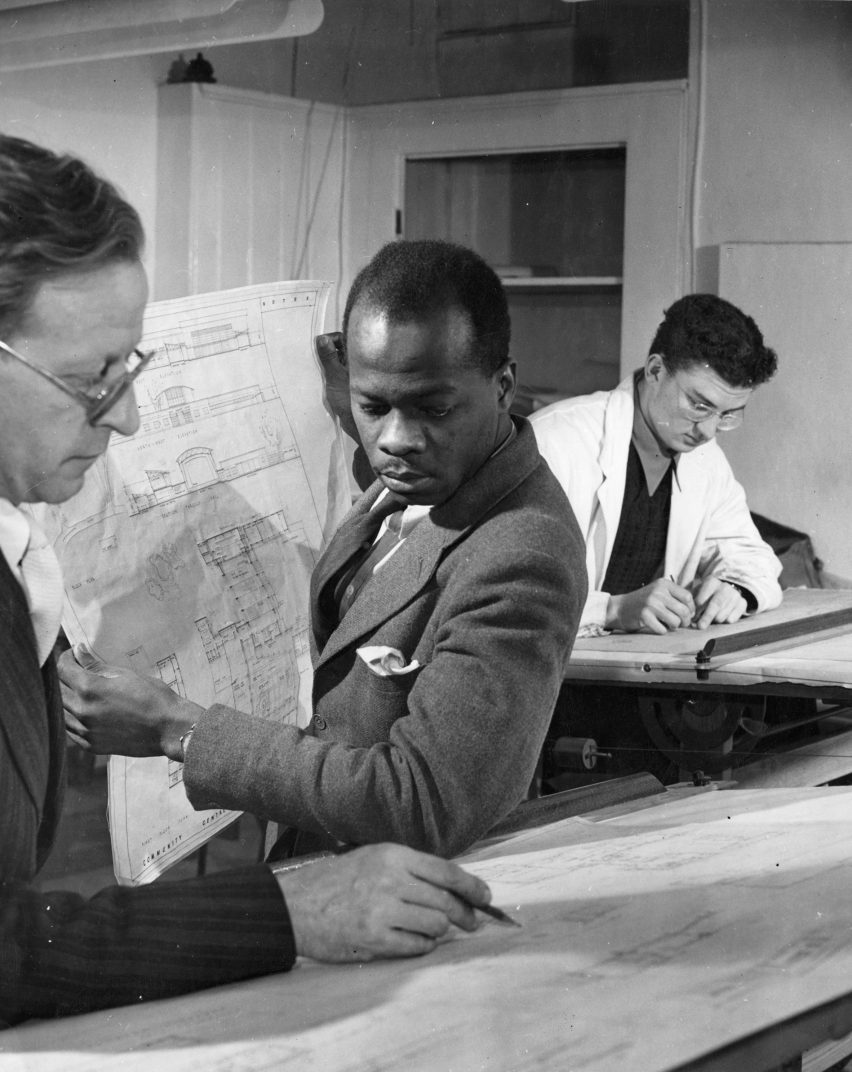

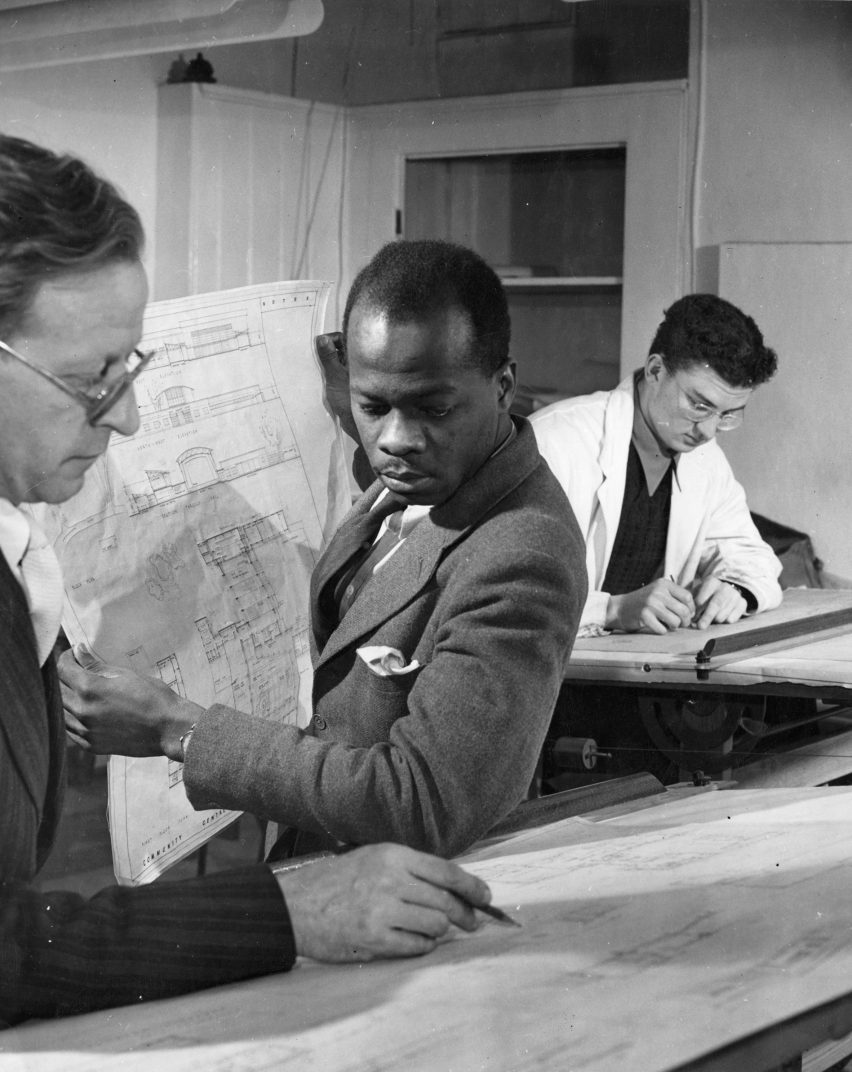

The exhibition continues by spotlighting local Ghanaian figures who worked with Fry and Drew, noting the power shifts that were taking place behind the scenes to reappropriate the architectural style for an emerging era of colonial freedom.

Influential political leaders Jawaharlal Nehru in India and Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana are the exhibition’s key personas, framing the evolution of tropical modernism from conception to regionalisation.

“The heroes of our exhibition are Nehru and Nkrumah, the first prime ministers of India and Ghana,” Turner explained. “Tropical modernism, a colonial invention, survived the transition to Independence and was appropriated and adapted by Nehru and Nkrumah as a tool of nation building.”

“Nkrumah, who sometimes sketched designs for the buildings he wanted on napkins, created the first architecture school in sub-Saharan Africa to train a new generation of African architects, and this institution has partnered with us on a five-year research project into tropical modernism.”

Through a host of physical models and artefacts, the city of Chandigarh becomes the exhibition’s narrative focal point for tropical modernism in India.

Under prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Chandigarh was the first large-scale modernist project, recruiting Drew and Fry along with French architect Le Corbusier to plan the ideal utopian urban centre.

As with Nkrumah – who saw how the Africanisation of architecture could become a symbol of progress and change – the exhibition also aims to highlight Nehru’s ambitions for a localised modernism drawing from the Indian vernacular, rather than the Western Bauhaus style.

The display culminates in a video featuring 16 key tropical modernist structures, interspersed with interviews and footage explaining the social and political context behind each building’s realisation.

“We made a three-screen 28-minute film, shot in Ghana and featuring panoramic portraits of over a dozen buildings, cut with archive footage from the time and interviews with architects like John Owusu Addo and Henry Wellington, and Nkrumah’s daughter, the politician Samia Nkrumah,” said Turner.

According to Turner, the exhibition begins to address gaps in the V&A’s collections and archives pertaining to architecture and design in the global south.

“Archives are themselves instruments of power, and West African and Indian architects are not as prominent in established archives, which many institutions have now realised and are working to address,” Turner explained.

“Tropical modernism was very much a co-creation with local architects who we have sought to name – all of whom should be much better known, but are excluded from established canons.”

Bringing tropical modernism back into contemporary discourse was also important to the V&A as a timely investigation of low-tech and passive design strategies.

“Tropical modernism was a climate responsive architecture – it sought to work with rather than against climate,” Turner said.

“As we face an era of climate change, it is important that tropical modernism’s scientifically informed principles of passive cooling are reexamined and reinvented for our age,” he added.

“I hope that people will be interested to learn more about these moments of post-colonial excitement and opportunity, and the struggle by which these hard-earned freedoms were won.”

The V&A museum in South Kensington houses permanent national collections alongside a series of temporary activations and exhibitions.

As part of London Design Festival 2023, the museum hosted a furniture display crafted from an Alfa Romeo car by Andu Masebo and earlier in the year, architect Shahed Saleem created a pavilion in the shape of a mosque at the V&A as part of 2023’s Ramadan Festival.

The photography is courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence will run from 2 March to 22 September 2024 at the V&A Museum in London. For more events, exhibitions and talks in architecture and design visit the Dezeen Events Guide.