We Are the Rare, Repeat Heat Pump Water Heater Customers

The word is now out, and sales of heat pump water heaters (HPWHs) are taking off. New rebates, mandates, and tax credits will likely drive sales through the roof by the end of this decade. Heat pump water heaters use a fraction of the energy of legacy technologies, with great performance, which means lower utility bills along with reduced carbon emissions. We’ve embraced the technology on our journey to electrify two different properties, and we were among the first in the US to buy and install a 120V plug-in heat pump water heater at our family home in Ohio.

Why do we sing their praises?

Cost!

The heat pump water heater is among the most affordable climate-saving technologies available. While solar panels and electric cars are vital tools for climate warriors, a heat pump water heater saves the energy equivalent of seven solar panels while costing only one-sixth the price. They run approximately $1600 for the appliance, plus $1000 to $3000 for installation, depending on the fuel your current water heater uses. This cost is higher than traditional gas or electric-resistance water heaters, but many utilities offer rebates to bring down the price. And then add the 30% tax credit from the Inflation Reduction Act, if the property is your primary residence.

If your current water heater is gas, you may need to run a 240V electrical line, unless you get a new 120V plug-in model (for more info on this option, read about our fourth install below). If your current water heater is electric-resistance, it should already have a 240V line running to it, likely allowing a simple swap.

Efficiency

Hot water accounts for a substantial share of energy use in buildings—17% in single family homes and up to 32% in multi-family—hundreds of dollars a year. Heat pumps move heat rather than create it. So heat pump water heaters are three to five times more efficient than standard water heaters. They look just like a legacy water heater, but a bit taller because the heat pump sits on top of the water tank.

They cost very little to operate: $100 to $150 a year for a family of four, saving $550 compared to an electric resistance water heater and $200 less than a gas water heater. A new heat pump water heater can pay for its higher upfront cost in just a few years. And then it’s saving you money each year after that.

Carbon

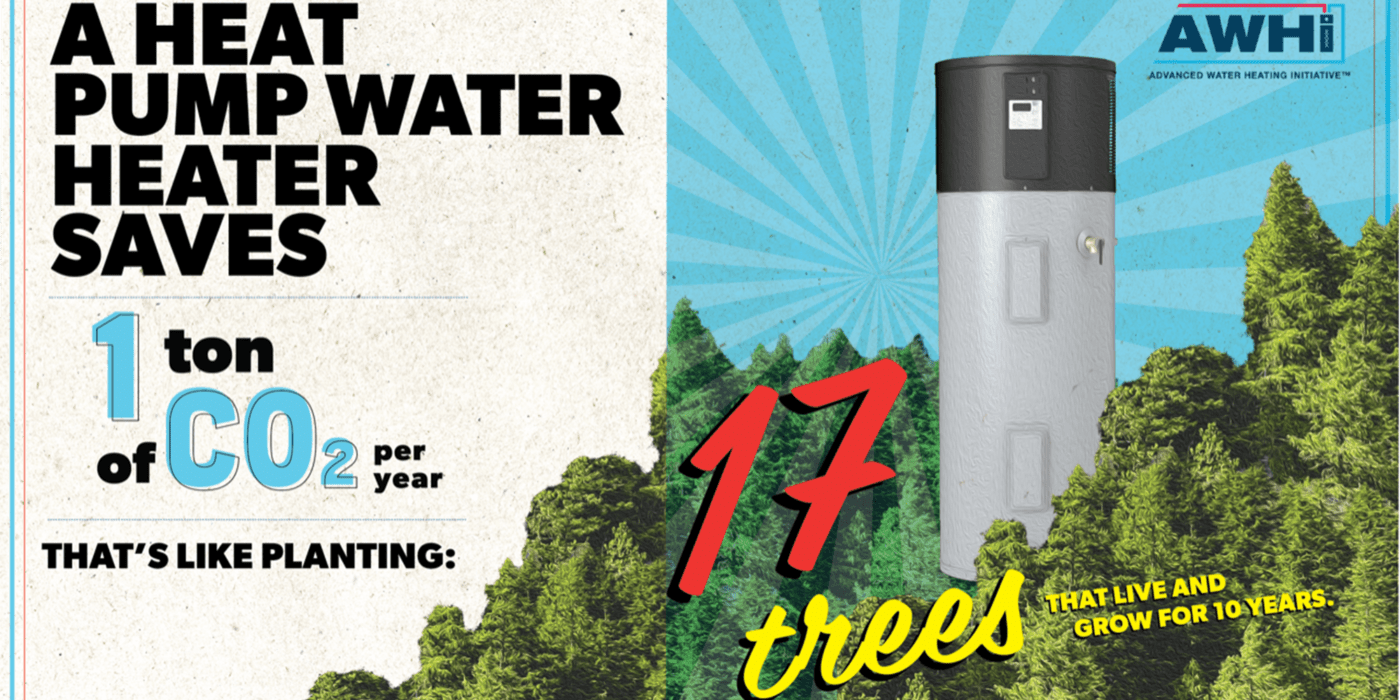

Sure heat pump water heaters are super energy efficient, but they also run on electricity, which means they can use renewable electricity. Replacing a single gas water heater with a heat pump unit will save around 1 ton of CO2 annually.

And the word is out. While heat pump water heaters currently account for only less than 2% of new water heater sales, they jumped 26% in 2022 as sales of natural gas water heaters fell. Heat pump water heaters could increase to half of all water heater sales by 2030.

Propelling electrification

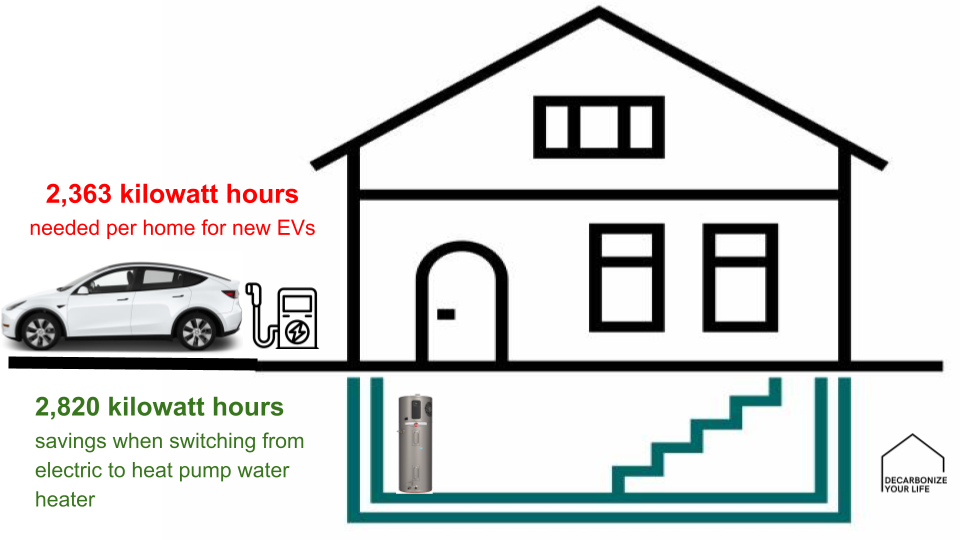

Electricity is the only widely-available, scalable fuel option that is quickly decarbonizing. So reducing climate change involves converting everything to highly efficient, clean electricity. A common critique of the electrification movement is that the electrical grid can’t handle the additional loads to replace fossil fuels used in buildings and transportation. Enter heat pumps. Widespread deployment of heat pumps in HVAC and hot water production will save tremendous energy: enough to power new electrical loads, like electric cars (EVs), on the existing grid.

Heat pump water heaters (HPWH) will likely save nearly all the electricity a household needs to operate an EV.

As Americans transition to EVs over the next decade, heat pump water heaters alone will likely save nearly all the electricity that a household needs to operate an EV. This statistic shows how much energy we currently waste in heating our water. And this EV electrical load is replacing carbon-intensive gasoline and diesel fuels.

About half of the US currently has electric resistance water heaters, so as those homes switch to heat pump water heaters, we won’t have to worry about finding more electricity for EVs. Their utility bills will likely stay constant, saving them all the money they currently spend at the gas pump.

The other half of homes heats water with fossil fuels, so we will need to find added clean electricity for those water heaters and vehicles. (But transitioning electric-resistance space heaters and clothes dryers to heat pump units produces savings similar to switching out water heaters.) Most heat pump water heaters run on 240V (the same as conventional electric water heaters and dryers), but if your old water heater runs on gas, you may have to install a new power line from the panel. But a 120V plug-in model is the newest option. If your current water heater is electric, it will likely be an easy swap: no need for an electrical panel upgrade or service upsize from the utility.

2017: HPWH replacing an aging water heater

Our old gas water heater was nearing its end of life, and Joe was excited about the technological advance of heat pumps for water heating. Though we still had questions about installation and performance.

It’s easiest to install a heat pump water heater in a basement or garage, because they exhaust cool air. But our heat pump water heater resides in a coat closet in the middle of our living space, venting into the attic. There it draws the warmest air in our house and exhausts to an unconditioned space. (Note that there are lots of options for locating heat pump water heaters in living spaces without ducting.)

Of course there were no local installers familiar with heat pumps back then, but after watching YouTube, Joe felt OK working with a trusted handyman. Even though it was a gas conversion, an existing 240V electrical line made things much easier. Ever since, this unit has consistently provided our family plus an Airbnb with plentiful hot water.

2019: HPWH replacing a functioning gas hot water heater

We did not get the full life out of the existing gas hot water heater in the accessory dwelling unit on our property. We chose to replace a perfectly good appliance (only 7 years old) with a heat pump water heater powered by clean solar energy. Our goal was to eliminate fossil fuels from our home. We used the same attic-ducting technique as the water heater in the main house, locating the unit in a closet. This mighty unit provides plenty of hot water for the tenant and runs the radiant floor heating system as well. (We don’t recommend heat pump water heaters for floor heating, as it is not a proven or scalable application.)

2020: HPWH replacing a decrepit gas water heater

During COVID, we undertook an interiors and sustainability renovation of a duplex in Cleveland, OH, that has been in our family for 75 years. In transitioning to all-electric, we replaced an almost 30-year-old basement water heater with our favorite heat pump. In addition to reducing our energy bill by $200 a year, it provides great dehumidification: about 2–4 quarts of water per day. If you currently run one or more dehumidifiers in your damp, Midwestern basement, you may save hundreds more.

The plumber added a new 240V power line, and ran the condensate tube to the floor drain. The basement maintains about 60 °F all winter, and we’ve never needed to engage the less-efficient backup electric-resistance heating elements.

2023: The new 120V heat pump water heater

This past summer, we replaced the other 30-year-old gas water heater in the basement of the Cleveland duplex. This just-arrived-on-the-market 120V unit eliminated the need to run 240V power from the panel. As heat pump enthusiasts, we were excited to test the latest tech. Perhaps the most difficult step was placing the custom order with Home Depot. Though now it’s readily available!

The installation was the easiest part. It took the plumber (who had never heard of a heat pump water heater) only 2.5 hours to complete the job, about the same as a standard gas water heater. The 120V heat pump water heater plugs right into a standard outlet. But he did have to run the condensate tube into the floor drain nearby and cap the gas line.

The 120V unit has been humming along for months—it’s very quiet—using a mere 65 kWh in the first month of operation. We monitor its performance through the manufacturer’s app, so we know it remains ridiculously efficient and almost always completely full of hot water. At a total of $3,258 installed and estimated savings of $208 a year. The 120V models usually eliminate the backup electric-resistance heating elements by using a larger tank with more hot water stored, or by storing water at higher temperatures and then mixing in cold water to avoid scalding. Our 120V unit uses the latter strategy; see it in action.

If this were our primary residence, we might have taken advantage of the 30% tax credits for heat pump water heaters, lowering our cost to $2,281. That comes so close to the $2,000 average installed cost of a standard gas or electric water heater. And you’re still saving hundreds of dollars a year on energy costs. This proves that almost any of the 60 million US homes with a gas water heaters can easily and cheaply move towards a cleaner, decarbonized home that is less expensive to operate.

We’re big fans of making a long-term decarbonization plan, so you’re not rushing to replace broken equipment and being forced to install new circuit breakers or even a new panel or expensive electrical service upgrade. So before checking the cost of a heat pump water heater, understand your home’s installation requirements and identify a contractor or two. Then when the time, and rebates and tax credits, are right, you’re ready to switch. Because they save so much on utility bills, proactively replacing a functioning, but inefficient, water heater with a heat pump water heater may make sense—for the sake of our changing climate.

This article springs from several posts by Naomi Cole and Joe Wachunas, first published in CleanTechnica. Their “Decarbonize Your Life” series shares their experience, lessons learned, and recommendations for how to reduce household emissions.

The authors: