Liquid City: A Radical New Masterplan in Rotterdam Embraces the River for Resilience

Architizer is thrilled to announce the winners of the 11th Annual A+Awards! Interested in participating next season? Sign up for key information about the 12th Annual A+Awards, set to launch this fall.

Popular with hip foodies and craft beer lovers, Fenix Food Factory’s generous outdoor seating area overlooks Rijnhaven. An old industrial harbor, over decades, it has seen shipping disappear under the boot of urban development.

After docklands moved west towards, and now into, the North Sea, a new district has sprung up in this corner of Rotterdam, extending the city center. Shops, residential blocks, floating structures housing offices and hospitality have replaced redundant warehouses and cranes.

The stunning Hotel New York overlooks all of this new development. The iconic building dates to the late-19th century, when it housed Holland America’s headquarters. The ocean liner route to Hoboken, New Jersey, carried close to 500,000 passengers from mainland Europe in its first twenty-five years of operation, and some will be immortalized when the FENIX Museum of Migration opens in 2024.

At the closed end of the quay, early signs of Rijnhavenpark are materializing — if you know what to look for. A large section of the harbor is cordoned off with buoys, and machinery has arrived to start the mammoth task of filling in one-third of the basin to create a huge public park, partly built on dry land, part floating on water, connected by walkways. The scheme is just one of several remarkable undertakings by the municipality of Rotterdam, transforming how the city interacts with its riverfront.

Rijnhaven, Rotterdam by Ossip van Duivenbode/Rotterdam Partners

Artist’s impression of Rijnhavenpark by City Projects/Rotterdam Partners

A delta town, the surrounding region of the Netherlands is home to the huge Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta, and has seen vast amounts spent on flood defences as a result. Known as Delta Works, modern protective infrastructure first broke ground in 1954 and construction only finished around 1997. Rotterdam’s Maeslantkering was one of the final pieces in a jigsaw of sluices, locks and dams. An enormous floodgate that took six years to build, it remains one of the planet’s largest moving structures.

A new masterplan comprising a series of large scale City Projects for central Rotterdam, many of which actively embrace the river itself, serves as a clear reminder of how vulnerable a city is when large parts lie below sea level — however, it also serves as a source of inspiration for design ingenuity. This scheme includes planting flora at different tidal levels, meaning that green spaces change with the time of day and actively supporting aquatic life, mammals and birds in the process.

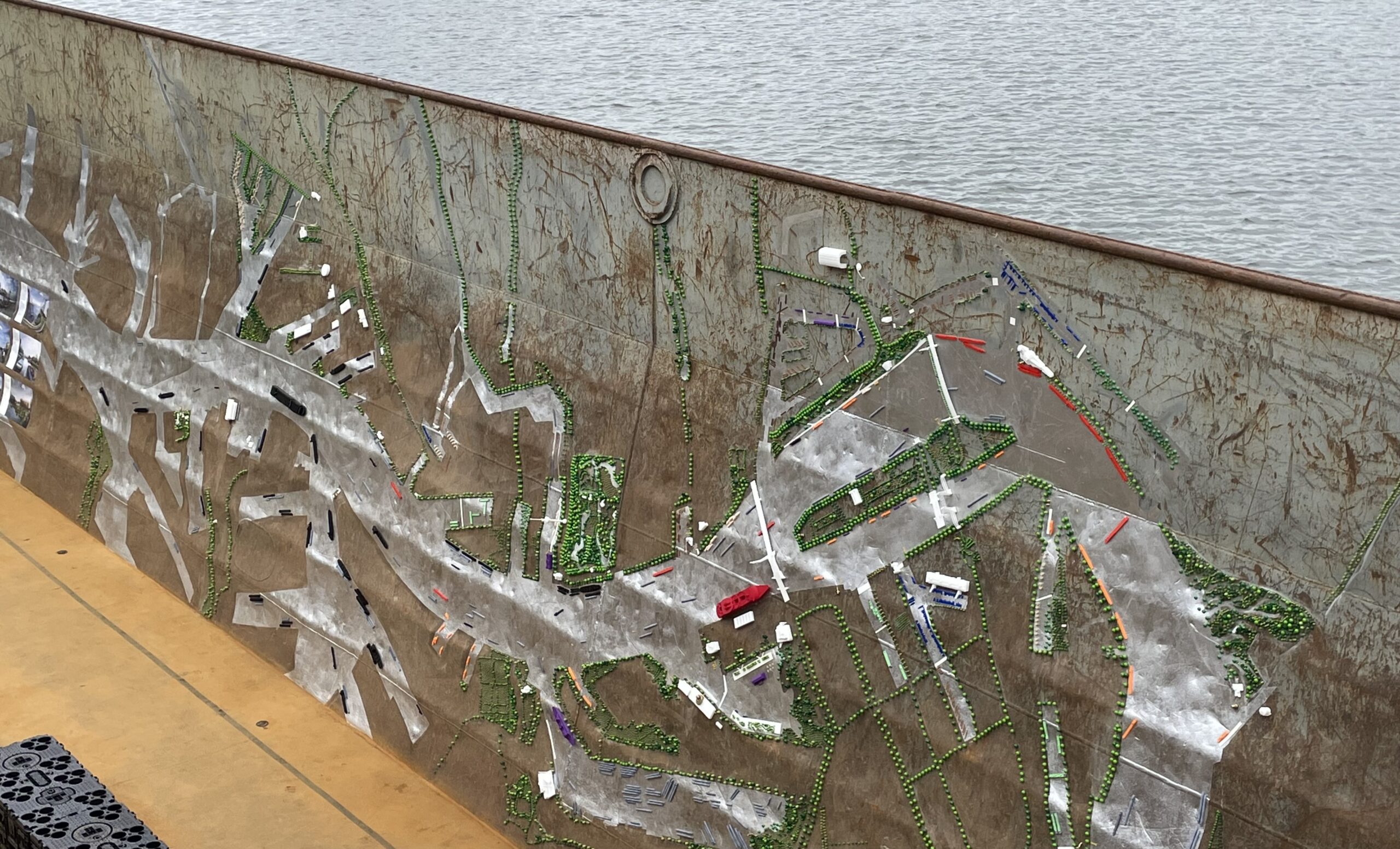

In total, eight sites have been approved, but the initial series could be the start of something far bigger — a vast ‘central park’ running down both river banks. This vision was creatively displayed on the inside of a disused shipping barge during June’s Rotterdam Architecture Month for the Liquid City exhibition. Should that ever materialize, the network of green waterfronts would line downtown and a good chunk of the former docklands that made up Europe’s largest port.

Interconnected green spaces are shown on the banks of the Meuse at Rotterdam Architecture Month by Martin Guttridge-Hewitt

“Four and a half years ago the decision was made that we need more green, and a lot more. Not just around the Meuse, but everywhere. Of course you can’t do it everywhere. So we were told there would be eight locations in the city centre, and to go away, do some homework quickly as possible, and present a study, with numbers for what it might cost,” explains Emiel Arends, urban planning specialist on City Projects who also works as part of Rotterdam’s climate adaptation programme, WeerWoord [Weatherwise]. “We only had four months to prepare, pitched it, they said OK, here’s €350 million ($387 million), go make it happen as soon as possible.”

In addition to riverside sites, City Projects also include the elevated Hofbogenpark, a narrow 1 mile (2 kilometer) micro-intervention on a former railway viaduct, and Hofplein, where urban greening will transform an already-busy square. Arends’ colleague, Pieter de Greef, senior planner and a key architect of the river-as-park masterplan, says the biggest challenge is Nelson Mendelapark. In partnership with US waterfront specialist SWA/Balsley, work has begun on an area the size of ten soccer fields at Maashaven harbour. Once complete, this will comprise hills, trees, lawns, an event space, and various tidal features, including a pathway designed to help people understand the river’s natural flow and ecosystem.

Artists impression of Nelson Mandelapark by SWA/Balsley

“If you want square meters, Tidal Park Feyenoord is bigger. But that’s all about biodiversity, greening rivers, giving nature new places in the city… it’s not for picnics and other activities,” says de Greef of the largest approved City Projects development. “Mandelapark is much more mixed. There’s a lot of social housing around there, which is good but they do not have many balconies or public spaces. The streets are narrow, filled with asphalt and stones. This project gives 16,000 households a large green space within 10 minutes walk.”

Unsurprisingly, considering the neighborhood’s urgent needs, de Greef says the most significant achievement with Nelson Mandelapark has been keeping all available land public. Other schemes in City Projects have integrated private interests to help finance. For example, at Rijnhavenpark three large residential blocks will deliver 4,500 homes, bringing in revenue to realise the vision. Elsewhere, water companies support schemes where green-blue infrastructure can ease pressure on overloaded drainage systems.

“Each part of the City Projects has a slightly different focus,” says Arends. “So within the inner city, on the north side, a little bit further away from the river, it’s about water storage and heat reduction. Tidal Park Feyenoord is all about biodiversity, but you can walk there as well. There are actions specific to each of the parks. It’s an insane programme. I’ve never seen this before, in any city.”

Hero Image: Rotterdam’s Maeslantkering flood defences by Guido Pijper / Rotterdam Partners

Architizer is thrilled to announce the winners of the 11th Annual A+Awards! Interested in participating next season? Sign up for key information about the 12th Annual A+Awards, set to launch this fall.