The Unsung Success Story of Increased Efficiency (And Why We All Need More of It)

A number of organizations have charted a path to a decarbonized world by 2050 and broken down required action in four areas or “pathways.” The third pathway is often the unsung hero of our climate successes to date: efficiency.

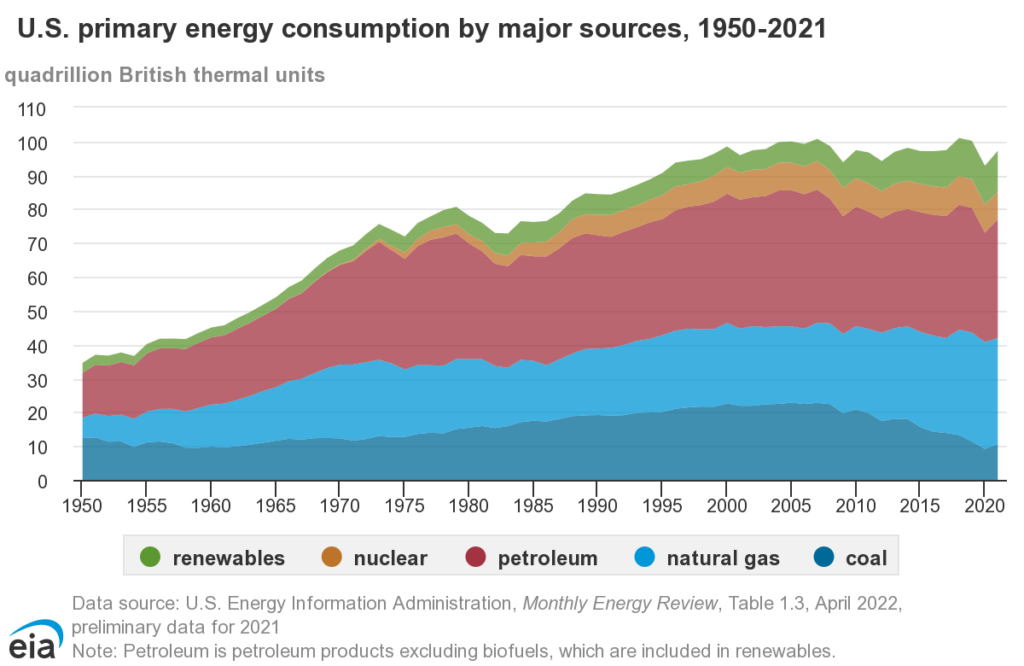

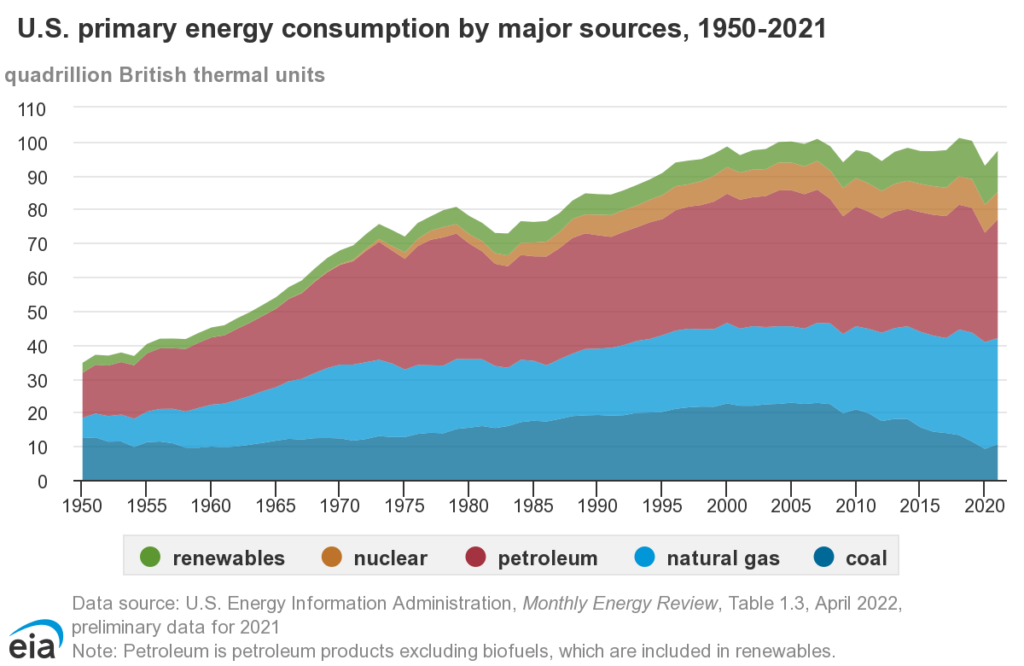

Simply put, efficiency means using less of a resource to achieve the same result. The 1970s oil embargo and energy crisis inspired the modern energy efficiency movement in the United States, which led to a $360 billion energy efficiency industry. This industry managed to keep both energy and electricity usage flat over the past 20 years, despite the fact that the population has grown by 10% from 301 million to 331 million over the same period.

According to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, over a 25 year period from 1980 to 2014, efficiency investments resulted in a 50% improvement in US energy intensity. This means that while energy use increased by 26%, overall gross domestic product (GDP) far outpaced energy use, increasing by 149%.

These decades of unsung progress have significantly reduced energy use in buildings, industry, and transportation and thus lowered demand for more fossil fueled power. Amidst the doom and gloom of the climate crisis, it’s important to remember to celebrate and amplify what we humans are doing right. Efficiency falls on the bright side of the “best of times, worst of times” dichotomy, so let’s make sure to give ourselves credit for our successes.

We might call efficiency the low hanging fruit on the pathway to decarbonization. There’s so much more to be picked.

Efficiency sometimes gets a bad rap because it so often includes messages of scarcity like “reduce” and “limit,” and can feel like doing less bad rather than more good. This narrative suggests that people have to sacrifice or change their lifestyle, which few of us want to hear. But this is largely a communication problem.

Amazing advances in technology mean that our homes and vehicles can use less energy without anyone noticing, and without sacrificing our quality of life. For example, refrigerators use 75% less energy now than they did a couple decades ago, and they perform better and cost less. Light bulbs have followed the same trend, accounting for 10% of an average home’s electricity consumption in 2015 and only 4% in 2021, thanks to LEDs. A decarbonized life has many advantages and thus offers a narrative of abundance rather than scarcity. Denmark uses about 40% of the energy that the US uses and yet it’s recognized for the second highest quality of life in the world.

Taking efficiency to the next level

While we celebrate all these society-wide gains in efficiency, in our family we find it easy to take efficiency to the next level. We believe the climate crisis asks this of us. For us, being efficient and wasting less involves both:

- Technologies—the products, appliances and fixtures in our home that reduce energy use through their operations. Think efficient appliances, insulation, LED lighting, etc. (shower heads are a personal favorite), along with what we call the “big moves” of heat pumps for space and water heating, which cut home energy use by a whopping 50% to 75%.

- Behaviors—the routines, habits, and practices we form that have a measurable impact on carbon reduction. Think hang-drying laundry and eating less meat.

Combining both strategies will supercharge energy savings and make it easier for utilities, or rooftop solar panels, to provide all the clean power our household needs.

But it’s also clear that efficiency isn’t a silver bullet, and we can’t collectively “efficiency our way out” of the climate crisis. Many of the efficiency solutions of recent decades included enhanced methane and petroleum burning technologies, but no matter how efficient your gas furnace or gas car is, it’s still burning fossil fuels that emit the greenhouse gases that are changing the climate. This is why efficiency and the electrification pathway go hand in hand. It’s much easier to electrify everything and run our lives on clean electricity if we first reduce our energy needs.

At the same time, while some proponents of electrification believe we can decarbonize without worrying much about efficiency, a commitment to efficiency is undoubtedly the best way to make electrification work. Efficiency lowers how much new renewable electricity we’ll need in the coming decades.

Household efficiency strategies

Our family’s efficiency strategies (which mostly now feel old school) include blowing in extra cellulose insulation into our attic, to increase home comfort, and air sealing all the penetrations so conditioned air doesn’t sneak out. Other strategies include installing low-flow shower heads and faucet aerators to reduce both water use and the energy needed to heat the water.

Over the past decade, we also replaced most of our old appliances with ENERGY STAR–certified, all-electric, super-efficient ones, and opted for heat pumps to heat our home and water and to dry our clothes, because heat pumps are the most efficient way to create heat. We also practice easy passive cooling techniques during our increasingly hot summers, which most of the time means we don’t need air-conditioning. Finally, we bought our home in a neighborhood with a high walk score so that we can move efficiently and walk, bike, and ride transit whenever possible. All these efficiency measures make it easier for our family’s 28 solar panels to meet most of our home and transportation energy needs.

All in all, efficiency is a crucial pathway to both personal and societal decarbonization. And whether you sing it’s praises or not, we’ve all gotten a lot more efficient in how we use energy over the past decades. It’s time to build on this success and continue to find ways to use electric, renewable energy better.

This article is part of a series by Naomi Cole and Joe Wachunas, first published in CleanTechnica. Through “Decarbonize Your Life,” they share their experience, lessons learned, and recommendations for how to reduce household emissions, building a decarbonization roadmap for individuals.

The authors:

Meanwhile, the Xiaoyunlu 8, MAHA Residential Park project by Ballistic Architecture Machine in Beijing, another A+Award popular winner this year, weaves together disparate sections of the site of various eras and styles into one seamless and soothing green space. Residents can now fully access and enjoy the park’s gardens, historical sites and communal areas.

Meanwhile, the Xiaoyunlu 8, MAHA Residential Park project by Ballistic Architecture Machine in Beijing, another A+Award popular winner this year, weaves together disparate sections of the site of various eras and styles into one seamless and soothing green space. Residents can now fully access and enjoy the park’s gardens, historical sites and communal areas. These projects are a mere snapshot of why at Architizer, we believe that landscapers are the unsung heroes of the design world. It’s why this week we are highlighting jobs in the sector.

These projects are a mere snapshot of why at Architizer, we believe that landscapers are the unsung heroes of the design world. It’s why this week we are highlighting jobs in the sector.