Ubiquitous Energy aims to make solar windows the global standard

US company Ubiquitous Energy has invented a thin coating that turns windows into transparent solar panels, providing other ways to harvest renewable energy in buildings beyond rooftop panels.

Ubiquitous Energy describes its technology as being the only transparent photovoltaic glass coating that is “visibly indistinguishable” from traditional windows.

Any surface could become a solar panel

The company was founded in 2011 by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Michigan State University (MSU), who engineered a transparent solar panel by allowing the visible spectrum of light to pass through and only absorbing ultraviolet and near-infrared light to convert to electricity.

Standard solar panels look black because they absorb the full spectrum of light, and because of their appearance, their deployment has been typically limited to roofs, walls and large rural solar farms.

With Ubiquitous Energy’s coating, which it calls UE Power, potentially any surface can be turned into a photovoltaic panel.

“The mission is to turn all these everyday surfaces around us into essentially renewable energy generators,” Ubiquitous Energy VP of Strategy Veeral Hardev told Dezeen.

“Windows is where we’re focused first, but beyond that, think about vehicles, transportation in general, portable consumer electronics devices, sustainable farming like greenhouses – these are all things that see sunlight to some degree,” he continued.

“Why not improve them so that they can actually generate renewable energy themselves without changing their appearance?”

Hardev said the company’s modelling shows that with broad adoption of the technology to the point that in 30 years the coating is as standard as low-emissivity (or low-E) coatings on windows are now, it could offset 10 per cent of global carbon emissions.

All components are completely transparent

The solar window works in the same way as any other solar panel. It contains cells of a semiconductor material that create an electric charge in response to sunlight.

Wiring hidden in the window frames connects it to the building’s energy management system to direct power to where it’s needed in the building or to store it in a battery.

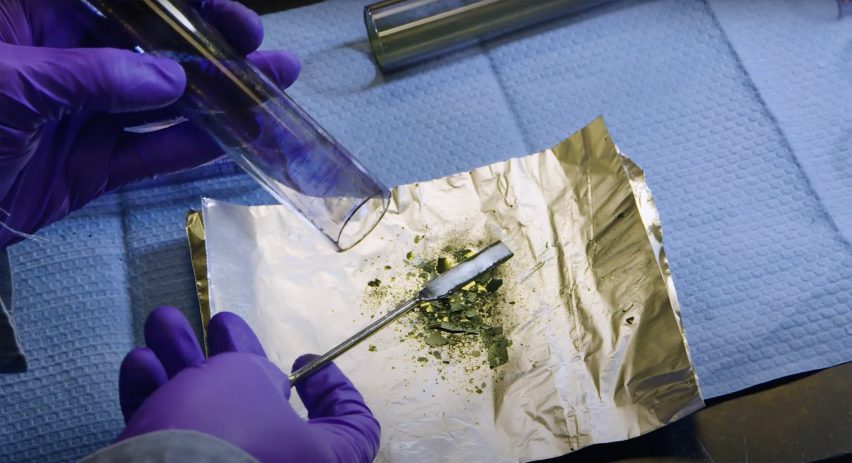

The innovation with Ubiquitous Energy is that all of its materials are transparent to the human eye, including the semiconducting compounds, which take the form of light-absorbing dyes.

To achieve its thinness – the coating is about one micrometre thick, or about 80 to 100 times thinner than a human hair – it is made with nanomaterials, similar to those used in display technologies.

The semiconductor layers are deposited onto glass using vacuum physical vapor deposition (PVD) – a standard coating process using in the window industry – and Ubiquitous Energy plans to license its technology to existing glass manufacturers so that they can incorporate it into their product offerings.

Transparent panels only half as efficient

Ubiquitous Energy estimates the windows would provide about 30 per cent of a building’s electricity needs, depending on factors such as geographical location, elevation and tree cover, and imagine them being used in conjunction with rooftop solar panels to reduce the building’s reliance on the electrical grid.

Because some light is allowed to pass through, the transparent solar panel is only about half as powerful as a typical rooftop solar panel of the same size. But Hardev claims their potential scale of deployment compensates for this loss of efficiency.

“A few years ago, we reported the highest-ever performance for a transparent solar device, with near 10 per cent efficiency,” said Hardev. “Although there are options that are 20 per cent efficient today, we’re making this conscious trade-off of being transparent so we can put it in places where you can’t put traditional solar panels.”

Cities would theoretically be able to produce substantial amounts of solar power locally without changing in appearance, reducing the need for land for large solar power plants.

First factory to open in 2024

Applied in other ways, the coating could be used to make mobile phones that don’t need to be recharged, more energy-efficient cars and self-powering greenhouses, Hardev says.

“We’re first starting with windows because we think that is the area that is going to have the biggest overall impact,” said Hardev, citing the statistic that nearly 40 per cent of total global energy-related CO2 emissions come from buildings.

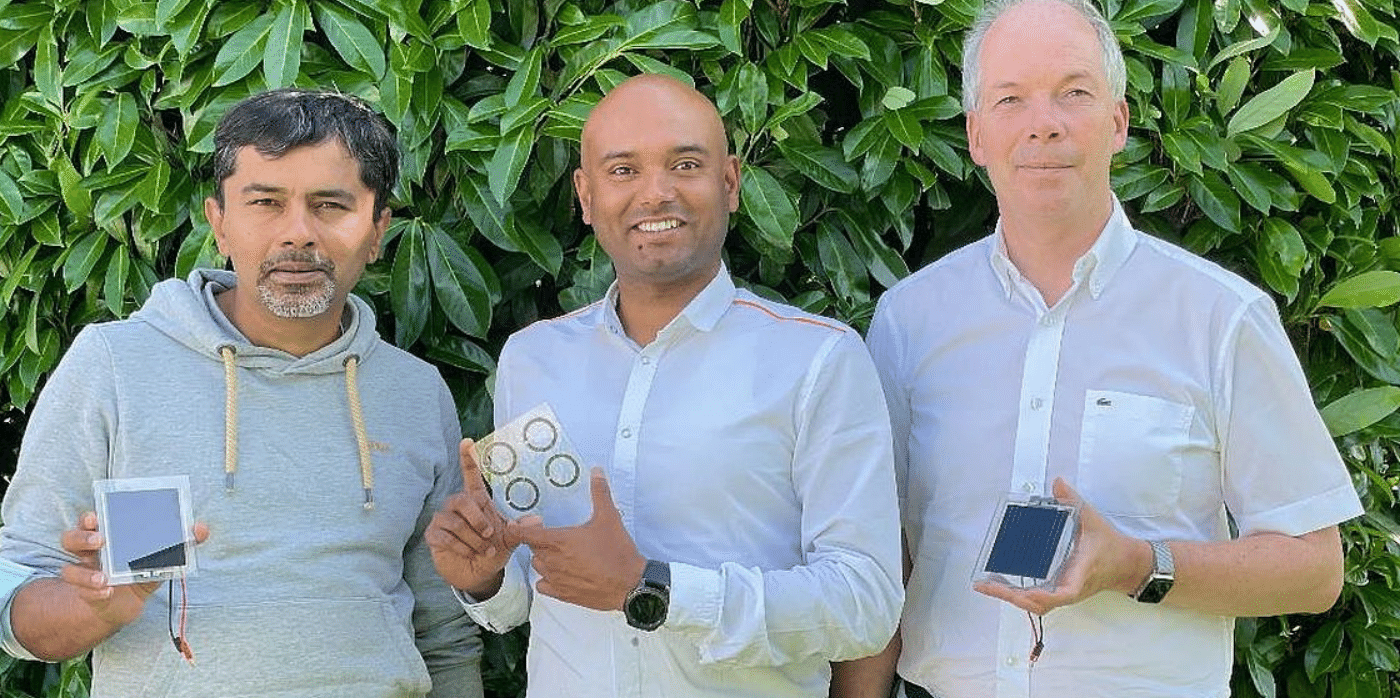

Ubiquitous Energy has completed a number of demonstration projects, including at Michigan State University and at the Boulder Commons apartment community in Colorado.

The company plans to open its first factories producing floor-to-ceiling solar windows in 2024. It also hopes to grow its partnerships, which have so far included window companies Asahi, Pilkington and Andersen.

Past aesthetic solutions to the issue of intrusive solar panels have come from designer Marjan van Aubel, who created colourful skylights reminiscent of stained glass, and Tesla, which released camouflaged Solar Roof tiles.

Architects have also been creatively integrating the technology into buildings, with designs such as BIG and Heatherwick Studio’s “dragonscale solar skin” on the roof of Google’s Bay View campus in Silicon Valley and Shigeru Ban’s sail-like moving wall of photovoltaics at La Seine Musical near Paris.

All images are courtesy of Ubiquitous Energy.

Solar Revolution

This article is part of Dezeen’s Solar Revolution series, which explores the varied and exciting possible uses of solar energy and how humans can fully harness the incredible power of the sun.