New Year, New You? 8 Inspirational Resolutions for Architects in 2024

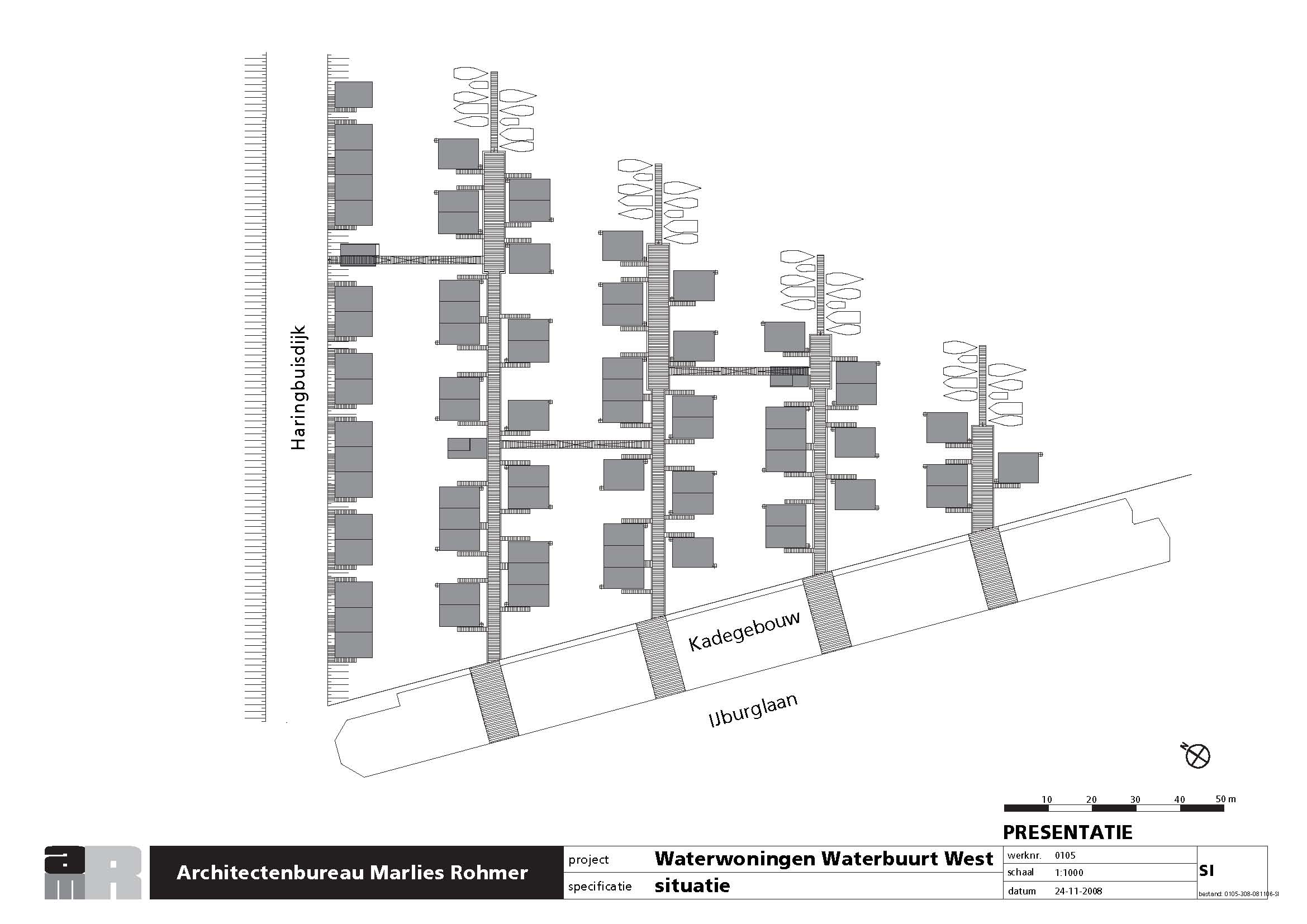

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

The story of the New Year’s resolution began over 4,000 years ago in ancient Babylon. From what we know, at the end of each year, the pious and virtuous, polytheistic Babylonians made promises to their various gods, pledging to settle outstanding debts and return any borrowed goods. It was their way of starting the coming year on a right and moral footing.

Our reasoning for making resolutions might not be as serious as returning your neighbor’s grain barrel before you curse your crops for the rest of the year; however, four millennia later, the purpose remains true. Bringing in the new year always feels like the right time to cast off old habits, reset and wipe the slate clean as best we can — I’m pretty sure the Babylonians could have related to that phrase, actually.

New Year, new you? Well, no, probably not. New Year, a slightly improved you? We can get on board with that one. So, recognizing that we are not Bablyonians and that resolutions no longer need to be life or death, Architizer has outlined eight manageable resolutions that employ minor changes that will hopefully inspire you to make the most of 2024. They might even make you a better architect if you’re lucky.

Read more.

Robarts Library Reading Room by Superkül, Toronto, Canada Photograph by doublespace photography inc. Jury Award Winner, 11th Annual A+Awards, Institutional, Educational Interiors

Of course, you cry with a big eye roll at the lack of inventiveness. Wait —hear me out. Don’t close your tab just yet. There’s a reason “read more” is one of the most common resolutions people make. It’s because we never, ever, stick to it. We all read so much every day, but unfortunately, I don’t think Instagram captions and TikTok text overlays count. So here we are again: “2024 — Read more” (you can’t deny it’s got a ring to it).

We all know knowledge is the key and all that, so this year, why not try a different approach; what about starting or joining a book club? You could even focus it on architectural books if you wanted to double down. You could switch it up, a technical, a historical, and then a fictional, to stop things from getting too repetitive. You could choose to host it at your local library; they really need support, and they were literally made for book clubs, so it’s a win-win. What’s more, it’s my understanding that book clubs have biscuits, so what’s not to love, really?

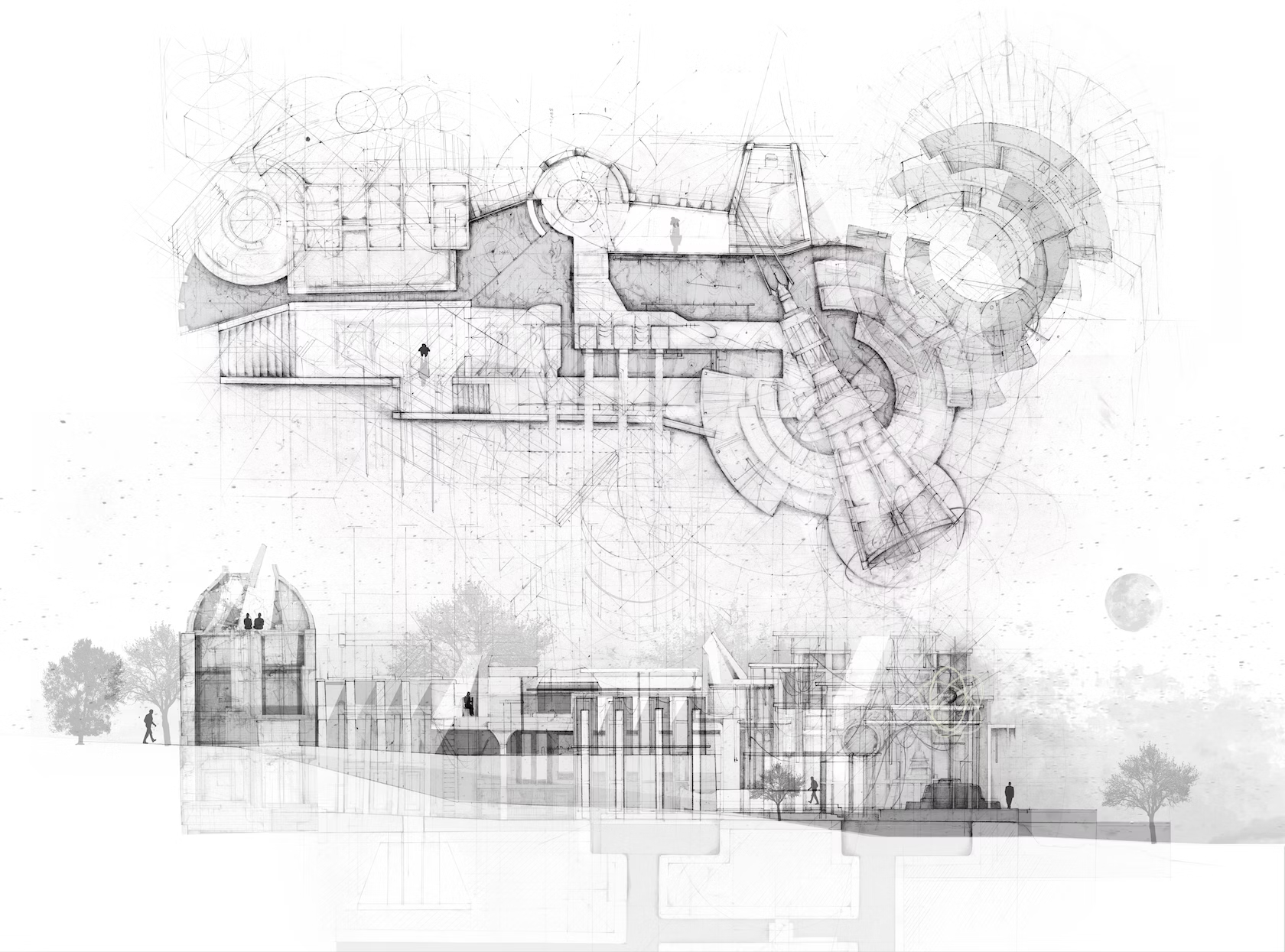

Draw more.

The Last Resort by Nikhita Sivakumar, Student Winner, A+Vision Awards 2023, Drawing, Hand Drawn Drawing.

This is one for the people whose sketches look more like Minecraft models than multi-lined masterpieces.

Sketching is a skill; yes, some people are naturally good at it, others not so much. But skills can be learned, and that means practice. So, if you want to improve your illustration, sharpen your shading, and hone your hatching, make it your mission to fill an entire sketchbook by the end of the year with spontaneous architectural doodles, ideas and musings.

Or if carting around a sketchbook all day every day feels a little too “Renaissance painter trying to find a muse” for this century, why not sketch your ideas on anything but traditional paper? Napkins, walls, banana peels — get creative with your mediums. Collect them all up, and at the end of the year, you’ll have a unique timeline of precious “junk” that tracks your progress.

Both are a great way to keep the creative juices flowing daily, and who’s to know, we might even be looking at the next Le Corbusier (probably not, but it’s important to dream).

See more.

Francisco Tirado – Cobe Architects, Studio Winner, A+Vision Awards 2023, Best Of The Year, Architectural Photographer Of The Year

There’s a Bart Simpson-esque joke in there somewhere, but let’s keep it professional…

Honestly, seeing more doesn’t always mean spending lots of money, booking lots of trips, and traveling around the world — as much fun as that can be. Seeing more can also mean taking notice of your immediate surroundings. We are almost all somewhere someone else wants to visit. So, be a tourist in your own town. Wander, explore and uncover the story of the architecture around you. Or, if you’re a fan of a plan, you could take it one step further and make a list of buildings you haven’t seen yet, or you’d like to see again and map out a route to visit them.

Explore where you are, and while you are at it, you can develop your photography skills by challenging yourself to take at least one photo a week of a building, a material or architectural detail that inspires you. By the end of the year, you’ll have fifty-two images that are a timeline of 2024.

You never know. You might even take a photograph that wins Architizer’s 2024 A+Awards.

Find Inspiration.

Finding new ways to be inspired is a year-round challenge. So, how about setting yourself a resolution that will give you the creative boost you need this year?

You could pick a country, one for each of the twelve months of the year, and commit to learning about its architectural heritage, its most recognized style, or its most well-known architect. You can find some great examples in Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture. By the end of 2024, you’ll have a knowledge of global architecture that could rival anyone in the office, and I bet you’ll be surprised at how much more diverse and exciting your projects become after just a few months.

Or if international architecture seems like too broad and overwhelming before you’ve even begun (this is always a pitfall with resolutions. They should be something you could actually achieve), why not work your way through the alphabet instead? A for Atrium, B for Balcony, C for Columns and so on? It’s a quick and easy approach to expanding your design horizons, and the topics can be as broad or as specific as you choose.

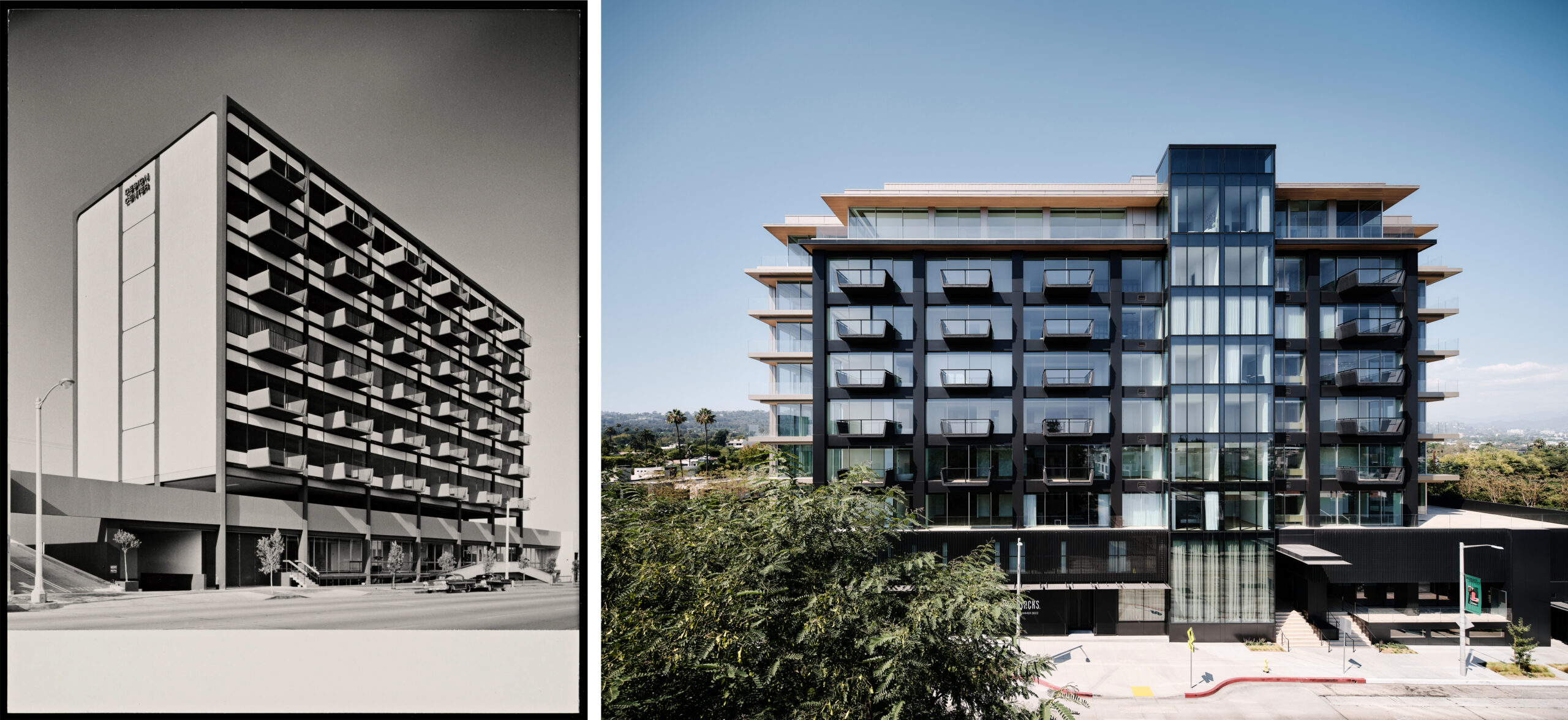

Go Green.

Eucalyptus Society Garden by SWA GROUP / Los Angeles, Guangzhou, China. Popular Choice Winner, 11th Annual A+Awards, Public Parks & Green Spaces

I think it is safe to assume this one is on pretty much every architect’s list for 2024. Be more eco-conscious, be less wasteful and design smarter for the planet and its people. However, you frame it —this one is a biggie. Oh, but what to do? How about pledging to incorporate at least one additional sustainable design element in every project? This could range from using a recycled material to adding an innovative energy-saving product. But the catch is that it has to be one you added above and beyond your initial proposal; that way, you’re boosting your impact. Start with one and see how many you can add.

Or, if you’re the type of person who responds better to financial penalties, what about implementing a personal swear jar? Instead of being penalized for cursing, you need to cough up every time you specify using non-sustainable material. It’s a great way to keep yourself accountable for your choice, and at the end of the year, you can donate the cash to a worthy cause.

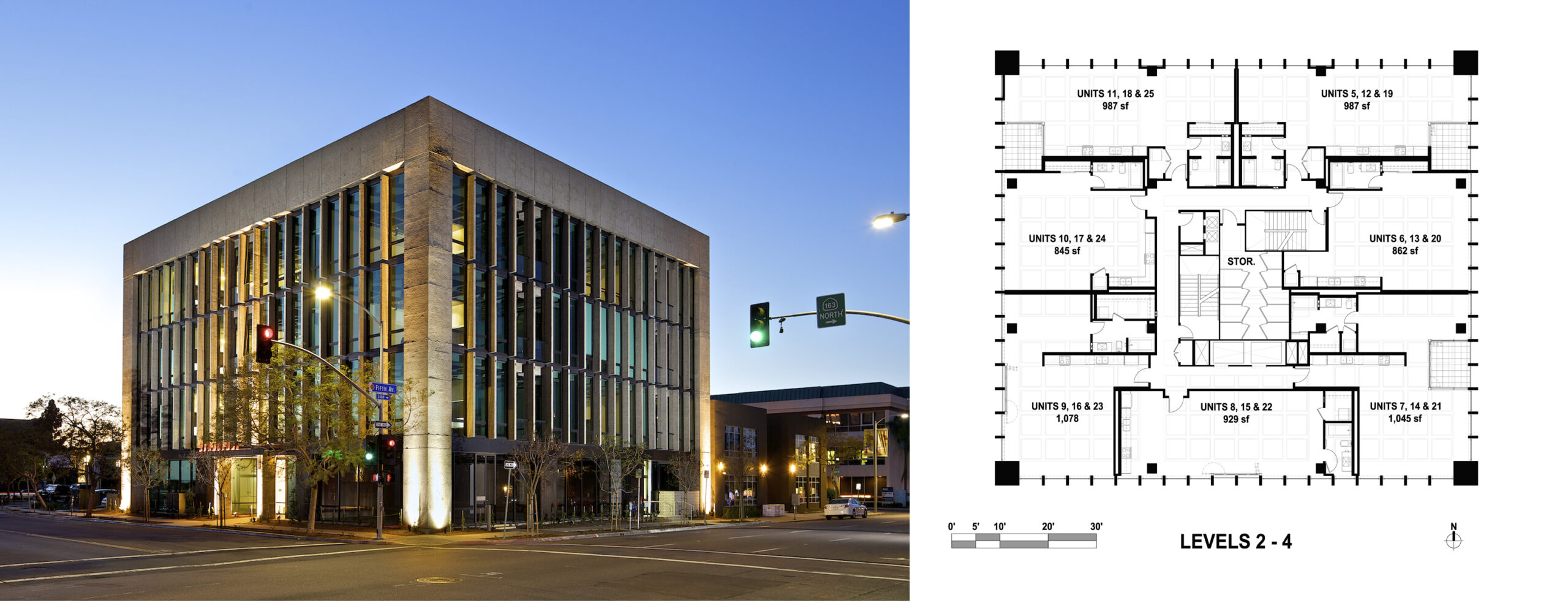

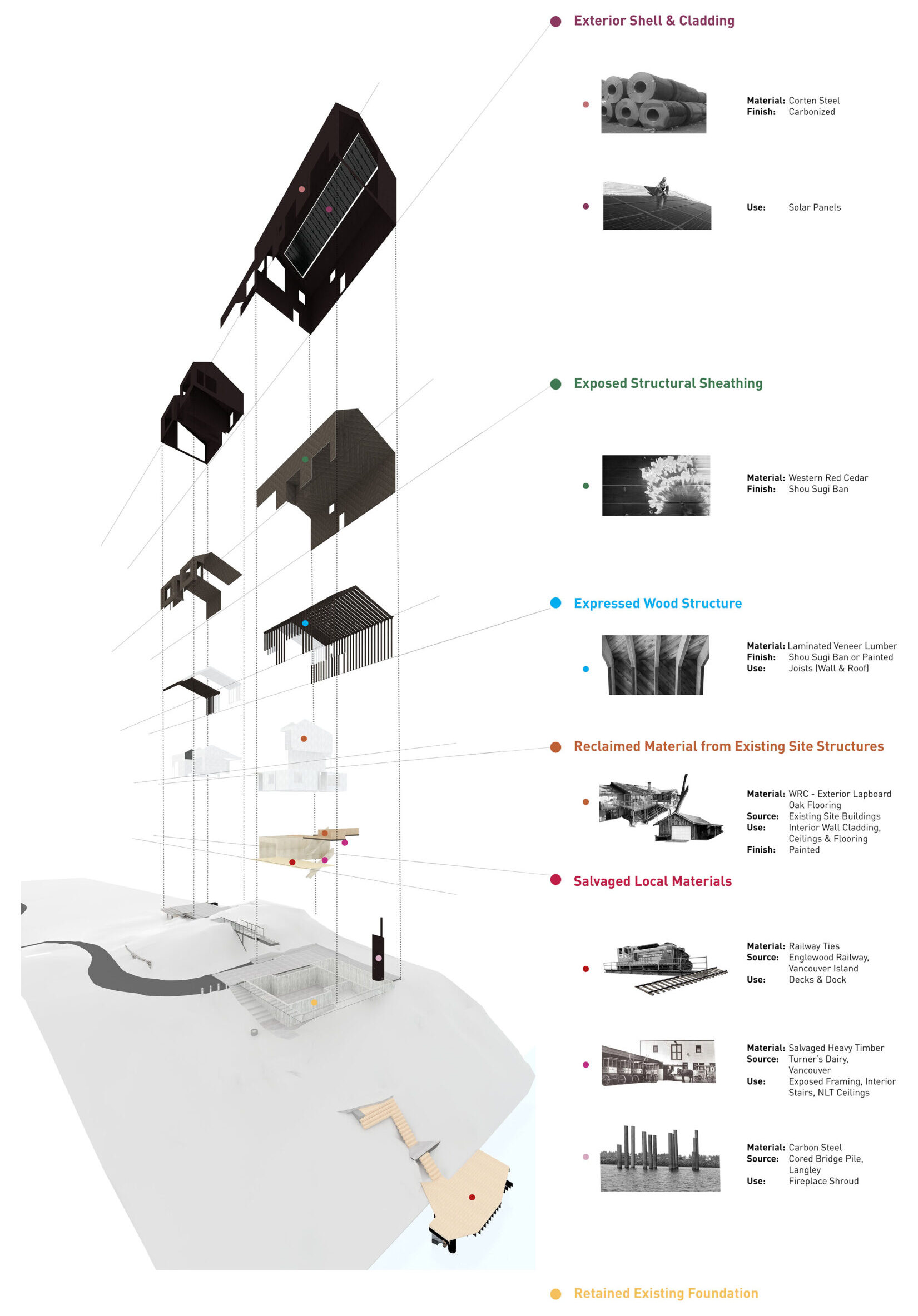

Prepare for the future.

Silk & Stone by Mohammad Qasim Iqbal. Student Winner, A+Vision Awards 2023, Visualization, Ai Assisted Visualization.

The future is here, and there is no denying it. AI, VR, and all the other acronyms you can think of are here to stay. So, this year, your resolution could help you prepare and keep you at the forefront of the monumental changes we are witnessing.

Get going with virtual reality. Whether it’s using VR for client presentations or exploring virtual construction, stop messing with the 2D and get yourself involved in the virtual world. Not only will you have a blast messing about in your models, but your clients will also thank you for making understanding space planning so much easier.

Or get ahead of the game in AI. If you still need to, resolve to learn what it is and how it’s going to help you as an architect. You can make it your mission to listen to every episode of Evelyn Lee’s Practice of Architecture podcast, or you can sign up for something like wordsmith Nikita Morell’s ChatGPT for Architects Masterclass.

You could even stick your alerts on for LinkedIn posts from our very own Editor-in-Chief Paul Keskeys and read the reviews on Architizer Tech to get updates on the latest applications, innovations and tips that will keep you up to date on what’s hot and what not in the tech-o-sphere. (we think you should do this either way).

Rein it in.

As architects and designers were often told, our industry is complicated, exclusive and inaccessible. And in some cases, they would be right. So, this year, why not simplify things? Ditch the dialogue. Challenge yourself to stop using architectural jargon, be direct and to the point and say exactly what you mean. At the end of the day, you might find it improves your business when people actually understand what you are talking about.

Or if thats not your problem, what about committing to downscaling overly ambitious ideas? We often get carried away, going smidge overboard every now and again. In all fairness, it’s often part of the fun. I do not deny there is a time and place for glass columns and gold-plated beams, but how about, if you find you’re one of those architects who spends more time scaling back than scaling up, that this year you challenge yourself to rein it in and refocus your precious time on to yourself instead of arguing the necessity of triple height ceilings in the guest bathroom that no one asked for?

Banish the beige.

GRiD by Spark Architects, Singapore. Jury Award Winner, 11th Annual A+Awards, Retail. Photographs by Fabian Ong.

Or, if your thinking, “count me out of reining it in,” then it’s time to toss out the tepid and embrace the bold. Beige isn’t just a color; it’s a symbol of safe choices that lull us into a creative slumber. This year you could set yourself the task of shake off that drowsiness and give your work some much-needed pizzazz.

Think about it. When was the last time you stepped out of our comfort zone with color? I’m not talking about a touch of terracotta or a splash of sage. I’m talking full kaleidoscope. It’s not just about painting the town red (or green, or purple). Let’s get inventive with our spaces have a heart-to-heart with our materials. This year could be a great time to experiment and give your designs the innovative eye they deserve.

And who knows, those eye catching hues it might just be what makes them stand out to our jurors in future A+Awards competitions.

Celebrate the wins.

And finally, and in my opinion, most importantly, celebrate the wins! We said that the new year is all about reflecting and looking back at our achievements, recognizing what we did well or not so well. But why wait? Why not celebrate the wins as and when they happen? Commit yourself to taking time out, whether it’s a day, an hour or a week, to really appreciate the times that things went well. Don’t just move on to the next challenge and forget to take time to pat yourself and your team on the back and say, “Well done!”

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.