Questioning the Meaning of Urban Campus: The Sciences Po Campus by Moreau Kusunoki

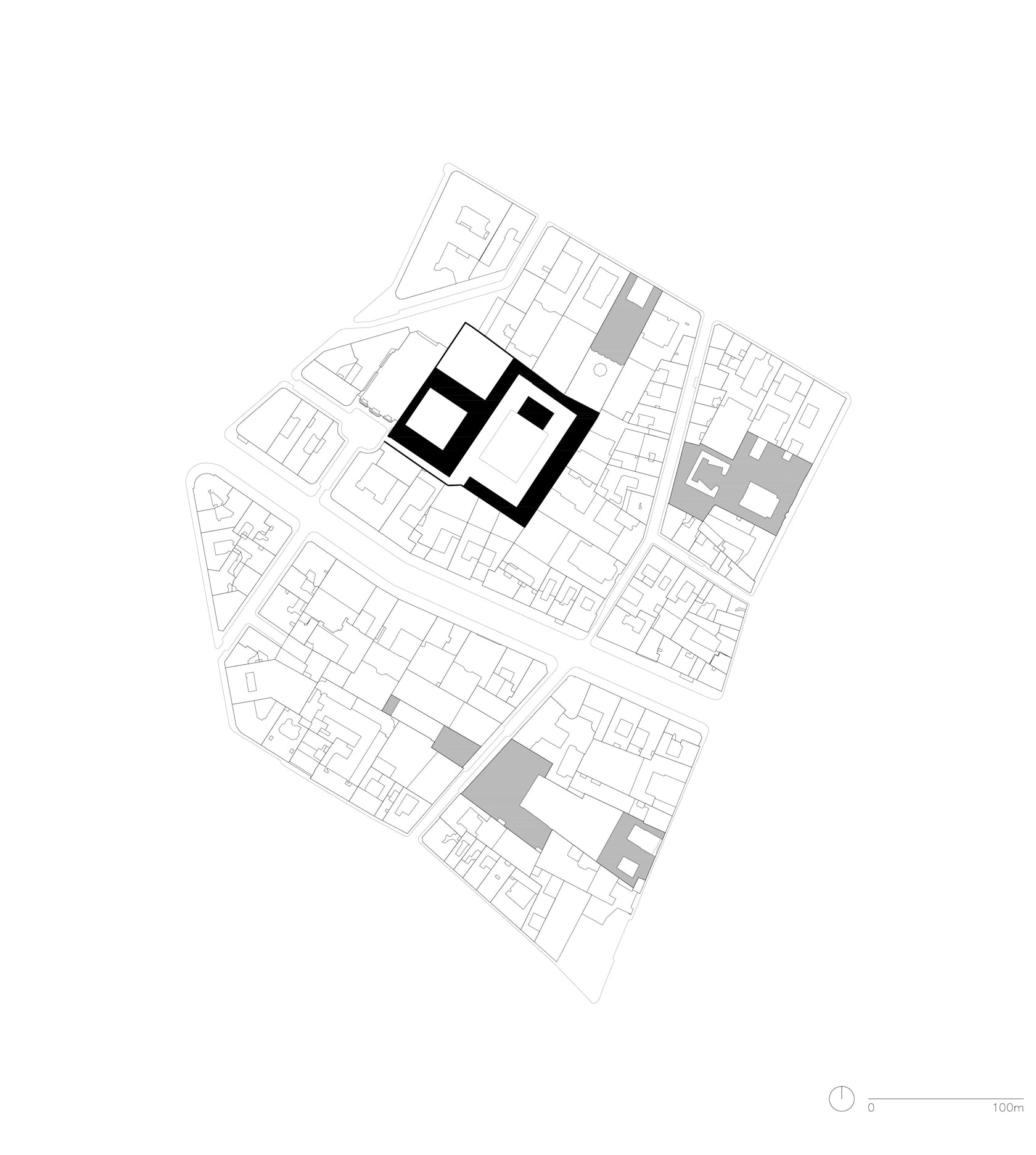

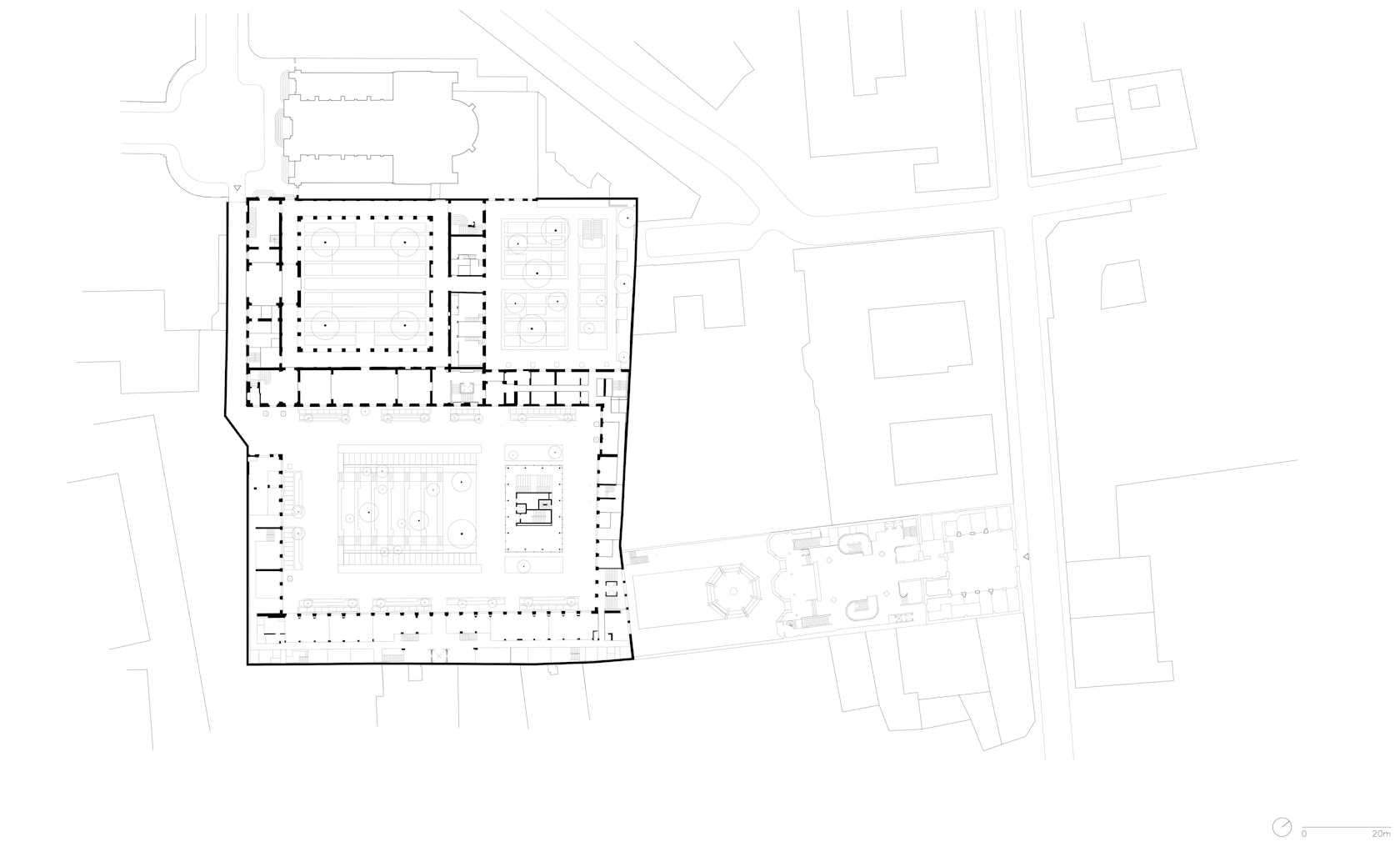

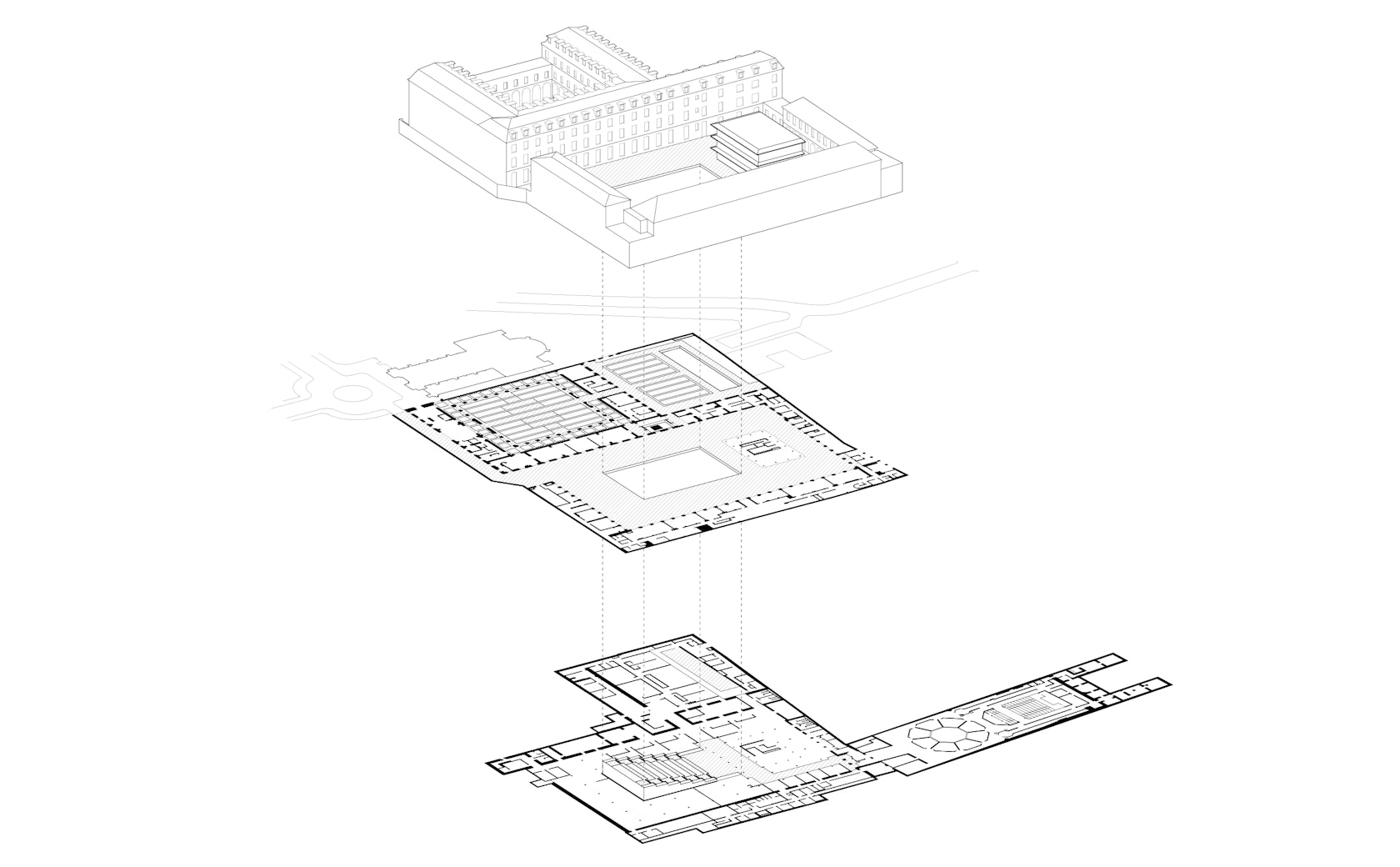

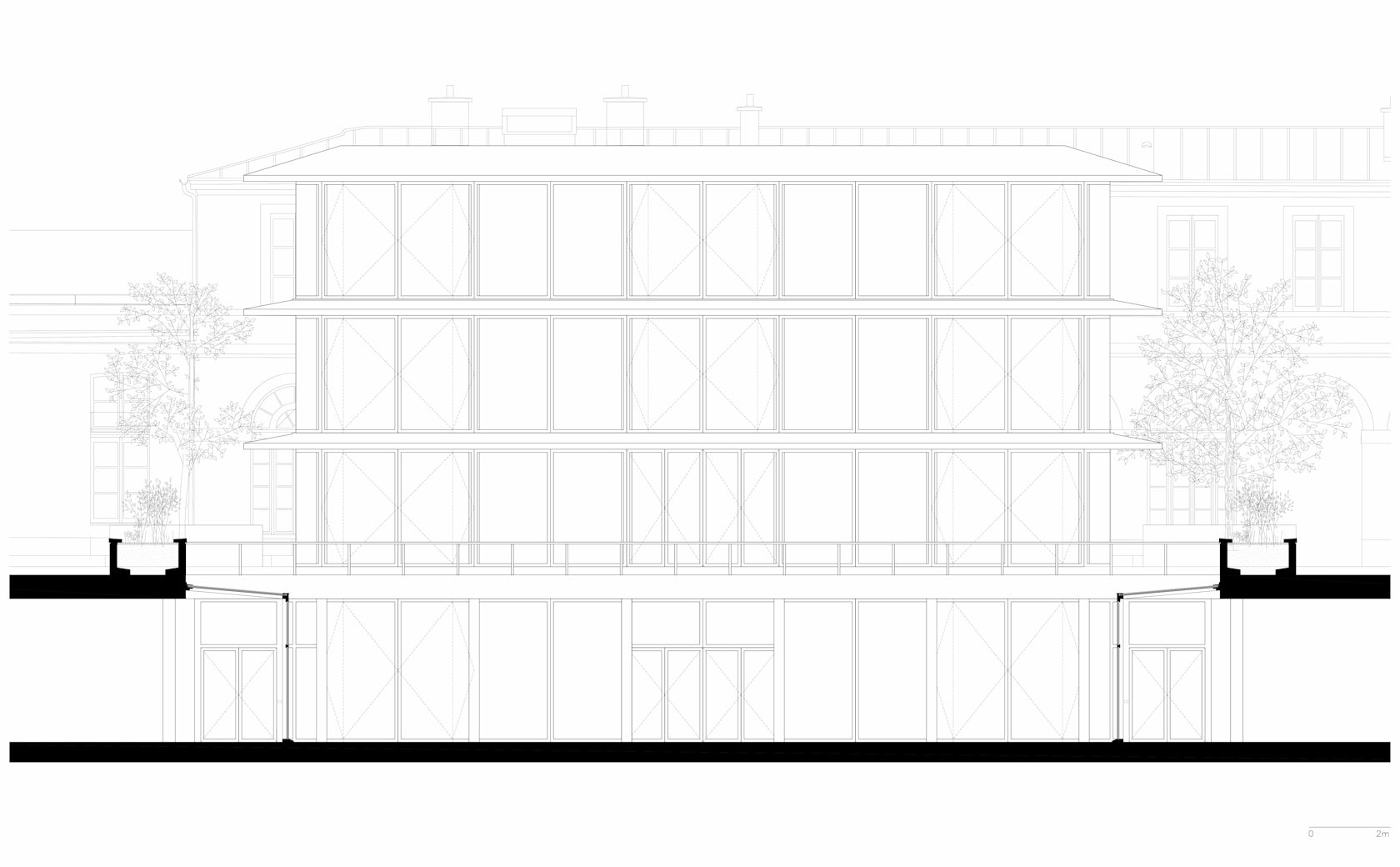

Sciences Po – The new campus of Sciences Po questions the meaning of being located in a city, as opposed to the proliferation of new campuses that have been built in a suburban environment. As an urban campus enmeshed within the fabric of the city, the centerpiece of Moreau Kusunoki’s design is the central pavilion located in the main courtyard. Inspired by the concept of a ‘pavillon de thé’, the glass-paneled structure represents both a refuge and transparency by the unique continuity of its innovative pivoting façade, seamlessly transitioning from inside to outside. This new technology has made it possible to create a safe and secure facility that simultaneously acts as a symbol of openness to the world.

Architizer chatted with Hiroko Kusunoki and Nicolas Moreau, co-founders of Moreau Kusunoki, to learn more about this project.

Architizer: What inspired the initial concept for your design?

Hiroko Kusunoki and Nicolas Moreau: The project was inspired by a historical understanding of the site and a reaction to its physical givens, as inherited and as found. Nested within the innermost courtyard of an old convent turned campus, the project formally establishes itself as a new focal point, all while nurturing a calm and respectful conversation with its limestone surroundings.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

This project won in the 10th Annual A+Awards! What do you believe are the standout components that made your project win?

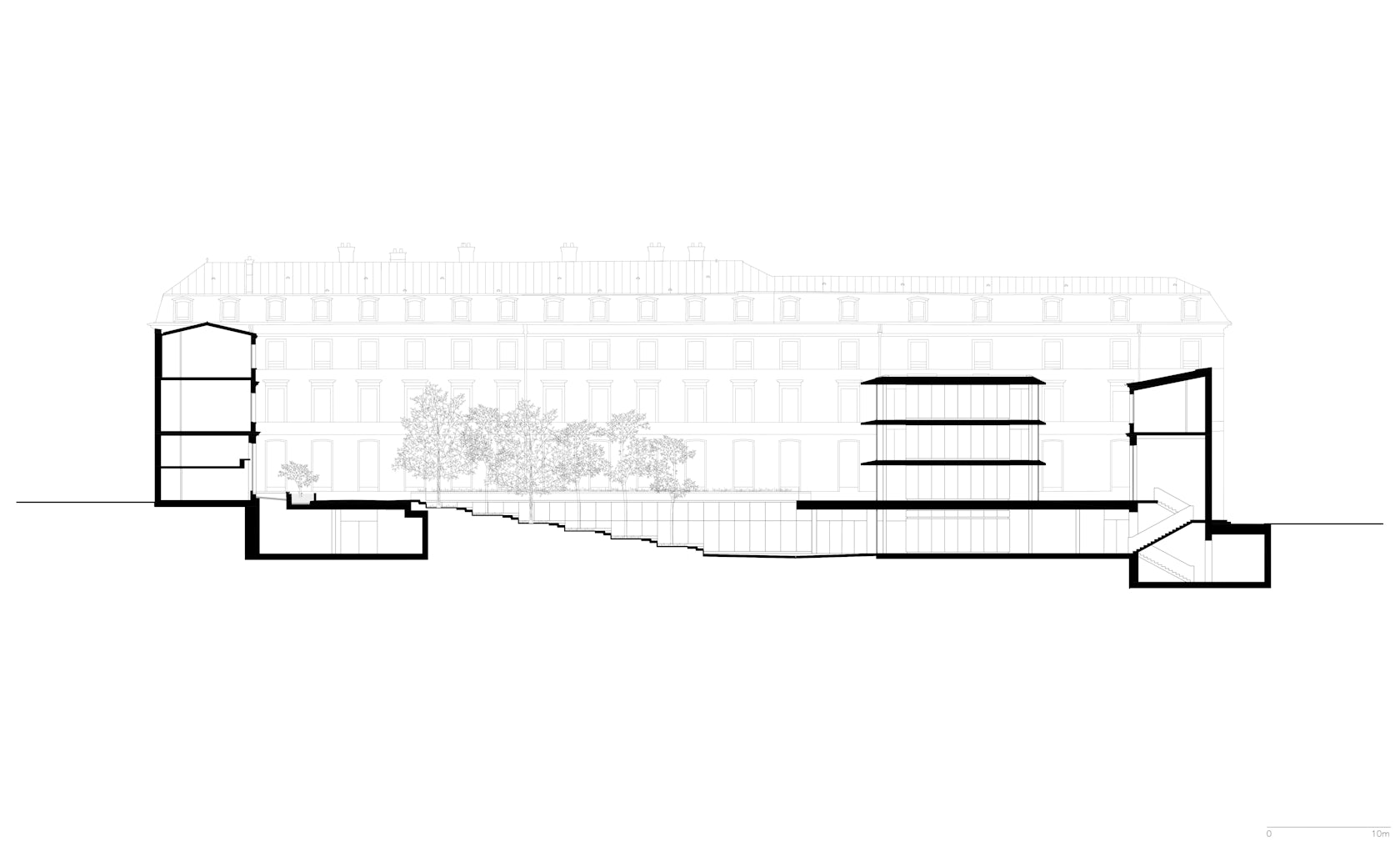

The pavilion offers the unique experience of becoming synchronized with exterior spaces when all the large pivoting doors are opened. It removes the interiority of the space and becomes a pure stage, exposed to the wind, light and sounds of the city.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

What was the greatest design challenge you faced during the project, and how did you navigate it?

The pavilion is designed based on the broad palette of grays reflected through different materialities: steel, concrete, paint, glass, the Paris sky. The uniformity of the tone of gray offers abstraction and silence. These subtle nuances create a form of micro visual vibration within the space, providing an extra layer of quiet, sensorial appreciation when approached closely or touched.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

How did the context of your project — environmental, social or cultural — influence your design?

The fluidity of people coming in and out of the location, the levelling of human interaction, are the real opportunities provided by this new campus. As opposed to simply continuing the tradition and history of Sciences Po, people are encouraged to reimagine the school’s image.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

How important was sustainability as a design criteria as you worked on this project?

Sustainability is a fundamental driver of this project. In spite of a fully glazed façade, the design succeeds at instilling a solid level of comfort by providing the option of using natural ventilation. The canopies play a fundamental role in protection from solar radiation while also conferring the architectural identity of the pavilion.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

How have your clients responded to the finished project?

The pavilion became the “showcase” of the new Sciences Po campus, inspiring the most important donors to the project to install their offices in the pavilion.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

How do you believe this project represents you or your firm as a whole?

This project demonstrates our commitment to the integrity of our architectural concept, which is defined by readability, simplicity, as well as duality.

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

© MOREAU KUSUNOKI

How do you imagine this project influencing your work in the future?

Every project provides an opportunity to try things out, to find prototypes. We will continue collaborating with builders to develop unique façade systems that allow for improved interaction and continuity between interior and exterior spaces.

Team Members

Architects : Moreau Kusunoki, Wilmotte & Associates (coordination), Pierre Bortolussi (heritage). Partners: Groupe Sogelym Dixence (promoter), Franck Boutté Consultants (sustainable engineering), Mugo (landscaping), Barbanel (MEP), TERRELL Group (façade engineering), SASAKI (strategy and urban planning), CORELO (project management). Client: La Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques (FNSP)

Sciences Po Gallery

Krishna P. Singh Center for Nanotechnology by WEISS/MANFREDI, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Krishna P. Singh Center for Nanotechnology by WEISS/MANFREDI, Philadelphia, PA, United States

National Nanotechnology Park by Arch International Pvt Ltd., Homagama, Sri Lanka

National Nanotechnology Park by Arch International Pvt Ltd., Homagama, Sri Lanka

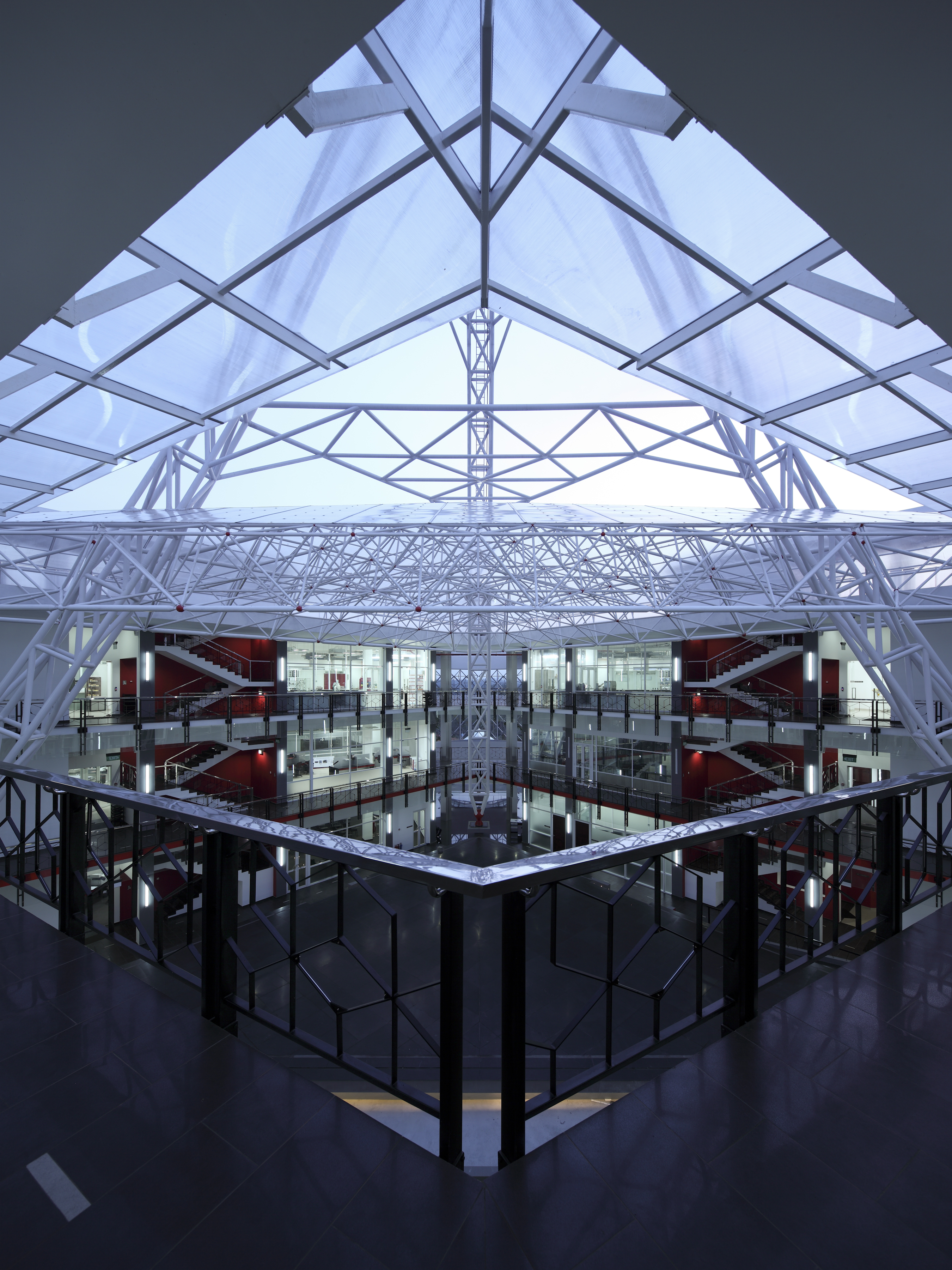

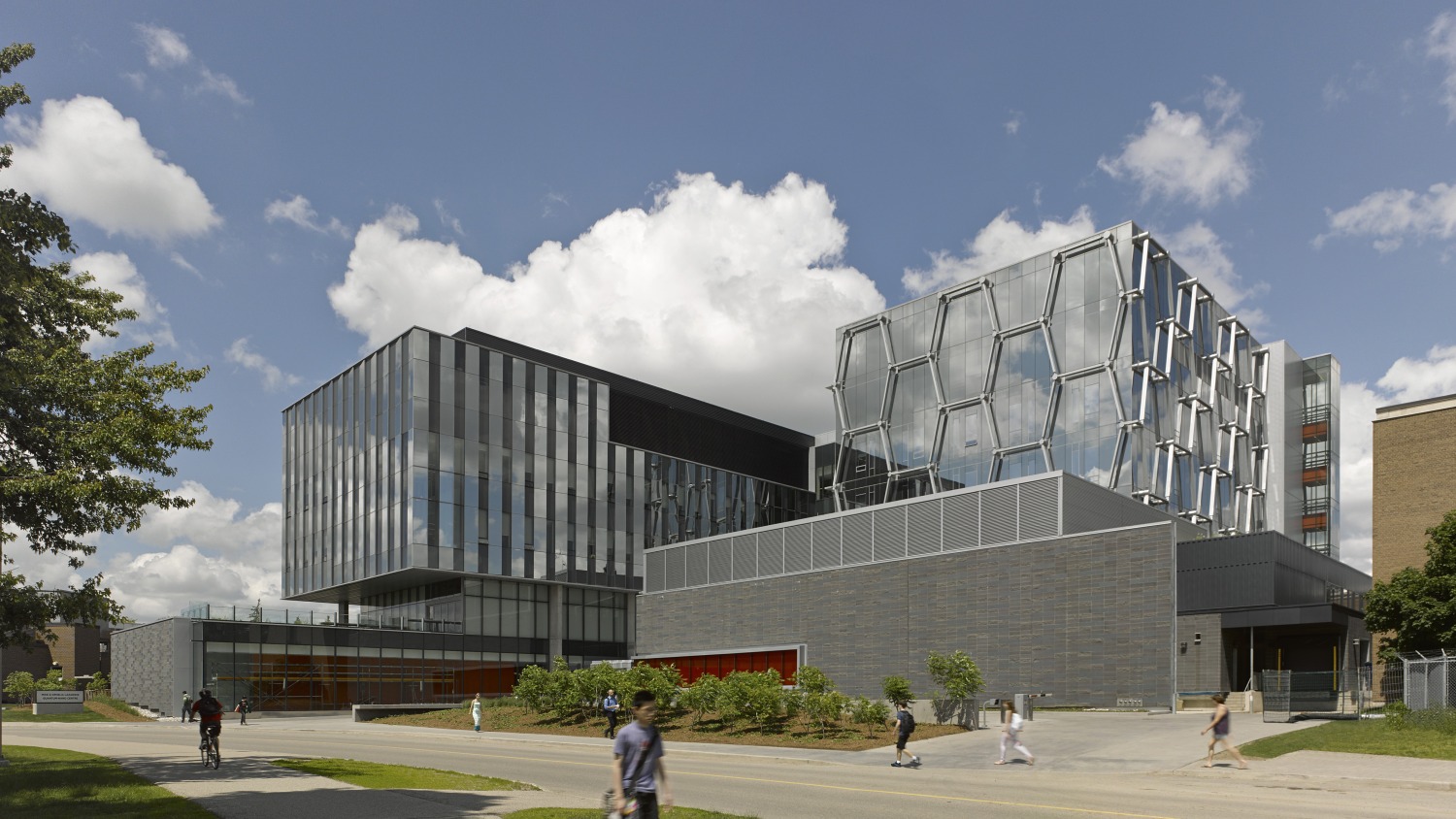

Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano Centre by KPMB Architects, Waterloo, Canada

Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano Centre by KPMB Architects, Waterloo, Canada

New Center for Manufacturing Innovation by Brooks + Scarpa Architects, Monterrey, Mexico

New Center for Manufacturing Innovation by Brooks + Scarpa Architects, Monterrey, Mexico

Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation

Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation

La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science by Lyons, Melbourne, Australia

La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science by Lyons, Melbourne, Australia