A firm specializing in remodeling rethinks its approach to attic and roof insulation to lower embodied carbon.

By Rachel White

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put the world on notice: To avert catastrophic and irreversible climate change, we will have to hold global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. And to keep warming at this level, we must cut global emissions roughly in half by 2030 and get to zero by 2050.

Building Sector Contributions to Global Warming

The building sector is a huge part of the problem, accounting for roughly 40% of global annual emissions. And while our industry has made progress, we haven’t done nearly enough.

Along with the work of organizations such as the Carbon Leadership Forum and Architecture 2030, the IPCC report was a wake-up call about the time value of carbon. Larry Strain, a board member at the Carbon Leadership Forum, describes it this way: “Because emissions are cumulative and we have a limited amount of time to reduce them, carbon reductions now have more value than carbon reductions in the future [emphasis added].”

Carbon Reduction Strategies

Three strategies are critical to achieving meaningful near-term reductions in building sector emissions. First, we need to repurpose buildings rather than build new ones wherever possible. Second, we need to aggressively reduce the operating emissions of existing buildings. Third, we need to build with low embodied carbon materials and ideally with carbon-storing materials.

The first two strategies are firmly ensconced at Byggmeister. We don’t do new construction, we avoid additions, and we pursue operational emissions reductions whenever possible. However, until the last couple of years, we had not paid much attention to embodied carbon. We assumed that whatever carbon we emitted to renovate and retrofit homes would be balanced by operational savings over decades. But this assumption was flawed.

Embodied Carbon Emissions

So, we turned our attention to embodied emissions, focusing first on insulation. As remodeling contractors, we know that insulation is high leverage, especially because closed-cell spray foam—one of the highest embodied carbon insulation materials on the market—has long been a go-to insulation material for us. There are good reasons we have relied so heavily on closed-cell spray foam. It blocks air leaks in addition to reducing conductive heat loss; it’s vapor impermeable; and it’s highly versatile. But none of these is a good reason to maintain the status quo.

Deciding When to Use Foam

There are times when replacing spray foam with a carbon smarter material is a no-brainer. For example, installing cellulose in wood-framed walls is typically no more complex than insulating with spray foam, not to mention less expensive and less disruptive. And while the R-value of a cellulose-insulated wall is lower than the same wall insulated with closed-cell spray foam (unless the wall assembly is thickened), we believe this compromise is worth it. The reduced R-value has little impact on comfort and the carbon benefit more than makes up for it. Unlike spray foam, which emits a lot of carbon before, during, and immediately after installation ( especially true of closed-cell spray foam with high-embodied-carbon blowing agents), cellulose actually stores carbon.

There are other cases, though, such as with rubble foundation walls, when we feel spray foam is the only viable choice, other than not insulating at all. While we have entertained this possibility, we aren’t willing to give up remediating dank, damp basements, although we have begun to think about these as emissions that should be offset with more aggressive carbon-storing measures elsewhere.

Roof Insulation Challenges

Much of the time, though, the choice to eliminate or retain spray foam isn’t clear-cut. We encounter many roofs and attics where existing conditions, code requirements, and broader project goals make it challenging but not impossible to avoid spray foam.

If the attic is unconditioned, then the easiest, most cost-effective strategy is to air seal any penetrations along the attic floor and then re-insulate (in most cases, we would first remove existing insulation).

But this only works if there’s no mechanical equipment (and ideally no storage). If the attic is used for anything other than insulation, best practice is to bring the attic space indoors, either by insulating the underside of the roof sheathing with spray foam or by removing the roofing, insulating the topside of the roof sheathing with rigid foam and then re-roofing.

If the roof needs to be replaced, “outsulation” might initially seem viable. But I can count on one hand the times we have actually done it. More often than not, it’s doomed by cost or adverse architectural consequences. This is why spray foam has long been our go-to approach for unconditioned attics with HVAC equipment.

New Approaches for Lower Carbon

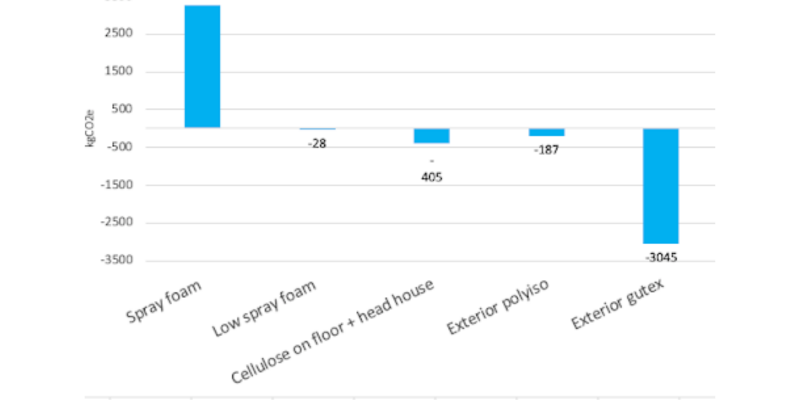

At least it was until we realized just how carbon-intensive it is. We came to this realization by comparing the embodied emissions of spray foam against four alternatives. We based these comparisons on a simple gable-roof form. The four alternatives we looked at were:

* A low-foam approach of building down the rafter bays, insulating with closed-cell foam for condensation control, followed by cellulose behind a smart membrane.

* A no-foam approach where the air and thermal boundary remains at the attic floor. We install the air handler in a conditioned “head house” and bury the ductwork in cellulose.

* A common outsulation approach with cellulose in the rafter bays plus exterior polyisocyanurate board foam.

* A newer, no-foam outsulation approach with cellulose in the rafter bays plus exterior wood fiber board. All of these approaches, including exterior polyisocyanurate, are either carbon neutral or carbon storing from the outset. Only spray foam starts off in carbon debt.

This chart shows the embodied carbon of several options for insulating the attic floor or the roof. Chart courtesy Byggmeister.

What we call the “low foam” approach includes 3 inches of closed-cell spray foam on the underside of the roof deck plus 8 inches of cellulose and a membrane to control moisture. Illustration courtesy Byggmeister.

And this debt is not small. Our modeling suggests this particular measure would take 14 years of operational carbon savings to break even. Even if our model isn’t exact, it’s close enough to know that spray foam should not be our default approach if there are viable, lower emitting alternatives.

In Two Carbon Smart Ideas for the Attic, we walk through the no-foam, head house approach in detail. We also describe our efforts to develop a carbon-smart approach to another common attic/roof condition: poorly insulated, finished slopes. When such slopes are topped by a “micro attic,” we are experimenting with dense-packing the slopes, installing loose-fill cellulose along the floor of the micro-attic, and adding a ridge vent.

We Must Take Risks

Both of these approaches seemed impractical when we first took them on. Both present some level of risk. Because of code constraints, the second one may not be broadly replicable even if we can demonstrate that the risk is manageable. But if we are going to cut global carbon emissions in half by 2030 and get to zero by 2050, we’ll have to take some risks and pursue approaches that aren’t (yet) standard practice. By sharing our story, we hope to inspire more of our colleagues to join in this effort.

Rachel White is the CEO of Byggmeister, a design-build remodeling firm in Newton, Mass. This article was first published in Green Building Advisor.