Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Migration has long transformed Florida’s landscapes and architecture. In the last two years alone, more than 600,000 new residents came from other parts of the United States, and 175,000 people from other countries. Without this influx, Florida would not be growing. This mix of new people, cultures and ideas has continuously shaped design in cities across the state.

As an evolution of Florida’s vernacular structures, this new architecture is also a response to the state’s humid, subtropical climate. From early chickee (homes) by Seminole tribes to St. Augustine’s Gilded Age buildings to the present, architects have continued designing in respond to local conditions and aesthetic traditions. Increasingly, new civic and cultural buildings pay careful attention to the building envelope, materials and ventilation. Designed to make an impact, the following projects represent this wave of iconic architecture found across the Sunshine State.

L. Gale Lemerand Student Center | Daytona State College

By ikon.5 architects, Daytona Beach, FL, United States

ikon.5 designed the 74,000-square-foot L. Gale Lemerand Student Center at Daytona State College as a landmark on the Floridian shoreline. In their own words, the project “establishes an iconic presence to the campus” along the main arterial road connecting Daytona beach with the rest of Florida. The team’s approach takes the form of a curving stone and bronze wall with two outreached arms forming a welcome lawn at the campus entry.

ikon.5 designed the 74,000-square-foot L. Gale Lemerand Student Center at Daytona State College as a landmark on the Floridian shoreline. In their own words, the project “establishes an iconic presence to the campus” along the main arterial road connecting Daytona beach with the rest of Florida. The team’s approach takes the form of a curving stone and bronze wall with two outreached arms forming a welcome lawn at the campus entry.

As the team notes, rising from the center of the wall is a bronze portal framing the opening to the student center and giving passage to the main quadrangle and campus beyond. Internally, a three-story commons overlooks the quadrangle and serves as the campus living room. Custom bronze perforated solar screens help limit glare, while a ventilated bronze rain screen reduces heat gain in the harsh Florida sun.

Florida Polytechnic University

By Santiago Calatrava, Lakeland, FL, United States

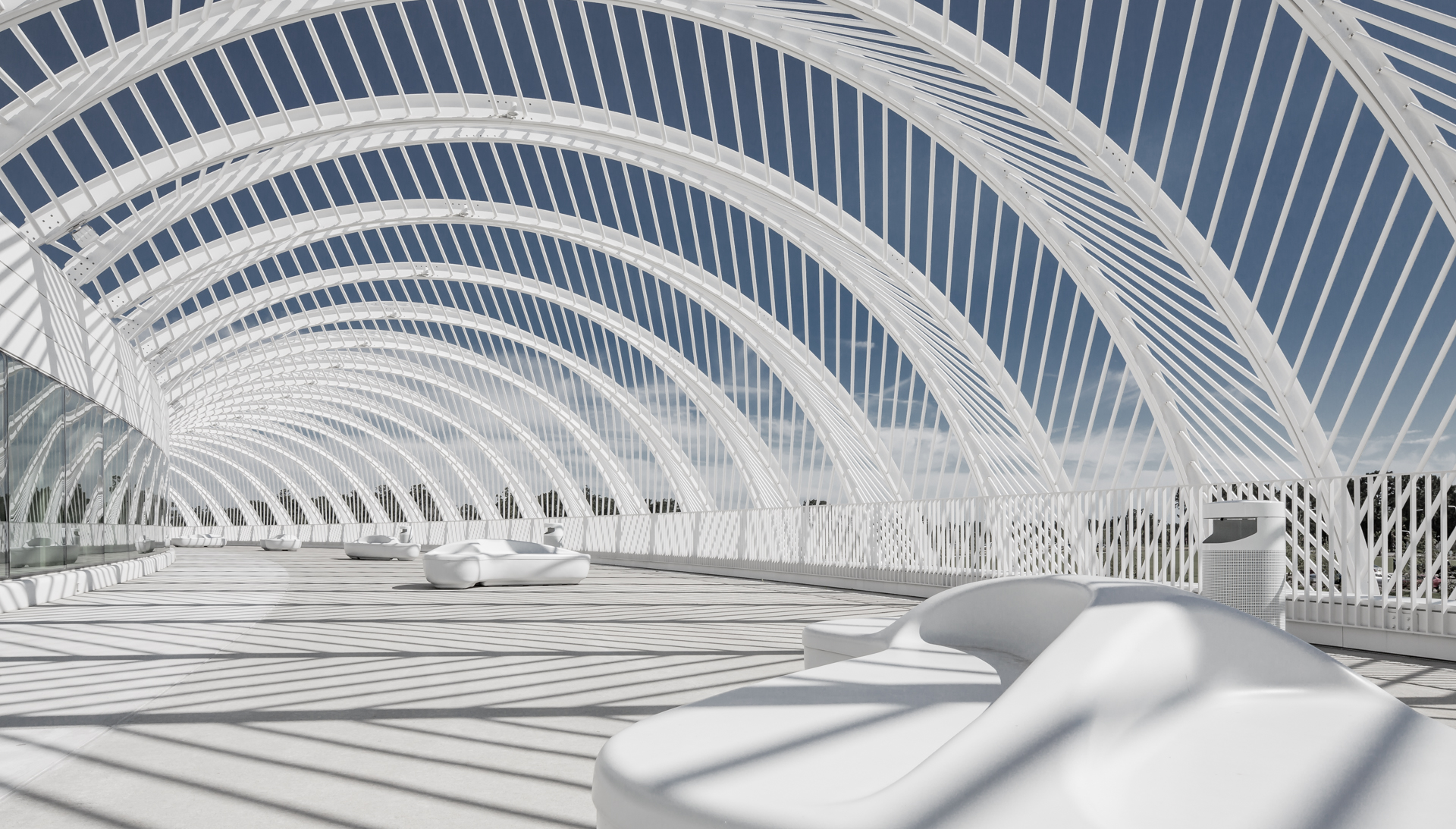

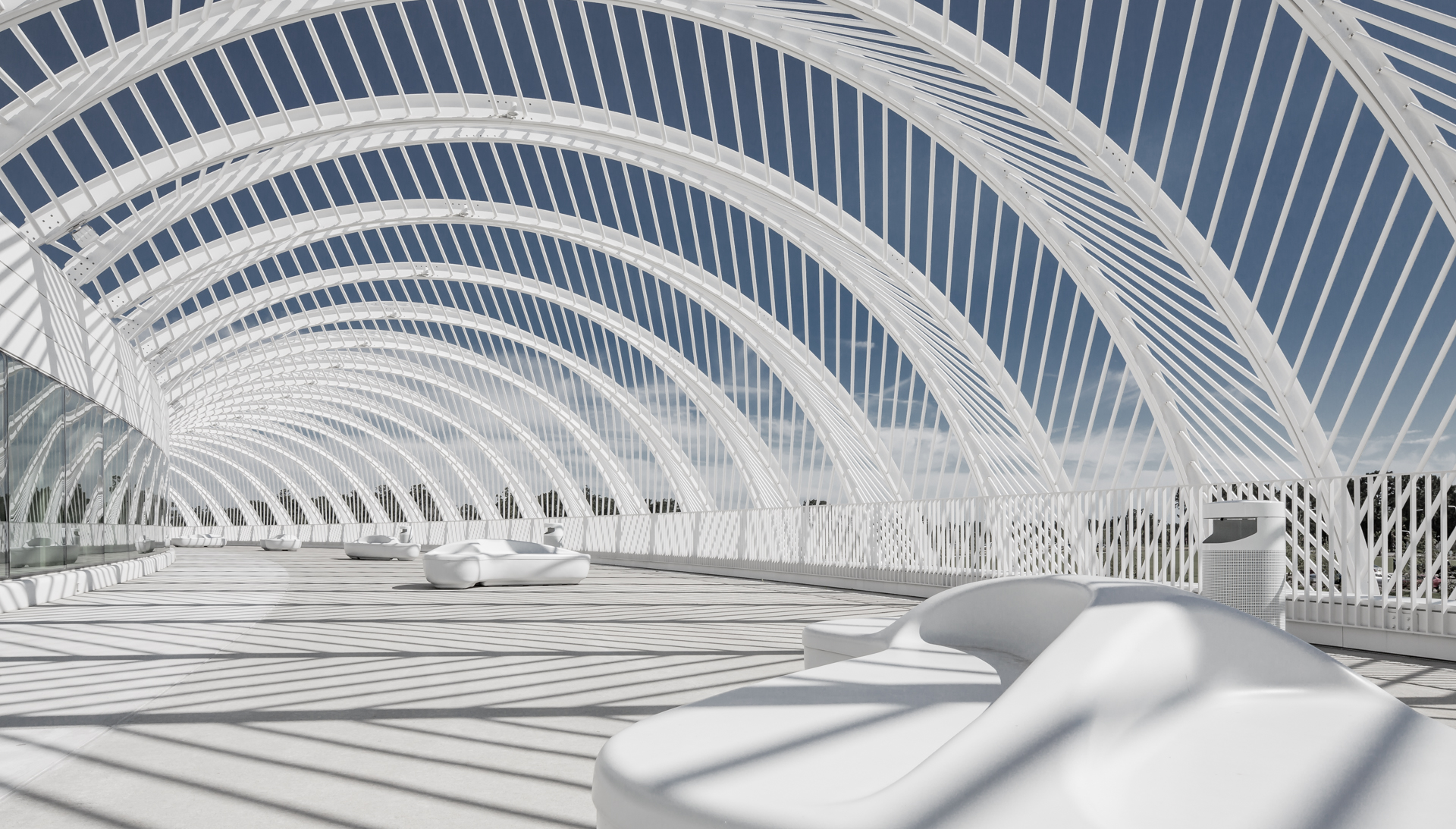

Designed at the intersection of engineering and architecture, this project creates a continuous canopy around the structure. Calatrava’s first building at Florida Polytechnic University, it was also named best in steel construction by AISC. The 160,000-square-foot (14,865-square-meter) IST Building opened as part of an institution hoping to give “physical representation to man’s highest aspirations.” The campus was being developed with the IST as its starting point.

Designed at the intersection of engineering and architecture, this project creates a continuous canopy around the structure. Calatrava’s first building at Florida Polytechnic University, it was also named best in steel construction by AISC. The 160,000-square-foot (14,865-square-meter) IST Building opened as part of an institution hoping to give “physical representation to man’s highest aspirations.” The campus was being developed with the IST as its starting point.

Calatrava stated that the “building will be an iconic symbol of the university; visible from Interstate 4 and Polk Parkway, as well as from the campus entry, which is located south of the central lake.” For the masterplan, an elliptical vehicular ring road, lined by tall palms, segregates vehicular traffic from the core of the campus. Administrative, academic, residential and other support facilities are placed within a grid around the central lake and complete the campus core.

Florida International University School of International and Public Affairs

By Arquitectonica, Miami, FL, United States

Arquitectonica’s approach at Florida International University was to create a mixed-use building that brings people together. The 57,085-square-foot (5,300-square-meter) structure includes classroom, office and auditorium programming on the edge of a lake on the university campus. Formally, the exterior walls of the five-story post tension concrete building are of sand-blasted precast concrete, and the structure also includes an extensive green roof.

Arquitectonica’s approach at Florida International University was to create a mixed-use building that brings people together. The 57,085-square-foot (5,300-square-meter) structure includes classroom, office and auditorium programming on the edge of a lake on the university campus. Formally, the exterior walls of the five-story post tension concrete building are of sand-blasted precast concrete, and the structure also includes an extensive green roof.

The auditorium acts as a focal point of the building. Its presence and function are evident from the exterior, as the large angular cantilevered form projects upward and outward from the lobby. The angles of the auditorium’s exterior follow the lines of the seating inside. The five-story tower opposite the auditorium has two large classrooms at the ground floor, with terrace access. Above are classrooms of various sizes, graduate study suites and language labs.

Perez Art Museum Miami

By ArquitectonicaGEO and Herzog & de Meuron, Miami, FL, United States

The PAMM building was designed by Herzog & de Meuron to express the raw material of concrete in its many forms. Due to its proximity to the water, the museum was lifted off the ground for the art to be placed above storm surge level. The team then used the space underneath the building for open-air parking, exposed to light and fresh air that can also handle storm-water runoff.

The PAMM building was designed by Herzog & de Meuron to express the raw material of concrete in its many forms. Due to its proximity to the water, the museum was lifted off the ground for the art to be placed above storm surge level. The team then used the space underneath the building for open-air parking, exposed to light and fresh air that can also handle storm-water runoff.

In contrast, the native plants been chosen by ArquitectonicaGEO display the raw materials of the landscape as complement and contrast to the geometric architecture of the building. The original project concept of formal hanging gardens was expanded to include the use of native plant material, in conjunction with systems to capture rain water. Rather than being an isolated “jewel box” for art lovers and specialists, the museum provides comfortable public space.

Mori Hosseini Student Union | Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

By ikon.5 architects, Daytona Beach, FL, United States

The student union building at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is an expression of its mission to teach the science, practice and business of aviation and aerospace. Located at the front door to the campus, the building’s gently soaring form expressing flight was designed to form an iconic identity for the University and embody the student values of fearlessness, adventure and discovery.

The student union building at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is an expression of its mission to teach the science, practice and business of aviation and aerospace. Located at the front door to the campus, the building’s gently soaring form expressing flight was designed to form an iconic identity for the University and embody the student values of fearlessness, adventure and discovery.

Internally, the 177,000-square-foot (16,445-square-meter) student union building is an aeronautical athenaeum combining social learning spaces, events, dining and the university library. A soaring, triple height commons anchors and integrates the collaborative social and learning interiors. Wrapping this space and open to it are lounges, dining venues, group study rooms, clubs and organizations, career services and the university library as well as an event center, creating a “city within a city.”

The Center for Asian Art at the Ringling Museum of Art

By Machado Silvetti, Sarasota, FL, United States

This iconic structure is a renovation and addition to a historic museum at Florida State University Sarasota. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art features both a permanent collection and temporary exhibition galleries. Now governed by Florida State University, the Museum establishes the Ringling Estate as one of the largest museum-university complexes in the United States. The Asian Art Study Center is an addition and ‘gut renovation’ and to the West Wing galleries on the southwest corner of the Museum complex.

This iconic structure is a renovation and addition to a historic museum at Florida State University Sarasota. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art features both a permanent collection and temporary exhibition galleries. Now governed by Florida State University, the Museum establishes the Ringling Estate as one of the largest museum-university complexes in the United States. The Asian Art Study Center is an addition and ‘gut renovation’ and to the West Wing galleries on the southwest corner of the Museum complex.

Connecting and making its own statement, the renovation converts approximately 18,000 square-feet (1,675-square-meter) of existing gallery space from temporary exhibition space to permanent galleries for the museum’s growing Asian collection. A 7,500 square-foot (695-square-foot) addition houses new gallery space and a multi-purpose lecture hall. The addition’s façade is composed of deep-green, glazed terra cotta tiles that address the client’s requirement of a new monumental entrance.

Brillhart House

By Brillhart Architecture, Miami, FL, United States

Designed for the architects themselves, this elevated, 1,500-square-foot (140-square-meter) house provides a tropical refuge in the heart of Downtown Miami. The house includes 100 feet of uninterrupted glass spanning the full length of both the front and rear façades, with four sets of sliding glass doors that allow the house to be entirely open when desired. Also included is 800 square feet (75 square meters) of outdoor living space, with front and back porches and exterior shuttered doors for added privacy and protection against the elements.

Designed for the architects themselves, this elevated, 1,500-square-foot (140-square-meter) house provides a tropical refuge in the heart of Downtown Miami. The house includes 100 feet of uninterrupted glass spanning the full length of both the front and rear façades, with four sets of sliding glass doors that allow the house to be entirely open when desired. Also included is 800 square feet (75 square meters) of outdoor living space, with front and back porches and exterior shuttered doors for added privacy and protection against the elements.

As Brillhart outlines, each design decision was organized around four questions: what’s necessary; how can they minimize impact on the earth; how do they respect the neighborhood; and what can they really build? Some answers came from the Dog Trot style house, which has been a dominant image representing Florida Cracker architecture for over a century. The glass pavilion typology and principles of Tropical Modernism also offered direction.

Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science

By Grimshaw Architects, Miami, FL, United States

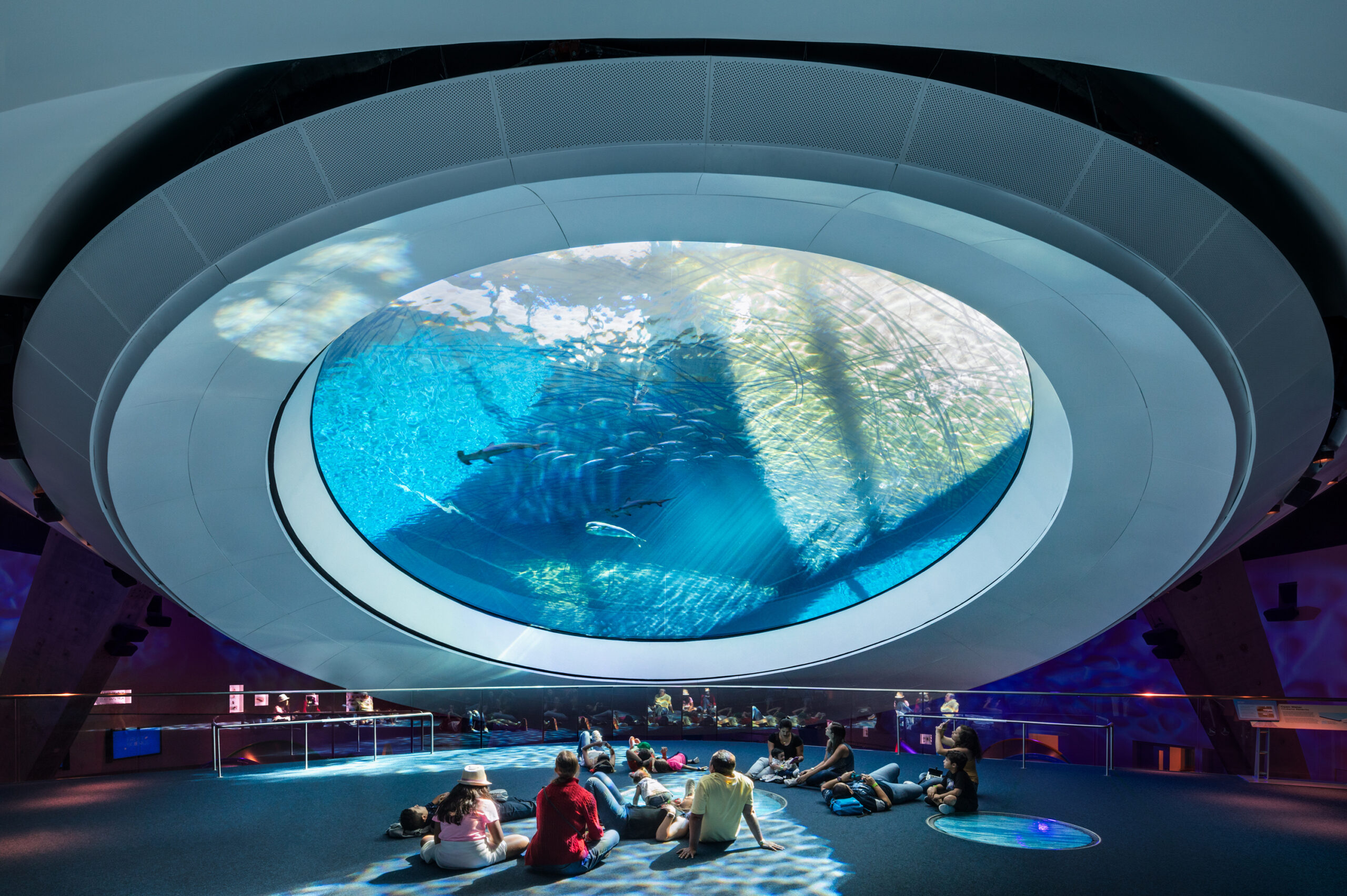

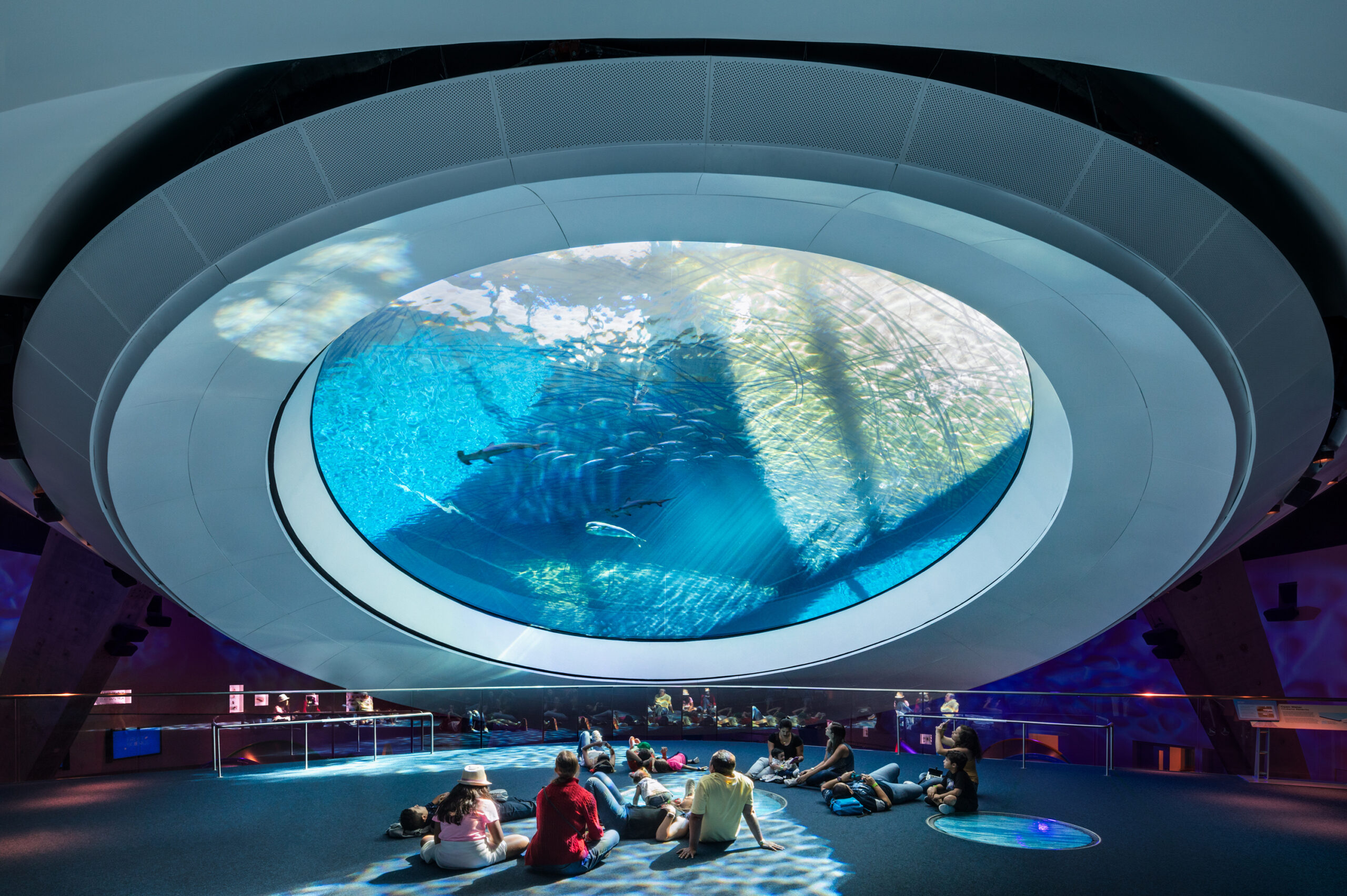

Grimshaw’s 250,000-square-foot (23,225-square-meter) facility brings together an aquarium, planetarium and science museum onto one campus in downtown Miami’s Museum Park. Taking advantage of the city’s sunshine, ocean breezes from nearby Biscayne Bay and views to a growing downtown skyline, the architecture of the museum furthers Miami-Dade County’s cultural offerings in a contemporary building. For the enclosure, the bar-shaped buildings of the North and West Wings are clad in a faceted, pixelated geometrical texture.

Grimshaw’s 250,000-square-foot (23,225-square-meter) facility brings together an aquarium, planetarium and science museum onto one campus in downtown Miami’s Museum Park. Taking advantage of the city’s sunshine, ocean breezes from nearby Biscayne Bay and views to a growing downtown skyline, the architecture of the museum furthers Miami-Dade County’s cultural offerings in a contemporary building. For the enclosure, the bar-shaped buildings of the North and West Wings are clad in a faceted, pixelated geometrical texture.

Grimshaw’s response to the project brief resulted in a complex of four buildings situated in an open-armed stance, inviting visitors to walk amongst them and opening up the building to the outdoors. An open-air atrium threads between the buildings connecting them to one another and creating a dynamic environment that directly connects the community to the experience of the outdoors and the city around them. The shapes of each individual building are dynamic and varied, sculpted to take advantage of filtered light and breezes.

The Dalí Museum

By HOK, Saint Petersburg, FL, United States

The Dalí Museum was designed to house the world’s most comprehensive collection of Salvador Dalí’s art outside of Spain. The design challenge was to create an affordable, iconic building symbolic of the Spanish painter’s work. The three-story museum is on a bayside site along St. Petersburg’s downtown waterfront. The dramatic envelope balances the exhibition and protection of the priceless masterpieces within a simple, powerful aesthetic.

The Dalí Museum was designed to house the world’s most comprehensive collection of Salvador Dalí’s art outside of Spain. The design challenge was to create an affordable, iconic building symbolic of the Spanish painter’s work. The three-story museum is on a bayside site along St. Petersburg’s downtown waterfront. The dramatic envelope balances the exhibition and protection of the priceless masterpieces within a simple, powerful aesthetic.

A “treasure box” shelters the 2,000-piece collection from potential Category 5 hurricane winds and storm surges. The design opens up the 18-inch-thick concrete walls with a free-form glass geodesic structure that intrigues visitors while bringing daylight and bay views into public spaces. The 75-foot-tall geodesic glass “Enigma” and 45-foot-tall “Igloo” are formed by 1,062 undulating faceted glass panes, with no two exactly alike.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

In the webinar, Ryan thoroughly explored the ins and outs of wall protection — from materials and installations to key decision-making processes, highlighting the main challenges architects often face.

In the webinar, Ryan thoroughly explored the ins and outs of wall protection — from materials and installations to key decision-making processes, highlighting the main challenges architects often face. The presentation offers deep insights, real-world examples and straightforward guidance, making it a must-watch for every architect and builder. Dive in to strengthen your designs and focus on lasting interiors.

The presentation offers deep insights, real-world examples and straightforward guidance, making it a must-watch for every architect and builder. Dive in to strengthen your designs and focus on lasting interiors.

Designed at the intersection of engineering and architecture, this project creates a continuous canopy around the structure. Calatrava’s first building at Florida Polytechnic University, it was also named best in steel construction by AISC. The 160,000-square-foot (14,865-square-meter) IST Building opened as part of an institution hoping to give “physical representation to man’s highest aspirations.” The campus was being developed with the IST as its starting point.

Designed at the intersection of engineering and architecture, this project creates a continuous canopy around the structure. Calatrava’s first building at Florida Polytechnic University, it was also named best in steel construction by AISC. The 160,000-square-foot (14,865-square-meter) IST Building opened as part of an institution hoping to give “physical representation to man’s highest aspirations.” The campus was being developed with the IST as its starting point.

Arquitectonica’s approach at Florida International University was to create a mixed-use building that brings people together. The 57,085-square-foot (5,300-square-meter) structure includes classroom, office and auditorium programming on the edge of a lake on the university campus. Formally, the exterior walls of the five-story post tension concrete building are of sand-blasted precast concrete, and the structure also includes an extensive green roof.

Arquitectonica’s approach at Florida International University was to create a mixed-use building that brings people together. The 57,085-square-foot (5,300-square-meter) structure includes classroom, office and auditorium programming on the edge of a lake on the university campus. Formally, the exterior walls of the five-story post tension concrete building are of sand-blasted precast concrete, and the structure also includes an extensive green roof.

The PAMM building was designed by Herzog & de Meuron to express the raw material of concrete in its many forms. Due to its proximity to the water, the museum was lifted off the ground for the art to be placed above storm surge level. The team then used the space underneath the building for open-air parking, exposed to light and fresh air that can also handle storm-water runoff.

The PAMM building was designed by Herzog & de Meuron to express the raw material of concrete in its many forms. Due to its proximity to the water, the museum was lifted off the ground for the art to be placed above storm surge level. The team then used the space underneath the building for open-air parking, exposed to light and fresh air that can also handle storm-water runoff.

The student union building at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is an expression of its mission to teach the science, practice and business of aviation and aerospace. Located at the front door to the campus, the building’s gently soaring form expressing flight was designed to form an iconic identity for the University and embody the student values of fearlessness, adventure and discovery.

The student union building at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is an expression of its mission to teach the science, practice and business of aviation and aerospace. Located at the front door to the campus, the building’s gently soaring form expressing flight was designed to form an iconic identity for the University and embody the student values of fearlessness, adventure and discovery.

This iconic structure is a renovation and addition to a historic museum at Florida State University Sarasota. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art features both a permanent collection and temporary exhibition galleries. Now governed by Florida State University, the Museum establishes the Ringling Estate as one of the largest museum-university complexes in the United States. The Asian Art Study Center is an addition and ‘gut renovation’ and to the West Wing galleries on the southwest corner of the Museum complex.

This iconic structure is a renovation and addition to a historic museum at Florida State University Sarasota. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art features both a permanent collection and temporary exhibition galleries. Now governed by Florida State University, the Museum establishes the Ringling Estate as one of the largest museum-university complexes in the United States. The Asian Art Study Center is an addition and ‘gut renovation’ and to the West Wing galleries on the southwest corner of the Museum complex.

Designed for the architects themselves, this elevated, 1,500-square-foot (140-square-meter) house provides a tropical refuge in the heart of Downtown Miami. The house includes 100 feet of uninterrupted glass spanning the full length of both the front and rear façades, with four sets of sliding glass doors that allow the house to be entirely open when desired. Also included is 800 square feet (75 square meters) of outdoor living space, with front and back porches and exterior shuttered doors for added privacy and protection against the elements.

Designed for the architects themselves, this elevated, 1,500-square-foot (140-square-meter) house provides a tropical refuge in the heart of Downtown Miami. The house includes 100 feet of uninterrupted glass spanning the full length of both the front and rear façades, with four sets of sliding glass doors that allow the house to be entirely open when desired. Also included is 800 square feet (75 square meters) of outdoor living space, with front and back porches and exterior shuttered doors for added privacy and protection against the elements.

Grimshaw’s 250,000-square-foot (23,225-square-meter) facility brings together an aquarium, planetarium and science museum onto one campus in downtown Miami’s Museum Park. Taking advantage of the city’s sunshine, ocean breezes from nearby Biscayne Bay and views to a growing downtown skyline, the architecture of the museum furthers Miami-Dade County’s cultural offerings in a contemporary building. For the enclosure, the bar-shaped buildings of the North and West Wings are clad in a faceted, pixelated geometrical texture.

Grimshaw’s 250,000-square-foot (23,225-square-meter) facility brings together an aquarium, planetarium and science museum onto one campus in downtown Miami’s Museum Park. Taking advantage of the city’s sunshine, ocean breezes from nearby Biscayne Bay and views to a growing downtown skyline, the architecture of the museum furthers Miami-Dade County’s cultural offerings in a contemporary building. For the enclosure, the bar-shaped buildings of the North and West Wings are clad in a faceted, pixelated geometrical texture.

The Dalí Museum was designed to house the world’s most comprehensive collection of Salvador Dalí’s art outside of Spain. The design challenge was to create an affordable, iconic building symbolic of the Spanish painter’s work. The three-story museum is on a bayside site along St. Petersburg’s downtown waterfront. The dramatic envelope balances the exhibition and protection of the priceless masterpieces within a simple, powerful aesthetic.

The Dalí Museum was designed to house the world’s most comprehensive collection of Salvador Dalí’s art outside of Spain. The design challenge was to create an affordable, iconic building symbolic of the Spanish painter’s work. The three-story museum is on a bayside site along St. Petersburg’s downtown waterfront. The dramatic envelope balances the exhibition and protection of the priceless masterpieces within a simple, powerful aesthetic.