Allbirds releases “world’s first net-zero carbon shoe”

At the Global Fashion Summit in Copenhagen, Allbirds has unveiled a woolly sock-style trainer with a bioplastic sole that effectively adds zero emissions to the atmosphere over the course of its life, the shoe brand claims.

The minimal all-grey Moonshot sneaker features an upper made using wool from a regenerative farm in New Zealand, which uses sustainable land management practices to capture more carbon than it emits.

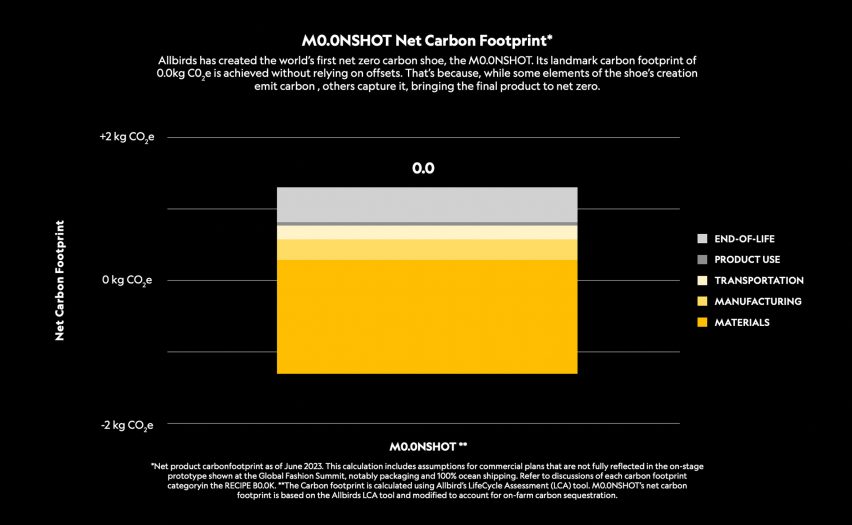

This on-farm carbon storage offset any other emissions generated over the product’s lifecycle, Allbirds claims, making it the “world’s first net-zero carbon shoe”.

“Regenerative wool was a critical pillar of helping us reimagine how products are designed and made through the lens of carbon reduction,” co-founder Tim Brown told Dezeen.

“To me, the currently untapped opportunity for naturally derived, net-zero products is the future of fashion.”

Allbirds races to reduce trainers’ footprint

Set to launch commercially next spring, the product follows in the footsteps of the Futurecraft.Footprint trainer, which at 2.94 kilograms CO2e was reportedly the lowest-carbon trainer ever made when Allbirds and Adidas launched it in 2021.

Back then, the team focused mainly on simplifying the construction of trainers, which have an average footprint of 13.6 kilograms CO2e, and reducing the number of separate components from 65 to just seven.

This same principle was also applied to the Moonshot, which features no laces or eyelets and integrates its insole directly into the knitted upper.

But this time, the key advance came in the form of materials – primarily the merino wool upper sourced from Lake Hawea Station, a certified net-zero farm in New Zealand.

Through regenerative practices such as replanting native trees and vegetation, as well as maintaining soil carbon through rotational grazing, the farm says it sequesters almost twice as much carbon as it emits.

However, these carbon benefits of sustainable land management are generally not considered in a material’s lifecycle assessment (LCA).

“Frequently, the way that the carbon intensity of wool is looked at is just acknowledging the emissions, so completely disregarding any of the removals happening on farm,” said Allbirds sustainability manager Aileen Lerch. “And we think that that is a huge missing opportunity.”

That’s because it prevents brands, designers and architects, who are increasingly making use of biomaterials to reduce the footprint of their projects, from reliably calculating and certifying any emissions savings.

With the Moonshot project, Allbirds hopes to offer a template for how these carbon benefits could be considered within LCAs, using Lake Hawea Station’s overall carbon footprint as a basis.

From this, the Allbirds extrapolated a product-level footprint for the wool, which the company has so far failed to disclose, using its own carbon calculator.

As a result, there is a degree of uncertainty around the actual footprint of the trainer because it cannot currently be verified by a third party according to official international standards.

But Allbirds head of sustainability Hana Kajimura argues that this is a risk worth taking to help push the discussion forward and incentivise a shift towards regenerative agriculture.

“It’s about progress, not perfection,” she said. “We could spend decades debating the finer points of carbon sequestration, or we can innovate today with a common sense approach.”

Plastics still play a role for performance

Regenerative wool also cannot yet fully contend with the performance of synthetic fibres, meaning that to create the Moonshot upper, it had to be blended with some recycled nylon and polyester for durability and stretch.

For the midsole, Allbirds managed to amp up the bioplastic content from 18 per cent in 2021’s Futurecraft.Footprint trainer to 70 per cent in the Moonshot, using a process called supercritical foaming.

This involves injecting gas into the midsole, making it more durable and lightweight while reducing the need for emissions-intensive synthetic additives.

“In the industry right now, most midsoles have no bio content or quite a minimal one,” Lerch explained. “So it’s really a large step change in what’s possible because of this supercritical foaming process.”

Stuck to the front of the sneaker is a bioplastic smiley face badge by California company Mango Materials, which is made using captured methane emissions from a wastewater treatment facility that is then digested by bacteria and turned into a biopolyester called PHA.

The shoe itself will be vacuum-packed in bioplastic polyethylene to save space and weight during transport, which Allbirds plans to conduct via electric trucks and biofuel-powered container ships.

There is no “perfect solution” for end of life

Another area that will need further development is the end of life, meaning how the shoe’s packaging and its various plastic and bioplastic composite components can be responsibly disposed of given that they are notoriously hard – if not impossible – to recycle.

“We don’t yet have a perfect solution of what will happen at its end of life,” Lerch said. “We don’t want to make a promise of: send it back, don’t worry, buy your next shoe and move on.”

“We acknowledge though, that the answer isn’t just to keep making more products that end up in landfill or incinerated. So we’re continuously looking at what those solutions can be.”

In a bid to overcome challenges like this and encourage collaboration across the industry, Allbirds is open-sourcing the toolkit it used to create Moonshot and encouraging other companies to adapt, expand and improve on it.

“It is also about ushering in a new age of ‘hyper-collaboration’ across brands and industries to share best practice, build scale for all parts of the supply chain, to reward growers and lower costs,” Brown said.

Allbirds became the first fashion brand to provide carbon labelling for all of its products in 2020.

Since then, the company has committed itself to reducing the carbon footprint of its products to below one kilogram and its overall footprint to “near zero” by 2030.