Egg Chair would not be designed today say Luke Pearson and Tom Lloyd

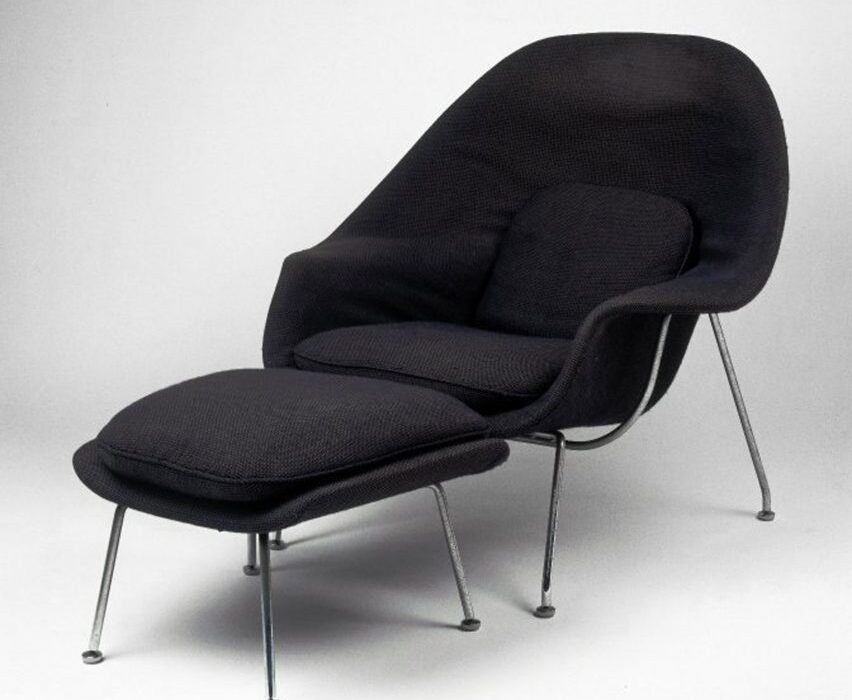

Concave chairs like Arne Jacobsen’s Egg and Eero Saarinen’s Womb don’t meet today’s definition of good design, according to the founders of design studio Pearson Lloyd.

Luke Pearson and Tom Lloyd said furniture with glued upholstery no longer makes sense because it is too difficult to recycle.

They argue that mid-century designs like the Egg and Womb, which require a large amount of glue to achieve their concave shapes, are no longer appropriate for production.

“People still hold up the Egg chair as an icon of design, even though it’s made of textile glued onto foam and moulded onto metal, making it almost impossible to repair or recycle,” Lloyd told Dezeen.

“Any textile which is a concave surface is not fit for purpose any more,” he said.

Shift to “planet-first approach”

In a joint statement sent exclusively to Dezeen, titled “Why the Egg chair would not be designed today”, the Pearson Lloyd founders said that today’s furniture must embrace the circular economy.

They said the definition of “good design” must now consider environmental impact.

“We are no longer able to judge the quality of a design by aesthetics alone,” they said.

“The value proposition of design is shifting rapidly towards a planet-first approach, and it is leading us to question how we behave and what we make. If a design doesn’t minimise carbon and maximise circularity, is it good?”

Finnish architect Eero Saarinen developed the Womb chair in 1946. It went into production for furniture brand Knoll two years later.

Danish architect Arne Jacobsen designed the Egg chair, as well as the smaller Swan chair, in 1958 for the interior of the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen. They were marketed by Danish brand Fritz Hansen soon after and have been in continuous production ever since.

“Almost impossible” to recycle

All three designs are produced by glueing leather or textile onto polyurethane foam, then moulding it over a structural frame of metal or fibreglass.

This results in products that are easy to manufacture and highly lightweight, but it also makes them harder to recycle and consequently increases their ecological footprint.

This technology was revolutionary in the mid-20th century, but Pearson and Lloyd believe it has since become defunct, due to “the poor environmental credentials of this material stack”.

“Today we are questioning whether 20th-century technologies are appropriate, to eliminate products that have a short and single carbon lifecycle,” they said.

The pair reject the counterargument that, as design classics, these products often outlive their expected lifespans.

“What about the generations of derivative products whose useful life is so much shorter?” they said. “They have been incinerated or added to landfill.”

Pearson Lloyd now avoids glued textiles

Pearson Lloyd has previously used glued textiles in its own designs. But it now avoids them as much as possible, said the founders.

They instead promote the use of linear or convex shapes, which allow textiles to be held in place with drawstrings rather than glue.

Recent launches such as the CoLab classroom furniture, produced by British brand Senator, demonstrate this approach.

Pearson and Lloyd believe that new technologies such as 3D knitting also offer viable alternatives.

“We are excited by new material innovations such as 3D knitting that are allowing us to explore new design paradigms, new aesthetics and new demountable structures, to reflect the times we live in and our new priorities,” added the duo.

Read the full statement below:

Why the Egg chair would not be designed today

Egg, Swan, Womb: these organic words are resonant of nature. They are also names of some of the most recognisable chairs of the 20th century that reimagined seating in bold forms. This new aesthetic language of complex compound forms was enabled by technological developments in polyurethane foam moulding, glues, and fibreglass. These icons of design have been held up as benchmarks to which designers the world over should aspire.

Today, our definition of good design is changing. We are no longer able to judge the quality of a design by aesthetics alone. The value proposition of design is shifting rapidly towards a planet-first approach, and it is leading us to question how we behave and what we make. If a design doesn’t minimise carbon and maximise circularity is it good?

So a question we have been asking ourselves recently as we have been avoiding glueing textiles: would iconic products like the Swan, Egg and Womb chairs be designed today?

Circular design demands that products can be repaired to extend their life and recycled at end-of-life, so that carbon can be recovered by returning constituent materials to their discrete technical cycles. The vision is that we could use the products and materials in circulation today to cater to our needs in the future, preventing the extraction of raw materials.

Icons such as the Egg, Swan and Womb chair apply textiles to concave padded surfaces for comfort. This requires the textile to be glued onto foam to hold it in place. The foam is then moulded over a structural frame or surface, connecting three materials together in a way that is almost impossible to separate for repair or recycling. The poor environmental credentials of this material stack have led to the Egg aesthetic disappearing from contemporary design.

Now, ironically, in the case of these iconic chairs, their cultural durability means that they are cherished way beyond their normal and expected lifespans and, like classic cars, through careful restoration, they may indeed last forever. But what about the generations of derivative products whose useful life is so much shorter? They have been incinerated or added to landfill.

Today we are questioning whether 20th-century technologies are appropriate, to eliminate products that have a short and single carbon lifecycle. We are excited by new material innovations such as 3D knitting that are allowing us to explore new design paradigms, new aesthetics and new demountable structures, to reflect the times we live in and our new priorities.

Main image is courtesy of Shutterstock.