Al-Qatt Al-Asiri: Inside the Homes of Saudi Arabia’s ‘Hanging Villages’

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

If you walk in the heart of ‘Asir province in southwestern Saudi Arabia, you’ll soon notice how unique this remote region is. Once part of the ancient South Arabian civilization, the Asir province played a key role in historical incense trade routes due to its fertile lands and rich terrain. Its strategic location made it a vital commerce and cultural exchange hub between Yemen, the Arabian Peninsula and beyond.

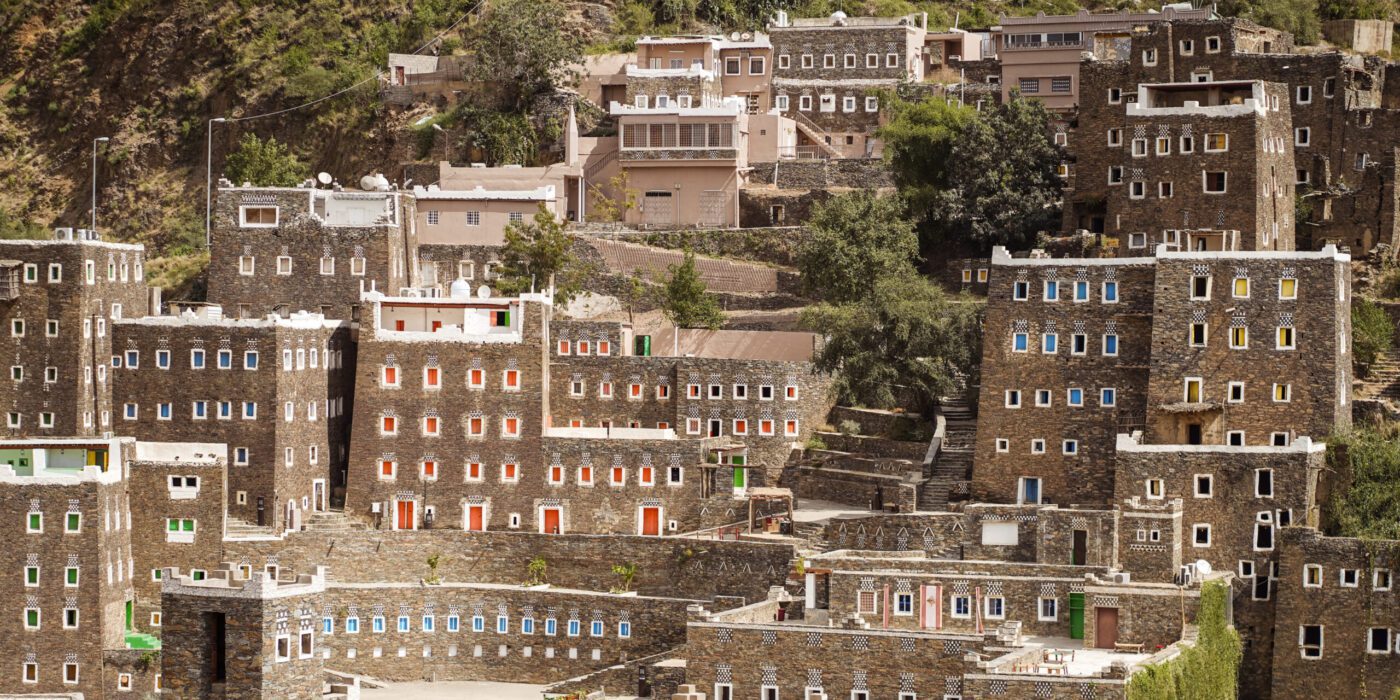

Until the late 20th century, ‘Asir was home to autonomous tribes residing in “hanging villages” that dotted the cliffsides of the rugged highlands. Some settlements were only accessible by precarious rope ladders. For years, the challenging terrain, geographic isolation and scarce resources fostered a distinctive, self-reliant culture among these communities that was largely unknown to the outside world.

In recent years, with a huge push from the Saudi Arabian government to increase tourism, interest in the area’s culture and heritage has grown, most notably in the astonishing architecture of the ‘Asir region.

Panorama of beautiful historical houses in Rijal Almaa heritage village in Saudi Arabia. Photograph by Juan Alberto Ruiz

Tulul are traditional mud-brick homes that stand out for their practicality and ingenious integration into the mountainous landscape. Constructed using locally sourced materials, these homes feature thick earthen walls of clay, straw and water, offering natural insulation against the region’s extreme temperature fluctuations. Typically, tulul homes have flat roofs and are spread across multiple floors to maximize vertical space.

The exterior of tulul buildings are usually a natural color from the earth that allows them to blend into the surrounding cliffside. However, in some regions, they are painted with white lime wash, creating a beautiful contrast against the green, mountainous backdrop. Rendering the facades in this way acts as a practical solution to reduce heat gain in an area with fluctuating temperature extremes. Windows in a tulul are small and strategically placed to minimize heat intake and simultaneously maximize ventilation.

Heritage village of Rijal Almaa in Southern Saudi Arabia. Photograph by hari.ksa

While the façades of these buildings are undoubtedly impressive it is the inside of the tulul that has become a source of fascination for the outside world. As the men built the clusters of skyscraper-like homes that dot the cliffs, the ingenuity of women enlivened the interior. On the stairways and entrances, or the majlis (a welcoming space), tulul are painted with colorful, geometric designs known as Al-Qatt Al-Asiri.

Al-Qatt (from the Arabic word for “to write” and pronounced “gath”) Al-Asiri is a creative process characterized by bold, rich, statement murals that are designed as abstract, freehand geometric symbols and patterns. The technique is passed down from one generation of women to the next and involves creating intricate shapes like triangles, squares, diamonds and dots using black crosslines set against pure white gypsum walls. It is a process that is spontaneous and unplanned. The shapes — reminiscent of designs that can be found across Indian, North African and Latin American cultures — are then colored in. The women of Asir turned natural materials — carbon from candles for black, iron-rich Al Meshgah stones for red and limestone for white — into a palette of pigments that were bound with adhesives from local trees to create rich, vibrant hues.

Abha, Saudi Arabia – 07 Mar 2020: The museum in Abha, Saudi Arabia. Photograph by Sergey.

The shapes and patterns of the Al-Qatt Al-Asiri murals are not random. At its core, Al-Qatt Al-Asiri is a visual language that the women of ‘Asir use to document their values, beliefs and connection to nature. Each of the symbols is a message about community, spirituality and the natural world. Often, they symbolize people, religion and elements of the environment, such as trees, feathers, corn and mountains. Each part, or layer, represents something specific. For instance, the repeated use of triangles in Al-Qatt Al-Asiri artwork symbolizes the family unit, and concentric squares symbolize the completion of the Quran.

Decorative geometric repeating pattern inspired by Al-Qatt Al-Asiri traditional paintings. Image by Richard Laschon

The motifs have names inspired by the landscape and life of ‘Asir: Balsana is a mesh-like design with dots in the center that signifies wheat bran, a staple crop in the region, while Al Mahareeb (plural of Mehrab) is the half-circle used to denote the direction of Mecca. Alkaf are horizontal lines painted at the bottom of a wall, and women use their fingers to measure the width of the design. Al Batra — with its wide vertical stripes and white spaces — are meant to break the repetitive designs and draw the viewers’ attention to a specific section of the mural. The patterns are intricate, beautiful and enchanting.

Most of all, Al-Qatt Al-Asiri has a crucial role in fostering a sense of community and collective identity among the women of ‘Asir. The practice of this art form is inherently communal, often involving groups of women coming together to paint, share stories and pass on techniques to younger generations. This helps to strengthen social bonds and reinforces a secure cultural identity while providing space for women to express themselves creatively and contribute to the preservation of their cultural heritage.

Rijal Almaa world heritage site in Asir region, Saudi Arabia. Photograph by hyserb.

In a region historically isolated and challenged by its rugged terrain, Al-Qatt Al-Asiri flourished under female creativity. Today, it is becoming more widely adopted by artists from the region who want to protect its existence. Through their art form, women have been able to carve out a space for themselves as artists and guardians of their culture, gaining respect and recognition within their communities and now internationally.

In 2017, Al-Qatt Al-Asiri garnered global attention when the art form was added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. This milestone underscores its profound cultural significance and honors its custodians, the women of ‘Asir.

Al-Qatt Al-Asiri designs can be seen all over the ‘Asir region in architecture, pottery, fireplaces, carvings and fabrics. However, Rijal Almaa, a Museum and Al Khalaf Archaeological Village, shows the greatest examples of this beautiful art form. Featuring over sixty tulul buildings, the well-preserved site gives an unparalleled glimpse into the local heritage with its extensive display of Al-Qatt Al-Asiri.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.