Architectural Drawings: Lithuania Reimagines Home Design in Plan

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Lithuania is home to breathtaking landscapes. From iconic sand dunes along the Curonian Spit to vast wetlands and primeval forests, the country is known for its beautiful and diverse countryside. Conscious of this context, Lithuania’s residential projects are designed to capture views and open up to the outdoors. Today, architects and designers are imagining new home designs in the “land of endless forests” for both rural and urban dwellings alike.

Exploring Lithuania’s inventive residential designs, the following projects showcase new approaches through plan drawings. Each house has a unique take on circulation and bringing people together, with residences found everywhere from the ancient forests of the Moletai region to Kaunas, Trakai and Vilnius. Reinventing traditional construction techniques and vernacular buildings traditions, these elegant homes make space for contemporary life and celebrate the beauty of Lithuania.

Villa The Lake

By Devyni architektai, Molėtai, Lithuania

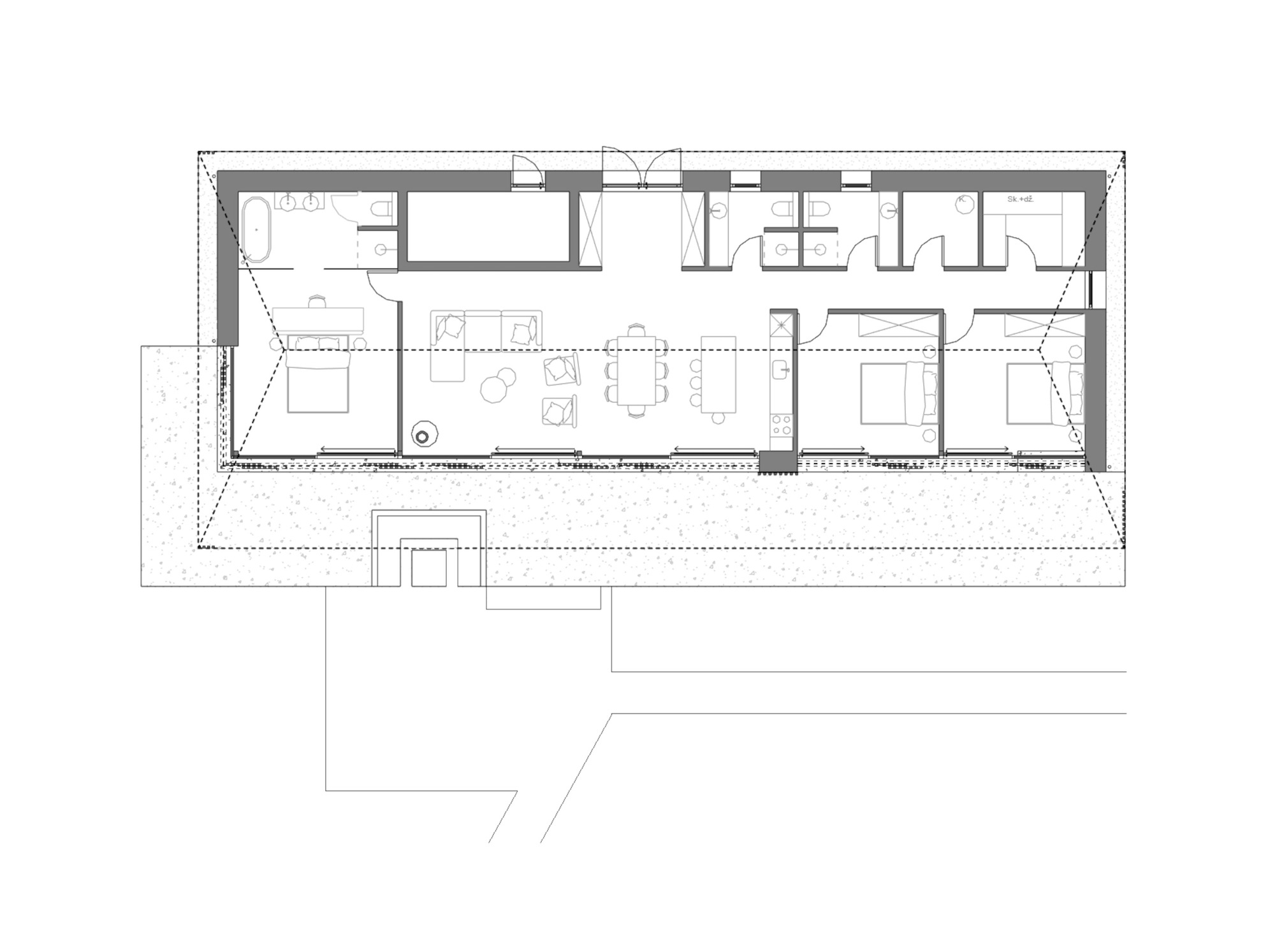

This residence was designed so that clients could enjoy the crystal-clear waters of a lake surrounded by ancient forests in the Moletai region of Lithuania. The villa consists of 4 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms and an open-concept dining area connected to the living room. Rectangular in plan, the dwelling has cutouts and sloped roofs that combine in a sculptural way. This layout prioritizes connection to the landscape and indoor-outdoor living.

This residence was designed so that clients could enjoy the crystal-clear waters of a lake surrounded by ancient forests in the Moletai region of Lithuania. The villa consists of 4 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms and an open-concept dining area connected to the living room. Rectangular in plan, the dwelling has cutouts and sloped roofs that combine in a sculptural way. This layout prioritizes connection to the landscape and indoor-outdoor living.

Large windows and sliding doors connect the house’s rooms with concrete terrace, grassy property and the dock. As seen in plan, a series of frames and a simple layout direct the focus towards the lake. The building was also designed with materials that echo the region’s agrarian typologies. Three primary materials were used for the building: wood, which forms many of the walls; slate tiles, which are used in the exposed roof; and concrete for the terrace.

An Autograph Among The Pine Trees

By ARCHISPEKTRAS, Kaunas, Lithuania

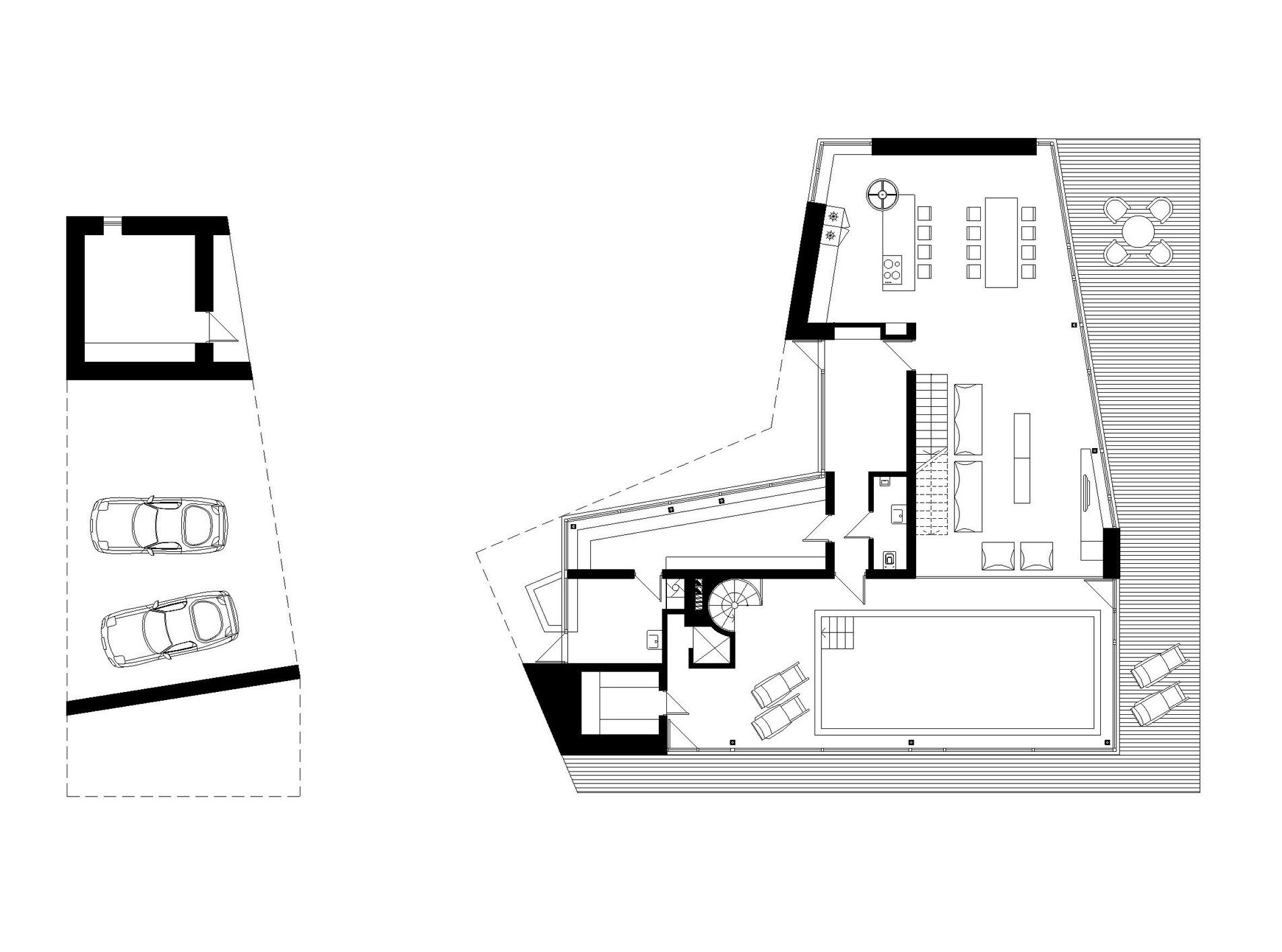

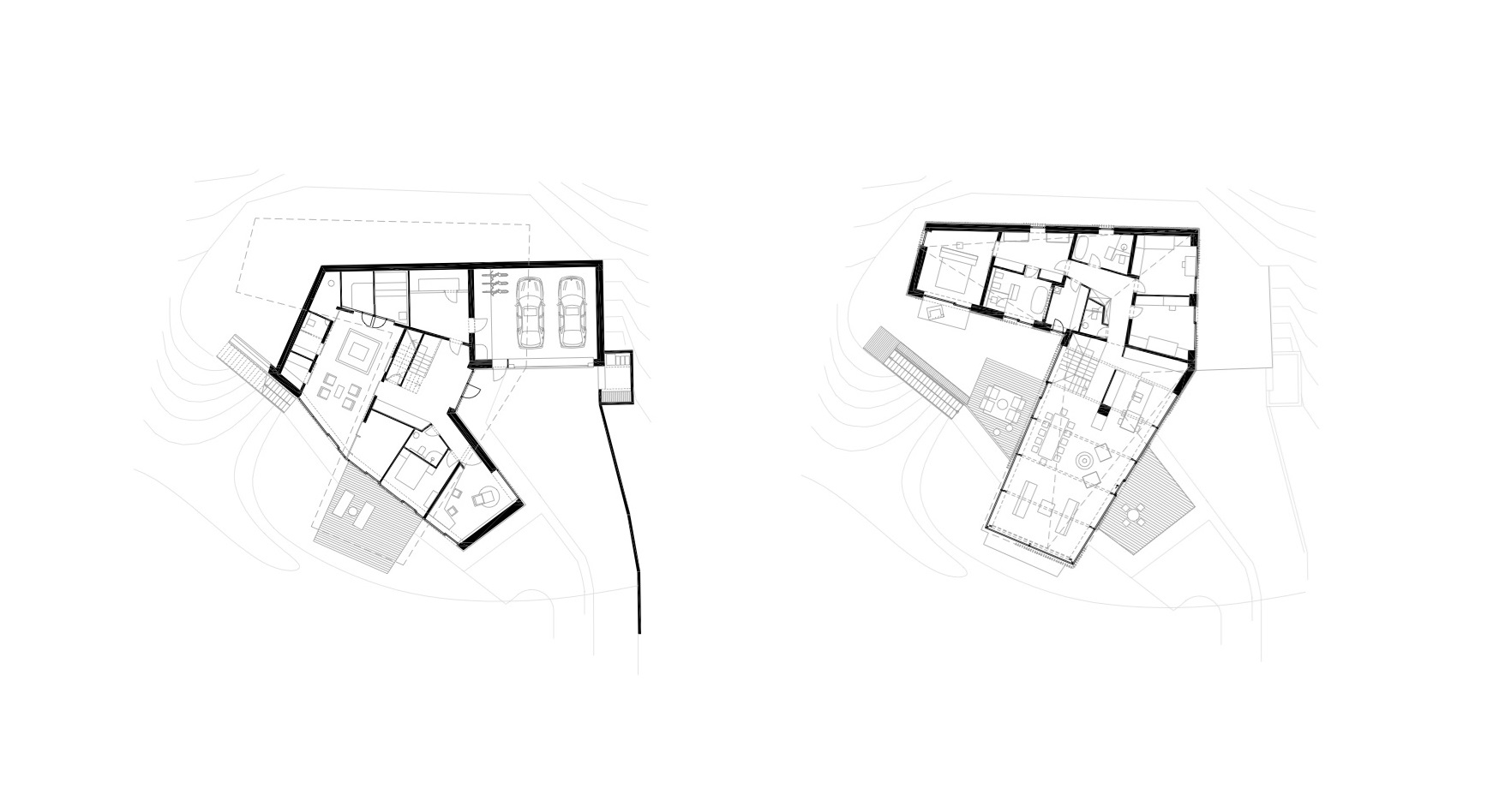

Situated on the river shore, this home was made of glass and rusted steel planes mounted in vertical segments. The plan is organized around this, opening up to the surroundings. For the materials, the idea is to have a metaphorical relation with the growing pine trees on the site. The rough concrete texture left by the formwork is the main interior expression. In addition, transparent and smooth glass surfaces ae widely used, making the interior feel visibly closer to nature.

Situated on the river shore, this home was made of glass and rusted steel planes mounted in vertical segments. The plan is organized around this, opening up to the surroundings. For the materials, the idea is to have a metaphorical relation with the growing pine trees on the site. The rough concrete texture left by the formwork is the main interior expression. In addition, transparent and smooth glass surfaces ae widely used, making the interior feel visibly closer to nature.

Made as a counterbalance to the factory-like interior, natural wood elements were abundantly used. Solid oak appears throughout and is seen in the monumental kitchen on the ground floor, as well as stairwell walls, floors, ceilings, cabinets and doors. It extends to cabinets which, like solid wood boxes, are designed without handles, hinges or other elements in order to completely keep a minimalist style. Attention is focused on the beauty of natural materials.

House in Trakai

By Aketuri Architektai, Trakai, Lithuania

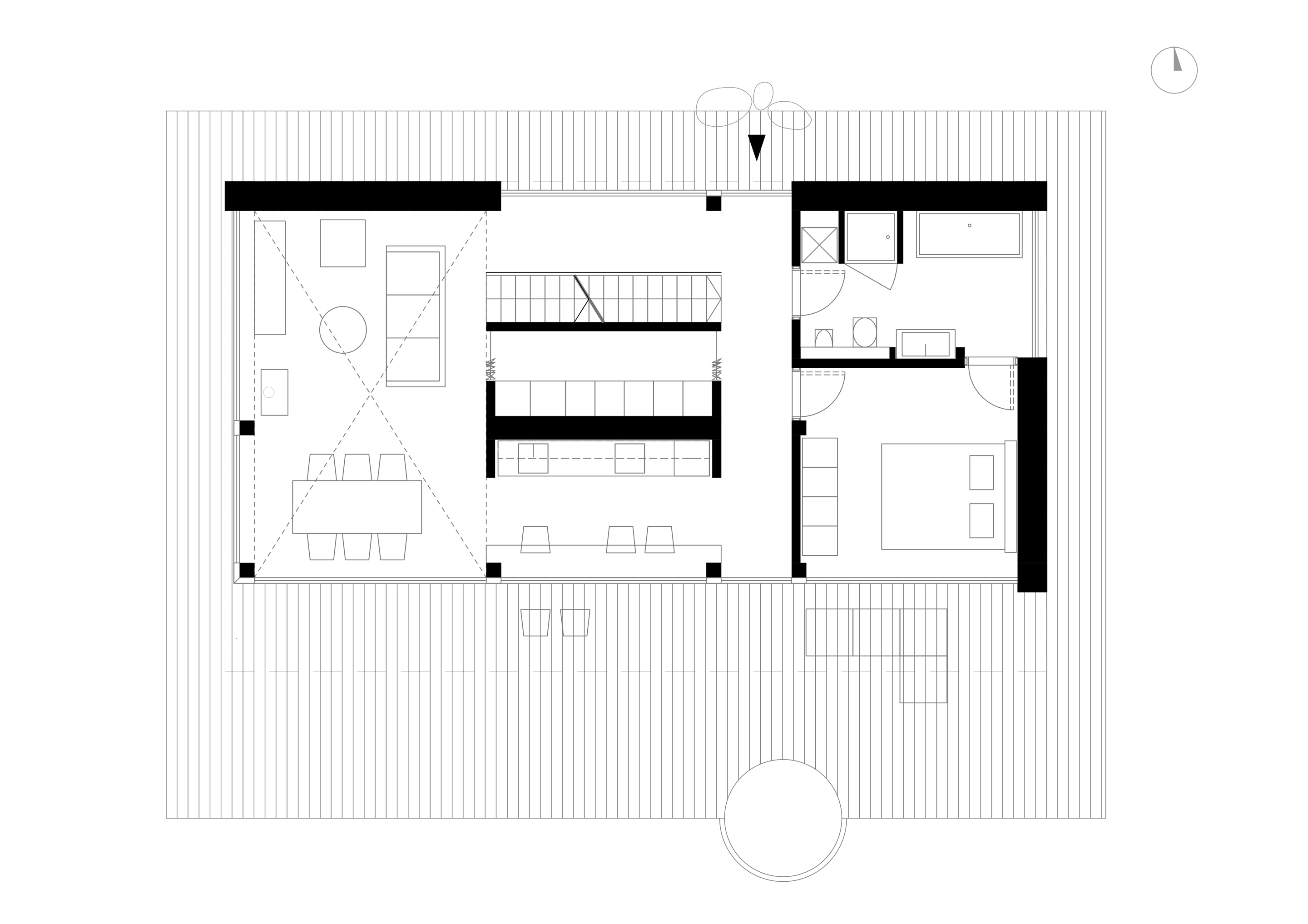

The House in Trakai was a study in clear geometry and vertical space. In Lithuania, there are clear depictions and traditions of the country-house. A vernacular idea, the design team wanted to make their own fresh take on this classic. In plan, this takes the shape of a rectangular footprint set on a deck, while the section is an extruded “house” profile with a steep roof pitch. “Everything that a family might need to relax in the natural surroundings fits into a modest archetypical volume with no sacrifice of comfort.”

The House in Trakai was a study in clear geometry and vertical space. In Lithuania, there are clear depictions and traditions of the country-house. A vernacular idea, the design team wanted to make their own fresh take on this classic. In plan, this takes the shape of a rectangular footprint set on a deck, while the section is an extruded “house” profile with a steep roof pitch. “Everything that a family might need to relax in the natural surroundings fits into a modest archetypical volume with no sacrifice of comfort.”

For the team, the project is all about connecting with nature — the limit between the forest and the house disappears due to sliding translucent panels. For the materials, thermowood and shale require as little maintenance as possible, giving the residents more time to connect with their surroundings.

The L house

By PAO Architects, Vilnius, Lithuania

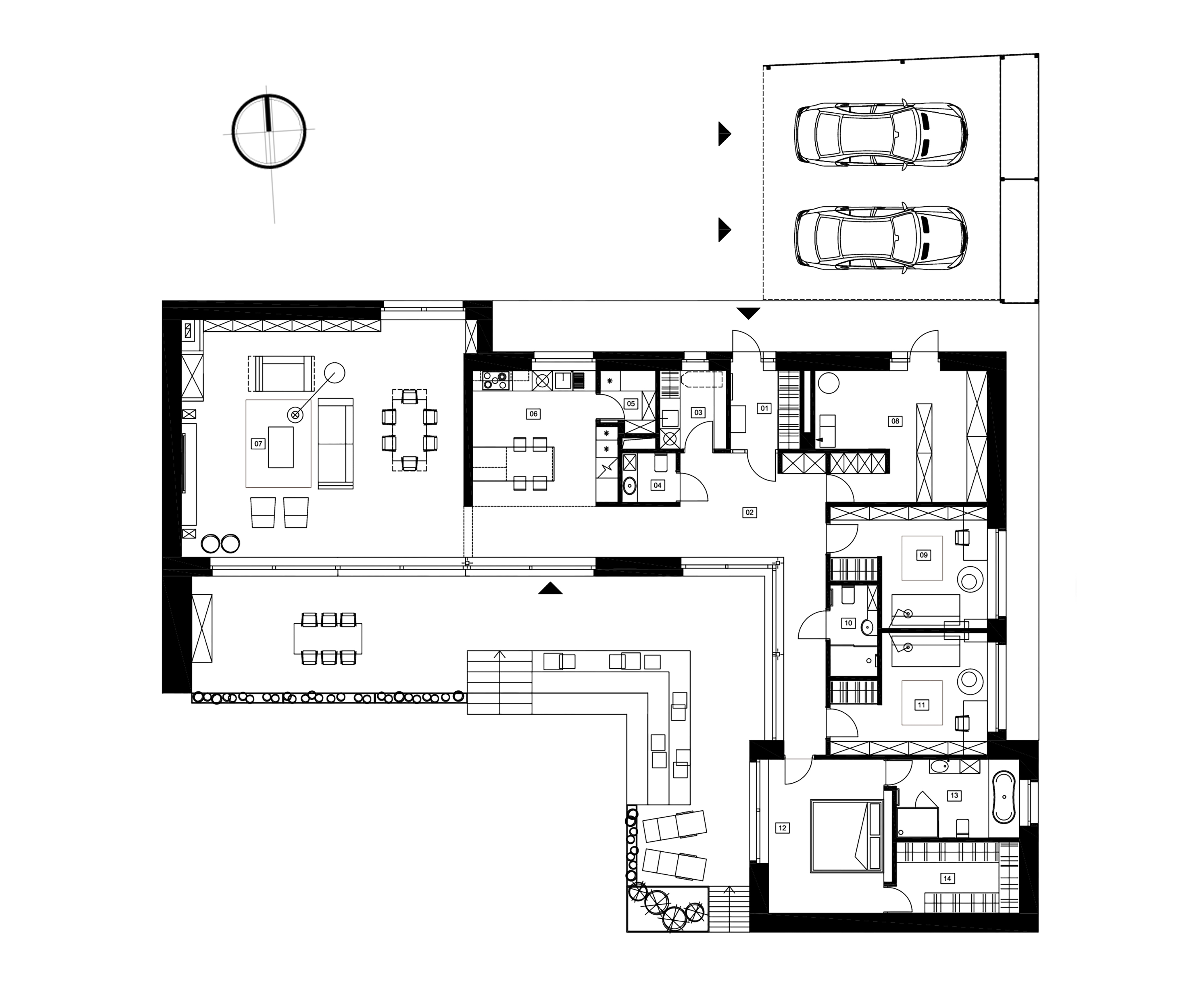

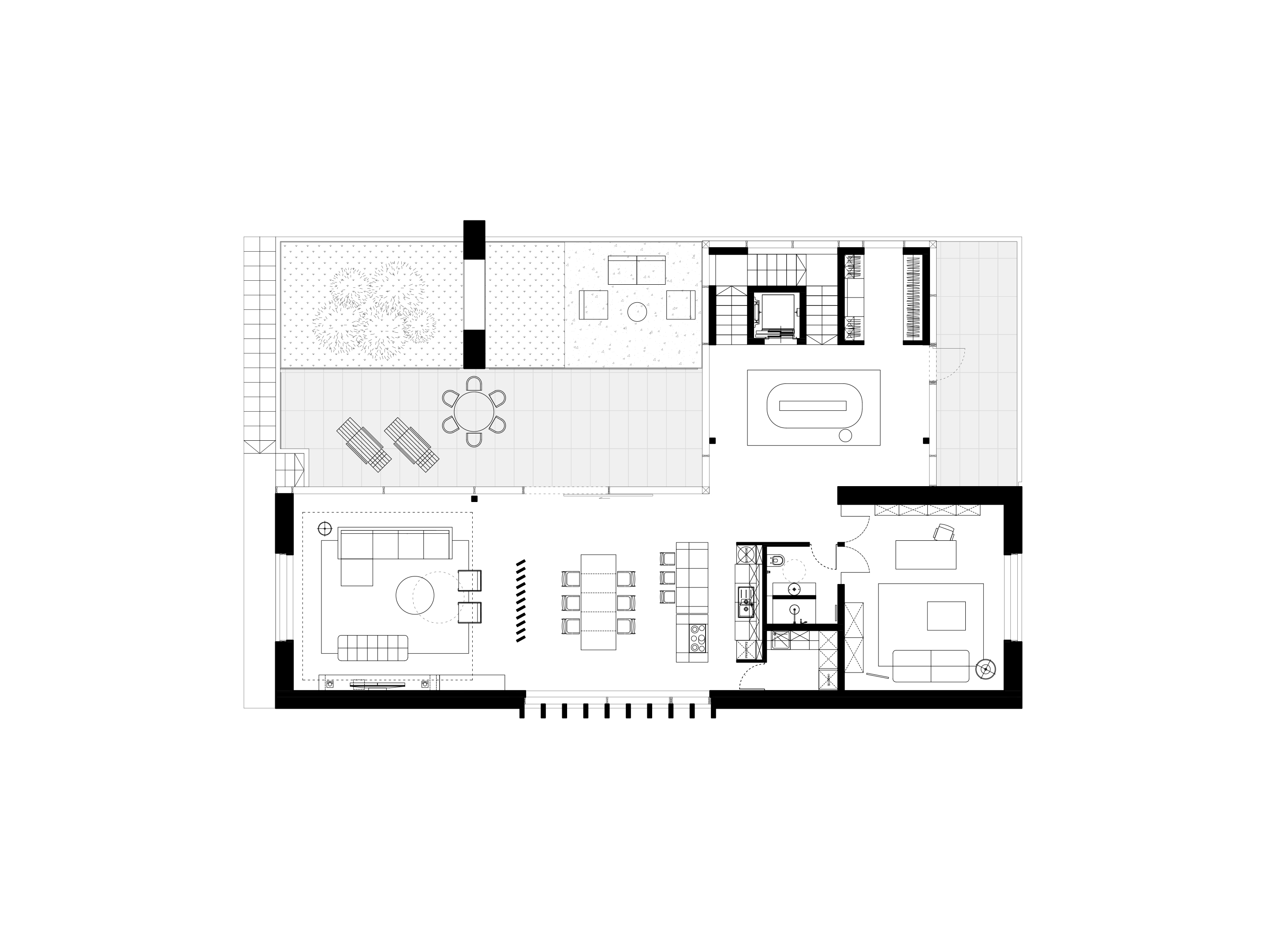

True to its name, the L House is directly tied to its shape in plan. The residence was built for a private client based in Vilnius, Lithuania. When the team started the project, the architects were inspired by the beauty of the site and its relationship with nature. The central concept and guiding principle was the desire to maintain a delicate balance between nature. The result is the subtle volume of the building, a single story house.

True to its name, the L House is directly tied to its shape in plan. The residence was built for a private client based in Vilnius, Lithuania. When the team started the project, the architects were inspired by the beauty of the site and its relationship with nature. The central concept and guiding principle was the desire to maintain a delicate balance between nature. The result is the subtle volume of the building, a single story house.

The design team used only natural finishes, bricks and wood to keep a contemporary and sustainable approach. Large windows keep a relationship between the environment and indoor spaces. Site volume and terraces above provide a unique expression of the entire building. The L-shaped structure of the house forms a functional connection between the building and landscape. In turn, the building is oriented such that the living room, kitchen and hall windows face the south, which is formed by a large courtyard.

Residential House in Palanga

By Architectural bureau G.Natkevicius and partners, Palanga, Lithuania

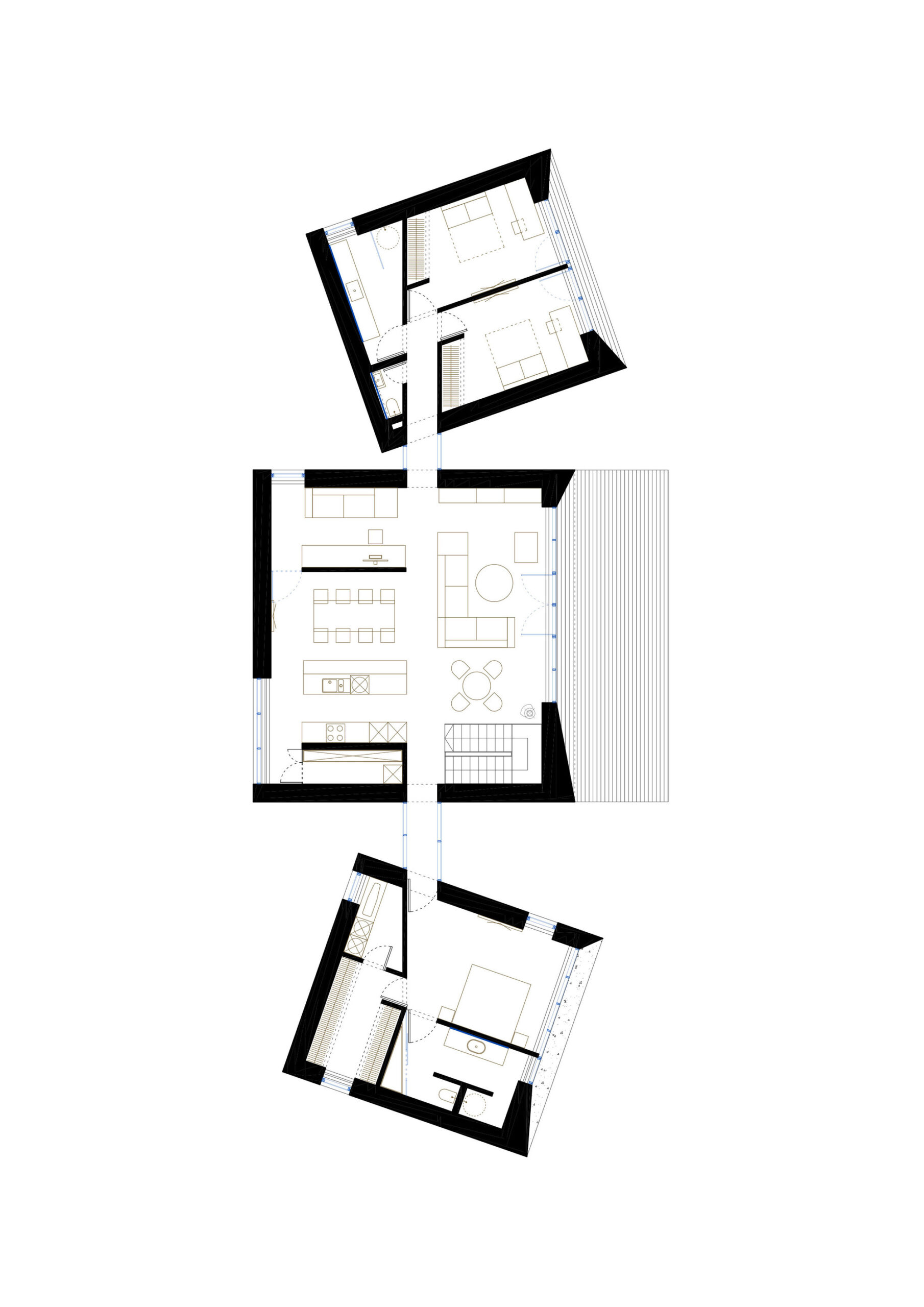

For this four-member family house, the project was located in the seaside resort town of Palanga. It features a slope and is framed by a forest wall on top of the hill. All living spaces are lifted above the street level and focused on the forest, while the utilitarian spaces are positioned on the lower level. The scheme was divided into three separate volumes corresponding with three functional zones.

For this four-member family house, the project was located in the seaside resort town of Palanga. It features a slope and is framed by a forest wall on top of the hill. All living spaces are lifted above the street level and focused on the forest, while the utilitarian spaces are positioned on the lower level. The scheme was divided into three separate volumes corresponding with three functional zones.

Children rooms with a dedicated bathroom and washroom are situated firmly on the ground, while the parents’ zone — a master bedroom with ensuite facilities — is lifted on a tower leg, which serves as a storage space. The central zone houses a stairway, the main living areas on the first floor and a garage, an entrance hall and technical spaces on the ground floor. This dismantling of the scheme allowed for delicate adjustments of orientation across the residential plan.

Valley Villa

By arches, Vilnius, Lithuania

Valley Villa is an iconic home in Lithuania. Just a few hundred meters from an active city street, the home is located on a sunny slope near the outskirts of town. It is designed in place of a former farmstead. A key goal was to maintain the existing slope on site and to preserve as many trees as possible The idea of the building was to “hang” it over the valley and open the building up with continuous windows. Due to the black shale finish, the ground floor seemingly disappears in shadow.

Valley Villa is an iconic home in Lithuania. Just a few hundred meters from an active city street, the home is located on a sunny slope near the outskirts of town. It is designed in place of a former farmstead. A key goal was to maintain the existing slope on site and to preserve as many trees as possible The idea of the building was to “hang” it over the valley and open the building up with continuous windows. Due to the black shale finish, the ground floor seemingly disappears in shadow.

With implications in plan, the design reinterprets the silhouette of a traditional sloped house. The divided volume, varying forms, human scale proportions, glass and wood all come together to create the impression of lightness. Interior spaces follow the forms of the volume, while a natural wood finish for the façades and roof creates the impression of solidity. By dividing the volume, micro-spaces and courtyards are created.

Birdhouse

By YCL studio, Vilnius, Lithuania

YCL’s Birdhouse residence is located among a dense block of private houses in Vilnius. The key wish from the clients was to have a big common space not divided by stairs in any way. So the team chose to move the stairs out of the main perimeter of the house, a guiding idea in plan. This creates a shape that looks different when walking around the house. The north part of the house with the stairs has just one round window, like a birdhouse that waits for its dwellers.

YCL’s Birdhouse residence is located among a dense block of private houses in Vilnius. The key wish from the clients was to have a big common space not divided by stairs in any way. So the team chose to move the stairs out of the main perimeter of the house, a guiding idea in plan. This creates a shape that looks different when walking around the house. The north part of the house with the stairs has just one round window, like a birdhouse that waits for its dwellers.

Mirrored details across the house were an illusion to reflect the changing surroundings. The dark wood façade also creates a color change to form a dialog with the surroundings. The garage volume formed a private separation from the neighboring plot, but at the same time it was not attractive to have that volume in a private yard. So the team mirrored it, and through another kind of illusion, extended the yard.

House in Kaunas

By Architectural bureau G.Natkevicius and partners, Kaunas, Lithuania

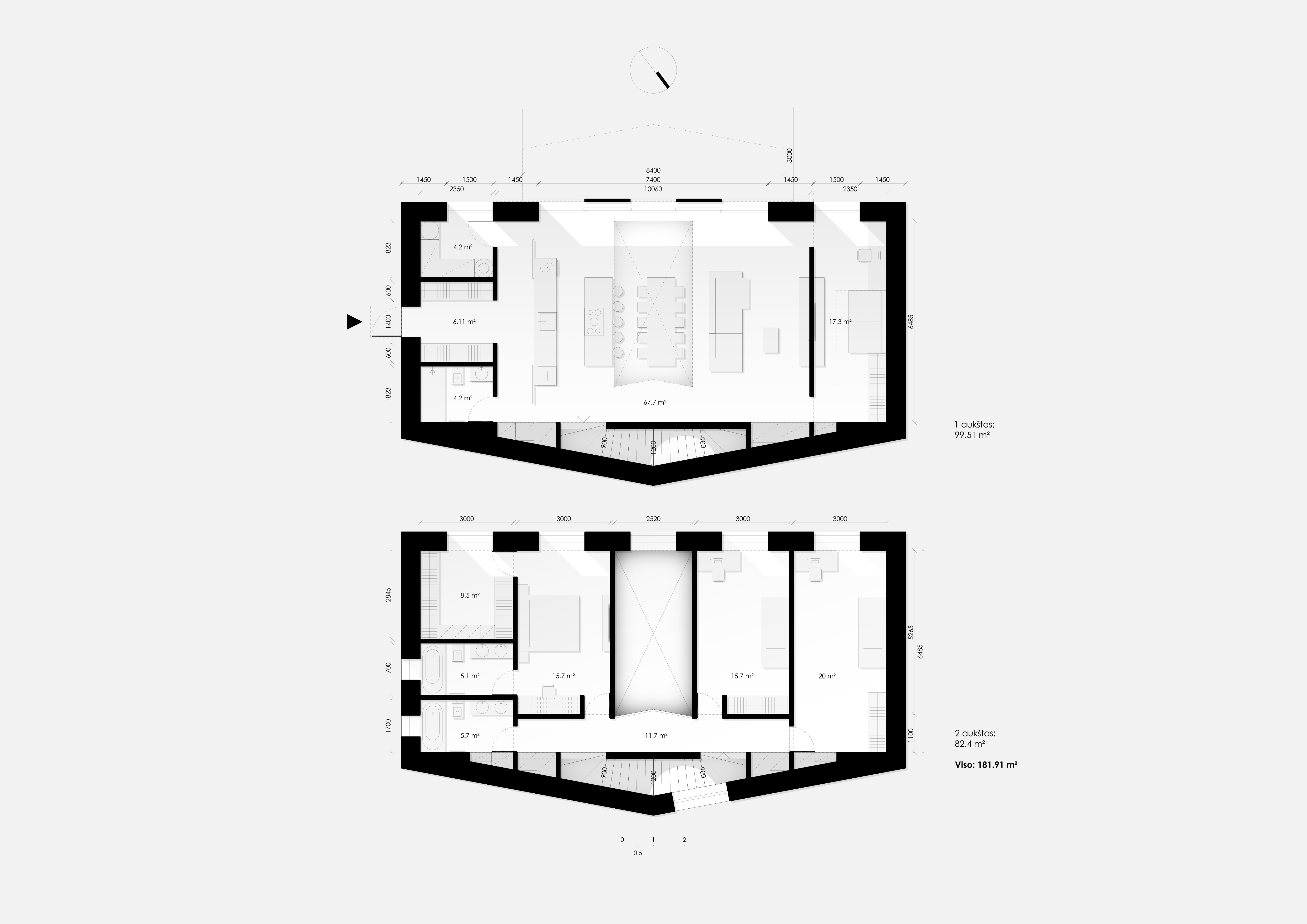

Understanding the potential of vertical living and monumental expression, this two-story home with a basement is located in the picturesque central district of Kaunas. The composition of the house keeps the spirit of Kaunas modernism alive as the circular windows in the concrete planes give the impression of modernism. At the same time, the two-volume reinforced house further highlights and accentuates the slope of the plot.

The volume of the building is divided into three floors. The first level is an access to the basement of the house, where a luxury garage for eight cars was designed. The staircase from the partially open basement leads to the first floor of the building and the inner space of the plot. Once entering the building the upper level and inner space opens – the inner yard and the terrace further enhance the impression of the levitating volume. The terrace is also designed with a rectangular concrete support with a circular opening that echoes the façade.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

As the centerpiece of the Des Moines Western Gateway Park urban renewal project, this public library was sited between the center of the city and a newly designed public park. As well as library facilities, the building contains a flexible activity space, education facilities, children’s play areas, a conference wing and a cafeteria. In plan, it responds to the orthogonal nature of the city blocks to the east while stretching out into the park to the west. This plan is extruded vertically with a glass-metal skin, which gives the building its distinctive appearance.

As the centerpiece of the Des Moines Western Gateway Park urban renewal project, this public library was sited between the center of the city and a newly designed public park. As well as library facilities, the building contains a flexible activity space, education facilities, children’s play areas, a conference wing and a cafeteria. In plan, it responds to the orthogonal nature of the city blocks to the east while stretching out into the park to the west. This plan is extruded vertically with a glass-metal skin, which gives the building its distinctive appearance.

Harkening back to the beginning of insulated glazing itself, the Halley VI Antarctic Research Station was designed for polar research. As the world’s first re-locatable research facility, it was constructed by Galliford Try for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). The project aimed to demonstrate ground-breaking architecture characterized by a compelling concept, but also a structure that’s executed with careful attention to detail and coordination.

Harkening back to the beginning of insulated glazing itself, the Halley VI Antarctic Research Station was designed for polar research. As the world’s first re-locatable research facility, it was constructed by Galliford Try for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). The project aimed to demonstrate ground-breaking architecture characterized by a compelling concept, but also a structure that’s executed with careful attention to detail and coordination.

Extending an existing university gymnastic hall with a testing laboratory, the Damesal project was designed with a new building on top. The project offered an opportunity to explore an architectural concept where the geometry of the additional floor is designed with a simple box shape in glass. The architectural and functional variation happens as the glass façade responds to the program and functions within the building. The building’s envelope embodies design and performance as a collaboration between the architect and the supplier of the customized glass solution.

Extending an existing university gymnastic hall with a testing laboratory, the Damesal project was designed with a new building on top. The project offered an opportunity to explore an architectural concept where the geometry of the additional floor is designed with a simple box shape in glass. The architectural and functional variation happens as the glass façade responds to the program and functions within the building. The building’s envelope embodies design and performance as a collaboration between the architect and the supplier of the customized glass solution.

The Greenpoint Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Station was designed as a two-story facility that supports FDNY ambulance crews and vehicles. The project was made with a strong, distinctive form occupying a prominent site in the rapidly developing neighborhood. The station’s requirements led to a four-part division of the facility. Because the space for housing vehicles called for a higher ceiling height than the rest of station, one side is taller than the other. This change organizes the building’s functions.

The Greenpoint Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Station was designed as a two-story facility that supports FDNY ambulance crews and vehicles. The project was made with a strong, distinctive form occupying a prominent site in the rapidly developing neighborhood. The station’s requirements led to a four-part division of the facility. Because the space for housing vehicles called for a higher ceiling height than the rest of station, one side is taller than the other. This change organizes the building’s functions.

The Koch Center was designed to provide advanced integrative healthcare and complex outpatient services. Patient-centered and family-centered care is at the forefront of the building’s medical program, announced by a triple-height lobby that offers respite from the surrounding streets. Infusion and radiation oncology areas, as well as diagnostic imaging, typically found in basement areas, are located on upper floors. This gives patients and staff the benefit of natural light.

The Koch Center was designed to provide advanced integrative healthcare and complex outpatient services. Patient-centered and family-centered care is at the forefront of the building’s medical program, announced by a triple-height lobby that offers respite from the surrounding streets. Infusion and radiation oncology areas, as well as diagnostic imaging, typically found in basement areas, are located on upper floors. This gives patients and staff the benefit of natural light.

SHA designed the Cité de l’Océan et du Surf museum to raise awareness of oceanic issues and explore educational and scientific aspects of the surf and sea. Centered around leisure, science, and ecology, the project was made in collaboration with Solange Fabião. The design includes the museum, exhibition areas, and a plaza, within a larger master plan. The building form derives from the spatial concept “under the sky”/“under the sea”.

SHA designed the Cité de l’Océan et du Surf museum to raise awareness of oceanic issues and explore educational and scientific aspects of the surf and sea. Centered around leisure, science, and ecology, the project was made in collaboration with Solange Fabião. The design includes the museum, exhibition areas, and a plaza, within a larger master plan. The building form derives from the spatial concept “under the sky”/“under the sea”.

Paul Keskeys: Congratulations on your success! What does winning the 2022 One Rendering Challenge mean to you?

Paul Keskeys: Congratulations on your success! What does winning the 2022 One Rendering Challenge mean to you? What were the primary challenges of conceiving your work, from forming the idea to the actual physical process of rendering?

What were the primary challenges of conceiving your work, from forming the idea to the actual physical process of rendering? Did you use your usual techniques and software for creating this rendering? If you tried something different, how did that go?

Did you use your usual techniques and software for creating this rendering? If you tried something different, how did that go?

What one tip would you give students and architects looking to win next year’s One Rendering Challenge?

What one tip would you give students and architects looking to win next year’s One Rendering Challenge?